The Kiwi, 1966

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Survey of Recent New Zealand Writing TREVOR REEVES

A Survey of Recent New Zealand Writing TREVOR REEVES O achieve any depth or spread in an article attempt• ing to cover the whole gamut of New Zealand writing * must be deemed to be a New Zealand madman's dream, but I wonder if it would be so difficult for people overseas, particularly in other parts of the Commonwealth. It would appear to them, perhaps, that two or three rather good poets have emerged from these islands. So good, in fact, that their appearance in any anthology of Common• wealth poetry would make for a matter of rather pleasurable comment and would certainly not lower the general stand• ard of the book. I'll come back to these two or three poets presently, but let us first consider the question of New Zealand's prose writers. Ah yes, we have, or had, Kath• erine Mansfield, who died exactly fifty years ago. Her work is legendary — her Collected Stories (Constable) goes from reprint to reprint, and indeed, pirate printings are being shovelled off to the priting mills now that her fifty year copyright protection has run out. But Katherine Mansfield never was a "New Zealand writer" as such. She left early in the piece. But how did later writers fare, internationally speaking? It was Janet Frame who first wrote the long awaited "New Zealand Novel." Owls Do Cry was published in 1957. A rather cruel but incisive novel, about herself (everyone has one good novel in them), it centred on her own childhood experiences in Oamaru, a small town eighty miles north of Dunedin -— a town in which rough farmers drove sheep-shit-smelling American V-8 jalopies inexpertly down the main drag — where the local "bikies" as they are now called, grouped in vociferous RECENT NEW ZEALAND WRITING 17 bunches outside the corner milk bar. -

Newsletter – 15 April 2010 ISSN: 1178-9441

INTERNATIONAL INSTITUTE OF MODERN LETTERS Te P¯utahi Tuhi Auaha o te Ao Newsletter – 15 April 2010 ISSN: 1178-9441 This is the 154th in a series of occasional newsletters from the Victoria University centre of the International Institute of Modern Letters. For more information about any of the items, please email [email protected]. 1. Second trimester writing courses at the IIML ................................................... 2 2. Our first PhD ........................................................................................................ 2 3. Legend of a suicide author to appear in Wellington .......................................... 2 4. The Godfather comes to town .............................................................................. 3 5. From the whiteboard ............................................................................................ 3 6. Glyn Maxwell’s masterclass ................................................................................ 3 7. This and That ........................................................................................................ 3 8. Racing colours ....................................................................................................... 4 9. New Zealand poetry goes Deutsch ...................................................................... 4 10. Phantom poetry ................................................................................................. 5 11. Making something happen .............................................................................. -

Allegory in the Fiction of Janet Frame

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. ALLEGORY IN THE FICTION OF JANET FRAME A thesis in partial fulfIlment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English at Massey University. Judith Dell Panny 1991. i ABSTRACT This investigation considers some aspects of Janet Frame's fiction that have hitherto remained obscure. The study includes the eleven novels and the extended story "Snowman, Snowman". Answers to questions raised by the texts have been found within the works themselves by examining the significance of reiterated and contrasting motifs, and by exploring the most literal as well as the figurative meanings of the language. The study will disclose the deliberate patterning of Frame's work. It will be found that nine of the innovative and cryptic fictions are allegories. They belong within a genre that has emerged with fresh vigour in the second half of this century. All twelve works include allegorical features. Allegory provides access to much of Frame's irony, to hidden pathos and humour, and to some of the most significant questions raised by her work. By exposing the inhumanity of our age, Frame prompts questioning and reassessment of the goals and values of a materialist culture. Like all writers of allegory, she focuses upon the magic of language as the bearer of truth as well as the vehicle of deception. -

