Clough and His Poetry, James Bertram 141

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Survey of Recent New Zealand Writing TREVOR REEVES

A Survey of Recent New Zealand Writing TREVOR REEVES O achieve any depth or spread in an article attempt• ing to cover the whole gamut of New Zealand writing * must be deemed to be a New Zealand madman's dream, but I wonder if it would be so difficult for people overseas, particularly in other parts of the Commonwealth. It would appear to them, perhaps, that two or three rather good poets have emerged from these islands. So good, in fact, that their appearance in any anthology of Common• wealth poetry would make for a matter of rather pleasurable comment and would certainly not lower the general stand• ard of the book. I'll come back to these two or three poets presently, but let us first consider the question of New Zealand's prose writers. Ah yes, we have, or had, Kath• erine Mansfield, who died exactly fifty years ago. Her work is legendary — her Collected Stories (Constable) goes from reprint to reprint, and indeed, pirate printings are being shovelled off to the priting mills now that her fifty year copyright protection has run out. But Katherine Mansfield never was a "New Zealand writer" as such. She left early in the piece. But how did later writers fare, internationally speaking? It was Janet Frame who first wrote the long awaited "New Zealand Novel." Owls Do Cry was published in 1957. A rather cruel but incisive novel, about herself (everyone has one good novel in them), it centred on her own childhood experiences in Oamaru, a small town eighty miles north of Dunedin -— a town in which rough farmers drove sheep-shit-smelling American V-8 jalopies inexpertly down the main drag — where the local "bikies" as they are now called, grouped in vociferous RECENT NEW ZEALAND WRITING 17 bunches outside the corner milk bar. -

Newsletter – 15 April 2010 ISSN: 1178-9441

INTERNATIONAL INSTITUTE OF MODERN LETTERS Te P¯utahi Tuhi Auaha o te Ao Newsletter – 15 April 2010 ISSN: 1178-9441 This is the 154th in a series of occasional newsletters from the Victoria University centre of the International Institute of Modern Letters. For more information about any of the items, please email [email protected]. 1. Second trimester writing courses at the IIML ................................................... 2 2. Our first PhD ........................................................................................................ 2 3. Legend of a suicide author to appear in Wellington .......................................... 2 4. The Godfather comes to town .............................................................................. 3 5. From the whiteboard ............................................................................................ 3 6. Glyn Maxwell’s masterclass ................................................................................ 3 7. This and That ........................................................................................................ 3 8. Racing colours ....................................................................................................... 4 9. New Zealand poetry goes Deutsch ...................................................................... 4 10. Phantom poetry ................................................................................................. 5 11. Making something happen .............................................................................. -

Allegory in the Fiction of Janet Frame

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. ALLEGORY IN THE FICTION OF JANET FRAME A thesis in partial fulfIlment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English at Massey University. Judith Dell Panny 1991. i ABSTRACT This investigation considers some aspects of Janet Frame's fiction that have hitherto remained obscure. The study includes the eleven novels and the extended story "Snowman, Snowman". Answers to questions raised by the texts have been found within the works themselves by examining the significance of reiterated and contrasting motifs, and by exploring the most literal as well as the figurative meanings of the language. The study will disclose the deliberate patterning of Frame's work. It will be found that nine of the innovative and cryptic fictions are allegories. They belong within a genre that has emerged with fresh vigour in the second half of this century. All twelve works include allegorical features. Allegory provides access to much of Frame's irony, to hidden pathos and humour, and to some of the most significant questions raised by her work. By exposing the inhumanity of our age, Frame prompts questioning and reassessment of the goals and values of a materialist culture. Like all writers of allegory, she focuses upon the magic of language as the bearer of truth as well as the vehicle of deception. -

NP 2013.Docx

LISTE INTERNATIONALE DES NOMS PROTÉGÉS (également disponible sur notre Site Internet : www.IFHAonline.org) INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (also available on our Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) Fédération Internationale des Autorités Hippiques de Courses au Galop International Federation of Horseracing Authorities 15/04/13 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne, France Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org La liste des Noms Protégés comprend les noms : The list of Protected Names includes the names of : F Avant 1996, des chevaux qui ont une renommée F Prior 1996, the horses who are internationally internationale, soit comme principaux renowned, either as main stallions and reproducteurs ou comme champions en courses broodmares or as champions in racing (flat or (en plat et en obstacles), jump) F de 1996 à 2004, des gagnants des neuf grandes F from 1996 to 2004, the winners of the nine épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Japan Cup, Melbourne Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Queen Elizabeth II Stakes (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F à partir de 2005, des gagnants des onze grandes F since 2005, the winners of the eleven famous épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Cox Plate (2005), Melbourne Cup (à partir de 2006 / from 2006 onwards), Dubai World Cup, Hong Kong Cup, Japan Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Irish Champion (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F des principaux reproducteurs, inscrits à la F the main stallions and broodmares, registered demande du Comité International des Stud on request of the International Stud Book Books. -

