OCR Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

Grey Lodge Occult Review™

May 1 2003 e.v. Issue #5 Grey Lodge Occult Review™ Gems from the Archives Selections from the archived Web-Material C O N T E N T S Mummeries of Resurrection The Cycle of Osiris in Finnegans Wake by Mark L. Troy The Man Who Invented Flying Saucers by John A. Keel SF, Occult Sciences, and Nazi Myths by Manfred Nagl Exegesis excerpts 1974-1982 "The Ten Major Principles of the Gnostic Revelation" by Philip K. Dick I Understand Philip K. Dick by Terence Mckenna Dr. Green and the Goblins of Langley by Jim Schnabel Brother Dave Morehouse D:.I:.A:. Remote Viewer & NDE Experiencer Excerpt from: Psychic Warrior by David Morehouse The Oberg Files by Blue Resonant Human, Ph.D. (Agent BlueBird) EXIT Communication to all Brethren (Information) from Robert De Grimston The Process - Church of the Final Judgement The Gitanjali or `song offerings' by Rabindranath Tagore with an introduction by William B. Yeats Rosa Alchemica by William B. Yeats (Note: PDF) John Dee by Charlotte Fell-Smith (Note: PDF) Serapis A Romance by Georg Ebers (Note: PDF) Home GLORidx Close Window Except where otherwise noted, Grey Lodge Occult Review™ is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 License. Grey Lodge Occult Review™ 2003 e.v. - Issue #5 Mummeries of Resurrection The Cycle of Osiris in Finnegans Wake Mark L. Troy Uppsala 1976 Doctoral dissertation at the University of Uppsala 1976 HTML version prepared by Eric Rosenbloom Kirby Mountain Composition & Graphics 2002 Note: Page numbers from the printed text have been retained in the table of contents to use as approximate guides for the references in the bibliographies, line index, and elsewhere. -

SCHOOL GARDENS.L

CHAPTEIl XI. SCHOOL GARDENS.l By E. G.L'G, 'I'riptis, Thuringia, Germany. C01drnts.-IIistorical Review-Sites and arrangement of Rchool gatdcns-s-Dilterent Rections of fkhool gardens-::\Ianagement-Instruction in School gardens-E\lucu- tional and Economic Significance of School gardens. 1. DISTOIlY. Rchool gardens, in the narrow sense of the term, are a very modern institution; but when considered as including all gardens serving the purpose of instruction, the expression ol Ben Akiba may be indorsed, "there is nothing new under the SUIl," for in a comprehensive sense, school gardens cease to be a modern institution. His- tory teaches that the great Persian King Cyrus the Elder ( 559-5~ B. C.) laid out the first school gardens in Persia, in which the sons of noblemen were instruct ·(1 ill hor- ticulture. King Solomon (1015 B. C.) likewise possessed extensive gardens ill which all kinds of plants were kept, probably for purposes of instruction as well as orna- ment, "from the cedar tree that is in Lebanon even unto the hyssop that springoth out of the wall." The botanical gardens of Italian and other univer -ities belong to school gardens in the broader acceptation of the term. The first to establish a garden of this kind was Gaspar de Gabriel, a wealthy Italian nobleman, who, in 1525 A. D., laid out the first one in Tuscany. Many Italian cities, Venice, Milan, and Naples followed this ex- ample. Pope Pius V (1566-1572) cstabli hed one in Bologna, and Duke Franci . of Tuscany (1574-1584) one in Florence. At that time, almost every important city in Italy possessed its botanical garden. -

1995-1996 Literary Magazine

á Shabash AMERICAN EMBASSY MIDDLE SCHOOL 1995-1996 LITERARY MAGAZINE Produced by Ms. Lundsteen’s English Class: Marco Acciarri Youn Joung Choi Bassem Amin Rohan Jetley Erin Brand Tara Lowen-Ault Grace Calma Daniel Luntzel Ajay Chand - Zoe Manickam With special thanks to Mrs. Kochar for her patience and guidance. Cover Design: Tara Lowen-Ault "" "7'_"'""’/Y"*"‘ ' F! f'\ O f O O f-\ ü Ö O o o o O O ____\. O o O . Q o ° '\ . '.-'.. n, . _',':'. '- -.'.` Q; Z / \ / The Handsome Toad A Trip Down Memory Lane Once upon a time a ugly princess was playing soccer with a solid gold ball in her garden. She slipped and the ball went flying up into the air When I was four, and landed into a nearby lake. “lt’s a throw in!” the umpire called out. My Dad was working in England, The princess went to get the ball but soon He was offered a job in Oman, realized that the ball had sunk. Then in spite of He went for the interview in the morning, herself she saw a toad swimming. I told him,“Daddy wear this tie.lt is fashion.” She said to the toad,”lf you go get my gold ball, He wore it. you can sleep in my bed tonight.” ' He got back in the evening. At first the toad did not think it was a good idea I asked “Daddy are we going to Oman?” but after all she was the princess so she could "Yes,” he said. execute him. So the toad agreed. -

