Colonel Louis Heap O/C 5 SAI & O/C Group 10, Durban 15/02/08 Missing Voices Project Interviewed by Mike Cadman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Publication No. 201619 Notice No. 48 B

CIPC PUBLICATION 16 December 2016 Publication No. 201619 Notice No. 48 B (AR DEREGISTRATIONS – Non Profit Companies) COMPANIES AND CLOSE CORPORATIONS CIPC PUBLICATION NOTICE 19 OF 2016 COMPANIES AND INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY COMMISSION NOTICE IN TERMS OF THE COMPANIES ACT, 2008 (ACT 71 OF 2008) THE FOLLOWING NOTICE RELATING TO THE DEREGISTRATION OF ENTITIES IN TERMS OF SECTION 82 OF THE COMPANIES ACT ARE PUBLISHED FOR GENERAL INFORMATION. THE CIPC WEBSITE AT WWW.CIPC.CO.ZA CAN BE VISITED FOR MORE INFORMATION. NO GUARANTEE IS GIVEN IN RESPECT OF THE ACCURACY OF THE PARTICULARS FURNISHED AND NO RESPONSIBILITY IS ACCEPTED FOR ERRORS AND OMISSIONS OR THE CONSEQUENCES THEREOF. Adv. Rory Voller COMMISSIONER: CIPC NOTICE 19 OF 2016 NOTICE IN TERMS OF SECTION 82 OF THE COMPANIES ACT, 2008 RELATING TO ANNUAL RETURN DEREGISTRATIONS OF COMPANIES AND CLOSE CORPORATIONS K2011100425 SOWETO CITY INVESTMENT AND DEVELOPMENT AGENCY K2011100458 K2011100458 K2011105301 VOICE OF SOLUTION GOSPEL CHURCH K2011105344 BOYES HELPING HANDS K2011105653 RACE 4 CHARITY K2011105678 OYISA FOUNDATION K2011101248 ONE FUTURE DEVELOPMENT 53 K2011101288 EXTRA TIME FOOTBALL SKILLS DEVELOPMENT ORGANISATION K2011108390 HALCYVISION K2011112257 YERUSHALYIM CHRISTIAN CHURCH K2011112598 HOLINERS CHURCH OF CHRIST K2011106676 AMSTIZONE K2011101559 MOLEPO LONG DISTANCE TAXI ASSOCIATION K2011103327 CASHAN X25 HUISEIENAARSVERENIGING K2011118128 JESUS CHRIST HEALS MINISTRY K2011104065 ZWELIHLE MICRO FINANCE COMPANY K2011111623 COVENANT HOUSE MIRACLE CENTRE K2011119146 TSHIAWELO PATRONS COMMUNITY -

