Journeying-With-Bonhoeffer-Chapter-Sampler.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Preliminary Investigation and Critique of the Ethics of Dietrich Bonhoeffer

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1968 A Preliminary Investigation and Critique of the Ethics of Dietrich Bonhoeffer David W. Clark Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Clark, David W., "A Preliminary Investigation and Critique of the Ethics of Dietrich Bonhoeffer" (1968). Master's Theses. 2118. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/2118 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1968 David W. Clark A PRELIMINARY INVESTIGATION AND CRITIQUE OF THE ETHICS OF DIETRICH BONHOEFFER by David W. Clark A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School, Loyola University, Ohicago, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for !he Degree of Master of Arts J~e 1968 PREFACE This paper is a preliminary investigation of the "Christian Ethics" of Dietrich Bonhoeffer in terms of its self-consistency and sufficiency for moral guidance. As Christian, Bonhoefferts ethic serves as a concrete instance of the ways in which reli gious dogmas are both regulative and formative of human behavioro Accordingly, this paper will study (a) the internal consistency of the revealed data and structural principles within Bonhoef ferts system, and (b) the significance of biblical directives for moral decisionso The question of Bonhoefferfs "success," then, presents a double problem. -

Dietrich Bonhoeffer Confessing Christ in Nazi Germany Table of Contents

Revisiting the Manhattan Declaration n The Minister’s Toolbox Spring 2011 Dietrich Bonhoeffer Confessing Christ in Nazi Germany Table of Contents FROM THE DEAN EDITORIAL TEAM A Tale of Two Declarations Dean Timothy George 2 HISTORY Director of External Relations Tal Prince (M.Div. ’01) A Spoke in the Wheel Confessing Christ in Nazi Germany Editor 4 Betsy Childs CULTURE Costly Grace and Christian Designer Witness Jesse Palmer 12 TheVeryIdea.com Revisiting the Manhattan Declaration Photography Sheri Herum Chase Kuhn MINISTRY Rebecca Long Caroline Summers The Minister’s Toolbox 16 Why Ministers Buy Books For details on the cover image, please see page 4. COMMUNITY Beeson was created using Adobe InDesign CS4, Adobe PhotoShop CS4, CorelDraw X4, Beeson Portrait Microsoft Word 2007, and Bitstream typefaces Paula Davis Modern 20 and AlineaSans.AlineaSerif. 20 ...at this critical moment in our life together, we Community News Revisiting the Manhattan Declaration find it important to stand together in a common struggle, to practice what I Beeson Alumni once called “an ecumenism of the trenches.” Beeson Divinity School Carolyn McKinstry Tells Her Story Samford University 800 Lakeshore Drive Dean Timothy George Birmingham, AL 35229 MINISTRY (205) 726-2991 www.beesondivinity.com Every Person a Pastor ©2011-2012 Beeson Divinity School 28 eeson is affiliated with the National Association of Evangelicals and is accredited by the Association of Theological Schools in the United States Band Canada. Samford University is an Equal Opportunity Institution that complies with applicable law prohibiting discrimination in its educational and employment ROW 1; A Tale of Two Declarations 2; A Spoke in the Wheel 4; policies and does not unlawfully discriminate on the Costly Grace and Christian Witness 12; ROW 2;The Minister’s Toolbox 16; basis of race, color, sex, age, disability, or national or ethnic origin. -

Thomas Lloyd's Bonhoeffer

Bryn Mawr Presbyterian Church presents Thomas Lloyd’s Bonhoeffer Sunday, March 17, 2019 4:00 p.m. Sanctuary Welcome Welcome to this afternoon’s performance of Thomas Lloyd’sBonhoeffer . On behalf of the choir, I thank you for attending and hope you will return for our upcoming events - Daryl Robinson’s organ recital on March 31 and our performance of Bach’s St. Mark Passion on April 19. These past ten weeks of rehearsals have been intense, challenging, ear-opening, and ultimately, inspiring. Living, as we have, with the remarkable story of Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s life, intertwined as it was with his fellow theologians and his beloved fiancée, Maria, has taken us on a journey that has profoundly touched each of us. How does one wrap one’s mind around the life of a peace-loving theologian who ultimately participates in a plot to murder Adolf Hitler? Bonhoeffer’s story has challenged us to ponder what is right and wrong, matters of living the faith in challenging times, and how to be courageous. I am deeply grateful to Tom Lloyd for having the courage to tackle the composition of Bonhoeffer. Tom has succeeded in getting inside Dietrich and Maria’s minds and hearts. You hear their struggles. You are moved by a love that ultimately was thwarted by Bonhoeffer’s death at the hands of the Nazi’s. For me personally, the setting of Bonhoeffer’s favorite biblical passage, the Beatitudes, is simply brilliant. Through masterful use of rhythm and bi-tonality, Tom depicts the challenge of living these words. -