Creating New Animated TV Series for Girls Aged 6-12 in Britain

Creating New Animated TV Series for Girls Aged 6-12 in Britain Lindsay Watson This article focuses on the development and marketing of animated female lead charac- ters on television for an audience of girls aged 6-12 in Britain. Using strategic marketing theory it asks the questions: “What do girls want (to see on screen)?” “How do they get it?” and “How do we (the animation industry) sell it?” The paper reviews 87 starring fe- male lead characters worldwide and finds that most are: 2D in design, feature characters with American accents, have a cast of either group or independent characters and are of either a ‘dramatic’ or ‘dramatic/comedic’ genre. The article concludes that the types of television shows girls are watching could be improved to better meet their needs. It encourages content creators to be brave and test new ideas and offers practical tips to executives, producers and commissioners on development and positioning of new ani- mated television series that will engage their audiences. Personal Preface As an animation producer, academic, and campaigner for indie animation and women’s rights I decided in 2013 that I wanted to answer the question: Why aren’t there more animated female characters on British children’s TV? That year also happened to be the year I launched Animated Women UK – since then a lot has changed! The 1980s was a great time for empowered animated female leads in TV series as merchandisers recognised audience buying power (Perea, 2014). This didn’t translate to the big screen as from 1995 to 2012 most of Pixar’s films featured male leads. -

Classroom to Boardroom: the Role of Gender in Leadership Style, Stereotypes and Aptitude for Command in Public Relations

Public Relations Journal Vol. 5, No. 2, Spring 2011 ISSN 1942-4604 © 2011 Public Relations Society of America Classroom to Boardroom: The Role of Gender in Leadership Style, Stereotypes and Aptitude for Command in Public Relations Victoria Geyer-Semple This study uses scholarly literature grounded in organizational communication theory, feminist perspectives and gender theory on the public relations industry to provide a theoretical framework for primary research conducted on both undergraduate public relations majors and public relations practitioners. Results from primary research (interviews with undergraduate students and a survey administered to public relations practitioners) reveals parallels and disconnects between student expectations and professional realities of the role gender plays in the public relations discipline. To help foster diversity and reduce gendered stereotypes within undergraduate public relations programs and the public relations industry fresh, pedagogical recommendations are explored. Cameron, Lariscy, and Sweep (1992) found that education influences the way public relations is practiced. Thus, with pedagogical changes at the undergraduate level, there is hope for a rebalance of equal gender distribution for female practitioners at all professional levels, as well the capacity to provide more comprehensive and accurate images of the discipline. LITERATURE REVIEW According to a report from Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication, between the years of 1994 and 1995 there were over 10,000 U.S. students majoring in public relations (Benigni, Weaver-Lariscy & Tinkham, 2002). In the fall of 2006, more than 15,000 undergraduate students were majoring in public relations (Becker, Vlad & McLean, 2007). While there has been an increase in students studying the discipline, the industry also continues to grow. -

Mtv Nz November Programme Highlights Vj Search

MTV NOVEMBER PROGRAMME HIGHLIGHTS www.mtv.co.nz October 26, 2006 CHANNEL 35, SKY DIGITAL TUNE IN FOR THESE GREAT MTV SHOWS IN NOVEMBER MTV EUROPE MUSIC AWARDS SEE IT FIRST ON MTV NZ FRIDAY NOVEMBER 2 nd @ 11am & 7pm He brought sexy back to the Video Music Awards in NY and now he’s taking it over to Europe to the European Music Awards (EMA’s). That’s right, the man himself Justin Timberlake has been announced as the host with the most for this year’s EMAs in Copenhagen. Snoop Dogg and Rihanna will also join the ranks of Muse, Nelly Furtado, Keane, The Killers and P Diddy all performing in the show. The biggest music event in Europe can now also boast the addition of hip-hop legend Fat Joe as the host of the Red Carpet Special, as well as Oscar winner and Hollywoodland star Adrien Brody, confirmed as a presenter. Even the MTV EMA 2005 host, Borat, will make a special appearance at the event, so expect the unexpected! MONDAY NIGHT’S A BITCH EXCLUSIVE TO MTV NZ EVERY MONDAY FROM 8PM – 12AM Give your inner bitch a boost with the brand new series of Laguna Beach, Tiara Girls, Rich Girls & Power Girls. Also catch My Super Sweet 16, 8 th & Ocean and the Hills, EXCLUSIVE to MTV NZ. Laguna Beach : NZ premier every Monday @ 8pm. Catch the It's season three of Laguna Beach: The Real Orange County - and a whole new generation gets ready to bring the drama. Cliques will clash, secrets will be revealed and hearts will be broken. -

