Rigor Or Rigor Mortis? Stephen M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Theory of War and Peace: Theories and Cases COURSE TITLE 2

Ilia State University Faculty of Arts and Sciences MA Level Course Syllabus 1. Theory of War and Peace: Theories and Cases COURSE TITLE 2. Spring Term COURSE DURATION 3. 6.0 ECTS 4. DISTRIBUTION OF HOURS Contact Hours • Lectures – 14 hours • Seminars – 12 hours • Midterm Exam – 2 hours • Final Exam – 2 hours • Research Project Presentation – 2 hours Independent Work - 118 hours Total – 150 hours 5. Nino Pavlenishvili INSTRUCTOR Associate Professor, PhD Ilia State University Mobile: 555 17 19 03 E-mail: [email protected] 6. None PREREQUISITES 7. Interactive lectures, topic-specific seminars with INSTRUCTION METHODS deliberations, debates, and group discussions; and individual presentation of the analytical memos, and project presentation (research paper and PowerPoint slideshow) 8. Within the course the students are to be introduced to COURSE OBJECTIVES the vast bulge of the literature on the causes of war and condition of peace. We pay primary attention to the theory and empirical research in the political science and international relations. We study the leading 1 theories, key concepts, causal variables and the processes instigating war or leading to peace; investigate the circumstances under which the outcomes differ or are very much alike. The major focus of the course is o the theories of interstate war, though it is designed to undertake an overview of the literature on civil war, insurgency, terrorism, and various types of communal violence and conflict cycles. We also give considerable attention to the methodology (qualitative/quantitative; small-N/large-N, Case Study, etc.) utilized in the well- known works of the leading scholars of the field and methodological questions pertaining to epistemology and research design. -

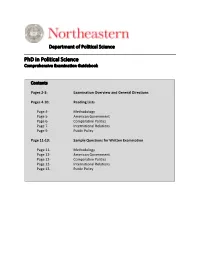

Phd in Political Science Comprehensive Examination Guidebook

Department of Political Science __________________________________________________________ PhD in Political Science Comprehensive Examination Guidebook Contents Pages 2-3: Examination Overview and General Directions Pages 4-10: Reading Lists Page 4- Methodology Page 5- American Government Page 6- Comparative Politics Page 7- International Relations Page 9- Public Policy Page 11-13: Sample Questions for Written Examination Page 11- Methodology Page 12- American Government Page 12- Comparative Politics Page 12- International Relations Page 13- Public Policy EXAMINATION OVERVIEW AND GENERAL DIRECTIONS Doctoral students sit For the comprehensive examination at the conclusion of all required coursework, or during their last semester of coursework. Students will ideally take their exams during the fifth semester in the program, but no later than their sixth semester. Advanced Entry students are strongly encouraged to take their exams during their Fourth semester, but no later than their FiFth semester. The comprehensive examination is a written exam based on the literature and research in the relevant Field of study and on the student’s completed coursework in that field. Petitioning to Sit for the Examination Your First step is to petition to participate in the examination. Use the Department’s graduate petition form and include the following information: 1) general statement of intent to sit For a comprehensive examination, 2) proposed primary and secondary Fields areas (see below), and 3) a list or table listing all graduate courses completed along with the Faculty instructor For the course and the grade earned This petition should be completed early in the registration period For when the student plans to sit For the exam. -

In Search of Democratic Peace: Problems and Promise Author(S): Steve Chan Reviewed Work(S): Source: Mershon International Studies Review, Vol

In Search of Democratic Peace: Problems and Promise Author(s): Steve Chan Reviewed work(s): Source: Mershon International Studies Review, Vol. 41, No. 1 (May, 1997), pp. 59-91 Published by: Blackwell Publishing on behalf of The International Studies Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/222803 . Accessed: 03/01/2012 11:13 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Blackwell Publishing and The International Studies Association are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Mershon International Studies Review. http://www.jstor.org Mershon International Studies Review (1997) 41, 59-91 In Search of Democratic Peace: Problems and Promise STEVE CHAN Department of Political Science, University of Colorado This essay reviews the growing literature on the democratic peace. It assesses the evidence on whether democracies are more peaceful and, if so, in what ways. This assessment considers the match and mismatch among the data, methods, and theories generally used in exploring these questions. The review also examines the empirical support for several explanations of the democratic peace phenomenon. It concludes with some observations and suggestions for future research. Are democracies more peaceful in their foreign relations? If so, what are the theoretical explanations and policy implications of this phenomenon? These ques- tions have been the focus of much recent international relations research. -

