Egypt's Judiciary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newton Spence and Peter Hughes V the Queen

SAINT VINCENT & THE GRENADINES IN THE COURT OF APPEAL CRIMINAL APPEAL NO. 20 OF 1998 BETWEEN: NEWTON SPENCE Appellant and THE QUEEN Respondent and SAINT LUCIA IN THE COURT OF APPEAL CRIMINAL APPEAL NO. 14 OF 1997 BETWEEN: PETER HUGHES Appellant and THE QUEEN Respondent Before: The Hon. Sir Dennis Byron Chief Justice The Hon. Mr. Albert Redhead Justice of Appeal The Hon. Mr. Adrian Saunders Justice of Appeal (Ag.) Appearances: Mr. J. Guthrie QC, Mr. K. Starmer and Ms. N. Sylvester for the Appellant Spence Mr. E. Fitzgerald QC and Mr. M. Foster for the Appellant Hughes Mr. A. Astaphan SC, Ms. L. Blenman, Solicitor General, Mr. James Dingemans, Mr. P. Thompson, Mr. D. Browne, Solicitor General, Dr. H. Browne and Ms. S. Bollers for the Respondents -------------------------------------------- 2000: December 7, 8; 2001: April 2. -------------------------------------------- JUDGMENT [1] BYRON, C.J.: This is a consolidated appeal, which concerns two appellants convicted of murder and sentenced to death in Saint Vincent and Saint Lucia respectively who exhausted their appeals against conviction and raised constitutional arguments against the mandatory sentence of death before the Privy Council which had not previously been raised in the Eastern Caribbean Court of Appeal. Background [2] The Privy Council granted leave to both appellants to appeal against sentence and remitted the matter to the Eastern Caribbean Court of Appeal to consider and determine whether (a) the mandatory sentence of death imposed should be quashed (and if so what sentence (including the sentence of death) should be imposed), or (b) the mandatory sentence of death imposed ought to be affirmed. -

When the Dust Settles

WHEN THE DUST SETTLES Judicial Responses to Terrorism in the Sahel By Junko Nozawa and Melissa Lefas October 2018 Copyright © 2018 Global Center on Cooperative Security All rights reserved. For permission requests, write to the publisher at: 1101 14th Street NW, Suite 900 Washington, DC 20005 USA DESIGN: Studio You London CONTRIBUTING AUTHORS: Heleine Fouda, Gildas Barbier, Hassane Djibo, Wafi Ougadeye, and El Hadji Malick Sow SUGGESTED CITATION: Junko Nozawa and Melissa Lefas, “When the Dust Settles: Judicial Responses to Terrorism in the Sahel,” Global Center on Cooperative Security, October 2018. globalcenter.org @GlobalCtr WHEN THE DUST SETTLES Judicial Responses to Terrorism in the Sahel By Junko Nozawa and Melissa Lefas October 2018 ABOUT THE AUTHORS JUNKO NOZAWA JUNKO NOZAWA is a Legal Analyst for the Global Center on Cooperative Security, where she supports programming in criminal justice and rule of law, focusing on human rights and judicial responses to terrorism. In the field of international law, she has contrib- uted to the work of the International Criminal Court, regional human rights courts, and nongovernmental organizations. She holds a JD and LLM from Washington University in St. Louis. MELISSA LEFAS MELISSA LEFAS is Director of Criminal Justice and Rule of Law Programs for the Global Center, where she is responsible for overseeing programming and strategic direction for that portfolio. She has spent the previous several years managing Global Center programs throughout East Africa, the Middle East, North Africa, the Sahel, and South Asia with a primary focus on human rights, capacity development, and due process in handling terrorism and related cases. -

Abuses by the Supreme State Security Prosecution

PERMANENT STATE OF EXCEPTION ABUSES BY THE SUPREME STATE SECURITY PROSECUTION Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2019 Cover photo: Illustration depicting, based on testimonies provided to Amnesty International, the inside Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons of an office of a prosecutor at the Supreme State Security Prosecution. (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. © Inkyfada https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2019 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: MDE 12/1399/2019 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS GLOSSARY 5 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 7 METHODOLOGY 11 BACKGROUND 13 SUPREME STATE SECURITY PROSECUTION 16 JURISDICTION 16 HISTORY 17 VIOLATIONS OF FAIR TRIAL GUARANTEES 20 ARBITRARY DETENTION -