Wooltru Healthcare Fund Optical Network List Gauteng

WOOLTRU HEALTHCARE FUND OPTICAL NETWORK LIST GAUTENG PRACTICE TELEPHONE AREA PRACTICE NAME PHYSICAL ADDRESS CITY OR TOWN NUMBER NUMBER ACTONVILLE 456640 JHETAM N - ACTONVILLE 1539 MAYET DRIVE ACTONVILLE 084 6729235 AKASIA 7033583 MAKGOTLOE SHOP C4 ROSSLYN PLAZA, DE WAAL STREET, ROSSLYN AKASIA 012 5413228 AKASIA 7025653 MNISI SHOP 5, ROSSLYN WEG, ROSSLYN AKASIA 012 5410424 AKASIA 668796 MALOPE SHOP 30B STATION SQUARE, WINTERNEST PHARMACY DAAN DE WET, CLARINA AKASIA 012 7722730 AKASIA 478490 BODENSTEIN SHOP 4 NORTHDALE SHOPPING, CENTRE GRAFENHIEM STREET, NINAPARK AKASIA 012 5421606 AKASIA 456144 BODENSTEIN SHOP 4 NORTHDALE SHOPPING, CENTRE GRAFENHIEM STREET, NINAPARK AKASIA 012 5421606 AKASIA 320234 VON ABO & LABUSCHAGNE SHOP 10 KARENPARK CROSSING, CNR HEINRICH & MADELIEF AVENUE, KARENPARK AKASIA 012 5492305 AKASIA 225096 BALOYI P O J - MABOPANE SHOP 13 NINA SQUARE, GRAFENHEIM STREET, NINAPARK AKASIA 087 8082779 ALBERTON 7031777 GLUCKMAN SHOP 31 NEWMARKET MALL CNR, SWARTKOPPIES & HEIDELBERG ROAD, ALBERTON ALBERTON 011 9072102 ALBERTON 7023995 LYDIA PIETERSE OPTOMETRIST 228 2ND AVENUE, VERWOERDPARK ALBERTON 011 9026687 ALBERTON 7024800 JUDELSON ALBERTON MALL, 23 VOORTREKKER ROAD, ALBERTON ALBERTON 011 9078780 ALBERTON 7017936 ROOS 2 DANIE THERON STREET, ALBERANTE ALBERTON 011 8690056 ALBERTON 7019297 VERSTER $ VOSTER OPTOM INC SHOP 5A JACQUELINE MALL, 1 VENTER STREET, RANDHART ALBERTON 011 8646832 ALBERTON 7012195 VARTY 61 CLINTON ROAD, NEW REDRUTH ALBERTON 011 9079019 ALBERTON 7008384 GLUCKMAN 26 VOORTREKKER STREET ALBERTON 011 9078745 -

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report: Volume 2

VOLUME TWO Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report The report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was presented to President Nelson Mandela on 29 October 1998. Archbishop Desmond Tutu Ms Hlengiwe Mkhize Chairperson Dr Alex Boraine Mr Dumisa Ntsebeza Vice-Chairperson Ms Mary Burton Dr Wendy Orr Revd Bongani Finca Adv Denzil Potgieter Ms Sisi Khampepe Dr Fazel Randera Mr Richard Lyster Ms Yasmin Sooka Mr Wynand Malan* Ms Glenda Wildschut Dr Khoza Mgojo * Subject to minority position. See volume 5. Chief Executive Officer: Dr Biki Minyuku I CONTENTS Chapter 1 Chapter 6 National Overview .......................................... 1 Special Investigation The Death of President Samora Machel ................................................ 488 Chapter 2 The State outside Special Investigation South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 42 Helderberg Crash ........................................... 497 Special Investigation Chemical and Biological Warfare........ 504 Chapter 3 The State inside South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 165 Special Investigation Appendix: State Security Forces: Directory Secret State Funding................................... 518 of Organisations and Structures........................ 313 Special Investigation Exhumations....................................................... 537 Chapter 4 The Liberation Movements from 1960 to 1990 ..................................................... 325 Special Investigation Appendix: Organisational structures and The Mandela United -

Ireland and the South African War, 1899-1902 by Luke Diver, M.A

Ireland and the South African War, 1899-1902 By Luke Diver, M.A. THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF PH.D. DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF IRELAND MAYNOOTH Head of Department: Professor Marian Lyons Supervisors of Research: Dr David Murphy Dr Ian Speller 2014 i Table of Contents Page No. Title page i Table of contents ii Acknowledgements iv List of maps and illustrations v List of tables in main text vii Glossary viii Maps ix Personalities of the South African War xx 'A loyal Irish soldier' xxiv Cover page: Ireland and the South African War xxv Introduction 1 Chapter 1: Irish soldiers’ experiences in South Africa (October - December 1899) 19 Chapter 2: Irish soldiers’ experiences in South Africa (January - March 1900) 76 Chapter 3: The ‘Irish’ Imperial Yeomanry and the battle of Lindley 109 Chapter 4: The Home Front 152 Chapter 5: Commemoration 198 Conclusion 227 Appendix 1: List of Irish units 240 Appendix 2: Irish Victoria Cross winners 243 Appendix 3: Men from Irish battalions especially mentioned from General Buller for their conspicuous gallantry in the field throughout the Tugela Operations 247 ii Appendix 4: General White’s commendations of officers and men that were Irish or who were attached to Irish units who served during the period prior and during the siege of Ladysmith 248 Appendix 5: Return of casualties which occurred in Natal, 1899-1902 249 Appendix 6: Return of casualties which occurred in the Cape, Orange River, and Transvaal Colonies, 1899-1902 250 Appendix 7: List of Irish officers and officers who were attached -

