Michelangelo (1475 - 1564)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Master of the Unruly Children and His Artistic and Creative Identities

The Master of the Unruly Children and his Artistic and Creative Identities Hannah R. Higham A Thesis Submitted to The University of Birmingham For The Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Art History, Film and Visual Studies School of Languages, Art History and Music College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham May 2015 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis examines a group of terracotta sculptures attributed to an artist known as the Master of the Unruly Children. The name of this artist was coined by Wilhelm von Bode, on the occasion of his first grouping seven works featuring animated infants in Berlin and London in 1890. Due to the distinctive characteristics of his work, this personality has become a mainstay of scholarship in Renaissance sculpture which has focused on identifying the anonymous artist, despite the physical evidence which suggests the involvement of several hands. Chapter One will examine the historiography in connoisseurship from the late nineteenth century to the present and will explore the idea of the scholarly “construction” of artistic identity and issues of value and innovation that are bound up with the attribution of these works. -

Terracotta Tableau Sculpture in Italy, 1450-1530

PALPABLE POLITICS AND EMBODIED PASSIONS: TERRACOTTA TABLEAU SCULPTURE IN ITALY, 1450-1530 by Betsy Bennett Purvis A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy Department of Art University of Toronto ©Copyright by Betsy Bennett Purvis 2012 Palpable Politics and Embodied Passions: Terracotta Tableau Sculpture in Italy, 1450-1530 Doctorate of Philosophy 2012 Betsy Bennett Purvis Department of Art University of Toronto ABSTRACT Polychrome terracotta tableau sculpture is one of the most unique genres of 15th- century Italian Renaissance sculpture. In particular, Lamentation tableaux by Niccolò dell’Arca and Guido Mazzoni, with their intense sense of realism and expressive pathos, are among the most potent representatives of the Renaissance fascination with life-like imagery and its use as a powerful means of conveying psychologically and emotionally moving narratives. This dissertation examines the versatility of terracotta within the artistic economy of Italian Renaissance sculpture as well as its distinct mimetic qualities and expressive capacities. It casts new light on the historical conditions surrounding the development of the Lamentation tableau and repositions this particular genre of sculpture as a significant form of figurative sculpture, rather than simply an artifact of popular culture. In terms of historical context, this dissertation explores overlooked links between the theme of the Lamentation, the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem, codes of chivalric honor and piety, and resurgent crusade rhetoric spurred by the fall of Constantinople in 1453. Reconnected to its religious and political history rooted in medieval forms of Sepulchre devotion, the terracotta Lamentation tableau emerges as a key monument that both ii reflected and directed the cultural and political tensions surrounding East-West relations in later 15th-century Italy. -

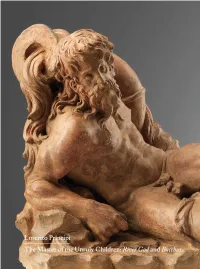

The Master of the Unruly Children: River God and Bacchus TRINITY

TRINITY FINE ART Lorenzo Principi The Master of the Unruly Children: River God and Bacchus London February 2020 Contents Acknowledgements: Giorgio Bacovich, Monica Bassanello, Jens Burk, Sara Cavatorti, Alessandro Cesati, Antonella Ciacci, 1. Florence 1523 Maichol Clemente, Francesco Colaucci, Lavinia Costanzo , p. 12 Claudia Cremonini, Alan Phipps Darr, Douglas DeFors , 2. Sandro di Lorenzo Luizetta Falyushina, Davide Gambino, Giancarlo Gentilini, and The Master of the Unruly Children Francesca Girelli, Cathryn Goodwin, Simone Guerriero, p. 20 Volker Krahn, Pavla Langer, Guido Linke, Stuart Lochhead, Mauro Magliani, Philippe Malgouyres, 3. Ligefiguren . From the Antique Judith Mann, Peta Motture, Stefano Musso, to the Master of the Unruly Children Omero Nardini, Maureen O’Brien, Chiara Padelletti, p. 41 Barbara Piovan, Cornelia Posch, Davide Ravaioli, 4. “ Bene formato et bene colorito ad imitatione di vero bronzo ”. Betsy J. Rosasco, Valentina Rossi, Oliva Rucellai, The function and the position of the statuettes of River God and Bacchus Katharina Siefert, Miriam Sz ó´cs, Ruth Taylor, Nicolas Tini Brunozzi, Alexandra Toscano, Riccardo Todesco, in the history of Italian Renaissance Kleinplastik Zsófia Vargyas, Laëtitia Villaume p. 48 5. The River God and the Bacchus in the history and criticism of 16 th century Italian Renaissance sculpture Catalogue edited by: p. 53 Dimitrios Zikos The Master of the Unruly Children: A list of the statuettes of River God and Bacchus Editorial coordination: p. 68 Ferdinando Corberi The Master of the Unruly Children: A Catalogue raisonné p. 76 Bibliography Carlo Orsi p. 84 THE MASTER OF THE UNRULY CHILDREN probably Sandro di Lorenzo di Smeraldo (Florence 1483 – c. 1554) River God terracotta, 26 x 33 x 21 cm PROVENANCE : heirs of the Zalum family, Florence (probably Villa Gamberaia) THE MASTER OF THE UNRULY CHILDREN probably Sandro di Lorenzo di Smeraldo (Florence 1483 – c. -

