Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anti-Zionism and Antisemitism Cosmopolitan Reflections

Anti-Zionism and Antisemitism Cosmopolitan Reflections David Hirsh Department of Sociology, Goldsmiths, University of London, New Cross, London SE14 6NW, UK The Working Papers Series is intended to initiate discussion, debate and discourse on a wide variety of issues as it pertains to the analysis of antisemitism, and to further the study of this subject matter. Please feel free to submit papers to the ISGAP working paper series. Contact the ISGAP Coordinator or the Editor of the Working Paper Series, Charles Asher Small. Working Paper Hirsh 2007 ISSN: 1940-610X © Institute for the Study of Global Antisemitism and Policy ISGAP 165 East 56th Street, Second floor New York, NY 10022 United States Office Telephone: 212-230-1840 www.isgap.org ABSTRACT This paper aims to disentangle the difficult relationship between anti-Zionism and antisemitism. On one side, antisemitism appears as a pressing contemporary problem, intimately connected to an intensification of hostility to Israel. Opposing accounts downplay the fact of antisemitism and tend to treat the charge as an instrumental attempt to de-legitimize criticism of Israel. I address the central relationship both conceptually and through a number of empirical case studies which lie in the disputed territory between criticism and demonization. The paper focuses on current debates in the British public sphere and in particular on the campaign to boycott Israeli academia. Sociologically the paper seeks to develop a cosmopolitan framework to confront the methodological nationalism of both Zionism and anti-Zionism. It does not assume that exaggerated hostility to Israel is caused by underlying antisemitism but it explores the possibility that antisemitism may be an effect even of some antiracist forms of anti- Zionism. -

A Survey of Textbooks Most Commonly Used to Teach the Arab-Israeli

A Critical Survey of Textbooks on the Arab-Israeli and Israeli-Palestinian Conflict Working Paper No. 1 │ April 2017 Uzi Rabi Chelsi Mueller MDC Working Paper Series The views expressed in the MDC Working Paper Series are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the Moshe Dayan Center for Middle Eastern and African Studies or Tel Aviv University. MDC Working Papers have not undergone formal review and approval. They are circulated for discussion purposes only. Their contents should be considered preliminary and are not to be reproduced without the authors' permission. Please address comments and inquiries about the series to: Dr. Chelsi Mueller Research Fellow The MDC for Middle Eastern and African Studies Tel Aviv University Ramat Aviv, 6997801 Israel Email: [email protected] Tel: +972-3-640-9100 US: +1-617-787-7131 Fax: +972-3-641-5802 MDC Working Paper Series Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank the research assistants and interns who have contributed significantly to this research project. Eline Rosenhart was with the project from the beginning to end, cataloging syllabi, constructing charts, reading each text from cover to cover, making meticulous notes, transcribing meetings and providing invaluable editorial assistance. Rebekka Windus was a critical eye and dedicated consultant during the year-long reading phase of the project. Natasha Spreadborough provided critical comments and suggestions that were very instrumental during the reading phase of this project. Ben Mendales, the MDC’s project management specialist, was exceptionally receptive to the needs of the team and provided vital logistical support. Last but not least, we are deeply grateful to Prof. -

Aliyah and Settlement Process?