PNZ 47 Digital Version

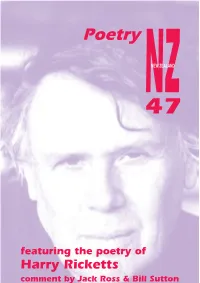

Poetry NZNEW ZEALAND 47 featuring the poetry of 1 Harry Ricketts comment by Jack Ross & Bill Sutton Poetry NZ Number 47, 2013 Two issues per year Editor: Alistair Paterson ONZM Submissions: Submit at any time with a stamped, self-addressed envelope (and an email address if available) to: Poetry NZ, 34B Methuen Road, Avondale, Auckland 0600, New Zealand or 1040 E. Paseo El Mirador, Palm Springs, CA 92262-4837, USA Please note that overseas submissions cannot be returned, and should include an email address for reply. Postal subscriptions: Poetry NZ, 37 Margot Street, Epsom, Auckland 1051, New Zealand or 1040 E. Paseo el Mirador, Palm Springs, CA 92262-4837, USA Postal subscription Rates: US Subscribers (by air) One year (2 issues) $30.00 $US24.00 Two years (4 issues) $55.00 $US45.00 Libraries: 1 year $32.00 $US25.00 Libraries: 2 years $60.00 $US46.00 Other countries One year (2 issues) $NZ36.00 Two years (4 issues) $NZ67.00 Online subscriptions: To take out a subscription go to www.poetrynz.net and click on ‘subscribe’. The online rates are listed on this site. When your subscription application is received it will be confi rmed by email, and your fi rst copy of the magazine will then be promptly posted out to you. 2 Poetry NZ 47 Alistair Paterson Editor Puriri Press & Brick Row Auckland, New Zealand Palm Springs, California, USA September 2013 3 ISSN 0114-5770 Copyright © 2013 Poetry NZ 37 Margot Street, Epsom, Auckland 1051, New Zealand All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo copying, recording or otherwise without the written permission of the publisher. -

From Acorn Stud Storm Bird Northern Dancer South Ocean Mujadil

From Acorn Stud 901 901 Northern Dancer Storm Bird South Ocean Mujadil (USA) Secretariat BAY FILLY (IRE) Vallee Secrete March 8th, 2004 Midou Lyphard Alzao Va Toujours Lady Rebecca (1987) Prince Regent French Princess Queen Dido E.B.F. Nominated. 1st dam VA TOUJOURS: 3 wins at 2 and 3 and £28,007 inc. Reference Point Strensall S., L., placed viz. 3rd Bottisham Heath Stud Rockfel S., Gr.3; dam of 4 previous foals; 3 runners; 3 winners: Polish Pilot (IRE) (95 g. by Polish Patriot (USA)): 4 wins, £30,203 viz. placed at 2; also 2 wins over hurdles and 2 wins over fences and placed 32 times. Dauphin (IRE) (93 g. by Astronef): 3 wins at 3 and 4 inc. Bollinger Champagne Challenge Series H., Ascot and placed 7 times. White Mountain (IRE) (02 c. by Monashee Mountain (USA)): 2 wins at 3, 2005. Thatjours (IRE) (96 f. by Thatching): unraced; dam of a winner: Somaly Mam (IRE): 2 wins at 2, 2004 in Italy and placed 3 times. 2nd dam FRENCH PRINCESS: 4 wins at 3 and 4 and placed; dam of 5 winners inc.: VA TOUJOURS (f. by Alzao (USA)): see above. French Flutter: 3 wins inc. winner at 3 and placed 5 times. Lady of Surana: unraced; dam of 9 winners inc.: Alriffa (IND): 13 wins in India placed 2nd Nanoli Stud Juvenile Million, L. and 3rd Kingfisher Mysore 2000 Guineas, L. 3rd dam QUEEN DIDO (by Acropolis): winner at 2 and placed; dam of 3 winners inc.: ALIA: 5 wins at 3 inc. Princess Royal S., Gr.3, placed; dam of 6 winners. -

