Writers in New Zealand: a Questionnaire 36 Commentaries : NUCLEAR DISARMAMENT-ANOTHER VIEW, A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Survey of Recent New Zealand Writing TREVOR REEVES

A Survey of Recent New Zealand Writing TREVOR REEVES O achieve any depth or spread in an article attempt• ing to cover the whole gamut of New Zealand writing * must be deemed to be a New Zealand madman's dream, but I wonder if it would be so difficult for people overseas, particularly in other parts of the Commonwealth. It would appear to them, perhaps, that two or three rather good poets have emerged from these islands. So good, in fact, that their appearance in any anthology of Common• wealth poetry would make for a matter of rather pleasurable comment and would certainly not lower the general stand• ard of the book. I'll come back to these two or three poets presently, but let us first consider the question of New Zealand's prose writers. Ah yes, we have, or had, Kath• erine Mansfield, who died exactly fifty years ago. Her work is legendary — her Collected Stories (Constable) goes from reprint to reprint, and indeed, pirate printings are being shovelled off to the priting mills now that her fifty year copyright protection has run out. But Katherine Mansfield never was a "New Zealand writer" as such. She left early in the piece. But how did later writers fare, internationally speaking? It was Janet Frame who first wrote the long awaited "New Zealand Novel." Owls Do Cry was published in 1957. A rather cruel but incisive novel, about herself (everyone has one good novel in them), it centred on her own childhood experiences in Oamaru, a small town eighty miles north of Dunedin -— a town in which rough farmers drove sheep-shit-smelling American V-8 jalopies inexpertly down the main drag — where the local "bikies" as they are now called, grouped in vociferous RECENT NEW ZEALAND WRITING 17 bunches outside the corner milk bar. -

Newsletter – 15 April 2010 ISSN: 1178-9441

INTERNATIONAL INSTITUTE OF MODERN LETTERS Te P¯utahi Tuhi Auaha o te Ao Newsletter – 15 April 2010 ISSN: 1178-9441 This is the 154th in a series of occasional newsletters from the Victoria University centre of the International Institute of Modern Letters. For more information about any of the items, please email [email protected]. 1. Second trimester writing courses at the IIML ................................................... 2 2. Our first PhD ........................................................................................................ 2 3. Legend of a suicide author to appear in Wellington .......................................... 2 4. The Godfather comes to town .............................................................................. 3 5. From the whiteboard ............................................................................................ 3 6. Glyn Maxwell’s masterclass ................................................................................ 3 7. This and That ........................................................................................................ 3 8. Racing colours ....................................................................................................... 4 9. New Zealand poetry goes Deutsch ...................................................................... 4 10. Phantom poetry ................................................................................................. 5 11. Making something happen .............................................................................. -

RARE BOOK AUCTION Wednesday 24Th August 2011 11

RARE BOOK AUCTION Wednesday 24th August 2011 11 68 77 2 293 292 267 54 276 25 Rare Books, Maps, Ephemera and Early Photographs AUCTION: Wednesday 24th August, 2011, at 12 noon, 3 Abbey Street, Newton, Auckland VIEWING TIMES CONTACT Sunday 21st August 11.00am - 3.00 pm All inquiries to: Monday 22nd August 9.00am - 5.00pm Pam Plumbly - Rare book Tuesday 23rd August 9.00am - 5.00pm consultant at Art+Object Wednesday 24th August - viewing morning of sale. Phones - Office 09 378 1153, Mobile 021 448200 BUYER’S PREMIUM Art + Object 09 354 4646 Buyers shall pay to Pam Plumbly @ART+OBJECT 3 Abbey St, Newton, a premium of 17% of the hammer price plus GST Auckland. of 15% on the premium only. www.artandobject.co.nz Front cover features an illustration from Lot 346, Beardsley Aubrey, James Henry et al; The Yellow Book The Pycroft Collection of Rare New Zealand, Australian and Pacific Books 3rd & 4th November 2011 ART+OBJECT is pleased to announce the sale of the last great New Zealand library still remaining in private hands. Arthur Thomas Pycroft (1875 – 1971) a dedicated naturalist, scholar, historian and conservationist assembled the collection over seven decades. Arthur Pycroft corresponded with Sir Walter Buller. He was extremely well informed and on friendly terms with all the leading naturalists and museum directors of his era. This is reflected in the sheer scope of his collecting and an acutely sensitive approach to acquisitions. The library is rich in rare books and pamphlets, associated with personalities who shaped early New Zealand history. -

