"Master and Man," and Other Parables and Tales

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Problem of Folklorism in Russian Prose of Early Twentieth Century Oshchepkova AI* and Ivanova OI

Research Article Global Media Journal 2016 Vol.Special Issue ISSN 1550-7521 No.S3:25 The Problem of Folklorism in Russian Prose of Early Twentieth Century Oshchepkova AI* and Ivanova OI Department of Philology, North-Eastern Federal University, Russia *Corresponding author: Anna Igorevna Oshchepkova, Head of the Department of Philology, North-Eastern Federal University in Yakutsk, 677000, Russia, the Sakha Republic (Yakutia), Yakutsk, Belinsky st., 58, Russia, Tel: +7 (4112) 49-68-53; E-mail: [email protected] Received date: May 05, 2016; Accepted date: June 20, 2016; Published date: June 28, 2016 Copyright: © 2016, Oshchepkova AI, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Citation: Oshchepkova AI, Ivanova OI. The Problem of Folklorism in Russian Prose of early Twentieth Century. Global Media Journal. 2016, S3:25 Introduction Abstract The article deals with the study of folklorism in the literary text in synchronous aspect, which is of more typological, Russian literature at the beginning of the twentieth theorized character; its peculiarity is to use folklore century deals with cardinal worldview shift towards the consciously having a certain purpose in mind. The synchronic loss of infernality, coherence of poetical view, appearance approach is characterized by special literary folklorism, with its of trend towards strengthening foundations associated focus on the folklorism and folkloristic tradition, but not on with form and creativeness. Henceforth, the prose was folklore itself; although, another type of association between searching for experiments directly with the form of the literary text and folklore is possible; it is determined not by piece: from the speech level to the reconstruction of author's conscious intention, but rather by the text and genre model, originating in folklore tradition. -

Twenty-Three Tales

Twenty-Three Tales Author(s): Tolstoy, Leo Nikolayevich (1828-1910) Publisher: Grand Rapids, MI: Christian Classics Ethereal Library Description: Famous for his longer novels, War and Peace and Anna Karenina, Leo Tolstoy displays his mastery of the short story in Twenty-Three Tales. This volume is organized by topic into seven different segments. Part I is filled with stories for children, while Part 2 is filled with popular stories for adult. In Part 3, Tolstoy discreetly condemns capitalism in his fairy tale "Ivan the Fool." Part 4 contains several short stories, which were originally published with illustrations to encourage the inexpensive reproduction of pictorial works. Part 5 fea- tures a number of Russian folk tales, which address the themes of greed, societal conflict, prayer, and virtue. Part 6 contains two French short stories, which Tolstoy translated and modified. Finally, Part 7 contains a group of parabolic short stories that Tolstoy dedicated to the Jews of Russia, who were persecuted in the early 1900©s. Entertaining for all ages, Tolstoy©s creative short stories are overflowing with deeper, often spiritual, meaning. Emmalon Davis CCEL Staff Writer Subjects: Slavic Russian. White Russian. Ukrainian i Contents Title Page 1 Preface 2 Part I. Tales for Children: Published about 1872 5 1. God Sees the Truth, but Waits 6 2. A Prisoner in the Caucasus 13 3. The Bear-Hunt 33 Part II: Popular Stories 40 4. What Men Live By (1881) 41 5. A Spark Neglected Burns the House (1885) 57 6. Two Old Men (1885) 68 7. Where Love Is, God Is (1885) 85 Part III: A Fairy Tale 94 8. -

