The Pogroms of 1881 As a Part of the Historians' Personal Experience and As a Building Block of the Collective Memory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fulfillmenttheep008764mbp.Pdf

FULFILLMENT ^^^Mi^^if" 41" THhODOR HERZL FULFILLMENT: THE EPIC STORY OF ZIONISM BY RUFUS LEARSI The World Publishing Company CLEVELAND AND NEW YORK Published by The World Publishing Company FIRST EDITION HC 1051 Copyright 1951 by Rufus Learsi All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the publisher, except for brief passages included in a review appearing in a newspaper or magazine. Manufactured in the United States of America. Design and Typography by Jos. Trautwein. TO ALBENA my wife, who had no small part in the making of this book be'a-havah rabbah FOREWORD MODERN or political Zionism began in 1897 when Theodor Herzl con- vened the First Zionist Congress and reached its culmination in 1948 when the State of Israel was born. In the half century of its career it rose from a parochial enterprise to a conspicuous place on the inter- national arena. History will be explored in vain for a national effort with roots imbedded in a remoter past or charged with more drama and world significance. Something of its uniqueness and grandeur will, the author hopes, flow out to the reader from the pages of this narrative. As a repository of events this book is not as inclusive as the author would have wished, nor does it make mention of all those who labored gallantly for the Zionist cause across the world and in Pal- estine. Within the compass allotted for this work, only the more significant events could be included, and the author can only crave forgiveness from the actors living and dead whose names have been omitted or whose roles have perhaps been understated. -

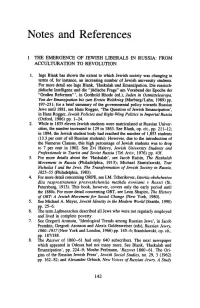

Notes and References

Notes and References THE EMERGENCE OF JEWISH LIBERALS IN RUSSIA: FROM ACCULTURATION TO REVOLUTION 1. Inge Blank has shown the extent to which Jewish society was changing in terms of, for instance, an increasing number of Jewish university students. For more detail see Inge Blank, 'Haskalah und Emanzipation. Die russisch jUdische Intelligenz und die "jUdische Frage" am Vorabend der Epoche der "GraBen Reformen"', in Gotthold Rhode (ed.), Juden in Ostmitteleuropa. Von der Emantipatton bis zum Ersten Weltkrieg (Marburg/Lahn, 1989) pp. 197-231; for a brief summary of the governmental policy towards Russian Jews until 1881, see Hans Rogger, 'The Question of Jewish Emancipation', in Hans Rogger, Jewish Policies and Right-Wing Politics in Imperial Russia (Oxford, 1986) pp. 1-24. 2. While in 1835 eleven Jewish students were matriculated at Russian Univer sities, the number increased to 129 in 1863. See Blank, op. cit., pp. 211-12; in 1894, the Jewish student body had reached the number of 1,853 students (13.3 per cent of all Russian students). However, due to the introduction of the Numerus Clausus, this high percentage of Jewish students was to drop to 7 per cent in 1902. See Zvi Halevy, Jewish University Students and Professionals in Tsarist and Soviet Russia (Tel Aviv, 1976) pp. 43f. 3. For more details about the 'Haskalah', see Jacob Raisin, The Haskalah Movement in Russia (Philadelphia, 1913); Michael Stanislawski, Tsar Nicholas I and the Jews. The Transformation of Jewish Society in Russia, 1825-55 (philadelphia. 1983). 4. For more detail concerning ORPE, see I.M. Tcherikover, Istoriia obshchestva dlia rasprostranenie prosvesh cheniia mezhdu evreiami v Rossii (St. -

