'Touch the Truth'?: Desiderio Da Settignano, Renaissance Relief And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Paintings and Sculpture Given to the Nation by Mr. Kress and Mr

e. FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE THE COLLECTIONS OF THE NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART \YASHINGTON The National Gallery will open to the public on March 18, 1941. For the first time, the Mellon Collection, deeded to the Nation in 1937, and the Kress Collection, given in 1939, will be shown. Both collections are devoted exclusively to painting and sculpture. The Mellon Collection covers the principal European schools from about the year 1200 to the early XIX Century, and includes also a number of early American portraits. The Kress Collection exhibits only Italian painting and sculpture and illustrates the complete development of the Italian schools from the early XIII Century in Florence, Siena, and Rome to the last creative moment in Venice at the end of the XVIII Century. V.'hile these two great collections will occupy a large number of galleries, ample space has been left for future development. Mr. Joseph E. Videner has recently announced that the Videner Collection is destined for the National Gallery and it is expected that other gifts will soon be added to the National Collection. Even at the present time, the collections in scope and quality will make the National Gallery one of the richest treasure houses of art in the wor 1 d. The paintings and sculpture given to the Nation by Mr. Kress and Mr. Mellon have been acquired from some of -2- the most famous private collections abroad; the Dreyfus Collection in Paris, the Barberini Collection in Rome, the Benson Collection in London, the Giovanelli Collection in Venice, to mention only a few. -

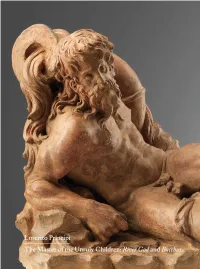

The Master of the Unruly Children and His Artistic and Creative Identities

The Master of the Unruly Children and his Artistic and Creative Identities Hannah R. Higham A Thesis Submitted to The University of Birmingham For The Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Art History, Film and Visual Studies School of Languages, Art History and Music College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham May 2015 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis examines a group of terracotta sculptures attributed to an artist known as the Master of the Unruly Children. The name of this artist was coined by Wilhelm von Bode, on the occasion of his first grouping seven works featuring animated infants in Berlin and London in 1890. Due to the distinctive characteristics of his work, this personality has become a mainstay of scholarship in Renaissance sculpture which has focused on identifying the anonymous artist, despite the physical evidence which suggests the involvement of several hands. Chapter One will examine the historiography in connoisseurship from the late nineteenth century to the present and will explore the idea of the scholarly “construction” of artistic identity and issues of value and innovation that are bound up with the attribution of these works. -

Press Release

NEWS FROM THE GETTY news.getty.edu | [email protected] DATE: March 23, 2018 MEDIA CONTACT: FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Amy Hood Getty Communications (310)440-6427 [email protected] GETTY MUSEUM ACQUIRES BUST OF A YOUNG BOY, BY DESIDERIO DA SETTIGNANO, ABOUT 1460–64 The endearing marble sculpture is a rare masterpiece by one of the most skilled and influential sculptors of Renaissance Florence Bust of a Young Boy, about 1460–1464, Desiderio da Settignano (about 1430 – 1464), marble. 25 x 24.5 x 14 cm (9 13/16 x 9 5/8 x 5 1/2 in.) The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles LOS ANGELES – The Getty Museum has acquired Bust of a Young Boy, about 1460-64, by Desiderio de Settignano (Italian, circa 1430–1464). The approximately life-size sculpture is a well-known work by one of the most influential and skilled sculptors in Quattrocento (fifteenth-century) Florence. “This is an extraordinarily fine work by one of the greatest sculptors of the early Renaissance,” said Timothy Potts, director of the Getty Museum. “In his short but spectacular career (he died at about age 34), Desiderio de Settignano became one of the most renowned The J. Paul Getty Trust 1200 Getty center Drive, Suite 403 Tel: 310 440 7360 www.getty.edu Communications Department Los Angeles, CA 90049-1681 Fax 310 440 7722 and sought-after artists of his generation, and it is remarkable good fortune that we are able to add such a rare and iconic work of his to our collection. Although sculptures dating from Quattrocento Florence have for museums been among the most coveted trophies for over a century, there is nothing comparable to this bust in any West Coast museum. -

