A Literature Review and Life History Summary for Five Bivalve Molluscs Common to the Shoalwater Reservation and Willapa Bay, Washington

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

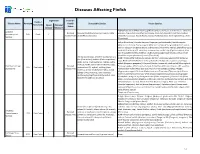

Diseases Affecting Finfish

Diseases Affecting Finfish Legislation Ireland's Exotic / Disease Name Acronym Health Susceptible Species Vector Species Non-Exotic Listed National Status Disease Measures Bighead carp (Aristichthys nobilis), goldfish (Carassius auratus), crucian carp (C. carassius), Epizootic Declared Rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss), redfin common carp and koi carp (Cyprinus carpio), silver carp (Hypophtalmichthys molitrix), Haematopoietic EHN Exotic * Disease-Free perch (Percha fluviatilis) Chub (Leuciscus spp), Roach (Rutilus rutilus), Rudd (Scardinius erythrophthalmus), tench Necrosis (Tinca tinca) Beluga (Huso huso), Danube sturgeon (Acipenser gueldenstaedtii), Sterlet sturgeon (Acipenser ruthenus), Starry sturgeon (Acipenser stellatus), Sturgeon (Acipenser sturio), Siberian Sturgeon (Acipenser Baerii), Bighead carp (Aristichthys nobilis), goldfish (Carassius auratus), Crucian carp (C. carassius), common carp and koi carp (Cyprinus carpio), silver carp (Hypophtalmichthys molitrix), Chub (Leuciscus spp), Roach (Rutilus rutilus), Rudd (Scardinius erythrophthalmus), tench (Tinca tinca) Herring (Cupea spp.), whitefish (Coregonus sp.), North African catfish (Clarias gariepinus), Northern pike (Esox lucius) Catfish (Ictalurus pike (Esox Lucius), haddock (Gadus aeglefinus), spp.), Black bullhead (Ameiurus melas), Channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus), Pangas Pacific cod (G. macrocephalus), Atlantic cod (G. catfish (Pangasius pangasius), Pike perch (Sander lucioperca), Wels catfish (Silurus glanis) morhua), Pacific salmon (Onchorhynchus spp.), Viral -

Shell Classification – Using Family Plates

Shell Classification USING FAMILY PLATES YEAR SEVEN STUDENTS Introduction In the following activity you and your class can use the same techniques as Queensland Museum The Queensland Museum Network has about scientists to classify organisms. 2.5 million biological specimens, and these items form the Biodiversity collections. Most specimens are from Activity: Identifying Queensland shells by family. Queensland’s terrestrial and marine provinces, but These 20 plates show common Queensland shells some are from adjacent Indo-Pacific regions. A smaller from 38 different families, and can be used for a range number of exotic species have also been acquired for of activities both in and outside the classroom. comparative purposes. The collection steadily grows Possible uses of this resource include: as our inventory of the region’s natural resources becomes more comprehensive. • students finding shells and identifying what family they belong to This collection helps scientists: • students determining what features shells in each • identify and name species family share • understand biodiversity in Australia and around • students comparing families to see how they differ. the world All shells shown on the following plates are from the • study evolution, connectivity and dispersal Queensland Museum Biodiversity Collection. throughout the Indo-Pacific • keep track of invasive and exotic species. Many of the scientists who work at the Museum specialise in taxonomy, the science of describing and naming species. In fact, Queensland Museum scientists -

Pathogens Table 2006

Important pathogens and parasites of molluscs Genetic and Pathology Laboratory Pathogen or parasite Host species Host impact Geographical distribution Infection period Diagnostic Cycle Species Group Denmark, Netherland, Incubation period : 3-4 month Ostrea edulis, O. Parasite of oyster haemocytes Throughout the year France, Ireland, Great Britain in infected area. Histology, Bonamia ostreae Protozoan Conchaphila, O. Angasi, O. (=>all the tissues can be invaded). (with a peak in Direct (except Scotland), Italy, tissue imprint, PCR, ISH, Puelchana, Tiostrea chilensis Oyster mortality September) Spain and USA electron microscopy Parasite of oyster haemocytes Throughout the year Histology, tissue imprint, Ostrea angasi, Ostrea Australia, New Zéland, Bonamia exitiosa Protozoan (=>all the tissues can be invaded). (with a peak during PCR, ISH, electron Unknown chilensis, Ostrea edulis Tasmania, Spain (in 2007) Oyster mortality Australian autumn) microscopy Parasites present in connective Histology, tissue imprint, Haplosporidium tissue (mantle, gonads, digestive Protozoan Crassostrea virginica USA, Canada Spring-summer PCR, ISH, electron Unknown costale gland) but not in digestive tubule microscopy epithelia. Mortality in May-June Parasites present in gills, connective tissue. Sporulation only Histology, tissue imprint, Unknown but Haplosporidium Crassostrea virginica, USA, Canada, Japan, Korea, Summer (May until Protozoan in the epithelium of digestive gland smear, PCR, HIS, electron intermediate host is nelsoni Crassostrea gigas France October) in C. virginica, Mortalities in C. microscopy suspected virginica. No mortality in C. gigas Parasite present in connective Haplosporidium Protozoan O. edulis, O. angasi tissue. Sometimes, mortality can France, Netherland, Spain Histology, tissue imprint Unknown armoricanum be observed Ostrea edulis , Tiostrea Spring-summer Histology, tissue imprint, ISH, Intermediate host: Extracellular parasite of the Marteilia refringens Protozoan chilensis, O. -