Performance Theory

Performance Theory “Reading Performance Theory by Richard Schechner again, three decades after its first edition, is like meeting an old friend and finding out how much of him/her has been with you all along this way.” Augusto Boal “It is an indispensable text in all aspects of the new discipline of Performance Studies. It is in many ways an eye-opener par- ticularly in its linkage of theater to other performance genres.” Ngu˜ gı˜ wa Thiong’o, University of California “Richard Schechner has defined the parameters of con- temporary performance with an originality and insight that make him indispensable to contemporary theatrical thought. For many years, both scholars and artists have been inspired by his unique and powerful perspective.” Richard Foreman “Schechner has a place in every theater history textbook for his ground-breaking work in environmental theater in the 1960s and 1970s and for his vision in helping to found the discipline of performance studies.” Rebecca Schneider “Richard Schechner is the master teacher and the master conversant on the transformative power of performance to both performer and spectator, at its deepest level. Perform- ance Theory is the essential book which brilliantly illuminates the world as a performance space on stage and off.” Anna Deveare Smith A highlands Papua New Guinea man takes a break from dancing (see chapter 4, “From ritual to theater and back: the efficacy– entertainment braid”). Richard Schechner Performance Theory Revised and expanded edition, with a new preface by the author London and New York Essays on Performance Theory published 1977 by Ralph Pine, for Drama School Specialists Second edition first published 1988 by Routledge 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 First published in the United Kingdom 1988 by Routledge First published in Routledge Classics 2003 by Routledge 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2004. -

Reality TV and Interpersonal Relationship Perceptions

REALITY TV AND INTERPERSONAL RELATIONSHIP PERCEPTIONS ___________________________________________ A Dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of MissouriColumbia ______________________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy __________________________________________________ by KRISTIN L. CHERRY Dr. Jennifer Stevens Aubrey, Dissertation Supervisor MAY 2008 © Copyright by Kristin Cherry 2008 All Rights Reserved The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled REALITY TV AND INTERPERSONAL RELATIONSHIP PERCEPTIONS presented by Kristin L. Cherry, a candidate for the degree of doctor of philosophy, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Professor Jennifer Stevens Aubrey Professor Michael Porter Professor Jon Hess Professor Mary Jeanette Smythe Professor Joan Hermsen ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to acknowledge all of my committee members for their helpful suggestions and comments. First, I would like to thank Jennifer Stevens Aubrey for her direction on this dissertation. She spent many hours providing comments on earlier drafts of this research. She always made time for me, and spent countless hours with me in her office discussing my project. I would also like to thank Michael Porter, Jon Hess, Joan Hermsen, and MJ Smythe. These committee members were very encouraging and helpful along the process. I would especially like to thank them for their helpful suggestions during defense meetings. Also, a special thanks to my fiancé Brad for his understanding and support. Finally, I would like to thank my parents who have been very supportive every step of the way. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS……………………………………………………………..ii LIST OF FIGURES……………………………………………………………..…….…iv LIST OF TABLES………………………………………………………………….……v ABSTRACT………………………………………………………….…………………vii Chapter 1. -

2005Newtitle 000.Pdf

The Combined ® Book Exhibit Welcome to BookExpo America 2005 Dear Industry Colleague: BookExpo America and the Combined Book Exhibit® welcome you to BookExpo America’s 1st Annual BEA New Title Showcase. We are pleased that you have taken the time to visit this new and featured exhibit. We invite you to peruse the hundreds of titles and numerous publishers on display. Many of the participating publishers also have booth space on the show floor, and their booth numbers are indicated in the show catalog. For those publishers that do not have booth space on the show floor, we have provided you with their company and other relevant information so you can contact them after the show has ended. Please take this catalog with our compliments, and keep it along with your BEA Show Directory as a record of what you saw, and whom you visited at the 2005 Show. At the conclusion of the 2005 show, this catalog will be included on the BookExpo America Web Site (bookexpoamerica.com), and Combined Book Exhibit® web site (combinedbook.com) in pdf format. Once again, thank you for visiting this exhibit, and hope you have a successful, rewarding experience at this years show. Sincerely, Chris McCabe Jon Malinowski BEA Show Director President BookExpo America Combined Book Exhibit® 383 Main Avenue 277 White Street Norwalk, CT 06851 Buchanan, NY 10511 Look for the 2nd Annual BEA New Title Showcase In Washington D.C. May 19-21, 2006 2005 BEA NEW TITLE SHOWCASE 2 Down Press, Inc. Absolute Press 12438 Moor Park St., #241 PO Box 16175 Studio City, CA 91604 Encino, CA 91416 Tel: 702-413-4373 Tel: 818-999-4419; Fax: 818-992-0091 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] URL: www.aperfectswing.com Key Contact Information 1. -