Terracotta Tableau Sculpture in Italy, 1450-1530

PALPABLE POLITICS AND EMBODIED PASSIONS: TERRACOTTA TABLEAU SCULPTURE IN ITALY, 1450-1530 by Betsy Bennett Purvis A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy Department of Art University of Toronto ©Copyright by Betsy Bennett Purvis 2012 Palpable Politics and Embodied Passions: Terracotta Tableau Sculpture in Italy, 1450-1530 Doctorate of Philosophy 2012 Betsy Bennett Purvis Department of Art University of Toronto ABSTRACT Polychrome terracotta tableau sculpture is one of the most unique genres of 15th- century Italian Renaissance sculpture. In particular, Lamentation tableaux by Niccolò dell’Arca and Guido Mazzoni, with their intense sense of realism and expressive pathos, are among the most potent representatives of the Renaissance fascination with life-like imagery and its use as a powerful means of conveying psychologically and emotionally moving narratives. This dissertation examines the versatility of terracotta within the artistic economy of Italian Renaissance sculpture as well as its distinct mimetic qualities and expressive capacities. It casts new light on the historical conditions surrounding the development of the Lamentation tableau and repositions this particular genre of sculpture as a significant form of figurative sculpture, rather than simply an artifact of popular culture. In terms of historical context, this dissertation explores overlooked links between the theme of the Lamentation, the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem, codes of chivalric honor and piety, and resurgent crusade rhetoric spurred by the fall of Constantinople in 1453. Reconnected to its religious and political history rooted in medieval forms of Sepulchre devotion, the terracotta Lamentation tableau emerges as a key monument that both ii reflected and directed the cultural and political tensions surrounding East-West relations in later 15th-century Italy. -

The Commissioning of Artwork for Charterhouses During the Middle Ages

Geography and circulation of artistic models The Commissioning of Artwork for Charterhouses during the Middle Ages Cristina DAGALITA ABSTRACT In 1084, Bruno of Cologne established the Grande Chartreuse in the Alps, a monastery promoting hermitic solitude. Other charterhouses were founded beginning in the twelfth century. Over time, this community distinguished itself through the ideal purity of its contemplative life. Kings, princes, bishops, and popes built charterhouses in a number of European countries. As a result, and in contradiction with their initial calling, Carthusians drew closer to cities and began to welcome within their monasteries many works of art, which present similarities that constitute the identity of Carthusians across borders. Jean de Marville and Claus Sluter, Portal of the Chartreuse de Champmol monastery church, 1386-1401 The founding of the Grande Chartreuse in 1084 near Grenoble took place within a context of monastic reform, marked by a return to more strict observance. Bruno, a former teacher at the cathedral school of Reims, instilled a new way of life there, which was original in that it tempered hermitic existence with moments of collective celebration. Monks lived there in silence, withdrawn in cells arranged around a large cloister. A second, smaller cloister connected conventual buildings, the church, refectory, and chapter room. In the early twelfth century, many communities of monks asked to follow the customs of the Carthusians, and a monastic order was established in 1155. The Carthusians, whose calling is to devote themselves to contemplative exercises based on reading, meditation, and prayer, in an effort to draw as close to the divine world as possible, quickly aroused the interest of monarchs. -