Marine Ecology Progress Series 502:219

The following supplement accompanies the article Spatial patterns in early post-settlement processes of the green sea urchin Strongylocentrotus droebachiensis L. B. Jennings*, H. L. Hunt Department of Biology, University of New Brunswick, PO Box 5050, Saint John, New Brunswick E2L 4L5, Canada *Corresponding author: [email protected] Marine Ecology Progress Series 502: 219–228 (2014) Supplement. Table S1. Average abundance of organisms in the cages for the with-suite treatments at the end of the experiment at the 6 sites in 2008 Birch Dick’s Minister’s Tongue Midjic Clark’s Cove Island Island Shoal Bluff Point Amphipod Corophium 38.5 37.5 21.5 21.6 52.1 40.7 Amphipod Gammaridean 1.4 1.8 3.8 16.2 19.8 16.4 Amphipod sp. 0.5 0.4 0.0 0.0 0.1 0.0 Amphiporus angulatus 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.2 0.1 Amphitrite cirrata 0.0 0.0 0.1 0.0 0.0 0.0 Amphitrite ornata 0.1 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Anenome sp. 1 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.4 0.3 0.0 Anenome sp. 2 0.0 0.1 0.3 0.0 0.0 3.7 Anomia simplex 47.6 28.7 25.2 25.2 10.3 10.4 Anomia squamula 3.2 1.6 0.8 1.1 0.1 0.2 Arabellid unknown 0.0 0.1 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.1 Ascidian sp. 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.1 0.0 0.0 Astarte sp. -

Geological Survey

DEPABTMENT OF THE INTEKIOR BULLETIN OF THE UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY N~o. 151 WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1898 UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CHARLES D. WALCOTT, DIEECTOR THE LOWER CRETACEOUS GRYPMAS OF THK TEX.AS REGION ROBERT THOMAS HILL THOMAS WAYLA'ND VAUGHAN WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT FEINTING OFFICE 18.98 THE LOWER CRETACEOUS GRYPHJ1AS OF THE TEXAS REGION. BY I EOBEET THOMAS HILL and THOMAS WAYLAND VAUGHAN. CONTENTS. Page. Letter of transmittal....._..........._....._ ............................ 11 Introduction ...---._._....__................._....._.__............._...._ 13 The fossil oysters of the Texas region.._._.._.___._-..-._._......-..--.... 23 Classification of the Ostreidae. .. ...-...---..-.......-.....-.-............ 24 Historical statement of the discovery in the Texas region of the forms referred to Gryphsea pitcher! Morton ................................ 33 Gryphaea corrugata Say._______._._..__..__...__.,_._.________...____.._ 33 Gryphsea pitcheri Morton............................................... 34 Roemer's Gryphsea pitcheri............................................ 35 Marcou's Gryphsea pitcheri............................................ 35 Blake's Gryphaea pitcheri............................................. 36 Schiel's Gryphsea pitcheri...........................,.:................ 36 Hall's Gryphsea pitcheri (= G. dilatata var. tucumcarii Marcou) ...... 36 Heilprin's Gryphaea pitcheri.....'..................................... 37 Gryphaea pitcheri var. hilli Cragin................................... -

Ripiro Beach

http://researchcommons.waikato.ac.nz/ Research Commons at the University of Waikato Copyright Statement: The digital copy of this thesis is protected by the Copyright Act 1994 (New Zealand). The thesis may be consulted by you, provided you comply with the provisions of the Act and the following conditions of use: Any use you make of these documents or images must be for research or private study purposes only, and you may not make them available to any other person. Authors control the copyright of their thesis. You will recognise the author’s right to be identified as the author of the thesis, and due acknowledgement will be made to the author where appropriate. You will obtain the author’s permission before publishing any material from the thesis. The modification of toheroa habitat by streams on Ripiro Beach A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science (Research) in Environmental Science at The University of Waikato by JANE COPE 2018 ―We leave something of ourselves behind when we leave a place, we stay there, even though we go away. And there are things in us that we can find again only by going back there‖ – Pascal Mercier, Night train to London i Abstract Habitat modification and loss are key factors driving the global extinction and displacement of species. The scale and consequences of habitat loss are relatively well understood in terrestrial environments, but in marine ecosystems, and particularly soft sediment ecosystems, this is not the case. The characteristics which determine the suitability of soft sediment habitats are often subtle, due to the apparent homogeneity of sandy environments. -