The Semiotics of Advertising In

THE SEMIOTICS OF ADVERTISING IN POST-SOCIALIST RUSSIA: CULTURALLY SIGNIFICANT MEANINGS IN TELEVISION COMMERCIALS DURING THE PERIOD OF TRANSITION AND GLOBALIZATION By Alexander Minbaev Submitted to Central European University History Department In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Supervisor: Professor Marsha Siefert CEU eTD Collection Second Reader: Professor György Endre Szönyi Budapest, Hungary 2013 Abstract This thesis aims to answer a research question of how television commercials appealed to Russian national identity using culturally significant meanings in post-socialist context. In order to do so the thesis examines television commercials adopting semiotic approach. Using of semiotics presupposes the analysis of advertisements as system of signs and as narratives. Commercials are analyzed within their historical context from the late 1980s to the early 2000s. Thesis focuses on the culturally significant meanings deployed in the television advertising through folklore, nostalgia, stereotypes and history in order to appeal to Russian national identity. Commercials chosen for semiotic analysis are taken from different periods of post- socialist Russian history and are examined as case studies, each of which appealing to Russianness using specific techniques, thus comprising a unique style of Russian advertising. Depending on a particular time period within the development of Russian post-socialist advertising, different methods were applied to appeal to potential consumers through exploitations of shared beliefs and values, including national identity that forms the continuous field within the frame of post-socialist advertising. Using semiotic tools from the studies of signs, such as binary opposition, the thesis examines commercials both interpretatively and within their historical context. -

Recollecting Wondrous Moments: Father Pushkin, Mother Russia, and Intertextual Memory in Tatyana Tolstaya's "Night" and "Limpopo"

Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature Volume 28 Issue 2 Article 9 6-1-2004 Recollecting Wondrous Moments: Father Pushkin, Mother Russia, and Intertextual Memory in Tatyana Tolstaya's "Night" and "Limpopo" Karen R. Smith Clarion University Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/sttcl Part of the Slavic Languages and Societies Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Smith, Karen R. (2004) "Recollecting Wondrous Moments: Father Pushkin, Mother Russia, and Intertextual Memory in Tatyana Tolstaya's "Night" and "Limpopo"," Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature: Vol. 28: Iss. 2, Article 9. https://doi.org/10.4148/2334-4415.1587 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recollecting Wondrous Moments: Father Pushkin, Mother Russia, and Intertextual Memory in Tatyana Tolstaya's "Night" and "Limpopo" Abstract With their references to Alexander Pushkin, Tolstaya's "Night" and "Limpopo" respond to the cultural crisis of 1980s Russia, where literary language, bent for so long into the service of totalitarianism, suffers the scars of amnesia. Recycling Pushkin's tropes, particularly his images of feminine inspiration derived from the cultural archetype of Mother Russia, Tolstaya's stories appear nostalgically to rescue Russia's literary memory, but they also accentuate the crisis of the present, the gap between the apparel of literary language and that which it purports to clothe. -

Mariinsky Ballet & Orchestra

CAL PERFORMANCES PRESENTS PROGRAM Wednesday, October 10, 2012, 8pm PROGRAM Thursday, October 11, 2012, 8pm Friday, October 12, 2012, 8pm Saturday, October 13, 2012, 2pm & 8pm Swan Lake Sunday, October 14, 2012, 3pm Ballet in Four Acts Zellerbach Hall Act I Mariinsky Ballet & Orchestra of the Mariinsky Theatre Act II St. Petersburg, Russia INTERMISSION Valery Gergiev, Artistic & General Director Yury Fateev, Interim Ballet Director Act III Mikhail Agrest, Conductor INTERMISSION The Company Act IV Principals Music Pyotr Il’yich Tchaikovsky Ekaterina Kondaurova, Anastasia Kolegova, Oksana Skoryk Libretto Vladimir Begichev & Vasili Geltzer Yevgeny Ivanchenko, Danila Korsuntsev, Vladimir Schklyarov Choreography Marius Petipa & Lev Ivanov Alexander Sergeev, Maxim Zyuzin Revised Choreography & Stage Direction Konstantin Sergeyev Soloists Set Designer Igor Ivanov Olga Gromova, Maria Shirinkina, Olga Akmatova, Elena Bazhenova, Tatiana Bazhitova, Costume Designer Galina Solovieva Nadezhda Batoeva, Olga Belik, Victoria Brileva, Daria Grigoryeva, Ksenia Dubrovina, Valeria Zhuravleva, Ekaterina Ivannikova, Svetlana Ivanova, Keenan Kampa, Lidia Karpukhina, World Premiere Mariinsky Theatre, St. Petersburg, Victoria Krasnokutskaya, Liubov Kozharskaya, Lilia Lishchuk, Anna Lavrinenko, January 15, 1895 Anastasia Mikheikina, Olga Minina, Anastasia Nikitina, Ksenia Ostreykovskaya, Irina Prokofieva, Premiere of Sergeyev’s Version Mariinsky Theatre, St. Petersburg, Ksenia Romashova, Yulia Stepanova, Alisa Sodoleva, Irina Tolchilshchikova, Tatiana Tiliguzova, -