Jewish Women in Pre-State Israel HBI SERIES ON JEWISH WOMEN Shulamit Reinharz, General Editor Joyce Antler, Associate Editor Sylvia Barack Fishman, Associate Editor The HBI Series on Jewish Women, created by the Hadassah-Brandeis Institute, pub- lishes a wide range of books by and about Jewish women in diverse contexts and time periods. Of interest to scholars and the educated public, the HBI Series on Jewish Women fills major gaps in Jewish Studies and in Women and Gender Studies as well as their intersection. For the complete list of books that are available in this series, please see www.upne.com and www.upne.com/series/BSJW.html. Ruth Kark, Margalit Shilo, and Galit Hasan-Rokem, editors, Jewish Women in Pre-State Israel: Life History, Politics, and Culture Tova Hartman, Feminism Encounters Traditional Judaism: Resistance and Accommodation Anne Lapidus Lerner, Eternally Eve: Images of Eve in the Hebrew Bible, Midrash, and Modern Jewish Poetry Margalit Shilo, Princess or Prisoner? Jewish Women in Jerusalem, 1840–1914 Marcia Falk, translator, The Song of Songs: Love Lyrics from the Bible Sylvia Barack Fishman, Double or Nothing? Jewish Families and Mixed Marriage Avraham Grossman, Pious and Rebellious: Jewish Women in Medieval Europe Iris Parush, Reading Jewish Women: Marginality and Modernization in Nineteenth-Century Eastern European Jewish Society Shulamit Reinharz and Mark A. Raider, editors, American Jewish Women and the Zionist Enterprise Tamar Ross, Expanding the Palace of Torah: Orthodoxy and Feminism Farideh Goldin, Wedding Song: Memoirs of an Iranian Jewish Woman Elizabeth Wyner Mark, editor, The Covenant of Circumcision: New Perspectives on an Ancient Jewish Rite Rochelle L. -

Israeli History

1 Ron’s Web Site • North Shore Flashpoints • http://northshoreflashpoints.blogspot.com/ 2 • http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wb6IiSUx pgw 3 British Mandate 1920 4 British Mandate Adjustment Transjordan Seperation-1923 5 Peel Commission Map 1937 6 British Mandate 1920 7 British Mandate Adjustment Transjordan Seperation-1923 8 9 10 • Israel after 1973 (Yom Kippur War) 11 Israel 1982 12 2005 Gaza 2005 West Bank 13 Questions & Issues • What is Zionism? • History of Zionism. • Zionism today • Different Types of Zionism • Pros & Cons of Zionism • Should Israel have been set up as a Jewish State or a Secular State • Would Israel have been created if no Holocaust? 14 Definition • Jewish Nationalism • Land of Israel • Jewish Identity • Opposes Assimilation • Majority in Jewish Nation Israel • Liberation from antisemetic discrimination and persecution that has occurred in diaspora 15 History • 16th Century, Joseph Nasi Portuguese Jews to Tiberias • 17th Century Sabbati Zebi – Declared himself Messiah – Gaza Settlement – Converted to Islam • 1860 Sir Moses Montefiore • 1882-First Aliyah, BILU Group – From Russia – Due to pogroms 16 Initial Reform Jewish Rejection • 1845- Germany-deleted all prayers for a return to Zion • 1869- Philadelphia • 1885- Pittsburgh "we consider ourselves no longer a nation, but a religious community; and we therefore expect neither a return to Palestine, nor a sacrificial worship under the sons of Aaron, nor the restoration of any of the laws concerning a Jewish state". 17 Theodore Herzl 18 Theodore Herzl 1860-1904 • Born in Pest, Hungary • Atheist, contempt for Judaism • Family moves to Vienna,1878 • Law student then Journalist • Paris correspondent for Neue Freie Presse 19 "The Traitor" Degradation of Alfred Dreyfus, 5th January 1895. -

Hebrew 2241 SP17.Pdf

Attention! This is a representative syllabus. The syllabus for the course you are enrolled in will likely be different. Please refer to your instructor’s syllabus for more information on specific requirements for a given semester. HEBREW 2241/JEWSH ST 2242 THE CULTURE OF CONTEMPORARY ISRAEL Instructor: Office hours: Office: E-mail: OBJECTIVES: The purpose of this course is to familiarize students with contemporary Israeli culture in all of its diversity. Since the founding of the State in 1948, Israeli society has faced a series of dramatic challenges and has undergone tremendous changes. This course will survey the major social, cultural, religious and political trends in Israel, with special emphasis on the post-1967 period. We will explore developments in music, dance, poetry, and archaeology; responses to founding ideals and ideologies; the impact of the Arab-Israeli conflict; efforts to absorb new waves of immigration and to deal with questions of ethnicity; and the roles of religion and secularism in Israeli society. We will draw on a broad range of material, including print media, films, and YouTube clips. By the end of the course, students should have an insight into the complexity of Israeli society and the richness of Israeli culture, as well as an understanding of Israel’s role in Jewish life, the Middle East, and the world at large. COURSE REQUIREMENTS: ATTENDANCE AND PARTICIPATION (10%): 1. You are expected to attend all class sessions. 2. You are expected to read all assigned material. 3. You should be prepared to participate in class discussions of assigned readings and videos shown in class. -