The Role of Non-Whites in the South African Defence Force by Cmdt C.J

Scientia Militaria, South African Journal of Military Studies, Vol 16, Nr 2, 1986. http://scientiamilitaria.journals.ac.za The Role of Non-Whites in the South African Defence Force by Cmdt C.J. N6thling* assisted by Mrs L. 5teyn* The early period for Blacks, Coloureds and Indians were non- existent. It was, however, inevitable that they As long ago as 1700, when the Cape of Good would be resuscitated when war came in 1939. Hope was still a small settlement ruled by the Dutch East India Company, Coloureds were As war establishment tables from this period subject to the same military duties as Euro- indicate, Non-Whites served as separate units in peans. non-combatant roles such as drivers, stretcher- bearers and batmen. However, in some cases It was, however, a foreign war that caused the the official non-combatant edifice could not be establishment of the first Pandour regiment in maintained especially as South Africa's shortage 1781. They comprised a force under white offi- of manpower became more acute. This under- cers that fought against the British prior to the lined the need for better utilization of Non-Whites occupation of the Cape in 1795. Between the in posts listed on the establishment tables of years 1795-1803 the British employed white units and a number of Non-Whites were Coloured soldiers; they became known as the subsequently attached to combat units and they Cape Corps after the second British occupation rendered active service, inter alia in an anti-air- in 1806. During the first period of British rule craft role. -

The Role and Application of the Union Defence Force in the Suppression of Internal Unrest, 1912 - 1945

THE ROLE AND APPLICATION OF THE UNION DEFENCE FORCE IN THE SUPPRESSION OF INTERNAL UNREST, 1912 - 1945 Andries Marius Fokkens Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Military Science (Military History) at the Military Academy, Saldanha, Faculty of Military Science, Stellenbosch University. Supervisor: Lieutenant Colonel (Prof.) G.E. Visser Co-supervisor: Dr. W.P. Visser Date of Submission: September 2006 ii Declaration I, the undersigned, hereby declare that the work contained in this thesis is my own original work and that I have not previously submitted it, in its entirety or in part, to any university for a degree. Signature:…………………….. Date:………………………….. iii ABSTRACT The use of military force to suppress internal unrest has been an integral part of South African history. The European colonisation of South Africa from 1652 was facilitated by the use of force. Boer commandos and British military regiments and volunteer units enforced the peace in outlying areas and fought against the indigenous population as did other colonial powers such as France in North Africa and Germany in German South West Africa, to name but a few. The period 1912 to 1945 is no exception, but with the difference that military force was used to suppress uprisings of white citizens as well. White industrial workers experienced this military suppression in 1907, 1913, 1914 and 1922 when they went on strike. Job insecurity and wages were the main causes of the strikes and militant actions from the strikers forced the government to use military force when the police failed to maintain law and order. -

