Origins of the Moken Sea Gypsies Inferred from Mitochondrial Hypervariable Region and Whole Genome Sequences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Fi~Eeting Encounter with the Moken Cthe Sea Gypsies) in Southern Thailand: Some Linguistic and General Notes

A FI~EETING ENCOUNTER WITH THE MOKEN CTHE SEA GYPSIES) IN SOUTHERN THAILAND: SOME LINGUISTIC AND GENERAL NOTES by Christopher Court During a short trip (3-5 April 1970) to the islands of King Amphoe Khuraburi (formerly Koh Kho Khao) in Phang-nga Province in Southern Thailand, my curiosity was aroused by frequent references in conversation with local inhabitants to a group of very primitive people (they were likened to the Spirits of the Yellow Leaves) whose entire life was spent nomadically on small boats. It was obvious that this must be the Moken described by White ( 1922) and Bernatzik (1939, and Bernatzik and Bernatzik 1958: 13-60). By a stroke of good fortune a boat belonging to this group happened to come into the beach at Ban Pak Chok on the island of Koh Phrah Thong, where I was spending the afternoon. When I went to inspect the craft and its occupants it turned out that there were only women and children on board, the one man among the occupants having gone ashore on some errand. The women were extremely shy. Because of this, and the failing light, and the fact that I was short of film, I took only two photographs, and then left the people in peace. Later, when the man returned, I interviewed him briefly elsewhere (see f. n. 2) collecting a few items of vocabulary. From this interview and from conversations with the local residents, particularly Mr. Prapa Inphanthang, a trader who has many dealings with the Moken, I pieced together something of the life and language of these people. -

Color Terms in Thailand*

8th International Conference on Humanities, Psychology and Social Science October 19 – 21, 2018 Munich, Germany Color Terms in Thailand* Kanyarat Unthanon1 and Rattana Chanthao2 Abstract This article aims to synthesize the studies of color terms in Thailand by language family. The data’s synthesis was collected from articles, theses and research papers totaling 23 works:13 theses, 8 articles and 2 research papers. The study was divided into 23 works in five language families in Thailand : 9 works in Tai, 3 works in Austro-Asiatic (Mon-Khmer), 2 works in Sino-Tibetan, 2 works in Austronesian and 2 works in two Hmong- Mien. There are also 5 comparative studies of color terms in the same family and different families. The studies of color terms in Austro-Asiatic, Sino-Tibetan, Austronesian and Hmong- Mien in Thailand have still found rare so it should be studied further, especially, study color terms of languages in each family and between different families, both in diachronic and synchronic study so that we are able to understand the culture, belief and world outlook of native speakers through their color terms. Keywords: Color terms, Basic color term, Non-basis color term, Ethic groups * This article is a part of a Ph.D. thesis into an article “Color Terms in Modern Thai” 1 Ph.D.student of Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Khon Kaen University, Thailand 2Assistant Professor of Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Khon Kaen University, Thailand : Thesis’s Advisor 1. Background The studies of color terms in Thailand are the research studies of languages in ethnic linguistics (Ethnolinguistics) by collecting language data derived directly from the key informants, which is called primary data or collection data from documents which is called secondary data. -

