Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

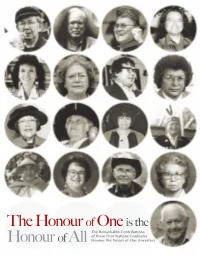

The Honour of One Is the the Remarkable Contributions of These First Nations Graduates Honour of All Honour the Voices of Our Ancestors Table of Contents of Table

The Honour of One is the The Remarkable Contributions of these First Nations Graduates Honour of All Honour the Voices of Our Ancestors 2 THE HONOUR OF ONE Table of Contents 3 Table of Contents 2 THE HONOUR OF ONE Introduction 4 William (Bill) Ronald Reid 8 George Manuel 10 Margaret Siwallace 12 Chief Simon Baker 14 Phyllis Amelia Chelsea 16 Elizabeth Rose Charlie 18 Elijah Edward Smith 20 Doreen May Jensen 22 Minnie Elizabeth Croft 24 Georges Henry Erasmus 26 Verna Jane Kirkness 28 Vincent Stogan 30 Clarence Thomas Jules 32 Alfred John Scow 34 Robert Francis Joseph 36 Simon Peter Lucas 38 Madeleine Dion Stout 40 Acknowledgments 42 4 THE HONOUR OF ONE IntroductionIntroduction 5 THE HONOUR OF ONE The Honour of One is the Honour of All “As we enter this new age that is being he Honour of One is the called “The Age of Information,” I like to THonour of All Sourcebook is think it is the age when healing will take a tribute to the First Nations men place. This is a good time to acknowledge and women recognized by the our accomplishments. This is a good time to University of British Columbia for share. We need to learn from the wisdom of their distinguished achievements and our ancestors. We need to recognize the hard outstanding service to either the life work of our predecessors which has brought of the university, the province, or on us to where we are today.” a national or international level. Doreen Jensen May 29, 1992 This tribute shows that excellence can be expressed in many ways. -

Indigenous Peoples' Rights in International

INDIGENOUS PEOPLES’ RIGHTS IN INTERNATIONAL LAW: INDIGENOUS PEOPLES’ RIGHTS EMERGENCE AND APPLICATION This diverse collection of essays and articles emerged from a workshop IN INTERNATIONAL LAW held in Oslo in March 2012, hosted by the Norwegian Center for Human Rights and the University of Oslo. The purpose of the workshop was to gather memories of how the international community had decided to exa- mine the situation of Indigenous peoples, to explore, explain and celebrate their pioneering work within the United Nations and the International La- bour Organization. The participants also examined the impact of that work and were further asked to identify desirable future developments. EMERGENCE AND APPLICATION The workshop and now this volume have brought together unique hi- storical and political perspectives of the same events from a variety of dif- ferent viewpoints. Participants were drawn from Indigenous communities, from the United Nations and the ILO, from national governments and from NGOs, all of whom had been involved in these discussions over the years – some since the very beginning. Among the participants in the workshop was Asbjørn Eide, the fou- nding Chairperson of the UN Working Group on Indigenous Populations (WGIP), and this book is dedicated to him on the occasion of his 80th birthday. Cover design by Holly Nordlum, Iñupiaq Artist RESOURCE CENTRE FOR THE RIGHTS OF INDIGENOUS PEOPLES EMERGENCE AND APPLICATION A book in honor of Asbjørn Eide at eighty INTERNATIONAL LAW: INDIGENOUS PEOPLES’ RIGHTS IN INTERNATIONAL WORK -

Sea Change the Birth of a New Marine Institute

ET LABORE MAGAZINE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF AUCKLAND SPRING 2004 SEA CHANGE THE BIRTH OF A NEW MARINE INSTITUTE SELLING OUR EXPERTISE TOP TERTIARY TEACHERS MAINTAINING THE BRAIN WHAT DRIVES OUR DONORS? Be in to win an objet d’art with your new home loan. And a trip around the world to find it. Buying a home is one of the most exciting purchases you will ever make but it can also be one of the most overwhelming. Fixed or floating, one year or two? There are so many decisions to make and so many choices – how do you know what is best for your personal circumstances? At HSBC we draw on our worldwide resources and local knowledge to help you choose the right home loan for you. We recognise that everyone is different and therefore offer a flexible choice of options at extremely competitive rates that can be tailored to your individual needs. To celebrate your individuality we’re offering you the chance to enter a draw to choose an objet d’art that’s uniquely you and a trip around the world to find it – when you select your new home loan and draw it down by 28 February 2005. For a competition entry form and more details - HSB 2827 Visit your nearest branch 0800 88 86 86 www.hsbc.co.nz Issued by The Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation Limited, incorporated in Hong Kong, New Zealand branch. Lending criteria and terms and conditions apply to all our home loans (including a minimum home loan value). Lenders Mortgage Insurance or an application fee may apply where you are borrowing more than 80% of a property’s value. -