E2b BA1&2 Database (Surnames Sept 2019).Pdf

N3 BATCH 1 ‐ BA2 (SURNAMES ‐ SEPTEMBER 2019) Title First Names Surname Position Co/Org Address Address 2 Address 3 City Postcode Tel Fax E-mail Madam/Sir [email protected] Madam/Sir 16 Tulip Avenue Dunveria 3201 033-391 2048 / 033-391 7860 Madam/Sir The Director Abbot Francis Realty P O BOX 1510 20 Lancaster Terrace, Westville Westville Durban 3630 031 266 0680 [email protected] Madam/Sir The Directors Afrocon Construction P O Box: 531 3 Torlage Street, New Germany , 3610 New Germany Durban 3620 031 817 2600 [email protected] Madam/Sir The Director Alenti 84 P O Box: 2781 Westway 3630 Madam/Sir The Directors Arvoflex Unit 2 54 Brickworks Way Briardene Durban Madam/Sir Ashley Sports Club 10 Russell Street Ashley Pinetown 3610 031 709 2188 [email protected] Madam/Sir Assmang Manganese Cato Ridge Works Ltd 1 Eddie Hagan Drive, Camperdown Cato Ridge 3680 031 7825000 031 7825096 [email protected] Madam/Sir Directors Auto Armor Pinetown 1-5 Stockville Rd, Marianhill Pinetown 3610 031 700 1270 Madam/Sir The Director Azma Investments 30 Greenfern Road Mobeni Heights Durban 4092 Madam/Sir The Director Bal Logistics P O Box: 49086 East End 4018 Madam/Sir Bears Pre-Primary School 11 Adams Road Ashley Pinetown 3616 031 700 3343 [email protected] Madam/Sir The Directors Born Free Investments 385 P O Box: 2781 Westway 3634 Madam/Sir The Director Brendi Management P O Box: 201966 Durban North 4016 Madam/Sir The Directors Cabris Property Holdings P O Box: 1489 Pinetown 3600 Madam/Sir Calm Valley Trading Pty -

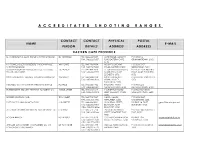

Accreditated Shooting Ranges

A C C R E D I T A T E D S H O O T I N G R A N G E S CONTACT CONTACT PHYSICAL POSTAL NAME E-MAIL PERSON DETAILS ADDRESS ADDRESS EASTERN CAPE PROVINCE D J SURRIDGE T/A ALOE RIDGE SHOOTING RANGE DJ SURRIDGE TEL: 046 622 9687 ALOE RIDGE MANLEY'S P O BOX 12, FAX: 046 622 9687 FLAT, EASTERN CAPE, GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 6140 K V PEINKE (SOLE PROPRIETOR) T/A BONNYVALE WK PEINKE TEL: 043 736 9334 MOUNT COKE KWT P O BOX 5157, SHOOTING RANGE FAX: 043 736 9688 ROAD, EASTERN CAPE GREENFIELDS, 5201 TOMMY BOSCH AND ASSOCIATES CC T/A LOCK, T C BOSCH TEL: 041 484 7818 51 GRAHAMSTAD ROAD, P O BOX 2564, NOORD STOCK AND BARREL FAX: 041 484 7719 NORTH END, PORT EINDE, PORT ELIZABETH, ELIZABETH, 6056 6056 SWALLOW KRANTZ FIREARM TRAINING CENTRE CC WH SCOTT TEL: 045 848 0104 SWALLOW KRANTZ P O BOX 80, TARKASTAD, FAX: 045 848 0103 SPRING VALLEY, 5370 TARKASTAD, 5370 MECHLEC CC T/A OUTSPAN SHOOTING RANGE PL BAILIE TEL: 046 636 1442 BALCRAIG FARM, P O BOX 223, FAX: 046 636 1442 GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 BUTTERWORTH SECURITY TRAINING ACADEMY CC WB DE JAGER TEL: 043 642 1614 146 BUFFALO ROAD, P O BOX 867, KING FAX: 043 642 3313 KING WILLIAM'S TOWN, WILLIAM'S TOWN, 5600 5600 BORDER HUNTING CLUB TE SCHMIDT TEL: 043 703 7847 NAVEL VALLEY, P O BOX 3047, FAX: 043 703 7905 NEWLANDS, 5206 CAMBRIDGE, 5206 EAST CAPE PLAINS GAME SAFARIS J G GREEFF TEL: 046 684 0801 20 DURBAN STREET, PO BOX 16, FORT [email protected] FAX: 046 684 0801 BEAUFORT, FORT BEAUFORT, 5720 CELL: 082 925 4526 BEAUFORT, 5720 ALL ARMS FIREARM ASSESSMENT AND TRAINING CC F MARAIS TEL: 082 571 5714 -