Traduceri În Limba Română Din Literatura Clasică Idiş

sincronizare durabilitate FONDUL SOCIAL EUROPEAN Investeşte în Modele culturale OAMENI EUROPENE Traduceri în limba română din literatura clasică idiş Autor: Marioara-Camelia N. CRĂCIUN Lucrare realizată în cadrul proiectului "Cultura română şi modele culturale europene - cercetare, sincronizare, durabilitate", cofinanţat din FONDUL SOCIAL EUROPEAN prin Programul Operaţional Sectorial pentru Dezvoltarea Resurselor Umane 2007 – 2013, Contract nr. POSDRU/159/1.5/S/136077. Titlurile şi drepturile de proprietate intelectuală şi industrial ă asupra rezultatelor obţinute în cadrul stagiului de cercetare postdoctorală aparţinAcademiei Române. * * * Punctele de vedere exprimate în lucrare aparţin autorului şi nu angajează Comisia Europeană şi Academia Română, beneficiara proiectului. DTP, complexul editorial/ redacţional, traducerea şi corectura aparţin autorului. Descărcare gratuită pentru uz personal, în scopuri didactice sau ştiinţifice. Reproducerea publică, fie şi parţială şi pe orice suport, este posibilă numai cu acordul prealabil al Academiei Române. ISBN 978-973-167-303-5 CUPRINS Rezumat (în engleză)..............................................................................................4 Rezumat (în română) .............................................................................................6 Introducere. Locul culturii idiș în spaţiul românesc ............................................8 Cap. I. Traducerile din literatura clasică idiș. O perspectivă diacronică .......................17 I.1. Începuturi .......................................................................................................23 -

The Legacy of Jewish-Russian Literature

General Introduction: The Legacy of Jewish-Russian Literature By Maxim D. Shrayer DUAL LITERARY IDENTITIES What are cultures measured by? Cultural contributions are difficult to quantify and even harder to qualify without a critical judgment in hand. In the case of verbal arts, and of literature specifically, various criteria of formal perfection and originality, significance in literary history, and aspects of time, place, and milieu all contribute to the ways in which one regards a writer’s contribution. In the case of Jewish culture in Diaspora, and specifically of Jewish writing created in non-Jewish languages adopted by Jews, the reckoning of a writer’s status is riddled with a set of powerful contrapositions. Above all else, there is the duality, or multiplicity, of a writer’s own iden- tity—both Jewish and German (Heinrich Heine) or French (Marcel Proust) or Russian (Isaac Babel) or Polish (Julian Tuwim) or Hungarian (Imre Kertész) or Brazilian (Clarice Lispector) or Canadian (Mordechai Richler) or American (Bernard Malamud). Then there is the dividedly redoubled perspec- tive of a Diasporic Jew: both an in-looking outsider and an out-looking insider. And there is the language of writing itself, not always one of the writer’s native setting, not necessarily one in which a writer spoke to his or her own parents or non-Jewish childhood friends, but in some cases a second or third or forth language—acquired, mastered, and made one’s own in a flight from home.1 Evgeny Shklyar (1894–1942), a Jewish-Russian poet and a Lithuanian patriot who translated into Russian the text of the Lithuanian national anthem 1 In the context of Jewish-Russian history and culture, the juxtaposition between a “divided” and a “redoubled” identity goes back to the writings of the critic and polemicist Iosif Bikerman (1867–1941? 1942?), who stated in 1910, on the pages of the St. -

TELFED F APRIL 1997 VOL

w estublishecl 1948 TELFED f APRIL 1997 VOL. 23 NO. 1 A SOUTH AFRICAN ZIONIST FEDERATION (ISRAEL) PUBLICATION THE ROri^ABOUT O^E iSOUTH 6 UP C l o a k a n d , Dagger at Beit Berl. Lithuanian I Family Reunion | m a m i Rabbis and Politics Bookstore Findings i 46 SOKOLOV (2nd Floor) RAMAT-HASHARON Tel. 03-5400070 Home 09-446967 F a x 0 3 - 5 4 0 0 0 7 7 April 1997 D e a r F r i e n d s , I have just returned from the I.T.B. (International Travel Fair) in Berlin, and had a great chance to see the "world" on show in six huge halls where I managed to pick up quite a few new ideas and destinations. I was also amazed at Berlin which is certainly one of the most exciting cities in Europe today. The blending of the old and new as well as the great Museums and Galleries really put Berlin on par with Paris, London, Rome and Prague. Carol and I decided to go back to South Africa for a eight-day vacation and chose to concentrate only on the Cape and Garden Route. Our plan was to spend two days in Knysna, 2 in Piettenberg and the rest in Stellenbosch and Cape Town. After an excellent SAA flight, we carried on directly to George and drove to our small (8-room) bed and breakfast lodge on Leisure Island overlooking the Heads and Featherbed Nature Reserve in Knysna. We were captivated and decided to cancel the last three days and to stay on in the Garden Route. -