Hitler's American Model

Hitler’s American Model The United States and the Making of Nazi Race Law James Q. Whitman Princeton University Press Princeton and Oxford 1 Introduction This jurisprudence would suit us perfectly, with a single exception. Over there they have in mind, practically speaking, only coloreds and half-coloreds, which includes mestizos and mulattoes; but the Jews, who are also of interest to us, are not reckoned among the coloreds. —Roland Freisler, June 5, 1934 On June 5, 1934, about a year and a half after Adolf Hitler became Chancellor of the Reich, the leading lawyers of Nazi Germany gathered at a meeting to plan what would become the Nuremberg Laws, the notorious anti-Jewish legislation of the Nazi race regime. The meeting was chaired by Franz Gürtner, the Reich Minister of Justice, and attended by officials who in the coming years would play central roles in the persecution of Germany’s Jews. Among those present was Bernhard Lösener, one of the principal draftsmen of the Nuremberg Laws; and the terrifying Roland Freisler, later President of the Nazi People’s Court and a man whose name has endured as a byword for twentieth-century judicial savagery. The meeting was an important one, and a stenographer was present to record a verbatim transcript, to be preserved by the ever-diligent Nazi bureaucracy as a record of a crucial moment in the creation of the new race regime. That transcript reveals the startling fact that is my point of departure in this study: the meeting involved detailed and lengthy discussions of the law of the United States. -

Beyond All Cost

BEYOND ALL COST A Play about Dietrich Bonhoeffer By Thomas J. Gardiner Performance Rights It is an infringement of the federal copyright law to copy or reproduce this script in any manner or to perform this play without royalty payment. All rights are controlled by Eldridge Publishing Co. Inc. Call the publisher for additional scripts and further licensing information. The author’s name must appear on all programs and advertising with the notice: “Produced by special arrangement with Eldridge Publishing Co. Inc.” PUBLISHED BY ELDRIDGE PUBLISHING 95church.com © 1977 & 1993 by Thomas J. Gardiner Download your complete script from Eldridge Publishing https://95church.com/beyond-all-cost Beyond All Cost - 2 - DEDICATION Grateful acknowledgement is hereby made to: Harper & Row, Macmillan Publishing Company, and Christian Kaiser Verlag for their permission to quote from the works of Dietrich Bonhoeffer and Eberhard Bethge. The Chorus of Prisoners is dramatized from Bonhoeffer's poem "Night Voices in Tegel," used by permission of SCM Press, London. My thanks to Edward Tolk for his translations from “Mein Kampf,” and to Union Theological Library for allowing me access to their special collections. STORY OF THE PLAY The play tells the true story of Dietrich Bonhoeffer, a pastor who led the resistance to Hitler in the German church. Narrated by Eberhard Bethge, his personal friend, companion and biographer, the play follows Bonhoeffer from his years as a seminary professor in northern Germany, through the turbulent challenges presented by Hitler’s efforts to seize and wield power in both the state and the church. Bonhoeffer is seen leading his students to organize an underground seminary, to distribute clandestine anti-Nazi literature, and eventually to declare open public defiance of Hitler’s authority. -