The Master of the Unruly Children: River God and Bacchus TRINITY

TRINITY FINE ART Lorenzo Principi The Master of the Unruly Children: River God and Bacchus London February 2020 Contents Acknowledgements: Giorgio Bacovich, Monica Bassanello, Jens Burk, Sara Cavatorti, Alessandro Cesati, Antonella Ciacci, 1. Florence 1523 Maichol Clemente, Francesco Colaucci, Lavinia Costanzo , p. 12 Claudia Cremonini, Alan Phipps Darr, Douglas DeFors , 2. Sandro di Lorenzo Luizetta Falyushina, Davide Gambino, Giancarlo Gentilini, and The Master of the Unruly Children Francesca Girelli, Cathryn Goodwin, Simone Guerriero, p. 20 Volker Krahn, Pavla Langer, Guido Linke, Stuart Lochhead, Mauro Magliani, Philippe Malgouyres, 3. Ligefiguren . From the Antique Judith Mann, Peta Motture, Stefano Musso, to the Master of the Unruly Children Omero Nardini, Maureen O’Brien, Chiara Padelletti, p. 41 Barbara Piovan, Cornelia Posch, Davide Ravaioli, 4. “ Bene formato et bene colorito ad imitatione di vero bronzo ”. Betsy J. Rosasco, Valentina Rossi, Oliva Rucellai, The function and the position of the statuettes of River God and Bacchus Katharina Siefert, Miriam Sz ó´cs, Ruth Taylor, Nicolas Tini Brunozzi, Alexandra Toscano, Riccardo Todesco, in the history of Italian Renaissance Kleinplastik Zsófia Vargyas, Laëtitia Villaume p. 48 5. The River God and the Bacchus in the history and criticism of 16 th century Italian Renaissance sculpture Catalogue edited by: p. 53 Dimitrios Zikos The Master of the Unruly Children: A list of the statuettes of River God and Bacchus Editorial coordination: p. 68 Ferdinando Corberi The Master of the Unruly Children: A Catalogue raisonné p. 76 Bibliography Carlo Orsi p. 84 THE MASTER OF THE UNRULY CHILDREN probably Sandro di Lorenzo di Smeraldo (Florence 1483 – c. 1554) River God terracotta, 26 x 33 x 21 cm PROVENANCE : heirs of the Zalum family, Florence (probably Villa Gamberaia) THE MASTER OF THE UNRULY CHILDREN probably Sandro di Lorenzo di Smeraldo (Florence 1483 – c. -

Johan Maelwael

Johan Maelwael 34 l COLLECT Een Nijmegenaar in Bourgondië In 2005 werd in Museum Valkhof de vroege Nederlandse schilderkunst geëerd met linkerpagina Johan Maelwael & Henry Bellechose, een tentoonstelling over de gebroeders Van Limburg. De meest meeslepende anek- ‘Madonna met Kind engelen en vlinders’, Dijon, ca.1415, Berlijn, Ge- dote over hen is dat twee van de drie broers in november 1399 door Brabantse mi- mäldegalerie. litanten werden gegijzeld in Brussel. De tieners werden na een gevangenschap van meer dan een half jaar vrijgelaten omdat Filips de Stoute, de hertog van Bourgondië, het losgeld voor de jongens betaalde. Dit deed hij omdat hun oom zeer verdienstelijk werk voor hem had verricht en dat in de toekomst zou blijven doen. Deze geprezen oom was Johan Maelwael (ca. 1370-1415). Dit najaar organiseert het Rijksmuseum de eerste tentoonstelling die draait om deze schilder. TEKST: JOCHEM VAN EIJSDEN aelwael werd geboren rond 1370 in Nij- megen als telg van een van de meest Als leider van het atelier hoefde Maelwael zich niet Mvermaarde schildersfamilies in de Noor- delijke Nederlanden. De familienaam is in het alleen bezig te houden met de daadwerkelijke uitvoering Middelnederlands een blijk van waardering voor hun professionele kunde: ‘hij die goed schildert’, van de kunstobjecten in het kartuizerklooster. een uiting die ook werd onderschreven door het hertogelijke hof van Gelre. Nadat vader Willem Maelwael en oom Herman schilderwerk voor de Zo inspecteerde hij samen met zijn beeldhouwende stad Nijmegen hadden uitgevoerd, werkten zij van Hollandse evenknie Claus Sluter ook de stukken 1386 tot 1397 een behoorlijk aantal keer voor de die door andere kunstenaars werden aangeleverd, hertog van Gelre. -

Questa Speciale Pubblicazione Permette Di Seguire Un Itinerario Tra Luoghi Di Firenze E Della Toscana Per Celebrare Una Stagione Unica Per La Storia Dell’Arte