The Linguistic Background to SE Asian Sea Nomadism

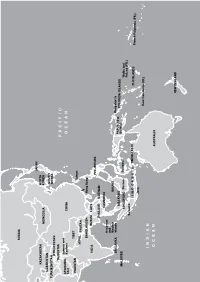

The linguistic background to SE Asian sea nomadism Chapter in: Sea nomads of SE Asia past and present. Bérénice Bellina, Roger M. Blench & Jean-Christophe Galipaud eds. Singapore: NUS Press. Roger Blench McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research University of Cambridge Department of History, University of Jos Correspondence to: 8, Guest Road Cambridge CB1 2AL United Kingdom Voice/ Ans (00-44)-(0)1223-560687 Mobile worldwide (00-44)-(0)7847-495590 E-mail [email protected] http://www.rogerblench.info/RBOP.htm This printout: Cambridge, March 21, 2017 Roger Blench Linguistic context of SE Asian sea peoples Submission version TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction 3 2. The broad picture 3 3. The Samalic [Bajau] languages 4 4. The Orang Laut languages 5 5. The Andaman Sea languages 6 6. The Vezo hypothesis 9 7. Should we include river nomads? 10 8. Boat-people along the coast of China 10 9. Historical interpretation 11 References 13 TABLES Table 1. Linguistic affiliation of sea nomad populations 3 Table 2. Sailfish in Moklen/Moken 7 Table 3. Big-eye scad in Moklen/Moken 8 Table 4. Lake → ocean in Moklen 8 Table 5. Gill-net in Moklen/Moken 8 Table 6. Hearth on boat in Moklen/Moken 8 Table 7. Fishtrap in Moklen/Moken 8 Table 8. ‘Bracelet’ in Moklen/Moken 8 Table 9. Vezo fish names and their corresponding Malayopolynesian etymologies 9 FIGURES Figure 1. The Samalic languages 5 Figure 2. Schematic model of trade mosaic in the trans-Isthmian region 12 PHOTOS Photo 1. Orang Laut settlement in Riau 5 Photo 2. -

A New Method of Classification for Tai Textiles

A New Method of Classification for Tai Textiles Patricia Cheesman Textiles, as part of Southeast Asian traditional clothing and material culture, feature as ethnic identification markers in anthropological studies. Textile scholars struggle with the extremely complex variety of textiles of the Tai peoples and presume that each Tai ethnic group has its own unique dress and textile style. This method of classification assumes what Leach calls “an academic fiction … that in a normal ethnographic situation one ordinarily finds distinct tribes distributed about the map in an orderly fashion with clear-cut boundaries between them” (Leach 1964: 290). Instead, we find different ethnic Tai groups living in the same region wearing the same clothing and the same ethnic group in different regions wearing different clothing. For example: the textiles of the Tai Phuan peoples in Vientiane are different to those of the Tai Phuan in Xiang Khoang or Nam Nguem or Sukhothai. At the same time, the Lao and Tai Lue living in the same region in northern Vietnam weave and wear the same textiles. Some may try to explain the phenomena by calling it “stylistic influence”, but the reality is much more profound. The complete repertoire of a people’s style of dress can be exchanged for another and the common element is geography, not ethnicity. The subject of this paper is to bring to light forty years of in-depth research on Tai textiles and clothing in the Lao People’s Democratic Republic (Laos), Thailand and Vietnam to demonstrate that clothing and the historical transformation of practices of social production of textiles are best classified not by ethnicity, but by geographical provenance. -

THAILAND Submission to the CERD Committee Coalition on Racial

Shadow Report on Eliminating Racial Discrimination: THAILAND Submission to the CERD Committee 1 Coalition on Racial Discrimination Watch Preamble: 1. “ We have a distinct way of life, settlement and cultivation practices that are intricately linked with nature, forests and wild life. Our ways of life are sustainable and nature friendly and these traditions and practices have been taught and passed on from one generation to the next. But now because of State policies and waves of modernisation we are struggling to preserve and maintain our traditional ways of life” Mr. Joni Odochao, Intellectual, Karen ethnic, Opening Speech at the Indigenous Peoples Day Festival in Chiangmai, Northern Thailand 2007 Introduction on Indigenous peoples and ethnic groups in Thailand 1 The coalition was established as a loose network at the Workshop Programme on 5th July 2012 on the Shadow Report on the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (CERD) organised by the Ethnic Studies and Development Center, Sociology Faculty, Chiangmai University in cooperation with Cross Cultural Foundation and the Highland Peoples Taskforce 1 2. The Network of Indigenous Peoples in Thailand2, in the International Working Group for Indigenous Affairs (IWGIA) yearbook on 2008, explained the background of indigenous peoples in Thailand. The indigenous people of Thailand are most commonly referred to as “hill tribes”, sometimes as “ethnic minorities”, and the ten officially recognised ethnic groups are usually called “chao khao” (meaning “hill/mountain people” or “highlanders”). These and other indigenous people live in the North and North-western parts of the country. A few other indigenous groups live in the North-east and indigenous fishing communities and a small population of hunter-gatherers inhabit the South of Thailand. -