Must War Find a Way?167

Richard K. Betts A Review Essay Stephen Van Evera, Causes of War: Power and the Roots of Conict Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1999 War is like love, it always nds a way. —Bertolt Brecht, Mother Courage tephen Van Evera’s book revises half of a fteen-year-old dissertation that must be among the most cited in history. This volume is a major entry in academic security studies, and for some time it will stand beside only a few other modern works on causes of war that aspiring international relations theorists are expected to digest. Given that political science syllabi seldom assign works more than a generation old, it is even possible that for a while this book may edge ahead of the more general modern classics on the subject such as E.H. Carr’s masterful polemic, 1 The Twenty Years’ Crisis, and Kenneth Waltz’s Man, the State, and War. Richard K. Betts is Leo A. Shifrin Professor of War and Peace Studies at Columbia University, Director of National Security Studies at the Council on Foreign Relations, and editor of Conict after the Cold War: Arguments on Causes of War and Peace (New York: Longman, 1994). For comments on a previous draft the author thanks Stephen Biddle, Robert Jervis, and Jack Snyder. 1. E.H. Carr, The Twenty Years’ Crisis, 2d ed. (New York: Macmillan, 1946); and Kenneth N. Waltz, Man, the State, and War (New York: Columbia University Press, 1959). See also Waltz’s more general work, Theory of International Politics (Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley, 1979); and Hans J. -

Reviewer Fatigue? Why Scholars PS Decline to Review Their Peers’ Work

AMERICAN POLITICAL SCIENCE ASSOCIATION Reviewer Fatigue? Why Scholars PS Decline to Review Their Peers’ Work | Marijke Breuning, Jeremy Backstrom, Jeremy Brannon, Benjamin Isaak Gross, Announcing Science & Politics Political Michael Widmeier Why, and How, to Bridge the “Gap” Before Tenure: Peer-Reviewed Research May Not Be the Only Strategic Move as a Graduate Student or Young Scholar Mariano E. Bertucci Partisan Politics and Congressional Election Prospects: Political Science & Politics Evidence from the Iowa Electronic Markets Depression PSOCTOBER 2015, VOLUME 48, NUMBER 4 Joyce E. Berg, Christopher E. Peneny, and Thomas A. Rietz dep1 dep2 dep3 dep4 dep5 dep6 H1 H2 H3 H4 H5 H6 Bayesian Analysis Trace Histogram −.002 500 −.004 400 −.006 300 −.008 200 100 −.01 0 2000 4000 6000 8000 10000 0 Iteration number −.01 −.008 −.006 −.004 −.002 Autocorrelation Density 0.80 500 all 0.60 1−half 400 2−half 0.40 300 0.20 200 0.00 100 0 10 20 30 40 0 Lag −.01 −.008 −.006 −.004 −.002 Here are some of the new features: » Bayesian analysis » IRT (item response theory) » Multilevel models for survey data » Panel-data survival models » Markov-switching models » SEM: survey data, Satorra–Bentler, survival models » Regression models for fractional data » Censored Poisson regression » Endogenous treatment effects » Unicode stata.com/psp-14 Stata is a registered trademark of StataCorp LP, 4905 Lakeway Drive, College Station, TX 77845, USA. OCTOBER 2015 Cambridge Journals Online For further information about this journal please go to the journal website at: journals.cambridge.org/psc APSA Task Force Reports AMERICAN POLITICAL SCIENCE ASSOCIATION Let’s Be Heard! How to Better Communicate Political Science’s Public Value The APSA task force reports seek John H. -

Was the Cold War a Security Dilemma?

Was the Cold War a Security Dilemma? Robert Jervis xploring whether the Cold War was a security dilemma illumi- nates botEh history and theoretical concepts. The core argument of the security dilemma is that, in the absence of a supranational authority that can enforce binding agreements, many of the steps pursued by states to bolster their secu- rity have the effect—often unintended and unforeseen—of making other states less secure. The anarchic nature of the international system imposes constraints on states’ behavior. Even if they can be certain that the current in- tentions of other states are benign, they can neither neglect the possibility that the others will become aggressive in the future nor credibly guarantee that they themselves will remain peaceful. But as each state seeks to be able to pro- tect itself, it is likely to gain the ability to menace others. When confronted by this seeming threat, other states will react by acquiring arms and alliances of their own and will come to see the rst state as hostile. In this way, the inter- action between states generates strife rather than merely revealing or accentuat- ing con icts stemming from differences over goals. Although other motives such as greed, glory, and honor come into play, much of international politics is ultimately driven by fear. When the security dilemma is at work, interna- tional politics can be seen as tragic in the sense that states may desire—or at least be willing to settle for—mutual security, but their own behavior puts this very goal further from their reach.1 1. -

