Newton Spence and Peter Hughes V the Queen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IN the CARIBBEAN COURT of JUSTICE Appellate Jurisdiction on APPEAL from the COURT of APPEAL of BELIZE CCJ

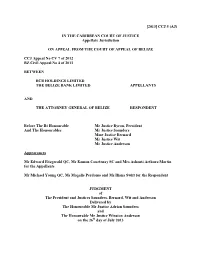

[2013] CCJ 5 (AJ) IN THE CARIBBEAN COURT OF JUSTICE Appellate Jurisdiction ON APPEAL FROM THE COURT OF APPEAL OF BELIZE CCJ Appeal No CV 7 of 2012 BZ Civil Appeal No 4 of 2011 BETWEEN BCB HOLDINGS LIMITED THE BELIZE BANK LIMITED APPELLANTS AND THE ATTORNEY GENERAL OF BELIZE RESPONDENT Before The Rt Honourable Mr Justice Byron, President And The Honourables Mr Justice Saunders Mme Justice Bernard Mr Justice Wit Mr Justice Anderson Appearances Mr Edward Fitzgerald QC, Mr Eamon Courtenay SC and Mrs Ashanti Arthurs-Martin for the Appellants Mr Michael Young QC, Ms Magalie Perdomo and Ms Iliana Swift for the Respondent JUDGMENT of The President and Justices Saunders, Bernard, Wit and Anderson Delivered by The Honourable Mr Justice Adrian Saunders and The Honourable Mr Justice Winston Anderson on the 26th day of July 2013 JUDGMENT OF THE HONOURABLE MR JUSTICE SAUNDERS [1] The London Court of International Arbitration (“the Tribunal”) determined that the State of Belize should pay damages for dishonouring certain promises it had made to two commercial companies, namely, BCB Holdings Limited and The Belize Bank Limited (“the Companies”). The promises were contained in a Settlement Deed as Amended (“the Deed”) executed in March 2005. The Deed provided that the Companies should enjoy, from the 1st day of April, 2005, a tax regime specially crafted for them and at variance with the tax laws of Belize. [2] This unique regime was never legislated but it was honoured by the State for two years until it was repudiated in 2008 after a change of administration in Belize following a General Election. -

Tribute to the Late Dr Joseph Samuel Nathaniel Archibald, QC the Right Honourable Sir Dennis Byron, President of the Caribbean Court of Justice

Tribute to the Late Dr Joseph Samuel Nathaniel Archibald, QC The Right Honourable Sir Dennis Byron, President of the Caribbean Court of Justice Funeral Service of the Late Dr Joseph Samuel Nathaniel Archibald Tortola, British Virgin Islands 26 April 2014 Dr. Joseph Samuel Archibald, QC was a Saint Kittitian-born British Virgin Islander jurist,lawyer, registrar, magistrate, former Director of Public Prosecutions, and former Attorney General. Archibald was one of the first presidents of the BVI Bar Association, a position he held from 1986 until 1994. He also served as a founder and founding president of the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS) Bar Association from 1991 until 1996. As president of the OECS Bar Association, Archibald oversaw the ethical standards and rules under which new solicitors and barristers must adhere to to practice before the Eastern Caribbean Supreme Court. Joseph Archibald was reappointed to a second term on the CARICOM Regional Judicial and Legal Services Commission in 2010. Remarks By The Right Honourable Sir Dennis Byron, President of the Caribbean Court of Justice, on the occasion of The Funeral of the Late Dr Joseph Samuel Nathaniel Archibald 26 April 2014 On the 3rd day of April, 2014, Dr. Joseph Samuel Nathaniel Archibald, Q.C., without the preparation by any prolonged illness, peacefully passed away at his home at the young age of 80. Up to the end he had retained his youthful vigour, enthusiasm and interests with inexhaustible energy. He was born at Cayon Street in Basseterre on January 27th, 1934, to Mr. William and Mrs. Mildred Archibald. His parents were known for their geniality, industry and intelligence, traits that they passed on to their children. -