Introduction One Setting the Stage

Notes Introduction 1. For further reference, see, for example, MacKay 2002. 2. See also Engle 2010 for this discussion. 3. I owe thanks to Naomi Kipuri, herself an indigenous Maasai, for having told me of this experience. 4. In the sense as this process was first described and analyzed by Fredrik Barth (1969). 5. An in-depth and updated overview of the state of affairs is given by other sources, such as the annual IWGIA publication, The Indigenous World. 6. The phrase refers to a 1972 cross-country protest by the Indians. 7. Refers to the Act that extinguished Native land claims in almost all of Alaska in exchange for about one-ninth of the state’s land plus US$962.5 million in compensation. 8. Refers to the court case in which, in 1992, the Australian High Court for the first time recognized Native title. 9. Refers to the Berger Inquiry that followed the proposed building of a pipeline from the Beaufort Sea down the Mackenzie Valley in Canada. 10. Settler countries are those that were colonized by European farmers who took over the land belonging to the aboriginal populations and where the settlers and their descendents became the majority of the population. 11. See for example Béteille 1998 and Kuper 2003. 12. I follow the distinction as clarified by Jenkins when he writes that “a group is a collectivity which is meaningful to its members, of which they are aware, while a category is a collectivity that is defined according to criteria formu- lated by the sociologist or anthropologist” (2008, 56). -

Albanian Families' History and Heritage Making at the Crossroads of New

Voicing the stories of the excluded: Albanian families’ history and heritage making at the crossroads of new and old homes Eleni Vomvyla UCL Institute of Archaeology Thesis submitted for the award of Doctor in Philosophy in Cultural Heritage 2013 Declaration of originality I, Eleni Vomvyla confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Signature 2 To the five Albanian families for opening their homes and sharing their stories with me. 3 Abstract My research explores the dialectical relationship between identity and the conceptualisation/creation of history and heritage in migration by studying a socially excluded group in Greece, that of Albanian families. Even though the Albanian community has more than twenty years of presence in the country, its stories, often invested with otherness, remain hidden in the Greek ‘mono-cultural’ landscape. In opposition to these stigmatising discourses, my study draws on movements democratising the past and calling for engagements from below by endorsing the socially constructed nature of identity and the denationalisation of memory. A nine-month fieldwork with five Albanian families took place in their domestic and neighbourhood settings in the areas of Athens and Piraeus. Based on critical ethnography, data collection was derived from participant observation, conversational interviews and participatory techniques. From an individual and family group point of view the notion of habitus led to diverse conceptions of ethnic identity, taking transnational dimensions in families’ literal and metaphorical back- and-forth movements between Greece and Albania. -

2013 Annual Report

2013 ANNUAL REPORT PETER WALL INSTITUTE FOR ADVANCED STUDIES The Institute is committed foremost to excellence in research; its goal is to stimulate collaborative, creative, innovative interdisciplinary research that makes important advances in knowledge. A guiding principle is that excellence and truly innovative research are achieved in a highly collaborative international research environment at the University of British Columbia, where UBC scholars have sustained opportunity to exchange ideas with national and international scholars, to work together on innovative research, develop new thinking that is beyond disciplinary boundaries, and engage in intellectual risk-taking. The Institute respects diversity of perspectives and backgrounds, research embedded in the community and integration of multimodal and expressive arts as an important component of research across all disciplines. The Institute is committed to wise stewardship of its resources in continuing to build on its significant research accomplishments. TABLE OF CONTENTS 04 Message from the Director 06 UBIAS Conference INTERNATIONAL PROGRAMS 10 International Visiting Research Scholar 14 UBC Visiting Scholar Abroad 18 International Research Roundtables 28 International Distinguished Visiting Professors 32 International Partnerships 36 Major Thematic Grant 39 French Lecture Series 40 Exploratory Workshops NATIONAL PROGRAMS 44 Peter Wall Distinguished Professor 48 Distinguished Scholars in Residence 54 Early Career Scholars 64 The Wall Exchange 66 The Wall Hour 70 Associate Research Fora 74 Theme Development Workshop 76 Research Mentoring Program 78 Colloquia 79 Special Events PETER WALL SOLUTIONS INITIATIVE 80 Program Review and Highlights ABOUT THE INSTITUTE 84 Funding and Governance 86 Committies 88 The Institute 90 Director and Staff Director’s Message Excellence in research is the Institute’s primary goal, creating the environment for collaborative, creative, interdisciplinary research that makes important advances in knowledge. -