Questa speciale pubblicazione permette di seguire un itinerario tra luoghi di Firenze e della Toscana per celebrare una stagione unica per la storia dell’arte. This special booklet is designed to offer you an Con Verrocchio, il maestro itinerary embracing sites di Leonardo, Palazzo in Florence and Tuscany, Strozzi celebra Andrea del to celebrate a truly unique Verrocchio, artista simbolo del season in the history of art. Rinascimento, attraverso una grande mostra che ospita oltre With Verrocchio, Master of 120 opere tra dipinti, sculture Leonardo, Palazzo Strozzi e disegni provenienti dai più celebrates Andrea del importanti musei e collezioni Verrocchio, an emblematic artist del mondo. L’esposizione, of the Florentine Renaissance, con una sezione speciale al in a major exhibition showcasing Museo Nazionale del Bargello, over 120 paintings, sculptures raccoglie insieme per la prima and drawings from the volta celebri capolavori di world’s leading museums and Verrocchio e opere capitali dei collections. The exhibition, più famosi artisti della seconda with a special section at the metà del Quattrocento Museo Nazionale del Bargello, legati alla sua bottega, come brings together for the first time Domenico del Ghirlandaio, both Verrocchio’s celebrated Sandro Botticelli, Pietro masterpieces and capital works Perugino e Leonardo da Vinci, by the best-known artists il suo più famoso allievo, di associated with his workshop in cui sarà possibile ricostruire la the second half of the 15th century formazione e lo scambio con il such as Domenico Ghirlandaio, maestro attraverso eccezionali Sandro Botticelli, Pietro Perugino prestiti e inediti confronti. and Leonardo da Vinci, his most famous pupil, reconstructing Leonardo’s early artistic career and interaction with his master thanks to outstanding loans and unprecedented juxtapositions. -

14 CH14 P468-503.Qxp 9/10/09 11:40 Page 468 14 CH14 P468-503.Qxp 9/10/09 11:40 Page 469 CHAPTER 14 Artistic Innovations in Fifteenth-Century Northern Europe

14_CH14_P468-503.qxp 9/10/09 11:40 Page 468 14_CH14_P468-503.qxp 9/10/09 11:40 Page 469 CHAPTER 14 Artistic Innovations in Fifteenth-Century Northern Europe HE GREAT CATHEDRALS OF EUROPE’S GOTHIC ERA—THE PRODUCTS of collaboration among church officials, rulers, and the laity—were mostly completed by 1400. As monuments of Christian faith, they T exemplify the medieval outlook. But cathedrals are also monuments of cities, where major social and economic changes would set the stage for the modern world. As the fourteenth century came to an end, the were emboldened to seek more autonomy from the traditional medieval agrarian economy was giving way to an economy based aristocracy, who sought to maintain the feudal status quo. on manufacturing and trade, activities that took place in urban Two of the most far-reaching changes concerned increased centers. A social shift accompanied this economic change. Many literacy and changes in religious expression. In the fourteenth city dwellers belonged to the middle classes, whose upper ranks century, the pope left Rome for Avignon, France, where his enjoyed literacy, leisure, and disposable income. With these successors resided until 1378. On the papacy’s return to Rome, advantages, the middle classes gained greater social and cultural however, a faction remained in France and elected their own pope. influence than they had wielded in the Middle Ages, when the This created a schism in the Church that only ended in 1417. But clergy and aristocracy had dominated. This transformation had a the damage to the integrity of the papacy had already been done. -

Michelangelo Buonarotti

MICHELANGELO BUONAROTTI Portrait of Michelangelo by Daniele da Volterra COMPILED BY HOWIE BAUM Portrait of Michelangelo at the time when he was painting the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. by Marcello Venusti Hi, my name is Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni, but you can call me Michelangelo for short. MICHAELANGO’S BIRTH AND YOUTH Michelangelo was born to Leonardo di Buonarrota and Francesca di Neri del Miniato di Siena, a middle- class family of bankers in the small village of Caprese, in Tuscany, Italy. He was the 2nd of five brothers. For several generations, his Father’s family had been small-scale bankers in Florence, Italy but the bank failed, and his father, Ludovico di Leonardo Buonarroti Simoni, briefly took a government post in Caprese. Michelangelo was born in this beautiful stone home, in March 6,1475 (546 years ago) and it is now a museum about him. Once Michelangelo became famous because of his beautiful sculptures, paintings, and poetry, the town of Caprese was named Caprese Michelangelo, which it is still named today. HIS GROWING UP YEARS BETWEEN 6 AND 13 His mother's unfortunate and prolonged illness forced his father to place his son in the care of his nanny. The nanny's husband was a stonecutter, working in his own father's marble quarry. In 1481, when Michelangelo was six years old, his mother died yet he continued to live with the pair until he was 13 years old. As a child, he was always surrounded by chisels and stone. He joked that this was why he loved to sculpt in marble. -