Jewish State and Jewish Land Program Written in Jerusalem by Yonatan Glaser, UAHC Shaliach, 2003

December 2003 \ Kislev 5764 Jewish State and Jewish Land Program written in Jerusalem by Yonatan Glaser, UAHC Shaliach, 2003 Rationale We live in a time where taking an interest in Israel is not taken for granted and where supporting Israel, certainly in parts of our public life like on campus, may be done at a price. Even in the best of times, it is important to be conceptually clear why we Jews want our own country. What can and should it mean to us, how might it enrich and sustain us – those of us who live in it and those of us who do not? What might contributing to its well-being entail? If that is at the best of times, then this – one of the most difficult times in recent memory – is an excellent time to re- visit the basic ideas and issues connected to the existence of Israel as a Jewish state in the ancient Land of Israel. With this in mind, this program takes us on a ‘back to basics’ tour of Israel as a Jewish country in the Jewish Land. Objectives 1. To explore the idea of Jewish political independence. 2. To explore the meaning of Jewish historical connection to Eretz Yisrael 3. To learn about the Uganda Plan in order to recognize that issues connected to independence and living in Eretz Yisrael have been alive and relevant for at least the last 100 years. Time 1 hour and fifteen minutes Materials 1. Copies of the four options (Attachment #1) 2. White Board or poster Board. -

Israeli Music and Its Study

Music in Israel at Sixty: Processes and Experiences1 Edwin Seroussi (Hebrew University of Jerusalem) Drawing a panoramic assessment of a field of culture that resists clear categorizations and whose readings offer multiple and utterly contrasting options such as Israeli music is a challenge entailing high intellectual risks. For no matter which way your interpretations lean you will always be suspected of aligning with one ideological agenda or another. Untangling the music, and for that matter any field of modern Israeli culture, is a task bound to oversimplification unless one abandons all aspirations to interpret the whole and just focuses on the more humble mission of selecting a few decisive moments which illuminate trends and processes within that whole. Modest perhaps as an interpretative strategy, by concentrating on discrete time, spatial and discursive units (a concert, a band, an album, an obituary, a music store, an academic conference, etc) this paper attempts to draw some meaningful insights as sixty years of music-making in Israel are marked. The periodic marking of the completion of time cycles, such as decades or centuries, is a way for human beings to domesticate and structure the unstoppable stream of consciousness that we call time.2 If one accepts the premise that the specific timing of any given time cycle is pure convention, one may cynically interpret the unusually lavish celebrations of “Israel at Sixty” as a design of Israeli politicians to focus the public attention both within and outside the country on a positive image of the state 1 This paper was read as the keynote address for the conference Hearing Israel: Music, Culture and History at 60, held at the University of Virginia, April 13-14, 2008. -

Bbgn Iyar 06 Final

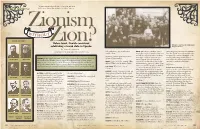

“As long as deep in the heart the soul of a Jew yearns, and toward HOLIDAY the East an eye looks to Zion, our hope is not yet lost.” HATIKVAH Zionism WITHOUT CHARACTERS: Zion?Before Israel, Zionists considered Delegates convene at the Sixth Zionist establishing a Jewish state–in Uganda. Congress in 1903. ISRAEL GPO By Yaffa Klugerman SPECIAL THANKS TO TZVI KLUGERMAN FOR HIS HELP WITH THIS PLAY and gentlemen, I give you the next HERZL: Of course in Palestine. This is great European power—for the first time Jewish colony. merely the first step. Uganda is not Zion since the destruction of the Temple—has and will never be Zion. This is nothing recognized the national demands of the (Removes cover to reveal map of East more than a relief measure. We can Jewish people. But I’m sorry that we ISRAEL GPO ISRAEL GPO SETTING: A large conference room. To the right, a podium faces numerous chairs on Africa. All gasp loudly.) Theodor Herzl Max Nordau accept Uganda, provide a haven for must refuse this offer because our needs the left. Herzl and Nordau converse next to the podium. In back of them, a map LEVIN: (jumps to his feet) A map of East oppressed Jews throughout the world, can only be satisfied by Palestine. hangs on the wall, covered by a cloth. Weizmann, Tchlenow, Syrkin, and Levin are Africa?! What is the meaning of this?! and demonstrate that we’re able to form taking their places and looking over papers. Zangwill stands front center stage, (All freeze.) a government. -