RARE BOOK AUCTION Wednesday 24Th August 2011 11

RARE BOOK AUCTION Wednesday 24th August 2011 11 68 77 2 293 292 267 54 276 25 Rare Books, Maps, Ephemera and Early Photographs AUCTION: Wednesday 24th August, 2011, at 12 noon, 3 Abbey Street, Newton, Auckland VIEWING TIMES CONTACT Sunday 21st August 11.00am - 3.00 pm All inquiries to: Monday 22nd August 9.00am - 5.00pm Pam Plumbly - Rare book Tuesday 23rd August 9.00am - 5.00pm consultant at Art+Object Wednesday 24th August - viewing morning of sale. Phones - Office 09 378 1153, Mobile 021 448200 BUYER’S PREMIUM Art + Object 09 354 4646 Buyers shall pay to Pam Plumbly @ART+OBJECT 3 Abbey St, Newton, a premium of 17% of the hammer price plus GST Auckland. of 15% on the premium only. www.artandobject.co.nz Front cover features an illustration from Lot 346, Beardsley Aubrey, James Henry et al; The Yellow Book The Pycroft Collection of Rare New Zealand, Australian and Pacific Books 3rd & 4th November 2011 ART+OBJECT is pleased to announce the sale of the last great New Zealand library still remaining in private hands. Arthur Thomas Pycroft (1875 – 1971) a dedicated naturalist, scholar, historian and conservationist assembled the collection over seven decades. Arthur Pycroft corresponded with Sir Walter Buller. He was extremely well informed and on friendly terms with all the leading naturalists and museum directors of his era. This is reflected in the sheer scope of his collecting and an acutely sensitive approach to acquisitions. The library is rich in rare books and pamphlets, associated with personalities who shaped early New Zealand history. -

Indigenous New Zealand Literature in European Translation

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Open Journal Systems at the Victoria University of Wellington Library A History of Indigenous New Zealand Books in European Translation OLIVER HAAG Abstract This article is concerned with the European translations of Indigenous New Zealand literature. It presents a statistical evaluation of a bibliography of translated books and provides an overview of publishing this literature in Europe. The bibliography highlights some of the trends in publishing, including the distribution of languages and genres. This study offers an analysis of publishers involved in the dissemination of the translations and retraces the reasons for the proliferation of translated Indigenous books since the mid-1980s. It identifies Indigenous films, literary prizes and festivals as well as broader international events as central causes for the increase in translations. The popular appeal of Indigenous literature of Aotearoa/New Zealand has increased significantly over the last three decades. The translation of Indigenous books and their subsequent emergence in continental European markets are evidence of a perceptible change from a once predominantly local market to a now increasingly globally read and published body of literature. Despite the increase in the number of translations, however, little scholarship has been devoted to the history of translated Indigenous New Zealand literature.1 This study addresses that lack of scholarship by retracing the history of European translations of this body of literature and presenting extensive reference data to facilitate follow-up research. Its objective is to present a bibliography of translated books and book chapters and a statistical evaluation based on that bibliography. -

Manawa Whenua, Wē Moana Uriuri, Hōkikitanga Kawenga from the Heart of the Land, to the Depths of the Sea; Repositories of Knowledge Abound

TE TUMU SCHOOL OF MĀORI, PACIFIC & INDIGENOUS STUDIES Manawa whenua, wē moana uriuri, hōkikitanga kawenga From the heart of the land, to the depths of the sea; repositories of knowledge abound ___________________________________________________________________________ Te Papa Hou is a trusted digital repository providing for the long-term preservation and free access to leading scholarly works from staff and students at Te Tumu, School of Māori, Pacific and Indigenous Studies at the University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand. The information contained in each item is available for normal academic purposes, provided it is correctly and sufficiently referenced. Normal copyright provisions apply. For more information regarding Te Papa Hou please contact [email protected] ___________________________________________________________________________ Author: Professor Michael P.J Reilly Title: A Stranger to the Islands: voice, place and the self in Indigenous Studies Year: 2009 Item: Inaugural Professorial Lecture Venue: University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand http://eprintstetumu.otago.ac.nz Inaugural Professorial Lecture A Stranger to the Islands: voice, place and the self in Indigenous Studies Michael P.J. Reilly Tēnā koutou katoa, Kia orana kōtou katoatoa, Tangi kē, Welcome and Good Evening. This lecture presents the views of someone anthropologists call a participant-observer, and Māori characterise as a Pākehā, a manuhiri (guest, visitor), or a tangata kē (stranger); the latter two terms contrast with the permanence of the indigenous people, the tangata whenua (people of the land). All of us in this auditorium affiliate to one of these two categories, tangata kē and tangata whenua; sometimes to both. We are all inheritors of a particular history of British colonisation that unfolded within these lands from the 1800s (a legacy that Hone Tuwhare describes as ‘Victoriana-Missionary fog hiding legalized land-rape / and gentlemen thugs’).1 This legalized violation undermined the hospitality and respect assumed between tangata whenua and tangata kē. -