The Organizational Process and Bureaucratic Politics Paradigms: Retrospect and Prospect Author(S): David A

The Organizational Process and Bureaucratic Politics Paradigms: Retrospect and Prospect Author(s): David A. Welch Source: International Security , Fall, 1992, Vol. 17, No. 2 (Fall, 1992), pp. 112-146 Published by: The MIT Press Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2539170 REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2539170?seq=1&cid=pdf- reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms The MIT Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to International Security This content downloaded from 209.6.197.28 on Wed, 07 Oct 2020 15:39:26 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms The Organizational David A. Welch Process and Bureaucratic Politics Paradigms Retrospect and Prospect 1991 marked the twentieth anniversary of the publication of Graham Allison's Essence of De- cision: Explaining the Cuban Missile Crisis. ' The influence of this work has been felt far beyond the study of international politics. Since 1971, it has been cited in over 1,100 articles in journals listed in the Social Sciences Citation Index, in every periodical touching political science, and in others as diverse as The American Journal of Agricultural Economics and The Journal of Nursing Adminis- tration. -

Theory of International Politics

Theory of International Politics KENNETH N. WALTZ University of Califo rnia, Berkeley .A yy Addison-Wesley Publishing Company Reading, Massachusetts Menlo Park, California London • Amsterdam Don Mills, Ontario • Sydney Preface This book is in the Addison-Wesley Series in Political Science Theory is fundamental to science, and theories are rooted in ideas. The National Science Foundation was willing to bet on an idea before it could be well explained. The following pages, I hope, justify the Foundation's judgment. Other institu tions helped me along the endless road to theory. In recent years the Institute of International Studies and the Committee on Research at the University of Califor nia, Berkeley, helped finance my work, as the Center for International Affairs at Harvard did earlier. Fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation and from the Institute for the Study of World Politics enabled me to complete a draft of the manuscript and also to relate problems of international-political theory to wider issues in the philosophy of science. For the latter purpose, the philosophy depart ment of the London School of Economics provided an exciting and friendly envi ronment. Robert Jervis and John Ruggie read my next-to-last draft with care and in sight that would amaze anyone unacquainted with their critical talents. Robert Art and Glenn Snyder also made telling comments. John Cavanagh collected quantities of preliminary data; Stephen Peterson constructed the TabJes found in the Appendix; Harry Hanson compiled the bibliography, and Nacline Zelinski expertly coped with an unrelenting flow of tapes. Through many discussions, mainly with my wife and with graduate students at Brandeis and Berkeley, a number of the points I make were developed. -

Two Cheers for Bargaining Theory Two Cheers for David A

Two Cheers for Bargaining Theory Two Cheers for David A. Lake Bargaining Theory Assessing Rationalist Explanations of the Iraq War The Iraq War has been one of the most signiªcant events in world politics since the end of the Cold War. One of the ªrst preventive wars in history, it cost trillions of dollars, re- sulted in more than 4,500 U.S. and coalition casualties (to date), caused enor- mous suffering in Iraq, and may have spurred greater anti-Americanism in the Middle East even while reducing potential threats to the United States and its allies. Yet, despite its profound importance, the causes of the war have re- ceived little sustained analysis from scholars of international relations.1 Al- though there have been many descriptions of the lead-up to the war, the ªghting, and the occupation, these largely journalistic accounts explain how but not why the war occurred.2 In this article, I assess a leading academic theory of conºict—the rationalist approach to war or, simply, bargaining theory—as one possible explanation of the Iraq War.3 Bargaining theory is currently the dominant approach in conºict David A. Lake is Jerri-Ann and Gary E. Jacobs Professor of Social Sciences, Distinguished Professor of Political Science, and Associate Dean of Social Sciences at the University of California, San Diego. He is the author, most recently, of Hierarchy in International Relations (Cornell University Press, 2009). The author is indebted to Peter Gourevitch, Stephan Haggard, Miles Kahler, James Long, Rose McDermott, Etel Solingen, and Barbara Walter for helpful discussions on Iraq or comments on this article. -

