Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mothers Grimm Kindle

MOTHERS GRIMM PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Danielle Wood | 224 pages | 01 Oct 2016 | Allen & Unwin | 9781741756746 | English | St Leonards, Australia Mothers Grimm PDF Book Showing An aquatic reptilian-like creature that is an exceptional swimmer. They have a temper that they control and release to become effective killers, particularly when a matter involves a family member or loved one. She took Nick to Weston's car and told Nick that he knew Adalind was upstairs with Renard, and the two guys Weston sent around back knew too. When Wu asks how she got over thinking it was real, she tells him that it didn't matter whether it was real, what mattered was losing her fear of it. Dick Award Nominee I found the characters appealing, and the plot intriguing. This wesen is portrayed as the mythological basis for the Three Little Pigs. The tales are very dark, and while the central theme is motherhood, the stories are truly about womanhood, and society's unrealistic and unfair expectations of all of us. Paperback , pages. The series presents them as the mythological basis for The Story of the Three Bears. In a phone call, his parents called him Monroe, seeming to indicate that it is his first name. The first edition contained 86 stories, and by the seventh edition in , had unique fairy tales. Danielle is currently teaching creative writing at the University of Tasmania. The kiss of a musai secretes a psychotropic substance that causes obsessive infatuation. View all 3 comments. He asks Sean Renard, a police captain, to endorse him so he would be elected for the mayor position. -

The Brothers Grimm and the Yearning for Home Maureen Clack University of Wollongong

University of Wollongong Thesis Collections University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Year Returning to the Scene of the Crime: The Brothers Grimm and the Yearning for Home Maureen Clack University of Wollongong Clack, Maureen, Returning to the Scene of the Crime: The Brothers Grimm and the Yearning for Home, M.A. thesis, School of Journalism and Creative Writing, University of Wollongong, 2006. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/730 This paper is posted at Research Online. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/730 RETURNING TO THE SCENE OF THE CRIME: THE BROTHERS GRIMM AND THE YEARNING FOR HOME A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree MASTER OF ARTS (HONOURS) from UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG by MAUREEN CLACK, BACHELOR OF ARTS (HONOURS) FACULTY OF CREATIVE ARTS 2006 CERTIFICATION I, Maureen Clack, declare that this thesis, submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Master of Arts (Honours), in the Faculty of Creative Arts, University of Wollongong, is wholly my own work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. The document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. Maureen Clack 31 October 2006 CONTENTS LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Page viii INTRODUCTION Fairy Tales, Feminism, Forensic Science and Home 1 CHAPTER 1 Feminism v Fairy Tales 17 CHAPTER 2 Returning to the Scene of the Crime 37 Visual Artists and Childhood Trauma 43 Hansel and Gretel: A Forensic Analysis 67 CHAPTER 3 Home Sweet Home 73 Visual Artists and Memories of Home 95 CHAPTER 4 Defective Stories 111 CONCLUSION 153 LIST OF WORKS CITED 159 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Throughout the lengthy process of constructing the argument and the artworks that make up this thesis I have had generous support from the following members of staff in the Faculty of Creative Arts. -

Naturalism, the New Journalism, and the Tradition of the Modern American Fact-Based Homicide Novel

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. U·M·I University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml48106-1346 USA 3131761-4700 800!521-0600 Order Number 9406702 Naturalism, the new journalism, and the tradition of the modern American fact-based homicide novel Whited, Lana Ann, Ph.D. -

The Tales of the Grimm Brothers in Colombia: Introduction, Dissemination, and Reception

Wayne State University Wayne State University Dissertations 1-1-2012 The alest of the grimm brothers in colombia: introduction, dissemination, and reception Alexandra Michaelis-Vultorius Wayne State University, Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations Part of the German Literature Commons, and the Modern Languages Commons Recommended Citation Michaelis-Vultorius, Alexandra, "The alet s of the grimm brothers in colombia: introduction, dissemination, and reception" (2012). Wayne State University Dissertations. Paper 386. This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wayne State University Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@WayneState. THE TALES OF THE GRIMM BROTHERS IN COLOMBIA: INTRODUCTION, DISSEMINATION, AND RECEPTION by ALEXANDRA MICHAELIS-VULTORIUS DISSERTATION Submitted to the Graduate School of Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY 2011 MAJOR: MODERN LANGUAGES (German Studies) Approved by: __________________________________ Advisor Date __________________________________ __________________________________ __________________________________ __________________________________ © COPYRIGHT BY ALEXANDRA MICHAELIS-VULTORIUS 2011 All Rights Reserved DEDICATION To my parents, Lucio and Clemencia, for your unconditional love and support, for instilling in me the joy of learning, and for believing in happy endings. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This journey with the Brothers Grimm was made possible through the valuable help, expertise, and kindness of a great number of people. First and foremost I want to thank my advisor and mentor, Professor Don Haase. You have been a wonderful teacher and a great inspiration for me over the past years. I am deeply grateful for your insight, guidance, dedication, and infinite patience throughout the writing of this dissertation. -