When the Dust Settles

WHEN THE DUST SETTLES Judicial Responses to Terrorism in the Sahel By Junko Nozawa and Melissa Lefas October 2018 Copyright © 2018 Global Center on Cooperative Security All rights reserved. For permission requests, write to the publisher at: 1101 14th Street NW, Suite 900 Washington, DC 20005 USA DESIGN: Studio You London CONTRIBUTING AUTHORS: Heleine Fouda, Gildas Barbier, Hassane Djibo, Wafi Ougadeye, and El Hadji Malick Sow SUGGESTED CITATION: Junko Nozawa and Melissa Lefas, “When the Dust Settles: Judicial Responses to Terrorism in the Sahel,” Global Center on Cooperative Security, October 2018. globalcenter.org @GlobalCtr WHEN THE DUST SETTLES Judicial Responses to Terrorism in the Sahel By Junko Nozawa and Melissa Lefas October 2018 ABOUT THE AUTHORS JUNKO NOZAWA JUNKO NOZAWA is a Legal Analyst for the Global Center on Cooperative Security, where she supports programming in criminal justice and rule of law, focusing on human rights and judicial responses to terrorism. In the field of international law, she has contrib- uted to the work of the International Criminal Court, regional human rights courts, and nongovernmental organizations. She holds a JD and LLM from Washington University in St. Louis. MELISSA LEFAS MELISSA LEFAS is Director of Criminal Justice and Rule of Law Programs for the Global Center, where she is responsible for overseeing programming and strategic direction for that portfolio. She has spent the previous several years managing Global Center programs throughout East Africa, the Middle East, North Africa, the Sahel, and South Asia with a primary focus on human rights, capacity development, and due process in handling terrorism and related cases. -

Address by the Chief Justice of the Eastern Caribbean Supreme Court the Hon. Mr. Justice Hugh Rawlins to Mark the Opening of T

ADDRESS BY THE CHIEF JUSTICE OF THE EASTERN CARIBBEAN SUPREME COURT THE HON. MR. JUSTICE HUGH RAWLINS TO MARK THE OPENING OF THE LAW YEAR 2008/2009 CASTRIES SAINT LUCIA MONDAY, 15th SEPTEMBER 2008 PRODUCED BY THE COURT OF APPEAL OFFICE CASTRIES, SAINT LUCIA Introduction . Your Excellency, Dame Pearlette Louisy, Governor-General of Saint Lucia and Their Excellencies, the Heads of State of each of the OECS Member States and Territories;; . Honourable Heads of Government of each of the OECS Member States and Territories; . The Hon. Attorney-General & Minister of Justice, Senator Dr. Nicholas Frederick, and Hon. Attorneys-General and Ministers of Justice of each of the OECS Member States and Territories; . Honourable Ministers of Government of Saint Lucia and of each of the OECS Member States and Territories; . Honourable Judges of the Court of Appeal, Judges of the High Court and Masters ; . Honourable Leaders of the Opposition of the OECS Member States and Territories; . The Honourable Speakers of the Houses of Representatives, Presidents of the Senates and Members of Parliament of each of the OECS Member States and Territories; . Chief/Senior Magistrates and Magistrates of the OECS; . The Chief Registrar, Deputy Chief Registrar and Registrars of the Eastern Caribbean Supreme Court; . The President of the OECS Bar Association and Presidents of constituent Bar Associations; 2 . Learned members of the Inner Bar of each of the OECS Member States and Territories; . Members of the Utter Bar, learned in the Law, of each of the OECS Member States and Territories; . Commissioners of Police, Police Officers and Heads of Correctional Facilities of St. -

Paying Homage to the Right Honourable Sir C.M. Dennis Byron Meet the Team Chief Editor CAJO Executive Members the Honourable Mr