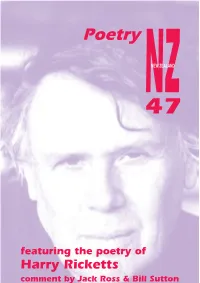

PNZ 47 Digital Version

Poetry NZNEW ZEALAND 47 featuring the poetry of 1 Harry Ricketts comment by Jack Ross & Bill Sutton Poetry NZ Number 47, 2013 Two issues per year Editor: Alistair Paterson ONZM Submissions: Submit at any time with a stamped, self-addressed envelope (and an email address if available) to: Poetry NZ, 34B Methuen Road, Avondale, Auckland 0600, New Zealand or 1040 E. Paseo El Mirador, Palm Springs, CA 92262-4837, USA Please note that overseas submissions cannot be returned, and should include an email address for reply. Postal subscriptions: Poetry NZ, 37 Margot Street, Epsom, Auckland 1051, New Zealand or 1040 E. Paseo el Mirador, Palm Springs, CA 92262-4837, USA Postal subscription Rates: US Subscribers (by air) One year (2 issues) $30.00 $US24.00 Two years (4 issues) $55.00 $US45.00 Libraries: 1 year $32.00 $US25.00 Libraries: 2 years $60.00 $US46.00 Other countries One year (2 issues) $NZ36.00 Two years (4 issues) $NZ67.00 Online subscriptions: To take out a subscription go to www.poetrynz.net and click on ‘subscribe’. The online rates are listed on this site. When your subscription application is received it will be confi rmed by email, and your fi rst copy of the magazine will then be promptly posted out to you. 2 Poetry NZ 47 Alistair Paterson Editor Puriri Press & Brick Row Auckland, New Zealand Palm Springs, California, USA September 2013 3 ISSN 0114-5770 Copyright © 2013 Poetry NZ 37 Margot Street, Epsom, Auckland 1051, New Zealand All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo copying, recording or otherwise without the written permission of the publisher. -

Clough and His Poetry, James Bertram 141

&& A New Zealand Qyarter!Jr VOLUME SEVENTEEN Reprinted with the permission of The Caxton Press JOHNSON REPRINT CORPORATION JOHNSON REPRINT COMPANY LTD. 111 Fifth Avenue, New York, N. Y. 10003 Berkeley Square House, London, W. 1 LANDFALL is published with the aid of a grant from the New Zealand Literary Fund. First reprinting, 196S, Johnson Reprint Corporation Printed in the United States of America A New Zealand Quarterly edited by Charles Brasch and published by The Caxton Press CON'I'EN'I'S 107 Against T e Rauparaha, Alistair Camp bell 108 Outback, Kenneth McKenney 111 Watching you drift in shallow sleep, Alan Roddick 112 A Descendant of the Mountain, Albert W endt 113 To One Born on the Day of my Death, Charles Doyle 118 Three Poems, Raymond Ward 119 Towards a Zealand Drama, Erle Nelson 122 Reconstructions, Kevin Lawson 134 Five Poems, Peter Bland 137 Clough and his Poetry, James Bertram 141 COMMENTARIES: Canadian Letter, George W halley 155 Using Zealand House, f. M. Thomson 162 The Opera Season, John Steele 165 Joseph Banks: the Endeavour Journal, Colin Beer 168 Richmonds and Atkinsons, W. H. Oliver 177 REVIEWS:, Zealand Poetry Yearbook, Owen Leeming 187 The Edge of the Alphabet, Thomas Crawford 192 The Last Pioneer, R. A. Copland 195 Auckland Gallery Lectures, Wystan Curnow 196 Inheritors of a Dream, W. f. Gardner 199 Correspondence, Stella Jones, L. Cleveland, R. A. Copland, Don Holdaway, f. L. Ewing, R. H. Lockstone, R. McD. Chapman 201 Paintings by Don Binney, Bryan Dew, Garth Tapper, Dennis Turner VOLUME SEVENTEEN NUMBER TWO JUNE 1963 Notes LANDFALL has neither printed nor sought stories and poems by writers in other countries; not out of insularity, but on the ground that its limited space ought to be kept for the work of New Zealand writers, who had, and have, few means of publishing at home. -