Advisory Service on International Humanitarian Law

ADVISORY SERVICE ON INTERNATIONAL HUMANITARIAN LAW NATIONAL COMMITTEES AND SIMILAR BODIES ON INTERNATIONAL HUMANITARIAN LAW (25 January 2021) NATIONAL COMMITTEES AND SIMILAR BODIES ON INTERNATIONAL HUMANITARIAN LAW As of 25 January 2021 (total by region) EUROPE CENTRAL ASIA ASIA & PACIFIC THE AMERICAS AFRICA MIDDLE EAST Austria Kazakhstan Australia Argentina Algeria Bahrain Belarus Kyrgyzstan Bangladesh Bolivia Benin Egypt Belgium Tajikistan China (People’s Republic of) Brazil Botswana Iran (Islamic Republic of) Bulgaria Turkmenistan Cook Islands Canada Burkina Faso Iraq Croatia Indonesia Chile Cabo Verde Jordan Cyprus Japan Colombia Comoros Kuwait Czech Republic Kiribati Costa Rica Côte d'Ivoire Lebanon Denmark Malaysia Dominican Republic Eswatini Oman Finland Mongolia1* El Salvador Gambia Palestine France Nepal Ecuador Guinea-Bissau Qatar Georgia New Zealand Guatemala Kenya Saudi Arabia Germany Papua New Guinea Honduras Lesotho Syrian Arab Republic Greece Philippines Mexico Liberia United Arab Emirates Hungary Republic of Korea (the) Nicaragua Libya Yemen Iceland Samoa Panama Madagascar Ireland Sri Lanka Paraguay Malawi Italy (two committees) Vanuatu Peru Mauritius Lithuania Trinidad & Tobago Morocco Netherlands Uruguay Namibia Republic of North Macedonia Venezuela Niger Poland (two committees) Nigeria Republic of Moldova Senegal Romania Seychelles Slovakia Sierra Leone Slovenia South Africa Spain Sudan Sweden (two committees) Togo Switzerland Tunisia Ukraine Uganda United Kingdom Zambia Zimbabwe TOTAL: 30 TOTAL: 4 TOTAL: 17 TOTAL: -

France 2014 Human Rights Report

FRANCE 2014 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY France is a multi-party constitutional democracy. The president of the republic is elected by popular vote for a five-year term. Voters elected Francois Hollande to that position in 2012. The upper house (Senate) of the bicameral parliament is elected indirectly through an electoral college, while the public elects the lower house (National Assembly) directly. The 2012 presidential and National Assembly elections and the 2014 elections for the Senate were considered free and fair. Authorities generally maintained effective control over the security forces. The most significant human rights problems during the year included an increasing number of anti-Semitic incidents. Anti-Semitic incidents and violence surged during the summer in connection with public protests against Israeli actions in Gaza. Government evictions of Roma from illegal camps, as well as overcrowded and unhygienic prisons, and problems in the judicial system, including lengthy pretrial detention and protracted investigations and trials, continued. Other reported human rights problems included instances of excessive use of force by police, societal violence against women, anti-Muslim incidents, and trafficking in persons. The government took steps to prosecute and punish security forces and other officials who committed abuses. Impunity was not widespread. Note: The country includes 11 overseas administrative divisions covered in this report. Four overseas territories in French Guiana, Guadeloupe, Martinique, and La Reunion have the same political status as the 22 metropolitan regions and 101 departments on the mainland. Five divisions are overseas “collectivities”: French Polynesia, Saint-Barthelemy, Saint-Martin, Saint-Pierre and Miquelon, and Wallis and Futuna. -

How to Navigate Egypt's Enduring Human Rights Crisis

How to Navigate Egypt’s Enduring Human Rights Crisis BLUEPRINT FOR U.S. GOVERNMENT POLICY January 2016 Human Rights First American ideals. Universal values. On human rights, the United States must be a beacon. Activists fighting for freedom around the globe continue to look to us for inspiration and count on us for support. Upholding human rights is not only a moral obligation; it’s a vital national interest. America is strongest when our policies and actions match our values. Human Rights First is an independent advocacy and action organization that challenges America to live up to its ideals. We believe American leadership is essential in the struggle for human rights so we press the U.S. government and private companies to respect human rights and the rule of law. When they don’t, we step in to demand reform, accountability and justice. Around the world, we work where we can best harness American influence to secure core freedoms. We know that it is not enough to expose and protest injustice, so we create the political environment and policy solutions necessary to ensure consistent respect for human rights. Whether we are protecting refugees, combating torture, or defending persecuted minorities, we focus not on making a point, but on making a difference. For over 30 years, we’ve built bipartisan coalitions and teamed up with frontline activists and lawyers to tackle issues that demand American leadership. Human Rights First is a nonprofit, nonpartisan international human rights organization based in New York and Washington D.C. To maintain our independence, we accept no government funding. -

