Peruvian Agroforestry Species Clean

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Prosopis Juliflora - Prosopis Pallida Complex: a Monograph

DFID DFID Natural Resources Systems Programme The Prosopis juliflora - Prosopis pallida Complex: A Monograph NM Pasiecznik With contributions from P Felker, PJC Harris, LN Harsh, G Cruz JC Tewari, K Cadoret and LJ Maldonado HDRA - the organic organisation The Prosopis juliflora - Prosopis pallida Complex: A Monograph NM Pasiecznik With contributions from P Felker, PJC Harris, LN Harsh, G Cruz JC Tewari, K Cadoret and LJ Maldonado HDRA Coventry UK 2001 organic organisation i The Prosopis juliflora - Prosopis pallida Complex: A Monograph Correct citation Pasiecznik, N.M., Felker, P., Harris, P.J.C., Harsh, L.N., Cruz, G., Tewari, J.C., Cadoret, K. and Maldonado, L.J. (2001) The Prosopis juliflora - Prosopis pallida Complex: A Monograph. HDRA, Coventry, UK. pp.172. ISBN: 0 905343 30 1 Associated publications Cadoret, K., Pasiecznik, N.M. and Harris, P.J.C. (2000) The Genus Prosopis: A Reference Database (Version 1.0): CD ROM. HDRA, Coventry, UK. ISBN 0 905343 28 X. Tewari, J.C., Harris, P.J.C, Harsh, L.N., Cadoret, K. and Pasiecznik, N.M. (2000) Managing Prosopis juliflora (Vilayati babul): A Technical Manual. CAZRI, Jodhpur, India and HDRA, Coventry, UK. 96p. ISBN 0 905343 27 1. This publication is an output from a research project funded by the United Kingdom Department for International Development (DFID) for the benefit of developing countries. The views expressed are not necessarily those of DFID. (R7295) Forestry Research Programme. Copies of this, and associated publications are available free to people and organisations in countries eligible for UK aid, and at cost price to others. Copyright restrictions exist on the reproduction of all or part of the monograph. -

A Case Study on the Potential of the Multipurpose Prosopis Tree

23 Underutilised crops for famine and poverty alleviation: a case study on the potential of the multipurpose Prosopis tree N.M. Pasiecznik, S.K. Choge, A.B. Rosenfeld and P.J.C. Harris In its native Latin America, the Prosopis tree (also known as Mesquite) has multiple uses as a fuel wood, timber, charcoal, animal fodder and human food. It is also highly drought-resistant, growing under conditions where little else will survive. For this reason, it has been introduced as a pioneer species into the drylands of Africa and Asia over the last two centuries as a means of reclaiming desert lands. However, the knowledge of its uses was not transferred with it, and left in an unmanaged state it has developed into a highly invasive species, where it encroaches on farm land as an impenetrable, thorny thicket. Attempts to eradicate it are proving costly and largely unsuccessful. In 2006, the problem of Prosopis was hitting the headlines on an almost weekly basis in Kenya. Yet amidst calls for its eradication, a pioneering team from the Kenya Forestry Research Institute (KEFRI) and HDRA’s International Programme set out to demonstrate its positive uses. Through a pilot training and capacity building programme in two villages in Baringo District, people living with this tree learned for the first time how to manage and use it to their benefit, both for food security and income generation. Results showed that the pods, milled to flour, would provide a crucial, nutritious food supplement in these famine-prone desert margins. The pods were also used or sold as animal fodder, with the first international order coming from South Africa by the end of the year. -

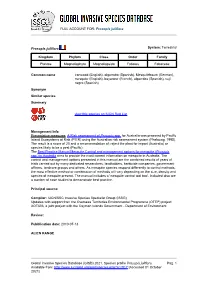

Prosopis Juliflora Global Invasive Species Database (GISD)