A Florentine Diary

THE LIBRARIES A FLORENTINE DIARY A nderson SAVONAROLA From the portrait by Fra Bartolomeo. A FLORENTINE DIARY FROM 1450 TO 1516 BY LUCA LANDUCCI CONTINUED BY AN ANONYMOUS WRITER TILL 1542 WITH NOTES BY IODOCO DEL B A D I A 0^ TRANSLATED FROM THE ITALIAN BY ALICE DE ROSEN JERVIS & PUBLISHED IN LONDON IN 1927 By J. M. DENT & SONS LTD. •8 *« AND IN NEW YORK BY « « E. P. DUTTON & COMPANY TRANSLATOR'S PREFACE ALTHOUGH Del Badia's ample and learned notes are sufficient for an Italian, it seemed to me that many allu sions might be puzzling to an English reader, especially to one who did not know Florence well; therefore I have added short notes on city-gates, churches and other buildings which now no longer exist; on some of the festivals and customs; on those streets which have changed their nomenclature since Landucci's, day; and also on the old money. His old-fashioned spelling of names and places has been retained (amongst other peculiarities the Florentine was in the habit of replacing an I by an r) ; also the old calendar; and the old Florentine method of reckoning the hours of the day (see notes to 12 January, 1465, and to 27 April, 1468). As for the changes in the Government, they were so frequent and so complex, that it is necessary to have recourse to a consecutive history in order to under stand them. A. DE R. J. Florence 1926. The books to which I am indebted are as follows: Storia della Repubblica di Firenze (2 vols.), Gino Capponi. -

Lives of the Most Eminent Painters Sculptors and Architects

Lives of the Most Eminent Painters Sculptors and Architects Giorgio Vasari Lives of the Most Eminent Painters Sculptors and Architects Table of Contents Lives of the Most Eminent Painters Sculptors and Architects.......................................................................1 Giorgio Vasari..........................................................................................................................................2 LIFE OF FILIPPO LIPPI, CALLED FILIPPINO...................................................................................9 BERNARDINO PINTURICCHIO........................................................................................................13 LIFE OF BERNARDINO PINTURICCHIO.........................................................................................14 FRANCESCO FRANCIA.....................................................................................................................17 LIFE OF FRANCESCO FRANCIA......................................................................................................18 PIETRO PERUGINO............................................................................................................................22 LIFE OF PIETRO PERUGINO.............................................................................................................23 VITTORE SCARPACCIA (CARPACCIO), AND OTHER VENETIAN AND LOMBARD PAINTERS...........................................................................................................................................31 -

'Touch the Truth'?: Desiderio Da Settignano, Renaissance Relief And

Wright, AJ; (2012) 'Touch the Truth'? Desiderio da Settignano, Renaissance relief and the body of Christ. Sculpture Journal, 21 (1) pp. 7-25. 10.3828/sj.2012.2. Downloaded from UCL Discovery: http://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/1356576/. ARTICLE ‘Touch the truth’?: Desiderio da Settignano, Renaissance relief and the body of Christ Alison Wright School of Arts and Social Sciences, University College London From the late nineteenth century, relief sculpture has been taken as a locus classicus for understanding new engagements with spatial and volumetric effects in the art of fifteenth- century Florence, with Ghiberti usually taking the Academy award for the second set of Baptistery doors.1 The art historical field has traditionally been dominated by German scholarship both in artist-centred studies and in the discussion of the so-called ‘malerischens Relief’.2 An alternative tradition, likewise originating in the nineteenth-century, has been claimed by English aesthetics where relief has offered a place of poetic meditation and insight. John Ruskin memorably championed the chromatic possibilities of low relief architectural carving in The Stones of Venice (early 1850s) and in his 1872 essay on Luca della Robbia Walter Pater mused on how ‘resistant’ sculpture could become a vehicle of expression.3 For Adrian Stokes (1934) the very low relief figures by Agostino di Duccio at the Tempio Malatestiano in Rimini represented a vital ‘blooming’ of luminous limestone.4 Stokes’ insistence that sculptural values were not reducible to modelling, which he identified -