Fine Judaica, to Be Held March 19Th, 2015

F i n e J u d a i C a . booKs, manusCripts, autograph Letters, CeremoniaL obJeCts, maps & graphiC art K e s t e n b au m & C om pa n y thursday, m a rCh 19th, 2015 K est e n bau m & C o m pa ny . Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art A Lot 8 Catalogue of F i n e J u d a i C a . PRINTED BOOK S, MANUSCRIPTS, AUTOGRAPH LETTERS, CEREMONIAL OBJECTS, MAPS AND GRAPHIC A RT FEATURING: A COllECTION OF HOLY L AND M APS: THE PROPERT Y OF A GENTLEMAN, LONDON JUDAIC A RT FROM THE ESTATE OF THE LATE R AbbI & MRS. A BRAHAM K ARP A MERICAN-JUDAICA: EXCEPTIONAL OffERINGS ——— To be Offered for Sale by Auction, Thursday, 19th March, 2015 at 3:00 pm precisely ——— Viewing Beforehand: Sunday, 15th March - 12:00 pm - 6:00 pm Monday,16th March - 10:00 pm - 6:00 pm Tuesday, 17th March - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm Wednesday, 18th March - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm No Viewing on the Day of Sale This Sale may be referred to as: “Hebron” Sale Number Sixty-Four Illustrated Catalogues: $38 (US) * $45 (Overseas) KestenbauM & CoMpAny Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art . 242 West 30th street, 12th Floor, new york, NY 10001 • tel: 212 366-1197 • Fax: 212 366-1368 e-mail: [email protected] • World Wide Web site: www.Kestenbaum.net K est e n bau m & C o m pa ny . Chairman: Daniel E. Kestenbaum Operations Manager: Jackie S. -

April 1998 Vol 24 No

TELFEP Established 1948 APRIL 1998 VOL 24 NO. 1 A SOUTH AFRICAN ZIONIST FEDERATION (ISRAEL) PUBLICATION THESACAOFASHUL: FROM PA ROW TO RA'ANANA INSIDE: FEATURE: ART SCENE: •Israel Fair •Eiiat: a home to SA dancers •Israel in Lebanon; RELIOION: an intennew with Yossi Beilin •New insights on the Vilna Gaon PEOPLE: NUPTIALS, •Avraham Infeld: a trip for every youngster COMMUNITY NEWS •Israeli police play tennis in SA AND MORE.... •Avril Shulman: talking pretty 46 SOKOLOV (2nd Floor) RAMAT-HASHARON Tel. 03-5488111 Home 09-7446967 F a x 0 3 - 5 4 0 0 0 7 7 Dear Friends, They talk about a mitim (depression), but as I sit here in my office, I'm battling to get seats on aircraft for our regular passengers. It looks like there will be many people left at home this year - mainly those who didn't book in advance. After the great success of last year, we are proud to announce that we are again operating 2 special tours for music lovers which will be led by Brenda Miller. ^Russia - 19/5 - 2/6 ^Prague - 19/6 - 26/6 We have a few seats left on these tours (not many). Please call Ifat or Ilanit for a detailed Itinerary and registration form. In February, Carol and I went for the 2nd year running to the Cape, absolutely beautiful - Hog-Hollow outside Plettenberg. The Tides - a bed and breakfast in Plettenberg - 40 dollars per night! Leisure Island in Knysna - The Lanzerac in Paarl - wow! What a place and then we discovered a beautiful new B/B in Cape Town on the sea - a real find. -

Kiev, Jewish Metropolis Limns the History of Kiev Jewry from the Official Readmis- Sion of Jews to the City in 1859 to the Outbreak of World War I

JUDAICA • RUSSIA & EASTerN EUROPE meir Jewish life in late imperial Kiev “A multidimensional and panoramic picture of Jewish v e i K communal life in late Tsarist Kiev. The book is meticulously K i e v researched, eminently readable, and rich in detail.” —Jeffrey Veidlinger, jewish author of Jewish Public Culture in the Late Russian Empire jewish metropolis Populated by urbane Jewish merchants and professionals as well as new arrivals from A HISTORY, 1859 –1914 the shtetl, imperial Kiev was acclaimed for its opportunities for education, culture, employment, and entrepreneurship but cursed for the often pitiless persecution of its Jews. Kiev, Jewish Metropolis limns the history of Kiev Jewry from the official readmis- sion of Jews to the city in 1859 to the outbreak of World War I. It explores the Jewish community’s politics, its leadership struggles, socioeconomic and demographic shifts, religious and cultural sensibilities, and relations with the city’s Christian population. metropolis Drawing on archival documents, the local press, memoirs, and belles lettres, Natan M. Meir shows Kiev’s Jews at work, at leisure, in the synagogue, and engaged in the activities of myriad Jewish organizations and philanthropies. NATAN M. MEIR is the Lorry I. Lokey Professor of Judaic Studies at Portland State University in Portland, Oregon. The Modern Jewish experience Paula Hyman and Deborah Dash Moore, editors Cover illustration: Kreshchatik, ca. 1890–1900. Courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division INDIANA University Press Bloomington & Indianapolis www.iupress.indiana.edu INDIANA natan m. meir 1-800-842-6796 Kiev MECH.indd 1 4/8/10 1:40:49 PM Kiev, Jewish Metropolis THE MODERN JEWISH EXPERIENCE Paula Hyman and Deborah Dash Moore, editors k i e v jewish metropolis A HISTORY, 1859 –1914 NataN M. -