NewsJuly 2018 Issue 8 Click here to listen to the theme song of Black Orpheus as arranged by Mr. Neville Jules and played by the Massy Trinidad All Stars Steel Orchestra. Paying Homage to The Right Honourable Sir C.M. Dennis Byron Meet the Team Chief Editor CAJO Executive Members The Honourable Mr. Justice Adrian Saunders Chairman Contributors Mr. Terence V. Byron, C.M.G. The Honourable Justice Mr. Adrian Saunders Madam Justice Indra Hariprashad-Charles Caribbean Court of Justice Retired Justice of Appeal Mr. Albert Redhead Mr. Justice Constant K. Hometowu Vice Chairman Mr. Justice Vagn Joensen Justice of Appeal Mr. Peter Jamadar Trinidad and Tobago Graphic Artwork & Layout Ms. Danielle M Conney Sir Marston Gibson, Chief Justice - Barbados Country Representativesc Chancellor Yonnette Cummings-Edwards - Guyana Mr. Justice Mauritz de Kort, Vice President of the Joint Justice Ian Winder - The Bahamas Court of The Dutch Antilles Registrar Shade Subair Williams - Bermuda; Madam Justice Sandra Nanhoe - Suriname Mrs. Suzanne Bothwell, Court Administrator – Cayman Madam Justice Nicole Simmons - Jamaica Islands Madam Justice Sonya Young – Belize Madam Justice Avason Quinlan-Williams - Trinidad and Tobago c/o Caribbean Court of Justice Master Agnes Actie - ECSC 134The CaribbeanHenry Street, Association of Judicial Of�icers (CAJO) Port of Spain, Chief Magistrate Christopher Birch – Barbados Trinidad & Tobago Senior Magistrate Patricia Arana - Belize Registrar Musa Ali - Caribbean Competition Commit- 623-2225 ext 3234 tee - Suriname [email protected] In This Issue Editor’s Notes Pages 3 - 4 Excerpts of the Family Story Pages 5 - 7 The Different Sides of Sir Dennis Pages 8 - 9 My Tribute to the Rt. -

Cenac and Others (Appellants) V Schafer (Respondent) (Saint Lucia)

[2016] UKPC 25 Privy Council Appeal No 0044 of 2015 JUDGMENT Cenac and others (Appellants) v Schafer (Respondent) (Saint Lucia) From the Court of Appeal of the Eastern Caribbean Supreme Court (Saint Lucia) before Lord Clarke Lord Sumption Lord Carnwath Lord Hodge Sir Kim Lewison JUDGMENT GIVEN ON 2 August 2016 Heard on 19 July 2016 Appellants Respondent Seryozha Cenac Peter I Foster QC Leslie Prospere Renee T St Rose (Instructed by Campbell (Instructed by Charles Chambers) Russell Speechlys LLP) SIR KIM LEWISON: 1. Like many places in and around the Caribbean the law of Saint Lucia restricts the holding of land by aliens without a government licence. The principal issues on this appeal concern the legal effect of those restrictions on a transaction between US citizens. 2. In 1986 Mr and Mrs Cenac, who are both citizens of Saint Lucia, owned a parcel of land extending to about eight acres known as La Battery. It was registered in the Land Registry as Block 0031B, Parcel 20. By a deed of sale dated 29 August 1986 Mr and Mrs Cenac sold the land to Dr and Mrs Smith, who are US citizens. The deed recited that Dr and Mrs Smith were duly licenced to hold the land by virtue of a licence granted under the Aliens (Landholding Regulation) Act (No 10 of 1973). The licence had been granted by the Governor-General on 30 August 1985, and was made subject to the conditions in its Second Schedule which read: “THE PROPERTY is to be used for the purpose of building a residence and developing agriculture - the building to be completed within three years of the date of issue of this licence.” 3. -

Judicial Review and the Conseil D'etat George D

Boston College Law School Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School Boston College Law School Faculty Papers January 1966 DeGaulle's Republic and the Rule of Law: Judicial Review and the Conseil d'Etat George D. Brown Boston College Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/lsfp Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons Recommended Citation George D. Brown. "DeGaulle's Republic and the Rule of Law: Judicial Review and the Conseil d'Etat." Boston University Law Review 46, (1966): 462-492. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Boston College Law School Faculty Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. :DE GAULLE'S REPUBLIC AND THE RULE OF LAW: JUDICIAL REVIEW AND THE CONSEIL D'ETAT GEORGE D. BROWN* Americans tend to regard France as a somewhat despotic country where drivers' licenses are summarily revoked by roadside tribunals, political opponents are treated badly, and in general the rule of law is lightly regarded.' From time to time disgruntled Frenchmen come forward to reinforce this picture.2 Against such a background of illiber- alism, the lack of judicial review of legislation in France does not seem surprising. And it has become a commonplace to present the French hostility to judicial review as a polar example of attitudes toward this institution.3 Yet there are ample signs that this generalization needs to be reexamined. -