Southampton and the Isle of Wight; a Poem in Four Books

8 THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES ... y^s=.v u^ A .*^ ^.'^r iJIa'"^ ?r^ ^^"^ SOUTHAMPTON AND THE ISLE OF WIGHT % ^oem IN FOUR BOOKS BY SAMUEL BROMLEY: AUTHOR OF "the LIFE OF CHRIST;" "SERMON ON THE DEATH OF DR. CHALMERS;" ETC. ETC. ETC. Sottti^ampton: PRINTED BY GEORGE L. MARSHALL, HDCCCXLIX. SOUTHAMPTON AND THE ISLE OF WIGHT: % ^oem. BOOK I . " Like as the waves make towards the pebbled shore, So do our minutes hasten to their end ; Each changing place with that which goes before, In sequent toil all forward do contend. Nativity once in the main of light Crawls to maturity, wherewith being crowned, Crooked eclipses 'gainst his glory fight, And time that gave, doth now his gift confound. Time doth transfix the flourish set on youth, delves the And parallels in beauties brow ; Feeds on the rarities of nature's truth, And nothing stands but for his scythe to mow. And yet to times in hope, my verse shall stand. Praising thy worth, despite his cruel hand." Shakespear, 872900 CONTENTS. BOOK I. CANTO I.—The Introduction. CANTO II.—The History of Southampton. CANTO III.—The History of Southampton continued. CANTO IV.—The History of Southampton concluded. BOOK II. CANTO I.—The Introduction. CANTO II.—The Complaint of an old Inhabitantof Southampton, who compares the present, with the past state of the Town. CANTO III.—The Queen's Visit to Wood Mill. BOOK III. CANTO I.—The Author's apology for poetising. CANTO II.—Navigation. The Sailing of one of the Oriental Steam Packets. CANTO III.—The Return of one of the Oriental Packets to the Mother Bank, and the Songs of the Jolly Sailors. -

Denis Glover

LA:J\(JJFA LL ' Zealam 'terly 'Y' and v.,,,.,,,,,,.,.,,," by 1 'On ,,'re CON'I'EN'TS Notes 3 City and Suburban, Frank Sargeson 4 Poems of the Mid-Sixties, K. 0. Arvidson, Peter Bland, Basil Dowling, Denis Glover, Paul Henderson, Kevin Ireland, Louis Johnson, Owen Leeming, Raymond Ward, Hubert Witheford, Mark Young 10 Artist, Michael Gifkins 33 Poems from the Panjabi, Amrita Pritam 36 Beginnings, Janet Frame 40 A Reading of Denis Glover, Alan Roddick 48 COMMENTARIES; Indian Letter, Mahendra Kulasrestha 58 Greer Twiss, Paul Beadle 63 After the Wedding, Kirsty Northcote-Bade 65 REVIEWS: A Walk on the Beach, Dennis McEldowney 67 The Cunninghams, Children of the Poor, K. 0. Arvidson 69 Bread and a Pension, MacD. P. Jackson 74 Wild Honey, J. E. P. T homson 83 Ambulando, R. L. P. Jackson 86 Byron the Poet, !an Jack 89 Studies of a Small Democracy, W. J. Gardner 91 Correspondence, W. K. Mcllroy, Lawrence Jones, Atihana Johns 95 Sculpture by Greer T wiss Cover design by V ere Dudgeon VOLUME NINETEEN NUMBER ONE MARCH 1965 LANDFALL is published with the aid of a grant from the New Zealand Literary Fund. LANDFALL is printed and published by The Caxton Press at 119 Victoria Street, Christchurch. The annual subscription is 20s. net post free, and should be sent to the above address. All contributions used will be paid for. Manuscripts should be sent to the editor at the above address; they cannot be returned unless accompanied by a stamped and addressed envelope. Notes PoETs themselves pass judgment on what they say by their way of saying it. -

London | 24 March 2021 March | 24 London

LONDON | 24 MARCH 2021 MARCH | 24 LONDON LONDON THE FAMILY COLLECTION OF THE LATE COUNTESS MOUNTBATTEN OF BURMA 24 MARCH 2021 L21300 AUCTION IN LONDON ALL EXHIBITIONS FREE 24 MARCH 2021 AND OPEN TO THE PUBLIC 10 AM Saturday 20 March 12 NOON–5 PM 34-35 New Bond Street Sunday 21 March London, W1A 2AA 12 NOON–5 PM +44 (0)20 7293 5000 sothebys.com Monday 22 March FOLLOW US @SOTHEBYS 10 AM–5 PM #SothebysMountbatten Tuesday 23 March 10 AM–5 PM TO LEARN MORE ABOUT THE PROPERTY IN THIS SALE, PLEASE VISIT This page SOTHEBYS.COM/L21300 LOT XXX UNIQUE COLLECTIONS SPECIALISTS ENQUIRIES FURNITURE & DECORATIVE ART MIDDLE EAST & INDIAN SALE NUMBER David Macdonald Alexandra Roy L21300 “BURM” [email protected] [email protected] +44 20 7293 5107 +44 20 7293 5507 BIDS DEPARTMENT Thomas Williams MODERN & POST-WAR BRITISH ART +44 (0)20 7293 5283 Mario Tavella Harry Dalmeny Henry House [email protected] Thomas Podd fax +44 (0)20 7293 6255 +44 20 7293 6211 Chairman, Sotheby’s Europe, Chairman, UK & Ireland Senior Director [email protected] [email protected] +44 20 7293 5497 Chairman Private European +44 (0)20 7293 5848 Head of Furniture & Decorative Arts ANCIENT SCULPTURE & WORKS Collections and Decorative Arts [email protected] +44 (0)20 7293 5486 OF ART Telephone bid requests should OLD MASTER PAINTINGS be received 24 hours prior +44 (0)20 7293 5052 [email protected] Florent Heintz Julian Gascoigne to the sale. This service is [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] offered for lots with a low estimate +44 20 7293 5526 +44 20 7293 5482 of £3,000 and above. -