Grassroots Solidarity in Revitalising Rural Economy in Asia, Drawing Lessons from Three Case Studies in India, Indonesia, and China

Grassroots Solidarity in Revitalising Rural Economy in Asia, Drawing Lessons from Three Case Studies in India, Indonesia, and China Denison JAYASOORIA Siri Kertas Kajian Etnik UKM (UKM Ethnic Studies Paper Series) Institut Kajian Etnik (KITA) Bangi 2020 Cetakan Pertama / First Printing, 2020 Hak cipta / Copyright Penulis / Author Institut Kajian Etnik (KITA) Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, 2020 Hak cipta terpelihara. Tiada bahagian daripada terbitan ini boleh diterbitkan semula, disimpan untuk pengeluaran atau ditukarkan ke dalam sebarang bentuk atau dengan sebarang alat juga pun, sama ada dengan cara elektronik, gambar serta rakaman dan sebagainya tanpa kebenaran bertulis daripada Institut Kajian Etnik (KITA), Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia terlebih dahulu. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the Institute of Ethnic Studies (KITA), Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia. Diterbitkan di Malaysia oleh / Published in Malaysia by Institut Kajian Etnik, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia 43600 Bangi, Selangor D.E., Malaysia Dicetak di Malaysia oleh / Printed in Malaysia by Penerbit Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia 43600 UKM Bangi, Selangor D.E Malaysia Emel: [email protected] Perpustakaan Negara Malaysia Cataloguing-in-Publication-Data Jayasooria, Denison, 1954- Grassroots Solidarity in Revitalising Rural Economy in Asia, Drawing Lessons from Three Case Studies in India, Indonesia and China / Denison Jayasooria. (Siri Kertas Kajian Etnik UKM ; Bil. 64, Ogos 2020 = UKM Ethnic Studies Paper Series ; No.64, August 2020) ISBN 978-967-0741-61-1 1. Rural development--Case studies. 2. Rural development--Case studies--India. -

ASIA-PACIFIC APRIL 2010 VOLUME 59 Focus Asia-Pacific Newsletter of the Asia-Pacific Human Rights Information Center (HURIGHTS OSAKA) December 2010 Vol

FOCUS ASIA-PACIFIC APRIL 2010 VOLUME 59 Focus Asia-Pacific Newsletter of the Asia-Pacific Human Rights Information Center (HURIGHTS OSAKA) December 2010 Vol. 62 Contents Editorial Indigenous Peoples of Thailand This is a short introduction of the indigenous peoples of Thailand and a discussion of their problems. - Network of Indigenous Peoples in Thailand Being Indigenous Page 2 Indigenous Peoples in the Philippines: Continuing Struggle Land is an important part of the survival of the indigenous This is a discussion on the causes of marginalization of the indigenous peoples peoples, be it in Asia, Pacific or elsewhere. Land is not simply in the Philippines, including the role of land necessary for physical existence but for the spiritual, social, laws in facilitating dispossession of land. - Rey Ty and cultural survival of indigenous peoples and the Page 6 continuation of their historical memory. Marriage Brokerage and Human Rights Issues Marginalization, displacement and other forms of oppression This is a presentation on the continuing are experienced by indigenous peoples. Laws and entry of non-Japanese women into Japan with the help of the unregulated marriage development programs displace indigenous peoples from brokerage industry. Suspicion arises on their land. Many indigenous peoples have died because of the industry’s role in human trafficking. - Nobuki Fujimoto them. Discriminatory national security measures as well as Page 10 unwise environmental programs equally displace them. Human Rights Events in the Asia-Pacific Page 14 Modernization lures many young members of indigenous communities to change their indigenous existence; while Announcement traditional wisdom, skills and systems slowly lose their role as English Website Renewed the elders of the indigenous communities quietly die. -