The Myth of Russian Stupidity in Rfl Lessons

International Scientific-Pedagogical Organization of Philologists (ISPOP) DOI: THE MYTH OF RUSSIAN STUPIDITY IN RFL LESSONS Natalia V. Roitberg PhD in Philology, lecturer University of Haifa (Haifa, Israel) e-mail: [email protected] Abstract. This study addresses the use of folklore materials among advanced and intermediate-level students of Russian. Special attention is devoted to the Russian folk character Ivan the Fool, the myth of Russian stupidity, and mechanisms by which the theme of foolishness presented in Russian folklore and literature. The paper focuses on the reading Russian fairy folk tales of Ivan the Fool (Leo Tolstoy’s “The Tale of Ivan the Fool and his two brothers” and the tale “Before the Cock Crows Thrice” by Vasily Shukshin) and the interpreting Russian proverbs and sayings about fools which are shown as conceptions of the myth of Russian stupidity. It was determined that the use of Russian folktales and proverbs as curriculum materials have a great educational significance, linguistic importance on Russian language teaching, as well as on the Russian language acquisition. Furthermore, folklore materials are considered efficient tools for foreign students’ deeper insight into Russian mentality and folk lore. Keywords: Russian as a foreign language lesson (RFL lesson), folklore materials, fairy tales, Ivan the Fool, the myth of Russian stupidity МИФ О РУССКОЙ ГЛУПОСТИ НА УРОКАХ РКИ Наталья Владимировна Ройтберг Кандидат филологических наук, лектор Хайфский Университет (Хайфа, Израиль) e-mail: [email protected] Аннотация. В статье рассматривается использование материалов устного народного творчества на уроках русского языка как иностранного студентам среднего и продвинутого уровней. Отдельное внимание уделено образу Ивана-дурака, мифу о русской глупости и способам репрезентации темы «простофильства» в русском фольклоре и литературе. -

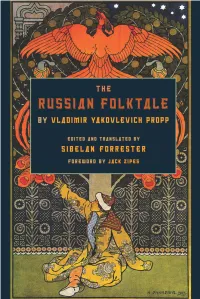

Russian Folktale by Vladimir Yakovlevich Propp

Series in Fairy-Tale Studies General Editor Donald Haase, Wayne State University Advisory Editors Cristina Bacchilega, University of Hawai`i, Mānoa Stephen Benson, University of East Anglia Nancy L. Canepa, Dartmouth College Isabel Cardigos, University of Algarve Anne E. Duggan, Wayne State University Janet Langlois, Wayne State University Ulrich Marzolph, University of Gött ingen Carolina Fernández Rodríguez, University of Oviedo John Stephens, Macquarie University Maria Tatar, Harvard University Holly Tucker, Vanderbilt University Jack Zipes, University of Minnesota A complete listing of the books in this series can be found online at wsupress.wayne.edu W5884.indb ii 8/7/12 10:18 AM THE RUSSIAN FOLKTALE BY VLADIMIR YAKOVLEVICH PROPP EDITED AND TRANSLATED BY SIBELAN FORRESTER FOREWORD BY JACK ZIPES Wayne State University Press Detroit W5884.indb iii 8/7/12 10:18 AM © 2012 by Wayne State University Press, Detroit, Michigan 48201. English translation published by arrangement with the publishing house Labyrinth-MP. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without formal permission. Manufactured in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data 880-01 Propp, V. IA. (Vladimir IAkovlevich), 1895–1970, author. [880-02 Russkaia skazka. English. 2012] Th e Russian folktale by Vladimir Yakovlevich Propp / edited and translated by Sibelan Forrester ; foreword by Jack Zipes. pages ; cm. — (Series in fairy-tale studies) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8143-3466-9 (paperback : alkaline paper) — ISBN 978-0-8143-3721-9 (ebook) 1. Tales—Russia (Federation)—History and criticism. 2. Fairy tales—Classifi cation. 3. Folklore—Russia (Federation) I. -