STILL LOOKING for AUDIENCE COSTS Erik Gartzke and Yonatan

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Essex Research Repository STILL LOOKING FOR AUDIENCE COSTS Erik Gartzke and Yonatan Lupu Eighteen years after publication of James Fearon’s article stressing the importance of domestic audience costs in international crisis bargaining, we continue to look for clear evidence to support or falsify his argument. 1 Notwithstanding the absence of a compelling empirical case for or against audience costs, much of the discipline has grown fond of Fearon’s basic framework. A key reason for the importance of Fearon’s claims has been the volume of theories that build on the hypothesis that leaders subject to popular rule are better able to generate audience costs. Scholars have relied on this logic, for example, to argue that democracies are more likely to win the wars they fight, 2 that democracies are more reliable allies, 3 and as an explanation for the democratic peace. 4 A pair of recent studies, motivated largely by limitations in the research designs of previous projects, offers evidence the authors interpret as contradicting audience cost theory. 5 Although we share the authors’ ambivalence about audience costs, we are not convinced by their evidence. What one seeks in looking for audience costs is evidence of a causal mechanism, not just of a causal effect. Historical case studies can be better suited to detecting causal mechanisms Erik Gartzke is an associate professor in the Department of Political Science, University of California, San Diego.Yonatan Lupu is a Postdoctoral Research Associate at Princeton University. -

When Are Arms Races Dangerous? When Are Arms Races Charles L

When Are Arms Races Dangerous? When Are Arms Races Charles L. Glaser Dangerous? Rational versus Suboptimal Arming Are arms races dan- gerous? This basic international relations question has received extensive at- tention.1 A large quantitative empirical literature addresses the consequences of arms races by focusing on whether they correlate with war, but remains divided on the answer.2 The theoretical literature falls into opposing camps: (1) arms races are driven by the security dilemma, are explained by the rational spiral model, and decrease security, or (2) arms races are driven by revisionist adversaries, explained by the deterrence model, and increase security.3 These Charles L. Glaser is a Professor in the Irving B. Harris Graduate School of Public Policy Studies at the Uni- versity of Chicago. For their helpful comments on earlier drafts of this article, the author would like to thank James Fearon, Michael Freeman, Lloyd Gruber, Chaim Kaufmann, John Schuessler, Stephen Walt, the anonymous reviewers for International Security, and participants in seminars at the Program on In- ternational Security Policy at the University of Chicago, the Program on International Political Economy and Security at the University of Chicago, the John M. Olin Institute at Harvard Univer- sity, and the Institute of War and Peace Studies at Columbia. He also thanks John Schuessler for valuable research assistance. 1. The pioneering study is Samuel P. Huntington, “Arms Races: Prerequisites and Results,” Public Policy, Vol. 8 (1958), pp. 41–86. Historical treatments include Paul Kennedy, “Arms-Races and the Causes of War, 1850–1945,” in Kennedy, Strategy and Diplomacy, 1870–1945 (London: George Allen and Unwin, 1983); and Grant T. -

Theories of War and Peace

1 THEORIES OF WAR AND PEACE POLI SCI 631 Rutgers University Fall 2018 Jack S. Levy [email protected] http://fas-polisci.rutgers.edu/levy/ Office Hours: Hickman Hall #304, Tuesday after class and by appointment "War is a matter of vital importance to the State; the province of life or death; the road to survival or ruin. It is mandatory that it be thoroughly studied." Sun Tzu, The Art of War In this seminar we undertake a comprehensive review of the theoretical and empirical literature on interstate war, focusing primarily on the causes of war and the conditions of peace but giving some attention to the conduct and termination of war. We emphasize research in political science but include some coverage of work in other disciplines. We examine the leading theories, their key causal variables, the paths or mechanisms through which those variables lead to war or to peace, and the degree of empirical support for various theories. Our survey includes research utilizing a variety of methodological approaches: qualitative, quantitative, experimental, formal, and experimental. Our primary focus, however, is on the logical coherence and analytic limitations of the theories and the kinds of research designs that might be useful in testing them. The seminar is designed primarily for graduate students who want to understand – and ultimately contribute to – the theoretical and empirical literature in political science on war, peace, and security. Students with different interests and students from other departments can also benefit from the seminar and are also welcome. Ideally, members of the seminar will have some familiarity with basic issues in international relations theory, philosophy of science, research design, and statistical methods.