The Ethnography of Tai Yai in Yunnan

LAK CHANG A reconstruction of Tai identity in Daikong LAK CHANG A reconstruction of Tai identity in Daikong Yos Santasombat Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] Cover: The bride (right) dressed for the first time as a married woman. Previously published by Pandanus Books National Library in Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Santasombat, Yos. Lak Chang : a reconstruction of Tai identity in Daikong. Author: Yos Santasombat. Title: Lak chang : a reconstruction of Tai identity in Daikong / Yos Santasombat. ISBN: 9781921536380 (pbk.) 9781921536397 (pdf) Notes: Bibliography. Subjects: Tai (Southeast Asian people)--China--Yunnan Province. Other Authors/Contributors: Thai-Yunnan Project. Dewey Number: 306.089959105135 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. First edition © 2001 Pandanus Books This edition © 2008 ANU E Press iv For my father CONTENTS Preface ix Acknowledgements xii Introduction 1 Historical Studies of the Tai Yai: A Brief Sketch 3 The Ethnography of Tai Yai in Yunnan 8 Ethnic Identity and the Construction of an Imagined Tai Community 12 Scope and Purpose of this Study 16 Chapter One: The Setting 19 Daikong and the Chinese Revolution 20 Land Reform 22 Tai Peasants and Cooperative Farming 23 The Commune 27 Daikong and the Cultural Revolution 31 Lak -

THE PHONOLOGY of PROTO-TAI a Dissertation Presented to The

THE PHONOLOGY OF PROTO-TAI A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Pittayawat Pittayaporn August 2009 © 2009 Pittayawat Pittayaporn THE PHONOLOGY OF PROTO-TAI Pittayawat Pittayaporn, Ph. D. Cornell University 2009 Proto-Tai is the ancestor of the Tai languages of Mainland Southeast Asia. Modern Tai languages share many structural similarities and phonological innovations, but reconstructing the phonology requires a thorough understanding of the convergent trends of the Southeast Asian linguistic area, as well as a theoretical foundation in order to distinguish inherited traits from universal tendencies, chance, diffusion, or parallel development. This dissertation presents a new reconstruction of Proto-Tai phonology, based on a systematic application of the Comparative Method and an appreciation of the force of contact. It also incorporates a large amount of dialect data that have become available only recently. In contrast to the generally accepted assumption that Proto-Tai was monosyllabic, this thesis claims that Proto-Tai was a sesquisyllabic language that allowed both sesquisyllabic and monosyllabic prosodic words. In the proposed reconstruction, it is argued that Proto-Tai had three contrastive phonation types and six places of articulation. It had plain voiceless, implosive, and voiced stops, but lacked the aspirated stop series (central to previous reconstructions). As for place of articulation, Proto-Tai had a distinctive uvular series, in addition to the labial, alveolar, palatal, velar, and glottal series typically reconstructed. In the onset, these consonants can combine to form tautosyllabic clusters or sequisyllabic structures. -

The Effectiveness of the Teacher Training Program in English Grammar for the Filipino English Teachers at Non-Profit Private Schools in Ratchaburi Province, Thailand

The Effectiveness of the Teacher Training Program in English Grammar for the Filipino English Teachers at Non-Profit Private Schools in Ratchaburi Province, Thailand Sr. Serafina S. Castro A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Teaching English as a Second Language Graduate School, Christian University of Thailand B.E. 2558 Copyright Christian University of Thailand iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am deeply grateful to the following significant persons: Dr. Arturo G. Ordonia and Dr. Ruengdet Pankhuenkhat for their guidance and invaluable advice on the organization of this thesis; Asst. Prof. Dr. Singhanat Nomnian for his time and effort in checking this thesis; Miss Zenaida B. Rocamora for her generosity in accepting my invitation to be the trainer of the Teacher Training Program in English Grammar; The 39 Filipino teachers from different non-profit private schools in Ratchaburi province who made themselves available for the Teacher Training Program for six consecutive Sundays; Our Provincial Council of Fr. Francisco Palau Province who gave me the opportunity to broaden my horizons in the Academe; My Community, the Carmelite Missionaries in Thailand, for their unfailing support and countless prayers; Above all, I return the glory and praise to God and a special honor to Our Lady of Mt. Carmel, who has blessed me with perseverance, wisdom and humility in the completion of my work. iv 554022: MAJOR: Master of Arts Program in Teaching English as a Second Language KEYWORDS: EFFECTIVENESS OF ENGLISH TEACHER TRAINING PROGRAM / GRAMMATICAL ERRORS OF FILIPINO ENGLISH TEACHERS / FILIPINO TEACHERS IN RATCHABURI Sr. -