Pn DATE 81 NOTE 17P

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 230 953 CS 207 615 AUTHOR Haviland, Virginia, Comp. TITLE Children's Books, 1980: A List of Books for Preschool through Junior High School Age. INSTITUTION Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. pn DATE 81 NOTE 17p. -AVAILABL4FROMSuperintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402. PUB TYPE Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Adolescent Literature; Annotate Bibliographies; Art; Biographies; *Books; *Child ens Literature; Elementary Secondary Education; iction; Folk Culture; History; Hobbies; Poetry; *Reading Aloud ,to Others; *Reading Instruction; Reading Materials; *Recreational Reading; Sciences ABSTRACT The annotated materials contained in this list of children's books for'1980 have been selected for literary merit, usefulness, and enioyment, and are intended to reflecta year's publis ing in a balance between books to be enjoyed for free reading, those or reading aloud, and those recognized as valuable lor indivi ualized_reading programs or as background andsupplements to the sc ool curriculum. The 159 titles for preschool through junior high s hool age chidren are(divided into the followingareas: (1) pictur and picture story books; (2) first reading; (3) stortses for the mi dle group; (4) fiction for older readers; (5) poetry, rhyMes, and so gs; (6) folklore; (7).history, people, and places; (8) biogra hy; (9) arts and hobbies; and (10) nature and science. Approp iate grade levels for each title are included in the annota ion. (HTH) ******************************************************************.***** * Reproductions sumlied by EDRS-are the best thatcan be made * * Arm the original document. * *********************************************************************** ISSN 0069-3464 Children's Books U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION EDUCATIONAL RESOURCESINFORMATION CENTER IERICt Tho document has bcon reproduced aa received from tho porton or zation ogInatIng Minor change's have been made to Improve 1980 rePrOduchon cjadlay. -

Female Discourses: Powerful and Powerless Speech in Sir Thomas Malory’S Le Morte Darthur

FEMALE DISCOURSES: POWERFUL AND POWERLESS SPEECH IN SIR THOMAS MALORY’S LE MORTE DARTHUR By YEKATERINA ZIMMERMAN A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2005 Copyright 2005 by Yekaterina Zimmerman ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank the chair of my committee, Dr. Diana Boxer, for being my mentor for all these years, for her guidance, emotional support and for having an answer to every question and a solution for every problem. My wholehearted thanks go to my committee members Dr. Will Hasty, Dr. D. Gary Miller and Dr. Marie Nelson for all their kind help, support, guidance and encouragement. This work would not have been possible without them. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ................................................................................................. iii ABSTRACT....................................................................................................................... vi CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................1 Overview.......................................................................................................................1 A Historical Outlook on Le Morte Darthur..................................................................2 Methodology.................................................................................................................4 -

Kikas-Xmaster.Pdf (2.790Mb)

Shooting the Joy of the Rus’ Alcohol Consumption and Alcoholism in Soviet Movies, 1953-1991 Merlin Kikas MASTER’S THESIS – EUROPEAN AND AMERICAN STUDIES FACULTY OF HUMANITIES Supervisor: Pål Kolstø UNIVERSITY OF OSLO Autumn 2012 © The Author 2012 Shooting the Joy of the Rus’: Alcohol Consumption and Alcoholism in Soviet Movies, 1953- 1991 Merlin Kikas http://www.duo.uio.no/ Print: Reprosentralen, University of Oslo ii Abstract The current thesis examines how alcohol consumption and alcoholism were interpreted in Soviet movies between 1953 and 1991, taking into consideration the shifting ideological constraints and anti-alcohol campaigns, as well as alcohol and film politics. With the help of 43 films, this research explores the socio-cultural aspects of drinking as represented in Soviet films, uncovers the beliefs about alcohol consumption and alcoholism, and observes how films as cultural texts reflect society back onto itself. Moreover, through film readings of four Soviet alcoholism movies, the research illustrates how the attitudes towards alcoholics and alcoholism developed during the 1970s and 1980s. The study shows that in a state where, in ideological principle, socialism and alcoholism were incompatible, alcohol consumption was portrayed frequently--although filmmakers were cautions with their cinematic interpretations. Drinking occasions were very often intertwined with humorous situations and sketches that satisfied the audiences’ yearnings for entertainment. The seriousness of certain scenes was hidden or brightened up with the help of catchy phrases or smoothed down through light musical compositions which gave the situation comical connotations. Similarly, it turns out that drinking location, the way alcohol is consumed and alcoholic beverages encompass various allusions both to the nature of the celebration and the social status of the drinker which, in turn, fed various societal clichés. -