PDF Hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen

PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/105227 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2017-12-06 and may be subject to change. M e d ia e v a l p a in t in g in t h e N e t h e r l a n d s In the first decade of the fifteenth century, somewhere in the South Netherlands, the Apocalypse (Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, néerlandais 3) was written in Dutch (dietsche) and illuminated. No- one knows with any certainty exactly where this happened. Erwin Panofsky in his famous Early Netherlan dish Painting (1953) argued convincingly for Liège,· later Maurits Smeyers (1993) claimed it for Bruges (and did so again in his standard work Vlaamse Miniaturen (1998)). The manuscript cannot possibly have been written and illuminated in Liège, nor is it certain that it comes from Bruges (as convincingly demonstrat ed by De Hommel-Steenbakkers, 2001 ). Based on a detailed analysis of the language and traces of dialect in the Dutch text of the Apocalypse, Nelly de Hommel-Steenbakkers concluded that the manuscript originated in Flanders, or perhaps in Brabant. It might well have come from Bruges though, a flourishing town in the field of commerce and culture, but other places, such as Ghent, Ypres, Tournai and maybe Brussels, cannot be ruled out,· other possible candidates are the intellectual and cultural centres in the larger abbeys. -

Donatello, Michelangelo, and Bernini: Their

DONATELLO, MICHELANGELO, AND BERNINI: THEIR UNDERSTANDING OF ANTIQUITY AND ITS INFLUENCE ON THE REPRESENTATION OF DAVID by Kathryn Sanders Department of Art and Art History April 7, 2020 A thesis submitted to the Honors Council of the University of the Colorado Dr. Robert Nauman honors council representative, department of Art and Art History Dr. Fernando Loffredo thesis advisor, department of Art and Art History Dr. Sarah James committee member, department of Classics TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………..……………….……………1 Chapter I: The Davids…………………………………………………..…………………5 Chapter II: Antiquity and David…………………………………………………………21 CONCLUSION………………...………………………………………………………………...40 BIBLIOGRAPHY………………………………………………………………………………..58 LIST OF FIGURES Figure 1: Donatello, David, 1430s……………………………………………………………….43 Figure 2: Michelangelo, David, 1504……………………………………………………………44 Figure 3: Bernini, David, 1624…………………………………………………………………..45 Figure 4: Donatello, David, 1408-1409………………………………………………………….46 Figure 5: Taddeo Gaddi, David, 1330…………………………………………………………...47 Figure 6: Donatello, Saint Mark, 1411…………………………………………………………..48 Figure 7: Andrea del Verrocchio, David, 1473-1475……………………………………………49 Figure 8: Bernini, Monsignor Montoya, 1621-1622……………………………………………..50 Figure 9: Bernini, Damned Soul, 1619…………………………………………………………..51 Figure 10: Annibale Carracci, Polyphemus and Acis, 1595-1605……………………………….52 Figure 11: Anavysos Kouros, 530 BCE………………………………………………………….53 Figure 12: Polykleitos, Doryphoros, 450-440 BCE……………………………………………..54 Figure 13: Praxiteles, Hermes and Dionysus, 350-330 BCE…………………………………….55 Figure 14: Myron, Discobolus, 460-450 BCE…………………………………………………...56 Figure 15: Agasias, Borghese Gladiator, 101 BCE……………………………………………...57 Introduction “And there came out from the camp of the Philistines a champion named Goliath, of Gath, whose height was six cubits and a span. He had a helmet of bronze on his head, and he was armed with a coat of mail; the weight of the coat was five thousand shekels of bronze.