National Liquor Authority Register

NATIONAL LIQUOR AUTHORITY REGISTER - 30 JUNE 2013 Registration Registered Person Trading Name Activities Registered Person's Principal Place Of Business Province Date of Transfer & (or) Date of Number Permitted Registration Relocations Cancellation RG 0006 The South African Breweries Limited Sab -(Gauteng) M & D 3 Fransen Str, Chamber GP 2005/02/24 N/A N/A RG 0007 Greytown Liquor Distributors Greytown Liquor Distributors D Lot 813, Greytown, Durban KZN 2005/02/25 N/A N/A RG 0008 Expo Liquor Limited Expo Liquor Limited (Groblersdal) D 16 Linbri Avenue, Groblersdal, 0470 MPU N/A 28/01/2011 RG 0009 Expo Liquor Limited Expo Liquor Limited (Ga D Stand 14, South Street, Ga-Rankuwa, 0208 NW N/A 27/09/2011 Rankuwa) RG 0010 The South African Breweries Limited Sab (Port Elizabeth) M & D 47 Kohler Str, Perseverence, Port Elizabeth EC 2005/02/24 N/A N/A RG 0011 Lutzville Vineyards Ko-Op Ltd Lutzville Vineyards Ko-Op Ltd M & D Erf 312 Kuils River, Pinotage Str, WC 2008/02/20 N/A N/A Saxenburg Park, Kuils River RG 0012 Louis Trichardt Beer Wholesalers (Pty) Louis Trichardt Beer Wholesalers D Erf 05-04260, Byles Street, Industrial Area, LMP 2005/06/05 N/A N/A Ltd Louis Trichardt, Western Cape RG 0013 The South African Breweries Limited Sab ( Newlands) M & D 3 Main Road, Newlands WC 2005/02/24 N/A N/A RG 0014 Expo Liquor Limited Expo Liquor Limited (Rustenburg) D Erf 1833, Cnr Ridder & Bosch Str, NW 2007/10/19 02/03/2011 Rustenburg RG 0015 Madadeni Beer Wholesalers (Pty) Ltd Madadeni Beer Wholesalers (Pty) D Lot 4751 Section 7, Madadeni, Newcastle, KZN -

The Battle of Congella

REMEMBERING DURBAN’S HISTORICAL TAPESTRY – THE BATTLE OF CONGELLA Researched and written by Udo Richard AVERWEG Tuesday 23rd May 2017 marks an important date in Durban’s historical tapestry – it is the dodransbicentennial (175th) anniversary of the commencement of the Battle of Congella in the greater city of Durban. From a military historical perspective, the Congella battle site was actually named after former Zulu barracks (known as an ikhanda), called kwaKhangela. This was established by King Shaka kaSenzangakhona (ca. 1787 – 1828) to keep a watchful eye on the nearby British traders at Port Natal - the full name of the place was kwaKhangela amaNkengane (‘place of watching over vagabonds’). Shortly after the Battle of Blood River (isiZulu: iMpi yaseNcome) on 16th December 1838, Natalia Republiek was established by the migrant Voortrekkers (Afrikaner Boers, mainly of Dutch descent). It stretched from the Tugela River to the north to present day Port St Johns at the UMzimvubu River to the south. The Natalia Republiek was seeking an independent port of entry, free from British control by conquering the Port Natal trading settlement, which had been settled by mostly British traders on the modern-day site of Durban. However, the governor of the Cape Province, Maj Gen Sir George Thomas Napier KCB (1784 - 1855), stated that his intention was to take military possession of Port Natal and prevent the Afrikaner Boers establishing an independent republic upon the coast with a harbour through which access to the interior could be gained. The Battle of Congella began on 23rd May 1842 between British troops from the Cape Colony and the Afrikaner Boer forces of the Natalia Republiek. -