![U DSG Papers of Howard Sergeant, Including [1930]-1995 the Archives of 'Outposts' Poetry Magazine](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4831/u-dsg-papers-of-howard-sergeant-including-1930-1995-the-archives-of-outposts-poetry-magazine-2844831.webp)

U DSG Papers of Howard Sergeant, Including [1930]-1995 the Archives of 'Outposts' Poetry Magazine

Hull History Centre: Howard Sergeant, inc 'Outposts' poetry magazine U DSG Papers of Howard Sergeant, including [1930]-1995 the Archives of 'Outposts' poetry magazine Biographical Background: Herbert ('Howard') Sergeant was born in Hull in 1914 and qualified as an accountant. He served in the RAF and the Air Ministry during the Second World War and with the assistance of his friend Lionel Monteith, edited and published the first issue of his poetry magazine 'Outposts' in February 1944. Outposts is the longest running independent poetry magazine in Britain. Sergeant had been writing poetry since childhood and his first poem to be published was 'Thistledown magic', in 'Chambers Journal' in 1943. 'Outposts' was conceived in wartime and its early focus was on poets 'who, by reason of the particular outposts they occupy, are able to visualise the dangers which confront the individual and the whole of humanity, now and after the war' (editorial, 'Outposts', no.1). Over the decades, the magazine specialised in publishing unrecognised poets alongside the well established. Sergeant deliberately avoided favouring any particular school of poetry, and edited 'Mavericks: an anthology', with Dannie Abse, in 1957, in support of this stance. Sergeant's own poetry was included in the first issue of 'Outposts' (but rarely thereafter) and his first published collection, 'The Leavening Air', appeared in 1946. He was involved in setting up the Dulwich Group (a branch of the British Poetry Association) in 1949, and again, when it re-formed in 1960. In 1956, Sergeant published the first of the Outposts Modern Poets Series of booklets and hardbacks devoted to individual poets. -

2020 International List of Protected Names

INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (only available on IFHA Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) International Federation of Horseracing Authorities 03/06/21 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne-Billancourt, France Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org The list of Protected Names includes the names of : Prior 1996, the horses who are internationally renowned, either as main stallions and broodmares or as champions in racing (flat or jump) From 1996 to 2004, the winners of the nine following international races : South America : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil Asia : Japan Cup, Melbourne Cup Europe : Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Queen Elizabeth II Stakes North America : Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf Since 2005, the winners of the eleven famous following international races : South America : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil Asia : Cox Plate (2005), Melbourne Cup (from 2006 onwards), Dubai World Cup, Hong Kong Cup, Japan Cup Europe : Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Irish Champion North America : Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf The main stallions and broodmares, registered on request of the International Stud Book Committee (ISBC). Updates made on the IFHA website The horses whose name has been protected on request of a Horseracing Authority. Updates made on the IFHA website * 2 03/06/2021 In 2020, the list of Protected -

RÍDAN the DEVIL and OTHER STORIES by Louis Becke

1 RÍDAN THE DEVIL AND OTHER STORIES By Louis Becke Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Company 1899 RÍDAN THE DEVIL Rídan lived alone in a little hut on the borders of the big German plantation at Mulifenua, away down at the lee end of Upolu Island, and every one of his brown-skinned fellow-workers either hated or feared him, and smiled when Burton, the American overseer, would knock him down for being a 'sulky brute.' But no one of them cared to let Rídan see him smile. For to them he was a wizard, a devil, who could send death in the night to those he hated. And so when anyone died on the plantation he was blamed, and seemed to like it. Once, when he lay ironed hand and foot in the stifling corrugated iron 'calaboose,' with his blood-shot eyes fixed in sullen rage on Burton's angered face, Tirauro, a Gilbert Island native assistant overseer, struck him on the mouth and called him 'a pig cast up by the ocean.' This was to please the white man. But it did not, for Burton, cruel as he was, called Tirauro a coward and felled him at once. By ill-luck he fell within reach of Rídan, and in another moment the manacled hands had seized his enemy's throat. For five minutes the three men struggled together, the white overseer beating Rídan over the head with the butt of his heavy Colt's pistol, and then when Burton rose to his feet the two brown men were lying motionless together; but Tirauro was dead.