Allegory in the Fiction of Janet Frame

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. ALLEGORY IN THE FICTION OF JANET FRAME A thesis in partial fulfIlment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English at Massey University. Judith Dell Panny 1991. i ABSTRACT This investigation considers some aspects of Janet Frame's fiction that have hitherto remained obscure. The study includes the eleven novels and the extended story "Snowman, Snowman". Answers to questions raised by the texts have been found within the works themselves by examining the significance of reiterated and contrasting motifs, and by exploring the most literal as well as the figurative meanings of the language. The study will disclose the deliberate patterning of Frame's work. It will be found that nine of the innovative and cryptic fictions are allegories. They belong within a genre that has emerged with fresh vigour in the second half of this century. All twelve works include allegorical features. Allegory provides access to much of Frame's irony, to hidden pathos and humour, and to some of the most significant questions raised by her work. By exposing the inhumanity of our age, Frame prompts questioning and reassessment of the goals and values of a materialist culture. Like all writers of allegory, she focuses upon the magic of language as the bearer of truth as well as the vehicle of deception. -

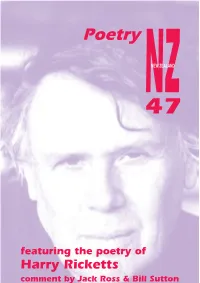

PNZ 47 Digital Version

Poetry NZNEW ZEALAND 47 featuring the poetry of 1 Harry Ricketts comment by Jack Ross & Bill Sutton Poetry NZ Number 47, 2013 Two issues per year Editor: Alistair Paterson ONZM Submissions: Submit at any time with a stamped, self-addressed envelope (and an email address if available) to: Poetry NZ, 34B Methuen Road, Avondale, Auckland 0600, New Zealand or 1040 E. Paseo El Mirador, Palm Springs, CA 92262-4837, USA Please note that overseas submissions cannot be returned, and should include an email address for reply. Postal subscriptions: Poetry NZ, 37 Margot Street, Epsom, Auckland 1051, New Zealand or 1040 E. Paseo el Mirador, Palm Springs, CA 92262-4837, USA Postal subscription Rates: US Subscribers (by air) One year (2 issues) $30.00 $US24.00 Two years (4 issues) $55.00 $US45.00 Libraries: 1 year $32.00 $US25.00 Libraries: 2 years $60.00 $US46.00 Other countries One year (2 issues) $NZ36.00 Two years (4 issues) $NZ67.00 Online subscriptions: To take out a subscription go to www.poetrynz.net and click on ‘subscribe’. The online rates are listed on this site. When your subscription application is received it will be confi rmed by email, and your fi rst copy of the magazine will then be promptly posted out to you. 2 Poetry NZ 47 Alistair Paterson Editor Puriri Press & Brick Row Auckland, New Zealand Palm Springs, California, USA September 2013 3 ISSN 0114-5770 Copyright © 2013 Poetry NZ 37 Margot Street, Epsom, Auckland 1051, New Zealand All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo copying, recording or otherwise without the written permission of the publisher. -