FULL ACCOUNT FOR: Prosopis juliflora Prosopis juliflora System: Terrestrial Kingdom Phylum Class Order Family Plantae Magnoliophyta Magnoliopsida Fabales Fabaceae Common name ironwood (English), algarrobo (Spanish), Mesquitebaum (German), mesquite (English), bayarone (French), algarroba (Spanish), cují negro (Spanish) Synonym Similar species Summary view this species on IUCN Red List Management Info Preventative measures: A Risk assessment of Prosopis spp. for Australia was prepared by Pacific Island Ecosystems at Risk (PIER) using the Australian risk assessment system (Pheloung, 1995). The result is a score of 20 and a recommendation of: reject the plant for import (Australia) or species likely to be a pest (Pacific). The Best Practice Manual Mesquite Control and management options for mesquite (Prosopis spp.) in Australia aims to provide the most current information on mesquite in Australia. The control and management options presented in this manual are the combined results of years of trials carried out by many dedicated researchers, landholders, herbicide companies, government officers, landcare groups and others. As mesquite species respond differently to control methods, the most effective method or combination of methods will vary depending on the size, density and species of mesquite present. The manual includes a 'mesquite control tool box'. Included also are a number of case studies to demonstrate best practice. Principal source: Compiler: IUCN/SSC Invasive Species Specialist Group (ISSG) Updates with support from the Overseas -

Ethnobotanical Study of Medicinal Plants Used by the Andean People of Canta, Lima, Peru

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/266388116 Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used by the Andean people of Canta, Lima, Peru Article in Journal of Ethnopharmacology · June 2007 DOI: 10.1016/j.jep.2006.11.018 CITATIONS READS 38 30 3 authors, including: Percy Amilcar Pollito University of São Paulo 56 PUBLICATIONS 136 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE All content following this page was uploaded by Percy Amilcar Pollito on 14 November 2014. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. All in-text references underlined in blue are added to the original document and are linked to publications on ResearchGate, letting you access and read them immediately. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 111 (2007) 284–294 Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used by the Andean people of Canta, Lima, Peru Horacio De-la-Cruz a,∗, Graciela Vilcapoma b, Percy A. Zevallos c a Facultad de Ciencias Biol´ogicas, Universidad Pedro Ruiz Gallo, Lambayeque, Peru b Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Nacional Agraria La Molina, Lima, Peru c Facultad de Ciencias Forestales, Universidad Nacional Agraria La Molina, Lima, Peru Received 14 June 2006; received in revised form 15 November 2006; accepted 19 November 2006 Available online 2 December 2006 Abstract A survey aiming to document medicinal plant uses was performed in Canta Province Lima Department, in the Peruvians Andes of Peru. Hundred and fifty people were interviewed. Enquiries and informal personal conversations were used to obtain information. Informants were men and women over 30 years old, who work in subsistence agriculture and cattle farming, as well as herbalist. -

Checklist of the Vascular Alien Flora of Catalonia (Northeastern Iberian Peninsula, Spain) Pere Aymerich1 & Llorenç Sáez2,3

BOTANICAL CHECKLISTS Mediterranean Botany ISSNe 2603-9109 https://dx.doi.org/10.5209/mbot.63608 Checklist of the vascular alien flora of Catalonia (northeastern Iberian Peninsula, Spain) Pere Aymerich1 & Llorenç Sáez2,3 Received: 7 March 2019 / Accepted: 28 June 2019 / Published online: 7 November 2019 Abstract. This is an inventory of the vascular alien flora of Catalonia (northeastern Iberian Peninsula, Spain) updated to 2018, representing 1068 alien taxa in total. 554 (52.0%) out of them are casual and 514 (48.0%) are established. 87 taxa (8.1% of the total number and 16.8 % of those established) show an invasive behaviour. The geographic zone with more alien plants is the most anthropogenic maritime area. However, the differences among regions decrease when the degree of naturalization of taxa increases and the number of invaders is very similar in all sectors. Only 26.2% of the taxa are more or less abundant, while the rest are rare or they have vanished. The alien flora is represented by 115 families, 87 out of them include naturalised species. The most diverse genera are Opuntia (20 taxa), Amaranthus (18 taxa) and Solanum (15 taxa). Most of the alien plants have been introduced since the beginning of the twentieth century (70.7%), with a strong increase since 1970 (50.3% of the total number). Almost two thirds of alien taxa have their origin in Euro-Mediterranean area and America, while 24.6% come from other geographical areas. The taxa originated in cultivation represent 9.5%, whereas spontaneous hybrids only 1.2%. From the temporal point of view, the rate of Euro-Mediterranean taxa shows a progressive reduction parallel to an increase of those of other origins, which have reached 73.2% of introductions during the last 50 years. -