National Liquor Authority Register

National Liquor Register Q1 2021 2022 Registration/Refer Registered Person Trading Name Activities Registered Person's Principal Place Of Business Province Date of Registration Transfer & (or) Date of ence Number Permitted Relocations or Cancellation alterations Ref 10 Aphamo (PTY) LTD Aphamo liquor distributor D 00 Mabopane X ,Pretoria GP 2016-09-05 N/A N/A Ref 12 Michael Material Mabasa Material Investments [Pty] Limited D 729 Matumi Street, Montana Tuine Ext 9, Gauteng GP 2016-07-04 N/A N/A Ref 14 Megaphase Trading 256 Megaphase Trading 256 D Erf 142 Parkmore, Johannesburg, GP 2016-07-04 N/A N/A Ref 22 Emosoul (Pty) Ltd Emosoul D Erf 842, 845 Johnnic Boulevard, Halfway House GP 2016-10-07 N/A N/A Ref 24 Fanas Group Msavu Liquor Distribution D 12, Mthuli, Mthuli, Durban KZN 2018-03-01 N/A 2020-10-04 Ref 29 Golden Pond Trading 476 (Pty) Ltd Golden Pond Trading 476 (Pty) Ltd D Erf 19, Vintonia, Nelspruit MP 2017-01-23 N/A N/A Ref 33 Matisa Trading (Pty) Ltd Matisa Trading (Pty) Ltd D 117 Foresthill, Burgersfort LMP 2016-09-05 N/A N/A Ref 34 Media Active cc Media Active cc D Erf 422, 195 Flamming Rock, Northriding GP 2016-09-05 N/A N/A Ref 52 Ocean Traders International Africa Ocean Traders D Erf 3, 10608, Durban KZN 2016-10-28 N/A N/A Ref 69 Patrick Tshabalala D Bos Joint (PTY) LTD D Erf 7909, 10 Comorant Road, Ivory Park GP 2016-07-04 N/A N/A Ref 75 Thela Management PTY LTD Thela Management PTY LTD D 538, Glen Austin, Midrand, Johannesburg GP 2016-04-06 N/A 2020-09-04 Ref 78 Kp2m Enterprise (Pty) Ltd Kp2m Enterprise D Erf 3, Cordell -

The Times History of the War in South Africa, 1899-1902;

aia of The War in South Africa of The War in South Africa 1899-1902 Edited by L. S. Amery Fellow of All Souls With many Photogravure and other Portraits, Maps and Battle Plans Vol. VII Index and Appendices LONDON SAMPSON Low, MARSTON AND COMPANY, LTD. loo, SOUTHWARK STREET, S.E. 1909 LONDON : PRINTED BY WILLIAM CLOWES AND SONS, LIMITED, DUKE STREET, STAMFORD STREET, S.E., AND GREAT WINDMILL STREET, W PREFACE THE various appendices and the index which make up the present volume are the work of Mr. G. P. Tallboy, who has acted as secretary to the History for the last seven years, and whom I have to thank not only for the labour and research comprised in this volume, but for much useful assistance in the past. The index will, I hope, prove of real service to students of the war. The general principles on which it has been compiled are those with which the index to The Times has familiarized the public. The very full bibliography which Mr. Tallboy has collected may give the reader some inkling of the amount of work involved in the composition of this history. I cannot claim to have actually read all the works comprised in the list, though I think there are comparatively few among them that have not been consulted. On the other hand the list does not include the blue-books, despatches, magazine and newspaper articles, and, above all, private diaries, narratives and notes, which have formed the real bulk of my material. L. S. AMERY. CONTENTS APPENDIX I PAGE.