A Journey Through Xixth and Xxth Century Russian Literature »

« A journey through XIXth and XXth Century Russian Literature » (Dalipagic Catherine) Literature plays a pregnant role in the life of intellectual Russia. « Here literature is not a luxury, not a diversion. It is bone of the bone, flesh of the flesh, not only of the intelligentsia, but also of a growing number of the common people, intimately woven into their everyday existence, part and parcel of their thoughts, their aspirations, their social, political and economic life. It expresses their collective wrongs and sorrows, their collective hopes and strivings. Not only does it serve to lead the movements of the masses, but it is an integral component element of those movements. In a word, Russian literature is completely bound up with the life of Russian society, and its vitality is but the measure of the spiritual vitality of that society » Thomas Seltzer. I - Russian sentimentalism and preromanticism ( 1790-1820) This period can be considered as a period of transition to the modern age Let me give you a few characteristics of this period: this period is the aftermath of the French revolution, it is characterized by the rise of Napoleon and the Napoleonic wars, the French invasion of Russia in 1812. In Russia, the intellectual ferment will lead to the Decembrist uprising (1825) and it is a culturally chaotic period. A- Change : What was the development in European literary life in the XVIII th century ? In the middle of the eighteenth century, new literary trends began to contest the place of classicism Classical mind of the Enlightenment -

The Firebird and the Fox Jeffrey Brooks Index More Information Www

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-48446-6 — The Firebird and the Fox Jeffrey Brooks Index More Information Index abstraction, 156, 182 for popular culture, 8, 21, 46, 62, 153, Acmeism, 149, 153, 190 194 Aesop, 5, 172, 204 autocracy, 2, 14, 17, 51, 56–59, 99–100, Afanas’ev, Aleksandr N. (folklorist), 5, 20, 106–109, 263 24, 29–30, 45, 230, 234, 242, 250 Diaghilev and, 105–106, 125–129 Afanas’ev, Aleksei Fedorovich, 28–29, 131, political debates about after 1905, 119–124 135, 251–252, 265 avant-garde, 5, 8, 79, 96, 99, 136, 141, 180 agency Bolsheviks and, 170–187, 235 of former serfs, 7 celebrity culture, 147–152 of peasants, 13 Chukovsky, Kornei, and, 210 of people of common origins, 2–6, 16–17 exhibitions, 155 as represented in the lubok,59–63 traditions of rebellion and, 151 of women, 44–46, 144–146 unconventional dress and, 159 Aikhenval’d, Iurii, 120 use of humor, 9, 100, 147 Akhmatova, Anna, 1, 10, 153–154, 168, violence in the imagery of, 187, 206 175, 178, 241 Averchenko, Arkadii, 115, 160 Aksakov, Sergei, 25, 54 Alarm Clock (Budil’nik),62–64, 148–159, 214 Babel, Isaac, 168, 207, 228 Alexander II, Tsar, 2, 13–15, 41, 81, 252 “Death of Dolgushov, The,” 196 Alexander III, Tsar, 16, 52, 57, 96, 106 “My First Goose,” 195 Altman, Natan, 184, 186 Odessa Stories, 196 Andreev, Leonid, 101, 153 Red Cavalry, 195 Annenkov, Iurii, 186, 188, 219, 225 use of the skaz, 195 anniversary of the Revolution, celebration Bakhtin, Mikhail, 22, 35, 115, 181 of, 184–186 Bakst, Leon, 106, 129 anti-Semitism, 137, 142, 152, 210 attack of Benois on, 142