Clough and His Poetry, James Bertram 141

&& A New Zealand Qyarter!Jr VOLUME SEVENTEEN Reprinted with the permission of The Caxton Press JOHNSON REPRINT CORPORATION JOHNSON REPRINT COMPANY LTD. 111 Fifth Avenue, New York, N. Y. 10003 Berkeley Square House, London, W. 1 LANDFALL is published with the aid of a grant from the New Zealand Literary Fund. First reprinting, 196S, Johnson Reprint Corporation Printed in the United States of America A New Zealand Quarterly edited by Charles Brasch and published by The Caxton Press CON'I'EN'I'S 107 Against T e Rauparaha, Alistair Camp bell 108 Outback, Kenneth McKenney 111 Watching you drift in shallow sleep, Alan Roddick 112 A Descendant of the Mountain, Albert W endt 113 To One Born on the Day of my Death, Charles Doyle 118 Three Poems, Raymond Ward 119 Towards a Zealand Drama, Erle Nelson 122 Reconstructions, Kevin Lawson 134 Five Poems, Peter Bland 137 Clough and his Poetry, James Bertram 141 COMMENTARIES: Canadian Letter, George W halley 155 Using Zealand House, f. M. Thomson 162 The Opera Season, John Steele 165 Joseph Banks: the Endeavour Journal, Colin Beer 168 Richmonds and Atkinsons, W. H. Oliver 177 REVIEWS:, Zealand Poetry Yearbook, Owen Leeming 187 The Edge of the Alphabet, Thomas Crawford 192 The Last Pioneer, R. A. Copland 195 Auckland Gallery Lectures, Wystan Curnow 196 Inheritors of a Dream, W. f. Gardner 199 Correspondence, Stella Jones, L. Cleveland, R. A. Copland, Don Holdaway, f. L. Ewing, R. H. Lockstone, R. McD. Chapman 201 Paintings by Don Binney, Bryan Dew, Garth Tapper, Dennis Turner VOLUME SEVENTEEN NUMBER TWO JUNE 1963 Notes LANDFALL has neither printed nor sought stories and poems by writers in other countries; not out of insularity, but on the ground that its limited space ought to be kept for the work of New Zealand writers, who had, and have, few means of publishing at home. -

The Sinking of the Rainbow Warrior: Responses to an International Act of Terrorism

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by NECTAR Journal of Postcolonial Cultures and Societies ISSN No. 1948-1845 (Print); 1948-1853 (Electronic) The sinking of the rainbow warrior: Responses to an international act of terrorism Janet Wilson Introduction: the Rainbow Warrior Affair The Rainbow Warrior affair, an act of sabotage against the flagship of the Greenpeace fleet, the Rainbow Warrior, when berthed at Marsden wharf in Auckland harbour on 10th July 1985, dramatised in unprecedented ways issues of neo-imperialism, national security, eco-politics and postcolonialism in New Zealand. The bombing of the yacht by French secret service agents effectively prevented its participation in a Nuclear Free Pacific campaign in which it was to have headed the Pacific Fleet Flotilla to Moruroa atoll protesting French nuclear testing. Outrage was compounded by tragedy: the vessel’s Portuguese photographer, Fernando Pereira, went back on board to get his camera after the first detonation and was drowned in his cabin following the second one. The evidence of French Secret Service (Direction Generale de la Securite Exterieure or DGSE) involvement which sensationally emerged in the following months, not only enhanced New Zealand’s status as a small nation and wrongful victim of French neo-colonial ambitions, it dramatically magnified Greenpeace’s role as coordinator of New Zealand and Pacific resistance to French bomb-testing. The stand-off in New Zealand –French political relations for almost a decade until French bomb testing in the Pacific ceased in 1995 notwithstanding, this act of terrorism when reviewed after almost 25 years in the context of New Zealand’s strategic and political negotiations of the 1980s, offers a focus for considering the changing composition of national and regional postcolonial alliances during Cold War politics. -

August 2010 PROTECTION of AUTHOR

THE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY PROTECTION OF AUTHOR ’S COPYRIGHT This copy has been supplied by the Library of the University of Otago on the understanding that the following conditions will be observed: 1. To comply with s56 of the Copyright Act 1994 [NZ], this thesis copy must only be used for the purposes of research or private study. 2. The author's permission must be obtained before any material in the thesis is reproduced, unless such reproduction falls within the fair dealing guidelines of the Copyright Act 1994. Due acknowledgement must be made to the author in any citation. 3. No further copies may be made without the permission of the Librarian of the University of Otago. August 2010 UNIVERSITY OF OTAGO LIBRARY Declaration concerning thesis Author's name: Cv'C:l 0\1 Title of thesis: Tk \Pvo ·ks A- V'Vl.tYv~ ~ f- ~ Vi ~" ~ "Y"\ c.r Degree: 1D AC .J _ 1 Q Gt cVI'- <f- h__z c-+ ... w (> . ncV'~- J (j l 0!b)- ltt?-1 Department: H- (S +o ·'"'"'(}- I agree that this thesis may be consulted for research and study purposes and that reasonable quotation may be made from it, provided that proper acknowledgement of its use is made. I expect that my permission will be obtained before any material is published. I consent to this thesis being copied in part or in whole for i) a library ii) an individual at the discretion of the Librarian of the University of Otago. Or ]; • 'ii':i:se :t=e msaa:;g:r :tl:!e aae:~,tQ se~~lit.;i,e~s ... -