Classification of Animals

Grade 3 Core Knowledge Language Arts® • Listening & Learning™ Strand Classification of Animals of Classification Tell It Again!™ Read-Aloud Anthology Read-Aloud Again!™ It Tell Classification of Animals Tell It Again!™ Read-Aloud Anthology Listening & Learning™ Strand GrAde 3 Core Knowledge Language Arts® Creative Commons Licensing This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. You are free: to Share — to copy, distribute and transmit the work to Remix — to adapt the work Under the following conditions: Attribution — You must attribute the work in the following manner: This work is based on an original work of the Core Knowledge® Foundation made available through licensing under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. This does not in any way imply that the Core Knowledge Foundation endorses this work. Noncommercial — You may not use this work for commercial purposes. Share Alike — If you alter, transform, or build upon this work, you may distribute the resulting work only under the same or similar license to this one. With the understanding that: For any reuse or distribution, you must make clear to others the license terms of this work. The best way to do this is with a link to this web page: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/ Copyright © 2013 Core Knowledge Foundation www.coreknowledge.org All Rights Reserved. Core Knowledge Language Arts, Listening & Learning, and Tell It Again! are trademarks of the Core Knowledge Foundation. Trademarks and trade names are shown in this book strictly for illustrative and educational purposes and are the property of their respective owners. -

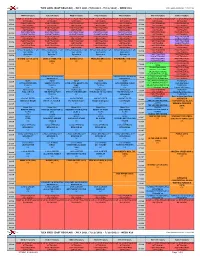

TLEX GRID (EAST REGULAR) - JULY 2021 (7/5/2021 - 7/11/2021) - WEEK #28 Date Updated:6/25/2021 11:36:51 AM

TLEX GRID (EAST REGULAR) - JULY 2021 (7/5/2021 - 7/11/2021) - WEEK #28 Date Updated:6/25/2021 11:36:51 AM MON (7/5/2021) TUE (7/6/2021) WED (7/7/2021) THU (7/8/2021) FRI (7/9/2021) SAT (7/10/2021) SUN (7/11/2021) SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM 05:00A 05:00A NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 05:30A 05:30A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 06:00A 06:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 06:30A 06:30A (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 07:00A 07:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 07:30A 07:30A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 08:00A 08:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) RIPLEY'S BELIEVE IT OR RIPLEY'S BELIEVE IT OR -

![Introduction ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3885/introduction-3563885.webp)

Introduction ]

[Introduction ] Old wine is often all the better for being re- bottled; perhaps old wives’ tales are like that, too. —Big Claus and Little Claus How do you breathe new life into forms considered archaic, dated, passé, old- fashioned, or, worse yet, obsolete? Peter Davies set himself that challenge when he published The Fairies Return, an anthology described on its dust jacket as a “Christmas book written by a number of distinguished authors. It is a collection of well- known fairy stories retold for grownups in a modern setting.” Moving the tales from times past, from the nursery to the parlor, and transforming the wondrous into the quotidian (and vice versa) was a chal- lenge he issued to “several hands”—fifteen contemporaries, most of them on familiar terrain when it came to fairies and folklore. Together, they created a rich mosaic, with each vi- brant tile telling us as much about Great Britain in the era [ 1 ] following World War I as about the culture from which it was drawn. The Fairies Return offers sophisticated fare for adults rather than primal entertainment for children. Moving in a satirical mode, it delivers on the promise of what “satire” originally meant: satura, or a mixture of different things blended to suit discerning tastes.1 Not only do we have a vari- 2] ety of tales drawn from Denmark, Germany, France, and the Orient (in addition to England), but we also have authors who choose targets that include evils ranging from preda- tory behavior and political corruption to drug addiction and social ambition. -