Our Outcomes Journey

TE WHĀNAU O WAIPAREIRA l ANNUAL REPORT 2015 -2016 2 #FUTUREMAKERS OUR OUTCOMES JOURNEY - TE WHĀ NAU O WAIPAREIRA #FUTUREMAKERS PERFORMANCE SUMMARY - l Annual Report 2015 – 2016 l Te Rārangi Upoko CONTENTS HE MIHI 2 NGĀ HUA O MATAORA OUR MATAORA OUTCOMES FRAMEWORK 2 OUTCOMES MEASUREMENT PILOT PĒPI AND TAMARIKI SERVICES 3 OUR WHĀNAU 5 6 OUR TAMARIKI 5 7 KORURE WHĀNAU – WHĀNAU TRANSFORMATION 8 REPORTING ON OUTCOMES 10 RANGATAHI OUTCOMES 11 OUR TAITAMARIKI SPEAK UP 12 SUPPORTING KORURE WHĀNAU - LIST OF SERVICES 14 HĀPORI MOMOHO - THRIVING COMMUNITIES 16 TE KĀHUI ORA O TĀMAKI COLLECTIVE IMPACT ACROSS THE TĀMAKI REGION 17 CRITICAL PARTNERSHIPS 20 SOCIAL VALUE AOTEAROA 20 HĀPAI TE HAUORA 21 WAITEMATA DISTRICT HEALTH BOARD 22 #FUTUREMAKERS MANA MĀORI 22 URBAN MAORI ADVANCEMENT NUMA 23 TE POU MATAKANA 25 WHĀNAU TAHI 27 DIRECTORY 28 OUR OUTCOMES JOURNEY - l Annual Report 2015 – 2016 l 1 He Mihi GREETINGS OUR MATAORA noho ana au ki te tara Waiatarua Ka hoki ngā whakaaro ki te wā o mua OUTCOMES FRAMEWORK EKi wana ki te wehi o ngā iwi Māori Ūhia ngā kanohi kei raro te whenua o te awa e are accountable to those that have papaku come before us, our communities and our Te waitohitohia rangatira ka roaka te ingoa Wwhānau. In 2013 we acknowledged this Waipareira! responsibility and laid out our vision for whānau in the “Whānau Future Makers, A 25 Year Outlook Ko te wehi ki a Ihowa ora o ngā mano. Kia Strategic Plan” māturuturu te tōmairangi o tōnā nui o tōnā atawhai ki runga i a tātau katoa. -

New Zealanders on the Net Discourses of National Identities In

New Zealanders on the Net Discourses of National Identities in Cyberspace Philippa Karen Smith A thesis submitted to Auckland University of Technology in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) 2012 Institute of Culture, Discourse & Communication School of Language and Culture ii Table of Contents List of Figures .............................................................................................................................. v List of Tables ............................................................................................................................... v List of Acronyms ........................................................................................................................ vi Attestation of Authorship ......................................................................................................... vii Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................. viii Abstract ....................................................................................................................................... ix Chapter One : Identifying the problem: a ‘new’ identity for New Zealanders? ................... 1 1.1 Setting the context ............................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 New Zealand in a globalised world .................................................................................................... -

This Online Version of the Thesis Uses Different Fonts from the Printed Version Held in Griffith University Library, and the Pagination Is Slightly Different

NOTE: This online version of the thesis uses different fonts from the printed version held in Griffith University Library, and the pagination is slightly different. The content is otherwise exactly the same. Journeys into a Third Space A study of how theatre enables us to interpret the emergent space between cultures Janinka Greenwood M.A., Dip Ed, Dip Tchg, Dip TESL This thesis is submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 1999 Statement This work has not been previously submitted for a degree or diploma in any university, To the best of my knowledge and belief, the thesis contains no material previously published or written by another person except where due reference is made in the thesis itself. Janinka Greenwood 17 December 1999 Acknowledgments Thanks are due to a number of people who have given me support and encouragement in completing this thesis. Firstly I am very grateful for the sustained encouragement and scholarly challenges given by my principal supervisor Associate Professor John O’Toole and also by my co-supervisor Dr Philip Taylor. I appreciate not only their breadth of knowledge in the field of drama, but also their courageous entry into a territory of cultural differences and their insistence that I make explicit cultural concepts that I had previously taken for granted. I am grateful also to Professor Ranginui Walker who, at a stage of the research when I felt the distance between Australia and New Zealand, consented to “look over my shoulder”. Secondly, my sincere thanks go to all those who shared information, ideas and enthusiasms with me during the interviews that are reported in this thesis and to the student teachers who explored with me the drama project that forms the final stage of the study.