PIAZZA SIGNORIA E DINTORNI Centro Storico Di Firenze Inscritto Nella Lista Del Patrimonio Mondiale Nel 1982 SOMMARIO / TABLE of CONTENTS

PIAZZA SIGNORIA E DINTORNI Centro Storico di Firenze inscritto nella Lista del Patrimonio Mondiale nel 1982 SOMMARIO / TABLE OF CONTENTS Storia History 4 Itinerario Itinerary 7 Approfondimenti Further Insights 21 Informazioni Information 55 HISTORY In questa visita ti porteremo attraverso il Centro Storico a spasso nel cuore politico e commerciale della città, in alcune delle piazze più belle di Firenze, da piazza della Repubblica a piazza della Signoria. Questa area era una delle più caratteristiche di Firenze, punteggiata non solo di chiese, tabernacoli, torri medievali, palazzi nobiliari, ma anche di botteghe storiche e delle sedi delle corporazioni delle Arti. Avevano qui sede soprattutto botteghe di abbigliamento e di calzature, ma anche laboratori di artisti come Donatello e Michelozzo. Traccia di questa antica presenza sono, ad esempio, le monumentali statue delle nicchie di Orsanmichele, ciascuna dedicata ai rispettivi santi protettori delle diverse Arti e opera di grandi scultori come Donatello, Verrocchio, Ghiberti e Giambologna. L’intera area subì pesanti trasformazioni a fine Ottocento, in occasione di Firenze capitale d’Italia, trasformazioni che interessarono non soltanto piazza della Repubblica, ma anche via dei Calzaiuoli, sottoposta a diversi progetti di ampliamento. Piazza della Repubblica, centro nevralgico fin da epoca romana, che aveva mantenuto durante tutto il Medioevo la funzione di luogo di ritrovo destinato al commercio, vide stravolto il proprio assetto. A conservare in gran parte, invece, il proprio antico aspetto è stata piazza della Signoria, zona di grande importanza fin dall’epoca romana, i cui resti sono ancora oggi visitabili sotto Palazzo Vecchio. La piazza iniziò ad assumere l’attuale forma intorno al 1268, in seguito alla demolizione delle case dei Ghibellini da parte dei Guelfi vincitori. -

Agon Y Ecstasy

The AGON Y and The ECSTASY A BIOGRAPHICAL NOVEL OF MICHELANGELO IRVING STONE A SIGNET BOOK For my wife JEAN STONE Diaskeuast Possibly, the world’s best SIGNET Published by New American Library, a division of Penguin Putnam Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A. Penguin Books Ltd, 27 Wrights Lane, London W8 5TZ, England Penguin Books Australia Ltd, Ringwood, Victoria, Australia Penguin Books Canada Ltd,10 Alcorn Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4V 3B2 Penguin Books (N.Z.) Ltd, 182-190 Wairau Road, Auckland 10, New Zealand Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England Published by Signet, an imprint of New American Library, a division of Penguin Putnam Inc. This is an authorized reprint of a hardcover edition published by Doubleday & Company, Inc., 54 53 52 51 50 Copyright © 1961 by Doubleday & Company, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission. For information address Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing; Inc. 666 Fifth Avenue, New York, New York 10103. The eighteen lines from Ovid’s The Metamorphoses, translated by Horace Grega ory, are reprinted by permission. Copyright © 1958 by The Viking Press, Inc. Forty-five lines from Dante’s Divine Comedy, translated by Lawrence Grant White, are reprinted by permission of the publisher. Copyright 1948 by Pan theon Books. REGISTERED TRADEMARK—MARCA REGISTRADA Printed in the United States of America If you purchased this book without a cover you should be aware that this book is stolen property. It -