Denis Glover

LA:J\(JJFA LL ' Zealam 'terly 'Y' and v.,,,.,,,,,,.,.,,," by 1 'On ,,'re CON'I'EN'TS Notes 3 City and Suburban, Frank Sargeson 4 Poems of the Mid-Sixties, K. 0. Arvidson, Peter Bland, Basil Dowling, Denis Glover, Paul Henderson, Kevin Ireland, Louis Johnson, Owen Leeming, Raymond Ward, Hubert Witheford, Mark Young 10 Artist, Michael Gifkins 33 Poems from the Panjabi, Amrita Pritam 36 Beginnings, Janet Frame 40 A Reading of Denis Glover, Alan Roddick 48 COMMENTARIES; Indian Letter, Mahendra Kulasrestha 58 Greer Twiss, Paul Beadle 63 After the Wedding, Kirsty Northcote-Bade 65 REVIEWS: A Walk on the Beach, Dennis McEldowney 67 The Cunninghams, Children of the Poor, K. 0. Arvidson 69 Bread and a Pension, MacD. P. Jackson 74 Wild Honey, J. E. P. T homson 83 Ambulando, R. L. P. Jackson 86 Byron the Poet, !an Jack 89 Studies of a Small Democracy, W. J. Gardner 91 Correspondence, W. K. Mcllroy, Lawrence Jones, Atihana Johns 95 Sculpture by Greer T wiss Cover design by V ere Dudgeon VOLUME NINETEEN NUMBER ONE MARCH 1965 LANDFALL is published with the aid of a grant from the New Zealand Literary Fund. LANDFALL is printed and published by The Caxton Press at 119 Victoria Street, Christchurch. The annual subscription is 20s. net post free, and should be sent to the above address. All contributions used will be paid for. Manuscripts should be sent to the editor at the above address; they cannot be returned unless accompanied by a stamped and addressed envelope. Notes PoETs themselves pass judgment on what they say by their way of saying it. -

![U DSG Papers of Howard Sergeant, Including [1930]-1995 the Archives of 'Outposts' Poetry Magazine](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4831/u-dsg-papers-of-howard-sergeant-including-1930-1995-the-archives-of-outposts-poetry-magazine-2844831.webp)

U DSG Papers of Howard Sergeant, Including [1930]-1995 the Archives of 'Outposts' Poetry Magazine

Hull History Centre: Howard Sergeant, inc 'Outposts' poetry magazine U DSG Papers of Howard Sergeant, including [1930]-1995 the Archives of 'Outposts' poetry magazine Biographical Background: Herbert ('Howard') Sergeant was born in Hull in 1914 and qualified as an accountant. He served in the RAF and the Air Ministry during the Second World War and with the assistance of his friend Lionel Monteith, edited and published the first issue of his poetry magazine 'Outposts' in February 1944. Outposts is the longest running independent poetry magazine in Britain. Sergeant had been writing poetry since childhood and his first poem to be published was 'Thistledown magic', in 'Chambers Journal' in 1943. 'Outposts' was conceived in wartime and its early focus was on poets 'who, by reason of the particular outposts they occupy, are able to visualise the dangers which confront the individual and the whole of humanity, now and after the war' (editorial, 'Outposts', no.1). Over the decades, the magazine specialised in publishing unrecognised poets alongside the well established. Sergeant deliberately avoided favouring any particular school of poetry, and edited 'Mavericks: an anthology', with Dannie Abse, in 1957, in support of this stance. Sergeant's own poetry was included in the first issue of 'Outposts' (but rarely thereafter) and his first published collection, 'The Leavening Air', appeared in 1946. He was involved in setting up the Dulwich Group (a branch of the British Poetry Association) in 1949, and again, when it re-formed in 1960. In 1956, Sergeant published the first of the Outposts Modern Poets Series of booklets and hardbacks devoted to individual poets. -