Vasconcellea Candicans (A

Vasconcellea candicans (A. Gray) A. DC., 1864 (Papayers à petits fruits) Identifiants : 40357/vascan Association du Potager de mes/nos Rêves (https://lepotager-demesreves.fr) Fiche réalisée par Patrick Le Ménahèze Dernière modification le 01/10/2021 Classification phylogénétique : Clade : Angiospermes ; Clade : Dicotylédones vraies ; Clade : Rosidées ; Clade : Malvidées ; Ordre : Brassicales ; Famille : Caricaceae ; Classification/taxinomie traditionnelle : Règne : Plantae ; Sous-règne : Tracheobionta ; Division : Magnoliophyta ; Classe : Magnoliopsida ; Ordre : Violales ; Famille : Caricaceae ; Genre : Vasconcellea ; Synonymes : Carica candicans A. Gray 1854 (nom retenu, selon TPL) (=) basionym, Carica candicans A. Gray ; Nom(s) anglais, local(aux) et/ou international(aux) : Mito , mito (es,pe) ; Rapport de consommation et comestibilité/consommabilité inférée (partie(s) utilisable(s) et usage(s) alimentaire(s) correspondant(s)) : Partie(s) comestible(s){{{0(+x) : fruit0(+x). Utilisation(s)/usage(s){{{0(+x) culinaire(s) : les fruits sont consommés crus et utilisés dans les gelées et confitures ; ils sont également utilisés dans les légumes et plats salés{{{0(+x). Les fruits sont consommés crus et utilisés dans les gelées et les conserves. Ils sont également utilisés dans les plats de légumes et salés néant, inconnus ou indéterminés.néant, inconnus ou indéterminés. Autres infos : dont infos de "FOOD PLANTS INTERNATIONAL" : Distribution : C'est une plante tropicale{{{0(+x) (traduction automatique). Original : It is a tropical plant{{{0(+x). -

Annona Cherimola Mill.) and Highland Papayas (Vasconcellea Spp.) in Ecuador

Faculteit Landbouwkundige en Toegepaste Biologische Wetenschappen Academiejaar 2001 – 2002 DISTRIBUTION AND POTENTIAL OF CHERIMOYA (ANNONA CHERIMOLA MILL.) AND HIGHLAND PAPAYAS (VASCONCELLEA SPP.) IN ECUADOR VERSPREIDING EN POTENTIEEL VAN CHERIMOYA (ANNONA CHERIMOLA MILL.) EN HOOGLANDPAPAJA’S (VASCONCELLEA SPP.) IN ECUADOR ir. Xavier SCHELDEMAN Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor (Ph.D.) in Applied Biological Sciences Proefschrift voorgedragen tot het behalen van de graad van Doctor in de Toegepaste Biologische Wetenschappen Op gezag van Rector: Prof. dr. A. DE LEENHEER Decaan: Promotor: Prof. dr. ir. O. VAN CLEEMPUT Prof. dr. ir. P. VAN DAMME The author and the promotor give authorisation to consult and to copy parts of this work for personal use only. Any other use is limited by Laws of Copyright. Permission to reproduce any material contained in this work should be obtained from the author. De auteur en de promotor geven de toelating dit doctoraatswerk voor consultatie beschikbaar te stellen en delen ervan te kopiëren voor persoonlijk gebruik. Elk ander gebruik valt onder de beperkingen van het auteursrecht, in het bijzonder met betrekking tot de verplichting uitdrukkelijk de bron vermelden bij het aanhalen van de resultaten uit dit werk. Prof. dr. ir. P. Van Damme X. Scheldeman Promotor Author Faculty of Agricultural and Applied Biological Sciences Department Plant Production Laboratory of Tropical and Subtropical Agronomy and Ethnobotany Coupure links 653 B-9000 Ghent Belgium Acknowledgements __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Acknowledgements After two years of reading, data processing, writing and correcting, this Ph.D. thesis is finally born. Like Veerle’s pregnancy of our two children, born during this same period, it had its hard moments relieved luckily enough with pleasant ones. -