Carolyn's Guide to Florence and Its

1 Carolyn’s Guide to Be selective Florence and Its Art San Frediano Castello See some things well rather than undertaking the impossible task of capturing it all. It is helpful, even if seeming compulsive, to create a day planner (day and hour grid) and map of what you want to see. Opening hours and days for churches and museums vary, and “The real voyage of discovery consists not in it’s all too easy to miss something because of timing. seeking new landscapes but in having new eyes.” I make a special effort to see works by my fa- vorite artists including Piero della Francesca, Masac- Marcel Proust, Remembrance of Things Past cio, Titian, Raphael, Donatello, Filippo Lippi, Car- avaggio, and Ghirlandaio. I anticipate that it won’t be long before you start your own list. Carolyn G. Sargent February 2015, New York 2 For Tom, my partner on this voyage of discovery. With special thanks to Professoressa d’arte Rosanna Barbiellini-Amidei. Contents 1 Introduction 5 1.1 TheQuattrocento ............................................... 5 1.2 Reflections of Antiquity . 8 1.3 Perspective, A Tool Regained . 10 1.4 CreatorsoftheNewArt............................................ 10 1.5 IconographyandIcons............................................. 13 1.6 The Golden Legend ............................................... 13 1.7 Angels and Demons . 14 1.8 TheMedici ................................................... 15 2 Churches 17 2.1 Duomo (Santa Maria del Fiore) . 17 2.2 Orsanmichele . 21 2.3 Santa Maria Novella . 22 2.4 Ognissanti . 25 2.5 Santa Trinita . 26 2.6 San Lorenzo . 28 2.7 San Marco . 30 2.8 SantaCroce .................................................. 32 2.9 Santa Felicita . 35 2.10 San Miniato al Monte . -

Centri Fisioterapia Convenzionati

CENTRI FISIOTERAPIA CONVENZIONATI PR CITTA' CAP RAGIONE SOCIALE INDIRIZZO TELEFONO AR AREZZO 52100 OLYMPIA MEDICAL CENTER VIA CARLO DONAT CATTIN 125 0575040081 S.R.L. FI FIRENZE 50013 NOBILI EMANUELE - VIA GUELFA 116 3403942747 GUELFA FI SCANDICCI 50018 NOBILI EMANUELE - PIAZZA MATTEOTTI 8 3403942747 SCANDICCI FI IMPRUNETA 50023 FISIOLAB 2.0 VIA IMPRUNETANA PER 3279009905 POLIAMBULATORIO TAVERNELLE 231 FI CASTELFIORENTINO 50051 ORABONA CIRO VIA PIAVE 47 0571680585 FI FIRENZE 50125 CENTRO GIUSTI - VIA DEL GELSOMINO 60 0552322698 FLORENTIA SRL FI FIRENZE 50127 OLIVIERO LUCA - FIRENZE PIAZZA PIETRO MASCAGNI 4 FI FIRENZE 50127 NOBILI EMANUELE - ALFIERI VIA CARLO ALFIERI DI SOSTEGNO 9 3403942747 FI FIRENZE 50136 PAOLINI STEFANO VIA SCIPIONE AMMIRATO 38 3683347011 1 / 17 CENTRI FISIOTERAPIA CONVENZIONATI PR CITTA' CAP RAGIONE SOCIALE INDIRIZZO TELEFONO FI FIRENZE 50136 FISIOTECH LAB SRL VIA GIOVANNI LANZA 56 0559060139 FI FIRENZE 50142 FISIONER DI LAPO RAUGEI E VIA ADRIANO CECIONI 117 0550672455 C SAS FI FIRENZE 50142 ZERINI MARTINA VIA E. DE FABRIS 18 3331089979 FI FIRENZE 50142 MILIANI ILARIA VIA BACCIO DA MONTELUPO 73/E 3286511677 FI FIRENZE 50142 CAMBI CESARE - ZERO9 VIA PALAZZO DEI DIAVOLI 101 -103 3392403651 STUDIO DI FISIOTERAPIA FI FIRENZE 50142 ACCIAI GIULIA VIA EMILIO DE FABRIS 18 3331089979 FI FIRENZE 50142 BASSINI BENEDETTA VIA E. DE FABRIS 18 3331089979 FI FIRENZE 50144 F.G.P. SRL VIA DEL PONTE DELLE MOSSE 0550163392 15B/17/B LI CECINA 57023 DONATI SIMONE E C SNC VIA GORI 7/A 05861630745 2 / 17 CENTRI FISIOTERAPIA CONVENZIONATI PR CITTA' CAP RAGIONE SOCIALE INDIRIZZO TELEFONO LU FORTE DEI MARMI 55042 CASA DI CURA SAN VIA PADRE IGNAZIO DA CARRARA 37 0584739338 CAMILLO FORTE DEI MARM. -