Annual Recorders of the Past

VOLUME 22 ∙ NO 1 ∙ ApriL 2014 MAGAZINE ANNUAL RECORDERS OF THE PAST EDITORS Bernd Zolitschka, Jennifer pike, Lucien von Gunten and Thorsten Kiefer MINI SECTION Human impact on soils and sediments in Asia 2 ANNOUNCEMENTS News Calendar 2nd PAGES Solar Forcing Workshop A new look and a new name 20-23 May 2014 - Davos, Switzerland Following our review of 20 years of PAGES news in the last issue, we realized, based on 3rd Asia 2k Workshop our track record, that a facelift was overdue. But this time we’ve gone even further and 26-27 May 2014 - Beijing, China we’ve also changed the name to Past Global Changes Magazine, or PAGES Magazine for short. We believe that this more accurately reflects PAGES news’ evolution in recent years 3rd Sea Ice Proxy Working Group meeting from a simple newsletter into more of a magazine-style publication. We also hope that 23-25 June 2014 - Bremerhaven, Germany our new look magazine, with its more descriptive title, will attract a broader audience. North America 2k - Phase 2 SSC Meeting in Paris 23-27 June 2014 - Fort Collins, USA pAGES’ Scientific Steering Committee (SSC) met in paris in January 2014. in addition Australasia 2k Working Group workshop to approving four new Working Groups, the SSC also reviewed Working Group annual 26-27 June 2014 - Melbourne, Australia reports, met with Future Earth representatives and discussed pAGES’ strategic direction in the coming year. The article on the opposite page gives an overview of the ongoing LOTRED-SA 3rd symposium and training course developments. The meeting was preceded by a day-long symposium featuring research 07-12 July 2014 - Medellín, Colombia talks by pAGES SSC members and a range of parisian paleo-scientists. -

Penguin Classics

PENGUIN CLASSICS A Complete Annotated Listing www.penguinclassics.com PUBLISHER’S NOTE For more than seventy years, Penguin has been the leading publisher of classic literature in the English-speaking world, providing readers with a library of the best works from around the world, throughout history, and across genres and disciplines. We focus on bringing together the best of the past and the future, using cutting-edge design and production as well as embracing the digital age to create unforgettable editions of treasured literature. Penguin Classics is timeless and trend-setting. Whether you love our signature black- spine series, our Penguin Classics Deluxe Editions, or our eBooks, we bring the writer to the reader in every format available. With this catalog—which provides complete, annotated descriptions of all books currently in our Classics series, as well as those in the Pelican Shakespeare series—we celebrate our entire list and the illustrious history behind it and continue to uphold our established standards of excellence with exciting new releases. From acclaimed new translations of Herodotus and the I Ching to the existential horrors of contemporary master Thomas Ligotti, from a trove of rediscovered fairytales translated for the first time in The Turnip Princess to the ethically ambiguous military exploits of Jean Lartéguy’s The Centurions, there are classics here to educate, provoke, entertain, and enlighten readers of all interests and inclinations. We hope this catalog will inspire you to pick up that book you’ve always been meaning to read, or one you may not have heard of before. To receive more information about Penguin Classics or to sign up for a newsletter, please visit our Classics Web site at www.penguinclassics.com. -

A Qualitative Examination of Fairy-Tales and Women's Intimate

Enchanted: A Qualitative Examination of Fairy-Tales and Women’s Intimate Relational Patterns A dissertation presented to the faculty of ANTIOCH UNIVERSITY SANTA BARBARA in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PSYCHOLOGY in CLINICAL PSYCHOLOGY By Amanda Schnibben 05/2014 Enchanted: A Qualitative Examination of Fairy-Tales and Women’s Intimate Relational Patterns This dissertation, by Amanda Schnibben, has been approved by the committee members signed below who recommend that it be accepted by the faculty of Antioch University Santa Barbara in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PSYCHOLOGY Dissertation Committee: ____________________________________ Juliet Rohde-Brown, Ph.D. Chairperson ____________________________________ Salvador Trevino, Ph.D. Second Faculty ____________________________________ Melissa Jones-Cantekin, Ph.D. External Expert ____________________________________ Courtney Keene-Viscomi Student Reader ii Copyright © 2014 by Amanda Schnibben All rights reserved iii Abstract Fairy-tales and myth have long been held as ways of communicating what is happening in society and within a culture. This dissertation study examined the interview narratives of 10 women regarding the impact of fairy-tales and myth on female identity in the context of intimate relationship patterns. This study utilized definitions of fairy-tale and myth derived from Biechonski’s (2005) framework, while augmenting these conceptualizations with depth psychology perspectives. The study’s findings were produced using qualitative, phenomenological research methods (Merriam, 2009). Results of the study demonstrated that some of the female participants identified with fairy-tales during their youth; however, all participants indicated that real life is far more challenging when contrasted with typical Western fairy-tale stories that often portray an easeful outcome to engagement in a romantic relationship. -