Annual Report 2000

Eastern Caribbean Supreme Court Report 2000-2003 Anguilla, Antigua and Barbuda, The British Virgin Islands, The Commonwealth of Dominica, Grenada, Montserrat, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines 1 Mission Statement “Delivery of justice independently by competent officers in a prompt, fair, efficient and effective manner”. 2 Contents Introduction by the Honourable Chief Justice 4 Eastern Caribbean Judicial System 6 Members of the Judiciary 8 Developments and Initiatives Department of Court Administration 14 Judicial Training 18 Mediation 22 Court of Appeal Registry 23 Law Reports 24 Court Buildings 25 The Reform Programme 26 Funding of the Judiciary 35 Court Productivity 38 ECSC Contact Information 53 3 Introduction The Honourable Sir Dennis Byron Chief Justice This is the second Report of the Eastern Caribbean Supreme Court. The first was published for the period 1st August 1999 to 31st July 2000. As part of ensuring that the Court provides an account for the work, which it performs, a report will be published annually in time for the opening of the new law year. The Years 2000-2003 saw several significant developments in the Court as we continued with our reforms. In addition to the several administrative and procedural reforms taking place, the Court introduced a very successful pilot project in Court Connected Mediation. Mediation is fully in place in the member state of Saint Lucia and plans are in progress to replicate the activity in the other member states of the Court. The persons entrusted to manage the Court system take this job very seriously and we are determined to see the reforms bring about the desired results of dealing with cases in a just and timely manner. -

The Seychelles Law Reports

THE SEYCHELLES LAW REPORTS DECISIONS OF THE SUPREME COURT, CONSTITUTIONAL COURT AND COURT OF APPEAL ________________ 2017 _________________ PART 2 (Pp i-vi, 269-552) Published by Authority of the Chief Justice i (2017) SLR EDITORIAL BOARD Chief Justice – ex officio Attorney-General – ex officio Mr Kieran Shah of Middle Temple, Barrister Mr Bernard Georges of Gray’s Inn, Barrister CITATION These reports are cited thus: (2017) SLR Printed by ii THE SEYCHELLES JUDICIARY THE COURT OF APPEAL Hon F MacGregor, President Hon S Domah Hon A Fernando Hon J Msoffe Hon M Twomey THE SUPREME COURT (AND CONSTITUTIONAL COURT) Hon M Twomey,Chief Justice Hon D Karunakaran Hon B Renaud Hon M Burhan Hon G Dodin Hon F Robinson Hon E De Silva Hon C McKee Hon D Akiiki-Kiiza Hon R Govinden Hon S Govinden Hon S Nunkoo Hon M Vidot Hon L Pillay Master E Carolus iii (2017) SLR iv CONTENTS Digest of Cases ................................................................................................ vii Cases Reported Amesbury v President of Seychelles & Constitutional Appointments Authority ........ 69 Benstrong v Lobban ............................................................................................... 317 Bonnelame v National Assembly of Seychelles ..................................................... 491 D’Acambra & Esparon v Esparon ........................................................................... 343 David & Ors v Public Utilities Corporation .............................................................. 439 Delorie v Government of Seychelles -

MOROCCO: Human Rights at a Crossroads

Human Rights Watch October 2004 Vol. 16, No. 6(E) MOROCCO: Human Rights at a Crossroads I. SUMMARY................................................................................................................................ 1 II. RECOMMENDATIONS...................................................................................................... 4 To the Government of Morocco ........................................................................................... 4 To the Equity and Reconciliation Commission ................................................................... 6 To the United Nations............................................................................................................. 7 To the U.S. Government.........................................................................................................8 To the European Union and its member states................................................................... 8 To the Arab League.................................................................................................................. 9 III. INTRODUCTION: ADDRESSING PAST ABUSES................................................... 9 The Equity and Reconciliation Commission......................................................................14 Limits of the New Commission ...........................................................................................16 2003 Report of the Advisory Council for Human Rights ................................................23 IV. HUMAN RIGHTS AFTER THE -