Shelomo Dov Goitein

SHELOMO DOV --GOITEI-N SHELOMO DOV GOITEIN: IN MEMORIAM The man we honor here, whose quiet and unassuming manner almost left his passage through this institution unobserved, typ ifies the purpose and function of the Institute for Advanced Study-that of enabling the scholar to pursue his work in the most supportive ambience possible. His gentle nature and vast schol arship, his courtesy and erudition will be addressed in the printed talks which this booklet contains. I only wish to add a brief word to record the extraordinary grace oflife and learning Shelomo Dov Goitein brought to our community and to express, on behalf of so many here whose lives he touched, the pride and pleasure we felt in his presence and our gratitude for the kindness and friendship he so warmly and generously bestowed. HARRY WOOLF Princeton Director New jersey, 1985 Institute for Advanced Study MEMORIAL COMMENTS March 13, 1985 Since I happen to be serving as Executive Officer of the School of Historical Studies this year, it has fallen to my lot to welcome you here this afternoon as we honor the memory of Shelomo Goitein, a member of the School from 1971 through 1975 and then a long term visitor until his death on February 6, I985. I feel especially privileged by this happenstance because Professor Goitein was, in a way, the first introduction I had to life as it can be and should be at the Institute. When I came to the Institute in I973, I was working on certain works of art that involved some rather recondite texts in Hebrew, a language of which I am quite ignorant. -

Judaica Olomucensia

Judaica Olomucensia 2015/1 Special Issue Jewish Printing Culture between Brno, Prague and Vienna in the Era of Modernization, 1750–1850 Editor-in-Chief Louise Hecht Editor Matej Grochal This issue was made possible by a grant from Palacký University, project no. IGA_FF_2014_078 Table of Content 4 Introduction Louise Hecht 11 The Lack of Sabbatian Literature: On the Censorship of Jewish Books and the True Nature of Sabbatianism in Moravia and Bohemia Miroslav Dyrčík 30 Christian Printers as Agents of Jewish Modernization? Hebrew Printing Houses in Prague, Brno and Vienna, 1780–1850 Louise Hecht 62 Eighteenth Century Yiddish Prints from Brünn/Brno as Documents of a Language Shift in Moravia Thomas Soxberger 90 Pressing Matters: Jewish vs. Christian Printing in Eighteenth Century Prague Dagmar Hudečková 110 Wolf Pascheles: The Family Treasure Box of Jewish Knowledge Kerstin Mayerhofer and Magdaléna Farnesi 136 Table of Images 2015/1 – 3 Introduction Louise Hecht Jewish Printing Culture between Brno, Prague and Vienna in the Era of Modernization, 1750–1850 The history of Jewish print and booklore has recently turned into a trendy research topic. Whereas the topic was practically non-existent two decades ago, at the last World Congress of Jewish Studies, the “Olympics” of Jewish scholarship, held in Jerusalem in August 2013, various panels were dedicated to this burgeoning field. Although the Jewish people are usually dubbed “the people of the book,” in traditional Jewish society authority is primarily based on oral transmission in the teacher-student dialog.1 Thus, the innovation and modernization process connected to print and subsequent changes in reading culture had for a long time been underrated.2 Just as in Christian society, the establishment of printing houses and the dissemination of books instigated far-reaching changes in all areas of Jewish intellectual life and finally led to the democratization of Jewish culture.3 In central Europe, the rise of publications in the Jewish vernacular, i.e. -