By JIMI BERNATH

BARDO FILMS CINEMA OF THE AFTERLIFE by JIMI BERNATH 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction “Carnival of Souls” : Familiar Nightmares …………………………………………………..………...43 Bardo Blockbusters : “American Beauty” & “The Sixth Sense” ……………….……...…..85 “Jacob’s Ladder” : Search for a Guide ……………………………………………………..………….102 “Enter the Void” : Escape Velocity …………………………………………………………..…………. 49 The Dharma of Lynch: “Mulholland Drive” & “Inland Empire” ……………….……….108 “Vera” : The Underworld ………………………………………………………………………..…...……….106 Escape from Hell : “Diamonds of the Night” …………………………………………….………. 26 “Le Quattro Volte” : Elemental Change ……………………………………………………..…………..7 “Beetlejuice” : Guide as Huckster …………………………………………………………….…………..78 “Defending Your Life” : Purgatory as Shtick …………………………………………….…………90 “Ink” : Remembering Who You Were …………………………………………………………….…….59 “The Bothersome Man” : Not Bad As Purgatories Go …………………………….………….64 “The Lovely Bones” : Avenging Angel …………………………………………………………….….55 Following Robin : “Being Human” & “What Dreams May Come” …………………...22 Following Downey : “Chances Are” & “Hearts and Souls” ………………………………..46 Death at an Early Age : “Donnie Darko” & “Wristcutters a Love Story” ………….94 “Samaritan Girl” : Saint or Sinner ……………………………………………………………………..126 “The Life Before Her Eyes” : Headline Bardo ……………………………………………….…….75 Dia de Muertos : “Macario” “The Book of Life” & “Coco” …………………………..……..9 “Waking Life” : All Our Guides …………………………………………………………………….……...68 Japanese Ghost Stories : “Pitfall” & “Kuroneko” ……………………….…………….………..29 Crossing the Big -

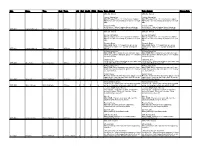

Current Change Date AFF-001 Captain Marvel Main Char

blac Name Type Cost Team Atk Def Health Flight Range Text - Original Text - Current Change Date AKA Ms. Marvel AKA Ms. Marvel Energy Absorption Energy Absorption Main [Energy]: Put a +1/+1 counter on Captain Main [Energy]: Put a +1/+1 counter on Captain Marvel for each other [ranged] character on your Marvel for each other [ranged] character on your side. side. Woman of War Woman of War Level Up (4) - When Captain Marvel stuns an Level Up (4) - When Captain Marvel stuns an AFF-001 Captain Marvel Main Character A-Force 2 4 6 x x enemy character in combat, she gains an XP. enemy character in combat, she gains an XP. AKA Ms. Marvel AKA Ms. Marvel Energy Absorption Energy Absorption Main [Energy]: Put a +1/+1 counter on Captain Main [Energy]: Put a +1/+1 counter on Captain Marvel for each other [ranged] character on your Marvel for each other [ranged] character on your side. side. Photonic Blast Photonic Blast Main [Skill]: Put a -1/-1 counter on an enemy Main [Skill]: Put a -1/-1 counter on an enemy character for each +1/+1 counter on Captain character for each +1/+1 counter on Captain AFF-002 Captain Marvel Main Character A-Force 4 6 6 x x Marvel. Marvel. A-Force Assemble! A-Force Assemble! Main [Skill]: When characters on your side team Main [Skill]: When characters on your side team attack the next time this turn, put a +1/+1 counter attack the next time this turn, put a +1/+1 counter on each of them.