Egypt Presidential Election Observation Report

EGYPT PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION OBSERVATION REPORT JULY 2014 This publication was produced by Democracy International, Inc., for the United States Agency for International Development through Cooperative Agreement No. 3263-A- 13-00002. Photographs in this report were taken by DI while conducting the mission. Democracy International, Inc. 7600 Wisconsin Avenue, Suite 1010 Bethesda, MD 20814 Tel: +1.301.961.1660 www.democracyinternational.com EGYPT PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION OBSERVATION REPORT July 2014 Disclaimer This publication is made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents are the responsibility of Democracy International, Inc. and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. CONTENTS CONTENTS ................................................................ 4 MAP OF EGYPT .......................................................... I ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ............................................. II DELEGATION MEMBERS ......................................... V ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ....................... X EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.............................................. 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................ 6 ABOUT DI .......................................................... 6 ABOUT THE MISSION ....................................... 7 METHODOLOGY .............................................. 8 BACKGROUND ........................................................ 10 TUMULT -

ACLED) - Revised 2Nd Edition Compiled by ACCORD, 11 January 2018

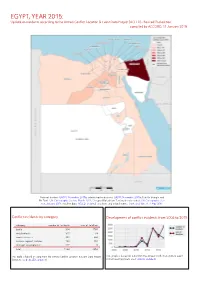

EGYPT, YEAR 2015: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) - Revised 2nd edition compiled by ACCORD, 11 January 2018 National borders: GADM, November 2015b; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015a; Hala’ib triangle and Bir Tawil: UN Cartographic Section, March 2012; Occupied Palestinian Territory border status: UN Cartographic Sec- tion, January 2004; incident data: ACLED, undated; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 Conflict incidents by category Development of conflict incidents from 2006 to 2015 category number of incidents sum of fatalities battle 314 1765 riots/protests 311 33 remote violence 309 644 violence against civilians 193 404 strategic developments 117 8 total 1244 2854 This table is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project This graph is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event (datasets used: ACLED, undated). Data Project (datasets used: ACLED, undated). EGYPT, YEAR 2015: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) - REVISED 2ND EDITION COMPILED BY ACCORD, 11 JANUARY 2018 LOCALIZATION OF CONFLICT INCIDENTS Note: The following list is an overview of the incident data included in the ACLED dataset. More details are available in the actual dataset (date, location data, event type, involved actors, information sources, etc.). In the following list, the names of event locations are taken from ACLED, while the administrative region names are taken from GADM data which serves as the basis for the map above. In Ad Daqahliyah, 18 incidents killing 4 people were reported. The following locations were affected: Al Mansurah, Bani Ebeid, Gamasa, Kom el Nour, Mit Salsil, Sursuq, Talkha. -

Is Perpetrated by Fundamentalist Sunnis, Except Terrorism Against Israel

All “Islamic Terrorism” Is Perpetrated by Fundamentalist Sunnis, Except Terrorism Against Israel By Eric Zuesse Region: Middle East & North Africa Global Research, June 10, 2017 Theme: Terrorism, US NATO War Agenda In-depth Report: IRAN: THE NEXT WAR?, IRAQ REPORT, SYRIA My examination of 54 prominent international examples of what U.S.President Donald Trump is presumably referring to when he uses his often-repeated but never defined phrase “radical Islamic terrorism” indicates that it is exclusively a phenomenon that is financed by the U.S. government’s Sunni fundamentalist royal Arab ‘allies’ and their subordinates, and not at all by Iran or its allies or any Shiites at all. Each of the perpetrators was either funded by those royals, or else inspired by the organizations, such as Al Qaeda and ISIS, that those royals fund, and which are often also armed by U.S.-made weapons that were funded by those royals. In other words: the U.S. government is allied with the perpetrators. Iran’s President Hassan Rouhani and Syrian counterpart Bashar al-Assad (Source: antiliberalnews.net) See the critique of this article by Kevin Barrett Stop the Smear Campaign (and Genocide) Against Sunni Islam!By Kevin Barrett, June 13, 2017 Though U.S. President Donald Trump blames Shias, such as the leaders of Iran and of Syria, for what he calls “radical Islamic terrorism,” and he favors sanctions etc. against them for that alleged reason, those Shia leaders and their countries are actually constantly being attacked by Islamic terrorists, and this terrorism is frequently perpetrated specifically in order to overthrow them (which the U.S. -