An Anthology of Jewish-Russian Literature

An Anthology of Jewish-Russian Literature Two Centuries of Dual Identity in Prose and Poetry Volume 1: 1801—1953 Edited, selected, and cotranslated, with introductory essays by Maxim D. Shrayer cM.E.Sharpe Armonk, New York London, England f CONTENTS Volume 1: 1801-1953 Acknowledgments xiii Note on Transliteration, Spelling of Names, Dates, and Notes xvii Note on How to Use This Anthology xix Editor's General Introduction: Toward a Canon of Jewish-Russian Literature Maxim D. Shrayer xxiii Jewish-Russian Literature: A Selected Bibliography lxi THE BEGINNING Editor's Introduction Maxim D. Shrayer 3 Leyba Nevakhovich (1776-1831) 5 From Lament of the Daughter ofJudah (1803) 7 GAINING A VOICE: 1840-1881 Editor's Introduction Maxim D. Shrayer 13 Leon Mandelstam (1819-1889) 15 "The People" (1840) 17 Afanasy Fet (1820-1890) 20 "When my daydreams cross the brink of long-lost days . (1844) 24 "Sheltered by a crimson awning ..(1847) 25 Ruvim Kulisher (1828-1896) 26 From An Answer to the Slav (1849; pub. 1911) 28 Osip Rabinovich (1817-1869) 33 From The Penal Recruit (1859) 35 Lev Levanda (1835-1888) 44 From Seething Times (1860s; pub. 1871-73) 47 vii Vlll CONTENTS Grigory Bogrov (1825-1885) 60 From Notes of a Jew. "Childhood Sufferings" (1863; pub. 1871-73) 62 FIRST FLOWERING: 1881-1902 Editor's Introduction Maxim D. Shrayer 11 Rashel Khin (1861-1928) 73 From The Misfit (1881) 75 Semyon Nadson (1862-1887) 79 From "The Woman" (1883) 81 "I grew up shunning you, O most degraded nation .. ." (1885) 81 Nikolay Minsky (1855-1937) 83 "To Rubinstein" (1886) 85 Simon Frug (1860-1916) 86 "Song" (1890s) 88 "Shylock" (1890s) 88 "An Admirer of Napoleon" (1800s) 91 Ben-Ami (1854-1932) 95 Author's Preface to Volume 1 of Collected Stories and Sketches (1898) 97 Avraam-Uria Kovner (1842-1909) 100 From Memoirs of a Jew (ca. -

Ivan Franko Und Die Jüdische Frage in Galizien

1 Sonderdruck aus 2 3 4 5 6 7 Alois Woldan / Olaf Terpitz (Hg.) 8 9 10 11 Ivan Franko und die jüdische Frage 12 in Galizien 13 14 15 Interkulturelle Begegnungen und Dynamiken 16 17 im Schaffen des ukrainischen Schriftstellers 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 V&R unipress 35 36 37 Vienna University Press 38 39 ISBN 978-3-8471-0521-3 40 ISBN 978-3-8470-0521-6 (E-Book) 41 ISBN 978-3-7370-0521-0 (V&R eLibrary) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 Inhalt Vorwort . .................................... 7 Roman Mnich (Siedlce) Ivan Franko und das Judentum ........................ 9 Tamara Hundorova (Kiew) Jüdische Akzente in Ivan Frankos Volkstümler-Konzeption ........ 21 Mychajlo Hnatjuk (L’viv) Ivan Franko und das galizische Judentum. Literarischer und publizistischer Kontext ............................ 35 Yaroslav Hrytsak (L’viv) Between Philo-Semitism and Anti-Semitism. The Case of Ivan Franko . 47 George G. Grabowicz (Cambridge, MA) Ivan Franko and the Literary Depiction of Jews. Parsing the Contexts . 59 Alois Woldan (Wien) Jüdische Bilder und Stereotypen in Ivan Frankos „Boryslaver Zyklus“ .. 93 Jevhen Pshenychnyj (Drohobycˇ) Ivan Franko und Hermann Barac. Ein Dialog, der nie stattgefunden hat . 109 Wolf Moskovich (Jerusalem) Two Views on the Problems of Ukrainian-Jewish Relations. Ivan Franko and Vladimir (Zeev) Jabotinsky ........................119 Christoph Augustynowicz (Wien) Blutsauger-Bilder und ihre antijüdischen Implikationen in Galizien . -