A Distinctive Voice in the Antipodes: Essays in Honour of Stephen A. Wild

ESSAYS IN HONOUR OF STEPHEN A. WILD Stephen A. Wild Source: Kim Woo, 2015 ESSAYS IN HONOUR OF STEPHEN A. WILD EDITED BY KIRSTY GILLESPIE, SALLY TRELOYN AND DON NILES Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: A distinctive voice in the antipodes : essays in honour of Stephen A. Wild / editors: Kirsty Gillespie ; Sally Treloyn ; Don Niles. ISBN: 9781760461119 (paperback) 9781760461126 (ebook) Subjects: Wild, Stephen. Essays. Festschriften. Music--Oceania. Dance--Oceania. Aboriginal Australian--Songs and music. Other Creators/Contributors: Gillespie, Kirsty, editor. Treloyn, Sally, editor. Niles, Don, editor. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover photograph: ‘Stephen making a presentation to Anbarra people at a rom ceremony in Canberra, 1995’ (Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies). This edition © 2017 ANU Press A publication of the International Council for Traditional Music Study Group on Music and Dance of Oceania. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are advised that this book contains images and names of deceased persons. Care should be taken while reading and viewing. Contents Acknowledgements . vii Foreword . xi Svanibor Pettan Preface . xv Brian Diettrich Stephen A . Wild: A Distinctive Voice in the Antipodes . 1 Kirsty Gillespie, Sally Treloyn, Kim Woo and Don Niles Festschrift Background and Contents . -

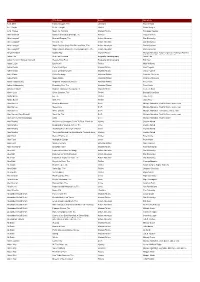

List of All the Audiobooks That Are Multiuse (Pdf 608Kb)

Authors Title Name Genre Narrators A. D. Miller Faithful Couple, The Literature Patrick Tolan A. L. Gaylin If I Die Tonight Thriller Sarah Borges A. M. Homes Music for Torching Modern Fiction Penelope Rawlins Abbi Waxman Garden of Small Beginnings, The Humour Imogen Comrie Abie Longstaff Emerald Dragon, The Action Adventure Dan Bottomley Abie Longstaff Firebird, The Action Adventure Dan Bottomley Abie Longstaff Magic Potions Shop: The Blizzard Bear, The Action Adventure Daniel Coonan Abie Longstaff Magic Potions Shop: The Young Apprentice, The Action Adventure Daniel Coonan Abigail Tarttelin Golden Boy Modern Fiction Multiple Narrators, Toby Longworth, Penelope Rawlins, Antonia Beamish, Oliver J. Hembrough Adam Hills Best Foot Forward Biography Autobiography Adam Hills Adam Horovitz, Michael Diamond Beastie Boys Book Biography Autobiography Full Cast Adam LeBor District VIII Thriller Malk Williams Adèle Geras Cover Your Eyes Modern Fiction Alex Tregear Adèle Geras Love, Or Nearest Offer Modern Fiction Jenny Funnell Adele Parks If You Go Away Historical Fiction Charlotte Strevens Adele Parks Spare Brides Historical Fiction Charlotte Strevens Adrian Goldsworthy Brigantia: Vindolanda, Book 3 Historical Fiction Peter Noble Adrian Goldsworthy Encircling Sea, The Historical Fiction Peter Noble Adriana Trigiani Supreme Macaroni Company, The Modern Fiction Laurel Lefkow Aileen Izett Silent Stranger, The Thriller Bethan Dixon-Bate Alafair Burke Ex, The Thriller Jane Perry Alafair Burke Wife, The Thriller Jane Perry Alan Barnes Death in Blackpool Sci Fi Multiple Narrators, Paul McGann, and a. cast Alan Barnes Nevermore Sci Fi Multiple Narrators, Paul McGann, and a. cast Alan Barnes White Ghosts Sci Fi Multiple Narrators, Tom Baker, and a. cast Alan Barnes, Gary Russell Next Life, The Sci Fi Multiple Narrators, Paul McGann, and a.