Shellfish Reefs at Risk

SHELLFISH REEFS AT RISK A Global Analysis of Problems and Solutions Michael W. Beck, Robert D. Brumbaugh, Laura Airoldi, Alvar Carranza, Loren D. Coen, Christine Crawford, Omar Defeo, Graham J. Edgar, Boze Hancock, Matthew Kay, Hunter Lenihan, Mark W. Luckenbach, Caitlyn L. Toropova, Guofan Zhang CONTENTS Acknowledgments ........................................................................................................................ 1 Executive Summary .................................................................................................................... 2 Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 6 Methods .................................................................................................................................... 10 Results ........................................................................................................................................ 14 Condition of Oyster Reefs Globally Across Bays and Ecoregions ............ 14 Regional Summaries of the Condition of Shellfish Reefs ............................ 15 Overview of Threats and Causes of Decline ................................................................ 28 Recommendations for Conservation, Restoration and Management ................ 30 Conclusions ............................................................................................................................ 36 References ............................................................................................................................. -

Tracking Larval, Newly Settled, and Juvenile Red Abalone (Haliotis Rufescens ) Recruitment in Northern California

Journal of Shellfish Research, Vol. 35, No. 3, 601–609, 2016. TRACKING LARVAL, NEWLY SETTLED, AND JUVENILE RED ABALONE (HALIOTIS RUFESCENS ) RECRUITMENT IN NORTHERN CALIFORNIA LAURA ROGERS-BENNETT,1,2* RICHARD F. DONDANVILLE,1 CYNTHIA A. CATTON,2 CHRISTINA I. JUHASZ,2 TOYOMITSU HORII3 AND MASAMI HAMAGUCHI4 1Bodega Marine Laboratory, University of California Davis, PO Box 247, Bodega Bay, CA 94923; 2California Department of Fish and Wildlife, Bodega Bay, CA 94923; 3Stock Enhancement and Aquaculture Division, Tohoku National Fisheries Research Institute, FRA 3-27-5 Shinhamacho, Shiogama, Miyagi, 985-000, Japan; 4National Research Institute of Fisheries and Environment of Inland Sea, Fisheries Agency of Japan 2-17-5 Maruishi, Hatsukaichi, Hiroshima 739-0452, Japan ABSTRACT Recruitment is a central question in both ecology and fisheries biology. Little is known however about early life history stages, such as the larval and newly settled stages of marine invertebrates. No one has captured wild larval or newly settled red abalone (Haliotis rufescens) in California even though this species supports a recreational fishery. A sampling program has been developed to capture larval (290 mm), newly settled (290–2,000 mm), and juvenile (2–20 mm) red abalone in northern California from 2007 to 2015. Plankton nets were used to capture larval abalone using depth integrated tows in nearshore rocky habitats. Newly settled abalone were collected on cobbles covered in crustose coralline algae. Larval and newly settled abalone were identified to species using shell morphology confirmed with genetic techniques using polymerase chain reaction restriction fragment length polymorphism with two restriction enzymes. Artificial reefs were constructed of cinder blocks and sampled each year for the presence of juvenile red abalone. -

Data From: Microplastic Concentrations in Two Oregon Bivalve Species: Spatial, Temporal, and Species Variability

Portland State University PDXScholar Environmental Science and Management Datasets Environmental Science and Management 7-2019 Data From: Microplastic Concentrations in Two Oregon Bivalve Species: Spatial, Temporal, and Species Variability Britta Baechler Portland State University, [email protected] Elise F. Granek Portland State University, [email protected] Matthew V. Hunter Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife Kathleen E. Conn United States Geological Survey Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/esm_data Part of the Environmental Health and Protection Commons, Environmental Indicators and Impact Assessment Commons, and the Environmental Monitoring Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Baechler, Britta; Granek, Elise F.; Hunter, Matthew V.; and Conn, Kathleen E., "Microplastic Concentrations in Two Oregon Bivalve Species: Spatial, Temporal, and Species Variability" (2019). [Dataset]. https://doi.org/10.15760/esm-data.1 This Dataset is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Environmental Science and Management Datasets by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Metadata template1 for datasets of L&O-Letters articles Table 1. Description of the fields needed to describe the creation of your dataset. Title of dataset Microplastic Concentrations in Two Oregon Bivalve Species: Spatial, Temporal, and Species Variability URL of dataset Data is available in the Portland State University PDXScholar data repository at: https://doi.org/10.15760/esm-data.1 Abstract Microplastics are an ecological stressor with implications for ecosystem and human health when present in seafood. -