___1 Giorgio Vasari, Cosimo I De ̓ Medici with His Architects

____ 1 Giorgio Vasari, Cosimo I de ̓ Medici with his architects, engineers and sculptors. Florence, Palazzo Vecchio, Sala di Cosimo I “MaeSTRI D’alCUNE ARTI MISTE E D’INGEGNO” ARTISTS AND ARTISANS IN THE COMPAGNIA DELLO SCALZO Alana O’Brien Giorgio Vasari, in the Sala di Cosimo I, painted the men of the Compagnia dello Scalzo, who com- a tondo depicting missioned from Andrea del Sarto a cycle representing Duke Cosimo (ca. 1555;I de’ Medici surroundedFig. 1). Of by the for their cloister, he char- thehis architects, ten individuals engineers and gathered sculptors in surprising intimacy acterizedLife of themsaint Johnas “personethe Baptist basse” – people of a low around the Duke, five belonged – or would belong – socio-economic status – and as “più ricchi d’animo to the Compagnia di San Giovanni Battista commonly che di danari”.2 Perhaps echoing Vasari’s assessment, called “lo Scalzo”: Tribolo, Giovanni Battista del Tas- the Scalzo’s membership has since been characterized so, Davide Fortini, Nanni di Unghero and Benvenu- as comprising ‘anonymous’ and ‘uncultured’ artisans, to Cellini.1 Curiously though, when Vasari described such as candle makers, food vendors, cobblers, furriers, 1 Vasari identified all except Fortini (Giorgio Vasari, in: , I–III [1997], pp. 81–100: 84; Elizabeth Pil- Le vite de’ più eccellenti pit- Miscellanea storica della Valdelsa , ed. by Gaetano Milanesi, Florence 1906, VIII, p. 192). liod, “Representation, Misrepresentation, and Non-Representation”, in: tori, scultori ed architettori Vasa- For their placement see William Chandler Kirwin, “Vasari’s tondo of ‘Cosi- , ed. by Philip Jacks, Cambridge ri’s Florence: Artists and Literati at the Medicean Court mo I with his Architects, Engineers, and Sculptors’ in the Palazzo Vecchio: 1998, pp. -

Roscoe and Italy the Reception of Italian Renaissance History and Culture in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries

Now available from Ashgate Publishing… Roscoe and Italy The Reception of Italian Renaissance History and Culture in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries Edited by Stella Fletcher In 1795 William Roscoe (1753–1831) published a biography of Contents: Introduction, Stella Fletcher; PART I ROSCOE AND THE REVIVAL Lorenzo de’ Medici, which proved so popular that it prompted claims OF THE ARTS: Between history and art history: Roscoe’s Medici Lives, that Roscoe had effectively invented the Italian Renaissance as it has Emanuele Pellegrini; Roscoe’s Lorenzo: ‘restorer of Italian literature, been known by subsequent generations of readers in the English- Corinna Salvadori Lonergan; Roscoe’s Italian paintings in the speaking world. Despite such enthusiastic assertions, however, this Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, Xanthe Brooke. PART II ROSCOE AS collection of essays is the first systematic attempt to examine Roscoe BIOGRAPHER: William Roscoe and his Lorenzo de’ Medici, and his contribution towards modern conceptions of the Renaissance. Cecil H. Clough; William Roscoe and Lorenzo de’ Medici as Covering a range of subjects from art history and literature, to politics statesman, John E. Law; William Roscoe’s Life of Leo X and and culture, the volume provides a fascinating picture both of Roscoe correspondence with Angelo Fabroni, D.S. Chambers. PART III THE and his historical legacy. ROSCOE CIRCLE AND ITALY: William Clarke and the Roscoe Circle, Arline Wilson; Un amico del Roscoe: William Shepherd and the first modern Life of Poggio Bracciolini (1802), David Rundle; William Roscoe and Thomas Coke of Holkham, Andrea M. Gáldy. PART IV WIDER DISSEMINATION: Roscoe’s Renaissance in America, Melissa Meriam Bullard; Index.