Between Babylon and Jerusalem. Selected Writings, Ed

Simon Rawidowicz BETWEEN BABYLON AND JERUSALEM Selected Writings Edited by David N. Myers and Benjamin C. I. Ravid library of jewish history and culture Volume 2 Bibliothek jüdischer Geschichte und Kultur Library of Jewish History and Culture Band / Volume 2 Im Auftrag der Sächsischen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Leipzig On behalf of the Saxonian Academy of Sciences and Humanities at Leipzig herausgegeben / edited von / by Dan Diner Redaktion / editorial staff Marcel Müller Momme Schwarz Franziska Jockenhöfer Markus Kirchhoff Cyra Sommer Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht Simon Rawidowicz Between Babylon and Jerusalem Selected Writings Edited by David N. Myers and Benjamin C. I. Ravid The “Library of Jewish History and Culture” is part of the research project “European Traditions – Encyclopedia of Jewish Cultures” at the Saxonian Academy of Sciences and Humanities at Leipzig. It is sponsored by the Academy program of the Federal Re- public of Germany and the Free State of Saxony. The Academy program is coordinated by the Union of the German Academies of Sciences and Humanities. This volume is co-financed by tax funds on the basis of the budget approved by the Saxon State Parliament. Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek: Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über https://dnb.de abrufbar. © 2020, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, Theaterstraße 13, D-37073 Göttingen Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Das Werk und seine Teile sind urheberrechtlich geschützt. Jede Verwertung in anderen als den gesetzlich zugelassenen Fällen bedarf der vorherigen schriftlichen Einwilligung des Verlages. Satz: textformart, Göttingen | www.text-form-art.de Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht Verlage | www.vandenhoeck-ruprecht-verlage.com ISSN 2197-0904 ISBN (Print) 978-3-525-31125-7 ISBN (PDF) 978-3-666-31125-3 https://doi.org/10.13109/9783666311253 Dieses Material steht unter der Creative-Commons-Lizenz Namensnennung – Nicht kommerziell – Keine Bearbeitungen 4.0 International. -

Haim Nahman Bialik's "In the City of Slaughter" a GREAT JEWISH BOOKS TEACHER WORKSHOP RESOURCE KIT

Haim Nahman Bialik's "In the City of Slaughter" A GREAT JEWISH BOOKS TEACHER WORKSHOP RESOURCE KIT Teachers’ Guide This guide accompanies resources that can be found at: http://www.teachgreatjewishbooks.org/resource-kits/haim-nahman- bialiks-city-slaughter. Introduction “In the City of Slaughter,” written in 1903 in what was then the Russian Empire, is the single most influential Hebrew poem— perhaps the single most influential Jewish literary text—of the twentieth century. It is commonly understood to have had an outsized and lasting effect on how people in the once vast communities of East European Jewry, and later in the new Jewish community of Palestine and the State of Israel, understood their collective political situation and what they ought to do about it, the nature of Diaspora and the claims of Zionism, and the political and moral wages of powerlessness. American readers might compare “In the City of Slaughter” to Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn or indeed Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin in the sense that their searing moral and political claims about burning political problems had an immediate and lasting impact. “In the City of Slaughter” is Haim Nahman Bialik’s poem about the 1903 Kishinev pogrom, a terrible ethnic riot during which the large Jewish community of this small city in the Russian Empire was attacked over the course of three days by crowds of their Gentile neighbors. Although popular images of the life of Russia’s Jews, who numbered nearly six million at the turn of the twentieth century, sometimes treat such anti-Jewish violence as routine, in fact there had been nothing like the Kishinev pogrom before it happened.