Religion and Its Role in the Filipino Educators' Migratory Experience

Journal of Population and Social Studies (JPSS) Religion and its Role in the Filipino Educators’ Migratory Experience Analiza Liezl Perez-Amurao1* 1 Mahidol University International College, Thailand * Analiza Liezl Perez-Amurao, corresponding author. Email address: [email protected] Submitted: 30 March 2020, Accepted: 24 September 2020, Published: 16 November 2020 Special Issue, 2020. p. S83-S105. http://doi.org/10.25133/JPSSspecial2020.005 Abstract In Thailand, Filipino teachers have become the largest group of foreign teachers. However, in addition to the influence of the usual factors that play out in their mobility, the migratory experience of the Filipino teachers demonstrates that religion plays an essential role in their eventual participation in international migration. By examining the instrumental approach to development via religion, Filipino teachers utilize instrumental and transnational practices to provide themselves with avenues to achieve their goals and enrich their migratory lives. Simultaneously, in helping shape the Filipino teachers’ migration routes and experiences, religion benefits from this relationship by exercising their regulatory functions through the Filipino teachers’ affiliation with their churches. This study ultimately contributes to the discussion of religion’s shifting image and practices that eventually become part of the normativity within a migrant’s transnational space. Keywords Filipino educators; instrumental religion; missiology; teaching profession; Thailand S83 Religion and its Role in the Filipino Educators’ Migratory Experience Introduction As the number of Filipino migrants who work in the teaching profession in Thailand increases, examining and better understanding the factors that propel their movement to the Kingdom have become more pertinent, if only to make more sense of the emerging mobility of Filipino migrants in the region. -

Asia and Oceania Nicole Girard, Irwin Loy, Marusca Perazzi, Jacqui Zalcberg the Country

ARCTIC OCEAN RUSSIA JAPAN KAZAKHSTAN NORTH MONGOLIA KOREA UZBEKISTAN SOUTH TURKMENISTAN KOREA KYRGYZSTAN TAJIKISTAN PACIFIC Jammu and AFGHANIS- Kashmir CHINA TAN OCEAN PAKISTAN TIBET Taiwan NEPAL BHUTAN BANGLADESH Hong Kong INDIA BURMA LAOS PHILIPPINES THAILAND VIETNAM CAMBODIA Andaman and Nicobar BRUNEI SRI LANKA Islands Bougainville MALAYSIA PAPUA NEW SOLOMON ISLANDS MALDIVES GUINEA SINGAPORE Borneo Sulawesi Wallis and Futuna (FR.) Sumatra INDONESIA TIMOR-LESTE FIJI ISLANDS French Polynesia (FR.) Java New Caledonia (FR.) INDIAN OCEAN AUSTRALIA NEW ZEALAND Asia and Oceania Nicole Girard, Irwin Loy, Marusca Perazzi, Jacqui Zalcberg the country. However, this doctrine is opposed by nationalist groups, who interpret it as an attack on ethnic Kazakh identity, language and Central culture. Language policy is part of this debate. The Asia government has a long-term strategy to gradually increase the use of Kazakh language at the expense Matthew Naumann of Russian, the other official language, particularly in public settings. While use of Kazakh is steadily entral Asia was more peaceful in 2011, increasing in the public sector, Russian is still with no repeats of the large-scale widely used by Russians, other ethnic minorities C violence that occurred in Kyrgyzstan and many urban Kazakhs. Ninety-four per cent during the previous year. Nevertheless, minor- of the population speak Russian, while only 64 ity groups in the region continue to face various per cent speak Kazakh. In September, the Chair forms of discrimination. In Kazakhstan, new of the Kazakhstan Association of Teachers at laws have been introduced restricting the rights Russian-language Schools reportedly stated in of religious minorities. Kyrgyzstan has seen a a roundtable discussion that now 56 per cent continuation of harassment of ethnic Uzbeks in of schoolchildren study in Kazakh, 33 per cent the south of the country, and pressure over land in Russian, and the rest in smaller minority owned by minority ethnic groups.