Denis Glover

LA:J\(JJFA LL ' Zealam 'terly 'Y' and v.,,,.,,,,,,.,.,,," by 1 'On ,,'re CON'I'EN'TS Notes 3 City and Suburban, Frank Sargeson 4 Poems of the Mid-Sixties, K. 0. Arvidson, Peter Bland, Basil Dowling, Denis Glover, Paul Henderson, Kevin Ireland, Louis Johnson, Owen Leeming, Raymond Ward, Hubert Witheford, Mark Young 10 Artist, Michael Gifkins 33 Poems from the Panjabi, Amrita Pritam 36 Beginnings, Janet Frame 40 A Reading of Denis Glover, Alan Roddick 48 COMMENTARIES; Indian Letter, Mahendra Kulasrestha 58 Greer Twiss, Paul Beadle 63 After the Wedding, Kirsty Northcote-Bade 65 REVIEWS: A Walk on the Beach, Dennis McEldowney 67 The Cunninghams, Children of the Poor, K. 0. Arvidson 69 Bread and a Pension, MacD. P. Jackson 74 Wild Honey, J. E. P. T homson 83 Ambulando, R. L. P. Jackson 86 Byron the Poet, !an Jack 89 Studies of a Small Democracy, W. J. Gardner 91 Correspondence, W. K. Mcllroy, Lawrence Jones, Atihana Johns 95 Sculpture by Greer T wiss Cover design by V ere Dudgeon VOLUME NINETEEN NUMBER ONE MARCH 1965 LANDFALL is published with the aid of a grant from the New Zealand Literary Fund. LANDFALL is printed and published by The Caxton Press at 119 Victoria Street, Christchurch. The annual subscription is 20s. net post free, and should be sent to the above address. All contributions used will be paid for. Manuscripts should be sent to the editor at the above address; they cannot be returned unless accompanied by a stamped and addressed envelope. Notes PoETs themselves pass judgment on what they say by their way of saying it. -

Canadian Poetry and the Regional Anthology, R

A New•••aa Zealand Qgarter!J' VOLUME SIXTEEN 1962 Reprinted with the permission of The Caxton Press JOHNSON REPRINT CORPORATION JOHNSON REPRINT COMPANY LTD. 111 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10003 Berkeley Square House, London, W. 1 LANDFALL is published with the aid of a grant from the New Zealand Literary Fund. Corrigendum. Landfall 61, March 1962, p. 57, line 5, should read: day you will understand why', or even, 'Learn this now, because I First reprinting, 1968, Johnson Reprint Corporation Printed in the United States of America Landfall A New Zealand Quarterly edited by Charles Brasch and published by The Caxton Press CONTENTS Notes 107 The Brothers, Kevin Lawson 108 Snowfall, Ruth Dallas 109 The Greaser's Story, 0. E. Middleton IIO Three Poems, Raymond Ward 129 Canadian Poetry and the Regional Anthology, R. T. Robertson 134 Washed up on Island Bay, W. H. Oliver 147 New Zealand Since the War (7), Bill Pearson 148 COMMENTARIES : Canadian Letter, Roy Daniells 180 The Broadcasting Corporation Act, R. ]. Harrison 185 REVIEWS: The Turning Wheel, ]ames Bertram 188 Poetry of the Maori, Alan Roddick 192 New Novels, Paul Day 195 Correspondence, David Hall, W. ]. Scott, R. T. Robertson, Wystan Curnow Paintings by Pam Cotton VOLUME SIXTEEN NUMBER TWO JUNE 1962 Notes ON I APRIL, the New Zealand Broadcasting Service became a Cor- poration, and ceased to be a government department. That was the first change necessary if broadcasting, with TV, is to play its proper role in New Zealand life. On another page, Mr Harrison examines the Broadcasting Corporation Act and the measure of independence which it gives the Corporation. -