Unit 23, Session 2 Jesus Teaches About the Cost of Discipleship

Unit 23, Session 2 Jesus Teaches About the Cost of Discipleship Summary and Goal In this session, we will learn about how our commitment to discipleship needs to start on the inside: with a heart and a mind that clearly understand that Jesus requires total submission from us and that submission is costly. It is no light thing to commit our lives to Christ; it isn’t something we can do halfway. But if we understand the immeasurable worth of Jesus’ commitment toward His disciples, we will be motivated to submit ourselves fully to Him. Session Outline 1. Being Jesus’ disciple requires a clear commitment (Luke 9:57-62). 2. Being Jesus’ disciple requires a total commitment (Luke 14:25-27). 3. Being Jesus’ disciple requires a costly commitment (Luke 14:28-35). Background Passages: Luke 9:57-62; 14:25-35 Session in a Sentence 2 Jesus shared that discipleship involves a clear, total, and costly commitment to following Him. Christ Connection Jesus taught that being His disciple comes at a cost. To be His disciple requires a clear and total commitment and will involve sacrifice. When we commit our entire lives to Jesus as His disciples, we emulate the One who laid down His life on our behalf for our salvation. Missional Application Because Jesus sacrificed His life on our behalf to provide our salvation, we seek to commit our time, resources, and energy for the work of sharing Christ with others so they too might be saved. 66 Date of My Bible Study: ______________________ © 2020 LifeWay Christian Resources Group Time GROUP MEMBER CONTENT Introduction EXPLAIN: Use the paragraphs in the DDG (p. -

Dietrich Bonhoeffer Auf Dem Weg Zur Freiheit

Unverkäufliche Leseprobe Wolfgang Huber Dietrich Bonhoeffer Auf dem Weg zur Freiheit 2019. 336 S., mit 25 Abbildungen ISBN 978-3-406-73137-2 Weitere Informationen finden Sie hier: https://www.chbeck.de/26691743 © Verlag C.H.Beck oHG, München Wolfgang Huber DIETRICH BONHOEFFER AUF DEM WEG ZUR FREIHEIT Ein Porträt C.H.Beck Mit 25 Abbildungen © Verlag C.H.Beck oHG, München 2019 Satz: Fotosatz Amann, Memmingen Druck und Bindung: GGP Media, Pößneck Umschlaggestaltung: Kunst oder Reklame, München Umschlagabbildung: Dietrich Bonhoeffer 1933; Foto: Evangelische Zentralbildkammer Witten / Luther Verlag Bielefeld Gedruckt auf säurefreiem, alterungsbeständigem Papier (hergestellt aus chlorfrei gebleichtem Zellstoff) Printed in Germany ISBN 978 3 406 73137 2 www.chbeck.de Inhalt 1. Prolog: Wer war Dietrich Bonhoeffer? Denken und Leben 9 Sturm und Drang 10 Bekenntnis und Widerstand 18 Zuversicht ohne Ende 27 Modern und zugleich liberal 33 2. Bildungswege Die Familie als Bildungsort 39 Nietzsche und andere Schulmänner 41 Rom, die Kirche und die Theologie 44 Abschlüsse und Aufbrüche 52 3. Die Kirche als Vorzeichen vor der Klammer Individuelle Spiritualität oder Gemeinschaft 61 Die soziale Gestalt des Glaubens 67 Weltkirche und Wortkirche 76 Das Gerechte tun und auf Gottes Zeit warten 84 4. Billige oder teure Gnade Immer wieder Luther 87 Unendliche Leiter und guter Baum 89 Nachfolge und Widerstand 94 Beten und das Gerechte tun 105 5. Die Bibel im Leben und in der Theologie Von der Bergpredigt zu den Losungen 110 Die Bibel vergegenwärtigen 117 Historischer Jesus oder gegenwärtiger Christus 121 Zurück zu den Anfängen des Verstehens 126 6. Christlicher Pazifismus Kirche und Welt, Frieden und Widerstand 129 Friedfertige und Pazifisten 130 Freund oder Feind 133 Nur Gebote, die heute wahr sind 136 Gewaltfrei Frieden machen 142 Zwischen Militarismus und doktrinärem Pazifismus 150 Willkürliches und lebensnotwendiges Töten 152 Bonhoeffers Aktualität 154 7. -