The Jewish Journal of Sociology

THE JEWISH JOURNAL OF SOCIOLOGY VOLUME XIV NO. 2 DECEMBER 1972 CONTENTS The Conversion of Karl Marx's Father Lewis S. Fetter 149 A Merger of Synagogues in San Francisco carolyn L. Wiener 167 A Note on Marriage Trends among Jews in Italy Sergio Della Pergola 197 Is Antisemitism a Cognitive Simplification? Some Observations on Australian Neo-Nazis John 3. Ray 207 Synagogue Statistics and the Jewish Population of Great Britain, 1900-70 5.3. Prais 215 The Jewish Vote in Romania between the Two World Wars Bela Vago 229 Book Reviews 245 Chronicle 262 Books Received 267 Notes on Contributors 269 PUBLISHED TWICE YEARLY on behalf of the World Jewish. Congress by William Heinemann Ltd Annual Subscription 7•o (U.S. tj) post fret Single Copies 75p ($2.25) Applications for subscription should be addressed to the Managing Editor, The Jewish Journal of Sociology, 55 New Cavendish Street, London WsM 8BT EDITOR Maurice Freedman MANAGING EDITOR Judith Freedman ADVISORY BOARD R. Bachi (Israel) Eugene Minkowski (France) Andre Chouraqui (France & Israel) S. J. Prais (Britain) M. Davis (Israel) Louis Rosenberg (Canada) S. N. Eiscnstadt (Israel) H. L. Shapiro (USA) Nathan Glazer (USA) A. Steinberg (Britain) J. Katz (Israel) A. Tartakower (Israel) 0. Klineberg (USA) © THE JEWISH CONGRESS 1972 PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN BY BUTLER AND TANNER LTD FROME AND LONDON BOOKS REVIEWED Awhoi Title Reviewer Page Joseph Brandes and Immigrants to Freedom H. M. Brotz 245 Martin Douglas H. Desroche and Introduction ant sciences David Martin 246 J. Séguy, eds. humaines des religions A. S. Diamond Primitive Law Maurice Freedman 247 Joseph W. -

Narratology, Hermeneutics, and Midrash

Poetik, Exegese und Narrative Studien zur jüdischen Literatur und Kunst Poetics, Exegesis and Narrative Studies in Jewish Literature and Art Band 2 / Volume 2 Herausgegeben von / edited by Gerhard Langer, Carol Bakhos, Klaus Davidowicz, Constanza Cordoni Constanza Cordoni / Gerhard Langer (eds.) Narratology, Hermeneutics, and Midrash Jewish, Christian, and Muslim Narratives from the Late Antique Period through to Modern Times With one figure V&R unipress Vienna University Press Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. ISBN 978-3-8471-0308-0 ISBN 978-3-8470-0308-3 (E-Book) Veröffentlichungen der Vienna University Press erscheineN im Verlag V&R unipress GmbH. Gedruckt mit freundlicher Unterstützung des Rektorats der Universität Wien. © 2014, V&R unipress in Göttingen / www.vr-unipress.de Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Das Werk und seine Teile sind urheberrechtlich geschützt. Jede Verwertung in anderen als den gesetzlich zugelassenen Fällen bedarf der vorherigen schriftlichen Einwilligung des Verlages. Printed in Germany. Titelbild: „splatch yellow“ © Hazel Karr, Tochter der Malerin Lola Fuchs-Carr und des Journalisten und Schriftstellers Maurice Carr (Pseudonym von Maurice Kreitman); Enkelin der bekannten jiddischen Schriftstellerin Hinde-Esther Singer-Kreitman (Schwester von Israel Joshua Singer und Nobelpreisträger Isaac Bashevis Singer) und Abraham Mosche Fuchs. Druck und Bindung: CPI Buch Bücher.de GmbH, Birkach Gedruckt auf alterungsbeständigem Papier. Contents Constanza Cordoni / Gerhard Langer Introduction .................................. 7 Irmtraud Fischer Reception of Biblical texts within the Bible: A starting point of midrash? . 15 Ilse Muellner Celebration and Narration. Metaleptic features in Ex 12:1 – 13,16 .