De-Securitizing Counterterrorism in the Sinai Peninsula

Policy Briefing April 2017 De-Securitizing Counterterrorism in the Sinai Peninsula Sahar F. Aziz De-Securitizing Counterrorism in the Sinai Peninsula Sahar F. Aziz The Brookings Institution is a private non-profit organization. Its mission is to conduct high-quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. The conclusions and recommendations of any Brookings publication are solely those of its author(s), and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Institution, its management, or its other scholars. Brookings recognizes that the value it provides to any supporter is in its absolute commitment to quality, independence and impact. Activities supported by its donors reflect this commitment and the analysis and recommendations are not determined by any donation. Copyright © 2017 Brookings Institution BROOKINGS INSTITUTION 1775 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20036 U.S.A. www.brookings.edu BROOKINGS DOHA CENTER Saha 43, Building 63, West Bay, Doha, Qatar www.brookings.edu/doha III De-Securitizing Counterterrorism in the Sinai Peninsula Sahar F. Aziz1 On October 22, 2016, a senior Egyptian army ideal location for lucrative human, drug, and officer was killed in broad daylight outside his weapons smuggling (much of which now home in a Cairo suburb.2 The former head of comes from Libya), and for militant groups to security forces in North Sinai was allegedly train and launch terrorist attacks against both murdered for demolishing homes and -

UN Assistance Mission for Iraq ﺑﻌﺜﺔ اﻷﻣﻢ اﻟﻤﺘﺤﺪة (UNAMI) ﻟﺘﻘﺪﻳﻢ اﻟﻤﺴﺎﻋﺪة

ﺑﻌﺜﺔ اﻷﻣﻢ اﻟﻤﺘﺤﺪة UN Assistance Mission for Iraq ﻟﺘﻘﺪﻳﻢ اﻟﻤﺴﺎﻋﺪة ﻟﻠﻌﺮاق (UNAMI) Human Rights Report 1 September– 31 October 2006 Summary 1. Despite the Government’s strong commitment to address growing human rights violations and lay the ground for institutional reform, violence reached alarming levels in many parts of the country affecting, particularly, the right to life and personal integrity. 2. The Iraqi Government, MNF-I and the international community must increase efforts to reassert the authority of the State and ensure respect for the rule of law by dismantling the growing influence of armed militias, by combating corruption and organized crime and by maintaining discipline within the security and armed forces. In this respect, it is encouraging that the Government, especially the Ministry of Human Rights, is engaged in the development of a national system based on the respect of human rights and the rule of law and is ready to address issues related to transitional justice so as to achieve national reconciliation and dialogue. 3. The preparation of the International Compact for Iraq, an agreement between the Government and the international community to achieve peace, stability and development based on the rule of law and respect for human rights, is perhaps a most significant development in the period. The objective of the Compact is to facilitate reconstruction and development while upholding human rights, the rule of law, and overcoming the legacy of the recent and distant past. 4. UNAMI Human Rights Office (HRO) received information about a large number of indiscriminate and targeted killings. Unidentified bodies continued to appear daily in Baghdad and other cities. -

A Death Foretold, P. 36

Pending Further Review One year of the church regularization committee A Death Foretold* An analysis of the targeted killing and forced displacement of Arish Coptic Christians First edition November 2018 Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights 14 al Saray al Korbra St., Garden City, Al Qahirah, Egypt. Telephone & fax: +(202) 27960197 - 27960158 www.eipr.org - [email protected] All printing and publication rights reserved. This report may be redistributed with attribution for non-profit pur- poses under Creative Commons license. www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0 *The title of this report is inspired by Colombian Nobel laureate Gabriel García Márquez’s novel Chronicle of a Death Foretold (1981) Acknowledgements This report was written by Ishak Ibrahim, researcher and freedom of religion and belief officer, and Sherif Mohey El Din, researcher in Criminal Justice Unit at EIPR. Ahmed Mahrous, Monitoring and Documentation Officer, contributed to the annexes and to acquiring victim and eyewitness testimonials. Amr Abdel Rahman, head of the Civil Liberties unit, edited the report. Ahmed El Sheibini did the copyediting. TABLE OF CONTENTS: GENERAL BACKGROUND OF SECTARIAN ATTACKS ..................................................................... 8 BACKGROUND ON THE LEGAL AND SOCIAL CONTEXT OF NORTH SINAI AND ITS PARTICULARS ............................................................................................................................................. 12 THE LEGAL SITUATION GOVERNING NORTH SINAI: FROM MILITARY COMMANDER DECREES