Honoring and Perpetuating the Legacy of Dietrich Bonhoeffer

Honoring and Perpetuating the Legacy of Dietrich Bonhoeffer The 2014 Charles H. Hackley Distinguished Lecture in the Humanities May 8, 2014 It is a great privilege to stand before you tonight and deliver the 2014 Charles H. Hackley Distinguished Lecture in the Humanities, and to receive this prestigious award in his name. As a child growing-up in Muskegon in the 1950s and 1960s, the name of Charles Hackley was certainly a respected name, if not an icon from Muskegon’s past, after which were named: the hospital in which I was born, the park in which I played, a Manual Training School and Gymnasium, a community college, an athletic field (Hackley Stadium) in which I danced as the Muskegon High School Indian mascot, and an Art Gallery and public library that I frequently visited. Often in going from my home in Lakeside through Glenside and then to Muskegon Heights, we would drive on Hackley Avenue. I have deep feelings about that Hackley name as well as many good memories of this town, Muskegon, where my life journey began. It is really a pleasure to return to Muskegon and accept this honor, after living away in the state of Minnesota for forty-six years. I also want to say thank you to the Friends of the Hackley Public Library, their Board President, Carolyn Madden, and the Director of the Library, Marty Ferriby. This building, in which we gather tonight, St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, also holds a very significant place in the life of my family. My great-grandfather, George Alfred Matthews, came from Bristol, England in 1878, and after living in Newaygo and Fremont, settled here in Muskegon and was a very active deacon in this congregation until his death in 1921. -

Jesus Teaches About the Cost of Discipleship

Unit .23 Session .02 Jesus Teaches About the Cost of Discipleship Scripture Luke 9:57-62; 14:25-35 57 As they were going along the road, someone said and come after me cannot be my disciple. 28 For which to him, “I will follow you wherever you go.” 58 And of you, desiring to build a tower, does not first sit down Jesus said to him, “Foxes have holes, and birds of the air and count the cost, whether he has enough to complete have nests, but the Son of Man has nowhere to lay his it? 29 Otherwise, when he has laid a foundation and head.” 59 To another he said, “Follow me.” But he said, is not able to finish, all who see it begin to mock him, “Lord, let me first go and bury my father.” 60 And Jesus 30 saying, ‘This man began to build and was not able said to him, “Leave the dead to bury their own dead. to finish.’31 Or what king, going out to encounter But as for you, go and proclaim the kingdom of God.” another king in war, will not sit down first and deliberate 61 Yet another said, “I will follow you, Lord, but let me whether he is able with ten thousand to meet him who first say farewell to those at my home.”62 Jesus said comes against him with twenty thousand? 32 And if to him, “No one who puts his hand to the plow and not, while the other is yet a great way off, he sends a looks back is fit for the kingdom of God.” …25 Now delegation and asks for terms of peace. -

To Read the Full Text, Click Here

TEXT For Conduct And Innocents (drama in verse) by J. Chester Johnson Copyright © 2015 by J. Chester Johnson 1 Dietrich Bonhoeffer: Germany’s Jeremiah Born 1906 in Breslau, Germany (now, part of Poland) into a prominent, but not particularly religious family, Dietrich Bonhoeffer embraced the teachings of Protestantism early, becoming a well-known theologian and acclaimed writer while still in his twenties. When most of the Church leadership in Germany crumbled under the weight of Nazism, Bonhoeffer and a group of colleagues set about establishing the Confessing Church as a moral and spiritual counterforce. Bonhoeffer also plotted with a group of co-conspirators to overthrow Hitler; toward that end, he participated in organizing efforts to assassinate the Nazi leader. Arrested in April, 1943, Bonhoeffer remained in prison for the rest of his life. Remnants of the Hitler command were so obsessed with Bonhoeffer’s death that they executed him at the Flossenburg concentration camp, located near the Czechoslovakian border, on April 9, 1945, only two weeks before American liberation of the camp. Stripped of clothing, tortured and led naked to the gallows yard, he was then hanged from a tree. In 1930, Dietrich Bonhoeffer arrived here in New York City from Germany with a doctorate of theology and additional graduate work in hand and with some experience as a curate for a German-speaking congregation in Barcelona, Spain. He had been awarded a fellowship to Union Theological Seminary, where he came under the influence of many of the leading theological luminaries of the day, including Reinhold Niebuhr, a major force for social ethics. -