Biologist 2 Final 2013

ISSN Versión Impresa 1816-0719 ISSN Versión en linea 1994-9073 ISSN Versión CD ROM 1994-9081 The Biologist (Lima) ORIGINAL ARTICLE /ARTÍCULO ORIGINAL REINTRODUCTION OF THREE PLANT SPECIES IN “EL AGUSTINO” HILL, LIMA – PERU REINTRODUCCIÓN DE TRES ESPECIES DE PLANTAS EN EL CERRO “EL AGUSTINO”, LIMA – PERÚ Rafael La Rosa, Nelly Canto, Adelina Castillo & Mey-Ling Espinoza Laboratorio de Ecofisiología Vegetal. Facultad de Ciencias Naturales y Matemática. Universidad Nacional Federico Villarreal. Calle Río Chepén s/n, El Agustino. Lima, Perú. Telefax 51-1-3623388 Correo electrónico: [email protected] The Biologist (Lima), 2013, 11(2), jul-dec: 185-192. ABSTRACT Fragile ecosystems, like the coastal hills of Lima, suffer a strong impact because of urban development, provokes great damage in the vegetation from radical changes in rainwater and changes in soil composition, resulting in the removal of natural vegetation of these environments. For this reasons we tried to restore the ecosystem in the hill ecosystem “El Agustino” through reforestation with shrubs (Vasconcellea candicans (A. Gray) A. DC. 1864 “mito”) and trees species (Caesalpinia spinosa (Molina) Kuntze 1898 “tara” and Sapindus saponaria L.1753 “choloque”) that lived in this place. In November 2010 it was noted that the two tree species found were transplanted, with the best adapted to the stress conditions of the hill " El Agustino " is C. spinosa, having 90% of individuals growing smoothly, while 95% of individuals of S. saponaria had wilt symptoms of wilting from water deficiency; on the other hand, V. candicans is the other species that apparently has responded to transplantation (100% of individuals), although for this period it was observed defoliated and its vegetative parts defoliated and kept alive (green). -

Redalyc."Status" De Conservación De Las Especies Vegetales Silvestres De

Ecología Aplicada ISSN: 1726-2216 [email protected] Universidad Nacional Agraria La Molina Perú Cruz Silva, Horacio de la; Zevallos Pollito, Percy A.; Vilcapoma Segovia, Graciela "Status" de conservación de las especies vegetales silvestres de uso tradicional en la Provincia de Canta, Lima-Perú. Ecología Aplicada, vol. 4, núm. 1-2, diciembre, 2005, pp. 9-16 Universidad Nacional Agraria La Molina Lima, Perú Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=34100202 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto Ecología Aplicada, 4(1,2), 2005 Presentado: 03/11/2005 ISSN 1726-2216 Aceptado: 05/11/2005 Depósito legal 2002-5474 © Departamento Académico de Biología, Universidad Nacional Agraria La Molina, Lima – Perú. “STATUS” DE CONSERVACIÓN DE LAS ESPECIES VEGETALES SILVESTRES DE USO TRADICIONAL EN LA PROVINCIA DE CANTA, LIMA–PERÚ CONSERVATION "STATUS" OF THE WILD VEGETAL SPECIES OF TRADITIONAL USE IN THE PROVINCE OF CANTA, LIMA-PERU Horacio De la Cruz Silva1, Percy A. Zevallos Pollito2 y Graciela Vilcapoma Segovia3 Resumen Se determinó el status de conservación de 104 especies de uso tradicional de la provincia de Canta-Lima. El estudio se desarrollo en los años de 2003, 2004 y 2005, siguiendo la metodología del CDC (1991) y UICN (1998 & 2002) modificadas para las condiciones de la región y del Perú. Las variables tomadas en consideración fueron: distribución geográfica, abundancia, antigüedad de colecciones, localización en áreas expuestas extrativismo, endemismo, confinamiento, presencia en unidades de conservación y protección in situ. -

Medicinal Flora Consumption in Peru

Ecosystems and Sustainable Development XI 173 MEDICINAL FLORA CONSUMPTION IN PERU ISABEL MARIA MADALENO The National Museum of Natural History and Science, University of Lisbon, Portugal ABSTRACT The current submission is the sequel of a Latin American project on the issue of medicinal flora growth, trade and consumption that was initiated about two decades ago, in 1997. The aim of the research is threefold: i) to offer information about medicinal plant species from tropical environments; ii) to describe best practices in urban and peri-urban sustainable agriculture and forest management projects; and iii) to improve research about the learning processes and fair use of medicinal flora natural resources. Methodology includes an archival investigation into the areas under scrutiny in early colonization times, so as to compare landscape descriptions from the 16th to the 18th century, as well as the use of plant species as food, fuel and for therapeutic applications, with the surveys conducted in our days. The study is a tale of two cities, field researched with a ten-year interval. The first one is Lima, the capital of Peru, within which 8 million metropolitan agglomerations included the port city of Callao in 2006. The second city is Piura, an urban centre of 1,844,100 inhabitants, explored in 2016. Results show an increase in medicinal flora consumption and trade, top ranking chamomile in both urban samples, a surprising fidelity in ten years and two different cities. As to environmental conservation and sustainable practices, results show that species named by the Inca Garcilaso de la Vega, and Antonio Ulloa in the 16th and 18th centuries are still available; this gives us hope that the trend of exploitation is sustainable. -