Geographies of Displacement

Commonwealth Essays and Studies 38.2 | 2016 Geographies of Displacement Claire Omhovère (dir.) Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/ces/4833 DOI: 10.4000/ces.4833 ISSN: 2534-6695 Publisher SEPC (Société d’études des pays du Commonwealth) Printed version Date of publication: 1 April 2016 ISSN: 2270-0633 Electronic reference Claire Omhovère (dir.), Commonwealth Essays and Studies, 38.2 | 2016, “Geographies of Displacement” [Online], Online since 06 April 2021, connection on 01 July 2021. URL: https://journals.openedition.org/ ces/4833; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/ces.4833 Commonwealth Essays and Studies is licensed under a Licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. Geographies of Displacement Vol. 38, N°2, Spring 2016 Geographies of Displacement Claire OMHOVÈRE • Introduction......................................................................................................................................................................5 Elizabeth RECHNIEWSKI • Geographies of Displacement in a Colonial Context: Allen F. Gardiner’s Writings on Australia ...................... 9 Catherine DELMAS • Transplanting Seeds in Diasporic Literature: Michael Ondaatje’s The Cat’s Table and Amitav Ghosh’s Sea of Poppies and River of Smoke .............................................................................................19 Giuseppe SOFO • The Poetics of Displacement in Indian English Fiction: Kipling’s The Man Who Would Be King, Rushdie’s East, West and -

Pākehā Constructions of National Identity in New Zealand Literary Anthologies

CREATING NEW ZEALAND: PĀKEHĀ CONSTRUCTIONS OF NATIONAL IDENTITY IN NEW ZEALAND LITERARY ANTHOLOGIES A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Victoria University of Wellington by SUSAN WILD Victoria University of Wellington 2015 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my grateful thanks for the support and assistance of my two supervisors at Victoria University, Professors Mark Williams and Peter Whiteford, who have provided invaluable guidance in bringing the thesis to its completion; Professor Vincent O’Sullivan and Dr. Brian Opie provided early assistance; I am appreciative also for the helpful advice and encouragement given by Ed Mares, and for the support and patience of my family. This was especially helpful during the disruptive period of the Christchurch earthquakes, and in their long aftermath. I wish also to state my appreciation for the services of the staff at the National Library of New Zealand, the Alexander Turnbull Library, the MacMillan Brown Library, the Mitchell Library, Sydney, and the libraries of Victoria University of Wellington and the University of Canterbury – the extensive collections of New Zealand literature held at these institutions and others comprise an enduring taonga. 1 ABSTRACT The desire to construct a sense of home and the need to belong are basic to human society, and to the processes of its cultural production. Since the beginning of New Zealand’s European colonial settlement, the determination to create and reflect a separate and distinctive collective identity for the country’s Pākehā population has been the primary focus of much local creative and critical literature. -

Commonwealth Essays and Studies, 38.2 | 2016 Valérie Baisnée, “Through the Long Corridor of Distance”: Space and Self in C

Commonwealth Essays and Studies 38.2 | 2016 Geographies of Displacement Valérie Baisnée, “Through the long corridor of distance”: Space and Self in Contemporary New Zealand Women’s Autobiographies Patricia Neville Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/ces/5629 DOI: 10.4000/ces.5629 ISSN: 2534-6695 Publisher SEPC (Société d’études des pays du Commonwealth) Printed version Date of publication: 1 April 2016 Number of pages: 133-134 ISSN: 2270-0633 Electronic reference Patricia Neville, “Valérie Baisnée, “Through the long corridor of distance”: Space and Self in Contemporary New Zealand Women’s Autobiographies”, Commonwealth Essays and Studies [Online], 38.2 | 2016, Online since 06 April 2021, connection on 01 July 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/ces/5629 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/ces.5629 This text was automatically generated on 1 July 2021. Commonwealth Essays and Studies is licensed under a Licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. Valérie Baisnée, “Through the long corridor of distance”: Space and Self in C... 1 Valérie Baisnée, “Through the long corridor of distance”: Space and Self in Contemporary New Zealand Women’s Autobiographies Patricia Neville REFERENCES Valérie Baisnée. “Through the long corridor of distance”: Space and Self in Contemporary New Zealand Women’s Autobiographies. Amsterdam & New York: Rodopi, Cross/Cultures 175, 2014. 156 p. ISBN: 978-9-04203-868-4. €42.00, $54.00 “Writing about one’s past involves both invention and exorcisms: finding what was lost and would have been permanently lost otherwise; and freeing oneself of the burden of it, when it is a burden.” Charles Brasch, Journals, 1968. -