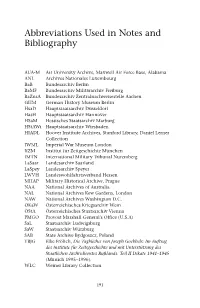

Abbreviations Used in Notes and Bibliography

Abbreviations Used in Notes and Bibliography AUA-M Air University Archive, Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama ANL Archives Nationales Luxembourg BaB Bundesarchiv Berlin BaMF Bundesarchiv Militärarchiv Freiburg BaZnsA Bundesarchiv Zentralnachweisestelle Aachen GHM German History Museum Berlin HsaD Hauptstaatsarchiv Düsseldorf HasH Hauptstaatsarchiv Hannover HSaM Hessisches Staatsarchiv Marburg HStAWi Hauptstaatsarchiv Wiesbaden HIADL Hoover Institute Archives, Stanford Library, Daniel Lerner Collection IWML Imperial War Museum London IfZM Institut für Zeitgeschichte München IMTN International Military Tribunal Nuremberg LaSaar Landesarchiv Saarland LaSpey Landesarchiv Speyer LWVH Landeswohlfahrtsverband Hessen MHAP Military Historical Archive, Prague NAA National Archives of Australia NAL National Archives Kew Gardens, London NAW National Archives Washington D.C. OKaW Österreichisches Kriegsarchiv Wein ÖStA Österreichisches Staatsarchiv Vienna PMGO Provost Marshall General’s Office (U.S.A) SaL Staatsarchiv Ludwigsburg SaW Staatsarchiv Würzburg SAB State Archive Bydgoszcz, Poland TBJG Elke Frölich, Die Tagbücher von Joseph Goebbels: Im Auftrag des Institute für Zeitsgeschichte und mit Unterstützung des Staatlichen Archivdienstes Rußlands. Teil II Dikate 1941–1945 (Münich 1995–1996). WLC Weiner Library Collection 191 Notes Introduction: Sippenhaft, Terror and Fear: The Historiography of the Nazi Terror State 1 . Christopher Hutton, Race and the Third Reich: Linguistics, Racial Anthropology and Genetics in the Third Reich (Cambridge 2005), p. 18. 2 . Rosemary O’Kane, Terror, Force and States: The Path from Modernity (Cheltham 1996), p. 19. O’Kane defines a system of terror, as one that is ‘distinguished by summary justice, where the innocence or guilt of the victims is immaterial’. 3 . See Robert Thurston, ‘The Family during the Great Terror 1935–1941’, Soviet Studies , 43, 3 (1991), pp. 553–74. -

Stellvertretung As Vicarious Suffering in Dietrich Bonhoeffer

Stellvertretung as Vicarious Suffering in Dietrich Bonhoeffer This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. by Samuel Paul Randall St. Edmund’s College December 2018 Stellvertretung as Vicarious Suffering in Dietrich Bonhoeffer Abstract Stellvertretung represents a consistent and central hermeneutic for Bonhoeffer. This thesis demonstrates that, in contrast to other translations, a more precise interpretation of Bonhoeffer’s use of Stellvertretung would be ‘vicarious suffering’. For Bonhoeffer Stellvertretung as ‘vicarious suffering’ illuminates not only the action of God in Christ for the sins of the world, but also Christian discipleship as participation in Christ’s suffering for others; to be as Christ: Schuldübernahme. In this understanding of Stellvertretung as vicarious suffering Bonhoeffer demonstrates independence from his Protestant (Lutheran) heritage and reflects an interpretation that bears comparison with broader ecumenical understanding. This study of Bonhoeffer’s writings draws attention to Bonhoeffer’s critical affection towards Catholicism and highlights the theological importance of vicarious suffering during a period of renewal in Catholic theology, popular piety and fictional literature. Although Bonhoeffer references fictional literature in his writings, and indicates its importance in ethical and theological discussion, there has been little attempt to analyse or consider its contribution to Bonhoeffer’s theology. This thesis fills this lacuna in its consideration of the reception by Bonhoeffer of the writings of Georges Bernanos, Reinhold Schneider and Fyodor Dostoevsky. Each of these writers features vicarious suffering, or its conceptual equivalent, as an important motif. According to Bonhoeffer Christian discipleship is the action of vicarious suffering (Stellvertretung) and of Verantwortung (responsibility) in love for others and of taking upon oneself the Schuld that burdens the world.