![U DSG Papers of Howard Sergeant, Including [1930]-1995 the Archives of 'Outposts' Poetry Magazine](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4831/u-dsg-papers-of-howard-sergeant-including-1930-1995-the-archives-of-outposts-poetry-magazine-2844831.webp)

U DSG Papers of Howard Sergeant, Including [1930]-1995 the Archives of 'Outposts' Poetry Magazine

Hull History Centre: Howard Sergeant, inc 'Outposts' poetry magazine U DSG Papers of Howard Sergeant, including [1930]-1995 the Archives of 'Outposts' poetry magazine Biographical Background: Herbert ('Howard') Sergeant was born in Hull in 1914 and qualified as an accountant. He served in the RAF and the Air Ministry during the Second World War and with the assistance of his friend Lionel Monteith, edited and published the first issue of his poetry magazine 'Outposts' in February 1944. Outposts is the longest running independent poetry magazine in Britain. Sergeant had been writing poetry since childhood and his first poem to be published was 'Thistledown magic', in 'Chambers Journal' in 1943. 'Outposts' was conceived in wartime and its early focus was on poets 'who, by reason of the particular outposts they occupy, are able to visualise the dangers which confront the individual and the whole of humanity, now and after the war' (editorial, 'Outposts', no.1). Over the decades, the magazine specialised in publishing unrecognised poets alongside the well established. Sergeant deliberately avoided favouring any particular school of poetry, and edited 'Mavericks: an anthology', with Dannie Abse, in 1957, in support of this stance. Sergeant's own poetry was included in the first issue of 'Outposts' (but rarely thereafter) and his first published collection, 'The Leavening Air', appeared in 1946. He was involved in setting up the Dulwich Group (a branch of the British Poetry Association) in 1949, and again, when it re-formed in 1960. In 1956, Sergeant published the first of the Outposts Modern Poets Series of booklets and hardbacks devoted to individual poets. -

Pam Plumbly @ Art+Object Rare Book Auction

PAM PLUMBLY @ ART+OBJECT RARE BOOK AUCTION WEDNESDAY 20th APRIL 2011 17 45 ART+OBJECT Rare Books, Maps, Ephemera and Early Photographs Features and important collection of New Zealand literature; First Edtion of George French Angas’s “The New Zealanders Illustrated” , Thomas McLean 1847; W.W. 1. Gallipoli Diary; Photographs by W.H.T. Pardington; Set of lantern slides of Antarctic scenes by Herbert Ponting; A large collection of postcards. AUCTION Wednesday 20th April, 2011, at 12 noon. 3 Abbey Street Newton Auckland 1145 VIEWING TIMES Sunday 17th April 11.00am - 3.00 pm Monday 18th April 9.00am - 5.00pm Tuesday 19th April 9.00am - 5.00pm Wednesday 20th April - viewing morning of sale. BUYER’S PREMIUM Buyers shall pay to Pam Plumbly @ART+OBJECT a premium of 15% of the hammer price plus GST of 15% on the premium only. contact All inquiries to: Pam Plumbly - Rare book consultant at Art+Object Phones - Office 09 378 1153, Mobile 021 448200 Art + Object 09 354 4646 3 Abbey St, Newton, Auckland. [email protected] www.artandobject.co.nz www.trevorplumbly.co.nz Consignments are now invited for the next rare book auction to be held at ART+OBJECT in August 2011 Front cover; ANGAS, GEORGE FRENCH, The New Zealanders [ in 2 Volumes ] Back cover; BRIMER, SERJEANT CYRIL THORNTON, Gallipoli Diary ABSENTEE BID FORM auction WEDNESDAY 20TH APRIL 2011 PAM PLUMBLy@ART&OBJEct This completed and signed form authorizes PAM PLUMBLY@ART+OBJECT to bid at the above mentioned auction or the following lots up to the prices indicated below.