Spring 2014, Volume 5, Issue 3

. Poetry Notes Spring 2014 Volume 5, Issue 3 ISSN 1179-7681 Quarterly Newsletter of PANZA Zealand. She was included in a Inside this Issue Welcome bibliography of legends/myths for her collection Māori Love Legends Hello and welcome to issue 19 of published after the First World War in Welcome Poetry Notes, the newsletter of PANZA, 1920. 1 the newly formed Poetry Archive of As with some other poets profiled Mark Pirie on Marieda New Zealand Aotearoa. recently in Poetry Notes, Batten does Batten (1875-1933) Poetry Notes will be published quarterly not appear in any New Zealand and will include information about anthology that I’m aware of, but she is Classic New Zealand goings on at the Archive, articles on listed with other New Zealand poets of poetry by Noeline historical New Zealand poets of interest, this period in New Zealand Literature 6 Gannaway occasional poems by invited poets and a Authors’ Week 1936: Annals of New record of recently received donations to Zealand Literature: being a List of New Comment on Travis the Archive. Zealand Authors and their works with Wilson (1924-1983) 7 Articles and poems are copyright in the introductory essays and verses, page 40: names of the individual authors. National Poetry Day poem: “Batten, Ida Marieda (Mrs Cook [sic]). The newsletter will be available for free 1915, Star dust and sea foam (v); 9 Jean Batten download from the Poetry Archive’s c1918, Love-life (v); 1920, Maori love website: legends (v); 1925, Silver nights (v).” Tribute to Warren Dibble Marieda Batten appears with the New 10 http://poetryarchivenz.wordpress.com Zealand poets Jessie Mackay, Alan E. -

Issue 32 April 2019

ISSN 2040- 2597 Issue 32 April 2019 Published by the Katherine Mansfield Society, Bath, Photo: Maxime Luce: Notre Dame de Paris 1900 Issue 32 April 2019 2 Contents KMS News and Prizes p. 3 ‘Arthur Ransome and Katherine Mansfield: Lives Lived in Parallel, 1908-1913’ by Cheryl Paget p.4 ‘Arthur Ransome and Katherine Mansfield - Parallel Lives’ by Dayll McCahon p. 11 Conference Announcement: Inspirations and Influences, Krakow, Poland July 2019 p. 13 Review: Katherine Mansfield and Periodical Culture by Gerri Kimber p. 14 Announcement: Katherine Mansfield Society Annual Birthday Lecture 2019 p. 17 ‘Her Bright Image’ – Some Omissions by Moira Taylor p.18 Interview: The music of Gurdjieff transcribed for guitar [with Gunter Herbig] p. 22 ‘My Corona’ by Denise Roughan p.27 Praise for ‘Worldly Goods’ “Alice Petersen’s stories present small worlds containinG biG emotional ranGe. Whether at a luthier’s workshop or sellinG china or teachinG Latin, Petersen’s people work towards truer selves. She presents their efforts in a style that is always clear – clear as a well-played cello.” – Cynthia Flood Alice Petersen’s Worldly Goods is our prize this issue: details below Issue 32 April 2019 3 It is with sadness that we reflect on the fire at Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris: this reminded me that KM loved this place and wrote in her journal, May 1915: I am sitting on a broad bench in the sun hard by Notre Dame. In front of me there is a hedge of ivy. An old man walked along with a basket on his arm picking off the withered leaves.