Universidad Nacional Del Centro Del Peru

UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL DEL CENTRO DEL PERU FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS FORESTALES Y DEL AMBIENTE "COMPOSICIÓN FLORÍSTICA Y ESTADO DE CONSERVACIÓN DE LOS BOSQUES DE Kageneckia lanceolata Ruiz & Pav. Y Escallonia myrtilloides L.f. EN LA RESERVA PAISAJÍSTICA NOR YAUYOS COCHAS" TESIS PARA OPTAR EL TÍTULO PROFESIONAL DE INGENIERO FORESTAL Y AMBIENTAL Bach. CARLOS MICHEL ROMERO CARBAJAL Bach. DELY LUZ RAMOS POCOMUCHA HUANCAYO – JUNÍN – PERÚ JULIO – 2009 A mis padres Florencio Ramos y Leonarda Pocomucha, por su constante apoyo y guía en mi carrera profesional. DELY A mi familia Héctor Romero, Eva Carbajal y Milton R.C., por su ejemplo de voluntad, afecto y amistad. CARLOS ÍNDICE AGRADECIMIENTOS .................................................................................. i RESUMEN .................................................................................................. ii I. INTRODUCCIÓN ........................................................................... 1 II. REVISIÓN BIBLIOGRÁFICA ........................................................... 3 2.1. Bosques Andinos ........................................................................ 3 2.2. Formación Vegetal ...................................................................... 7 2.3. Composición Florística ................................................................ 8 2.4. Indicadores de Diversidad ......................................................... 10 2.5. Biología de la Conservación...................................................... 12 2.6. Estado de Conservación -

UNIVERSIDAD DE CUENCA Facultad De Ciencias Agropecuarias

UNIVERSIDAD DE CUENCA Facultad de Ciencias Agropecuarias Carrera de Ingeniería Agronómica “Evaluación de la germinación y la resistencia de Vasconcelleas silvestres a Fusarium spp como una alternativa de porta injertos para la producción de (Vasconcellea × heilbornii) cv babaco” Trabajo de titulación previo a la obtención del título de Ingeniero Agrónomo AUTORES: Edwin Patricio Parra Tenesaca C.I. 0106620966 Edisson Vladimir Tigre Tigre C.I. 0104107792 DIRECTORA: Msc. Denisse Fabiola Peña Tapia C.I. 0102501809 CUENCA-ECUADOR 06/06/2019 UNIVERSIDAD DE CUENCA RESUMEN El género Vasconcellea es considerado el más importante de la familia Caricaceae, con 12 especies silvestres reportadas en el Austro ecuatoriano, que podrían ser consideradas como potenciales portainjertos para babaco (V. x heilbornii) a fin de controlar la susceptibilidad al hongo del género Fusarium. El problema que presentan las especies silvestres es el bajo porcentaje de germinación a nivel de campo, en este estudio se evaluó la germinación in vitro de embriones de Vasconcelleas silvestres (V. candicans, V. stipulata y V. cundinamarcensis) a Fusarium spp. Se utilizó un diseño completamente al azar (DCA), con 12 tratamientos (3 especies de Vasconcelleas x 4 dosis de ácido giberélico) y 10 repeticiones. En la germinación de embriones, la especie V. cundinamarcensis, obtuvo el mejor resultado con un 28,75%, teniendo una relación directamente proporcional a la evaluación de la viabilidad con un 44%. El uso de AG3 no estimuló la germinación, por el contrario, tuvo una relación inversamente proporcional a la concentración de la fitohormona. Respecto a la resistencia al patógeno, no se observó sintomatología de la enfermedad en las especies silvestres ni en el control de susceptibilidad (babaco) luego de los 60 días de la inoculación.