The Gender Equality Issue CAJO NEWS Team

NOVEMBER 2016 • ISSUE 6 The Gender Equality Issue CAJO NEWS Team CHIEF EDITOR CAJO BOARD MEMBERS The Hon. Mr. Justice Adrian Saunders Mr. Justice Adrian Saunders (Chairman) Justice Charmaine Pemberton (Deputy Chairman) Chief Justice Yonette Cummings Chief Justice Evert Jan van der Poel CONTRIBUTORS Justice Christopher Blackman Justice Charles-Etta Simmons Justice Francis Belle Chief Magistrate Ann Marie Smith Justice Sandra Nanhoe-Gangadin Senior Magistrate Patricia Arana Justice Nicole Simmons Justice Sonya Young Parish Judge Simone Wolfe-Reece Magistrate Lisa Ramsumair-Hinds Registrar Barbara Cooke-Alleyne GRAPHIC ARTWORK, LAYOUT Registrar Camille Darville-Gomez Ms. Seanna Annisette The Caribbean Association of Judicial Ocers (CAJO) c/o Caribbean Court of Justice 134 Henry Street Port of Spain Trinidad and Tobago Tel: (868) 623-2225 ext. 3234 Email: [email protected] IN EDITOR’s THIS Notes ISSUE P.3- P.4 CAJO PROFILE By the time some of you read this edition of CAJO NEWS the Referendum results in Grenada SCAJOue. would have been known. This is assuming of course that the Referendum does take place on The Hon. Mr Justice November 24th as scheduled at the time of writing. The vote had earlier been slated for 27th Rolston Nelson October. This exercise in Constitution re-making holds huge implications not just for the people of Grenada, Carriacou and Petit Martinique but for the entire CARICOM and English speaking Caribbean. In this edition CAJO NEWS lists the choices before the people of our sister isles. In this issue, CAJO NEWS publishes an interview we conducted with Hon Mr Justice Rolston Nelson, the longest serving judge of the Caribbean Court of Justice. -

Private Prosecutions in Mauritius: Clarifying Locus Standi and Making the Director of Public Prosecutions More Accountable

African Journal of Legal Studies 10 (2017) 1–34 brill.com/ajls Private Prosecutions in Mauritius: Clarifying Locus Standi and Making the Director of Public Prosecutions more Accountable Jamil Ddamulira Mujuzi University of the Western Cape, South Africa [email protected] Abstract Case law shows that private prosecutions have been part of Mauritian law at least since 1873. In Mauritius there are two types of private prosecutions: private prosecutions by individuals; and private prosecutions by statutory bodies. Neither the Mauritian consti- tution nor legislation provides for the right to institute a private prosecution. Because of the fact that Mauritian legislation is not detailed on the issue of locus standi to insti- tute private prosecutions and does not address the issue of whether or not the Director of Public Prosecutions has to give reasons when he takes over and discontinues a pri- vate prosecution, the Supreme Court has had to address these issues. The Mauritian Supreme Court has held, inter alia, that a private prosecution may only be instituted by an aggrieved party (even in lower courts where this is not a statutory requirement) and that the Director of Public Prosecutions may take over and discontinue a private prosecution without giving reasons for his decision. However, the Supreme Court does not define “an aggrieved party.” In this article the author takes issue with the Court’s findings in these cases and, relying on legislation from other African countries, recom- mends how the law could be amended to strengthen the private prosecutor’s position. Keywords private prosecutions – Mauritius – Locus Standi – Director of Public Prosecutions – aggrieved party – supreme court © koninklijke brill nv, leiden, ���7 | doi �0.��63/�7087384-��3400Downloaded�6 from Brill.com10/03/2021 04:36:42PM via free access 2 Mujuzi I Introduction Private prosecutions have been part of Mauritian law for a long period of time.1 In Mauritius there are two types of private prosecutions: private pros- ecutions by individuals; and private prosecutions by statutory bodies.