The Malacological Society of London

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This meeting was made possible due to generous contributions from the following individuals and organizations: Unitas Malacologica The program committee: The American Malacological Society Lynn Bonomo, Samantha Donohoo, The Western Society of Malacologists Kelly Larkin, Emily Otstott, Lisa Paggeot David and Dixie Lindberg California Academy of Sciences Andrew Jepsen, Nick Colin The Company of Biologists. Robert Sussman, Allan Tina The American Genetics Association. Meg Burke, Katherine Piatek The Malacological Society of London The organizing committee: Pat Krug, David Lindberg, Julia Sigwart and Ellen Strong THE MALACOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF LONDON 1 SCHEDULE SUNDAY 11 AUGUST, 2019 (Asilomar Conference Center, Pacific Grove, CA) 2:00-6:00 pm Registration - Merrill Hall 10:30 am-12:00 pm Unitas Malacologica Council Meeting - Merrill Hall 1:30-3:30 pm Western Society of Malacologists Council Meeting Merrill Hall 3:30-5:30 American Malacological Society Council Meeting Merrill Hall MONDAY 12 AUGUST, 2019 (Asilomar Conference Center, Pacific Grove, CA) 7:30-8:30 am Breakfast - Crocker Dining Hall 8:30-11:30 Registration - Merrill Hall 8:30 am Welcome and Opening Session –Terry Gosliner - Merrill Hall Plenary Session: The Future of Molluscan Research - Merrill Hall 9:00 am - Genomics and the Future of Tropical Marine Ecosystems - Mónica Medina, Pennsylvania State University 9:45 am - Our New Understanding of Dead-shell Assemblages: A Powerful Tool for Deciphering Human Impacts - Sue Kidwell, University of Chicago 2 10:30-10:45 -

Environmental History and Oysters at Point Reyes National Seashore

Restoring the Past: Environmental History and Oysters at Point Reyes National Seashore Timothy Babalis Since its inception more than 40 years ago, environmental history has matured into a respected, if somewhat nebulous, discipline in academic circles but has so far received less attention within public land management agencies such as the National Park Service.1 This is unfortunate, because environmental history can provide information of great practical interest to resource managers as well as offering a valuable perspective on management prac- tices. The singular characteristic which distinguishes environmental history from other his- torical methodologies is the acknowledgement that history happens in places. Like geogra- phers, whose field is closely related, environmental historians consider the spatial dimension of history to be just as important as its temporal. As a result, the physical environment is one of environmental history’s principal subjects, along with the usual human actors, political events, and cultural expressions of traditional history. But environmental history also acknowledges the active capacity of the environment to influence and form human history,as well as being the place where that history unfolds. Environmental historians study the recip- rocal relationship between human societies and the physical environments they inhabit. As one prominent environmental historian has written, “When I use the term ‘environmental history,’I mean specifically the history of the consequences of human actions on the environ- ment and the reciprocal consequences of an altered nature for human society.”2 While most environmental historians agree on this basic formula, the field quickly diverges in a bewildering number of directions and becomes increasingly difficult to catego- rize or define. -

Diarrhetic Shellfish Toxins and Other Lipophilic Toxins of Human Health Concern in Washington State

Mar. Drugs 2013, 11, 1-x manuscripts; doi:10.3390/md110x000x OPEN ACCESS Marine Drugs ISSN 1660-3397 www.mdpi.com/journal/marinedrugs Article Diarrhetic Shellfish Toxins and Other Lipophilic Toxins of Human Health Concern in Washington State Vera L. Trainer 1,*, Leslie Moore 1, Brian D. Bill 1, Nicolaus G. Adams 1, Neil Harrington 2, Jerry Borchert 3, Denis A.M. da Silva 1 and Bich-Thuy L. Eberhart 1 1 Marine Biotoxins Program, Environmental Conservation Division, Northwest Fisheries Science Center, National Marine Fisheries Service, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, 2725 Montlake Blvd. E, Seattle, WA 98112, USA; E-Mails: [email protected] (L.M.); [email protected] (B.D.B.); [email protected] (N.G.A.); [email protected] (D.A.M.D.S.); [email protected] (B.-T.L.E.) 2 Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe, 1033 Old Blyn Highway, Sequim, WA 98392, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] 3 Office of Shellfish and Water Protection, Washington State Department of Health, 111 Israel Rd SE, Tumwater, WA 98504, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-206-860-6788; Fax: +1-206-860-3335. Received: 13 March 2013; in revised form: 7 April 2013 / Accepted: 23 April 2013 / Published: Abstract: The illness of three people in 2011 after their ingestion of mussels collected from Sequim Bay State Park, Washington State, USA, demonstrated the need to monitor diarrhetic shellfish toxins (DSTs) in Washington State for the protection of human health.