___1 Giorgio Vasari, Cosimo I De ̓ Medici with His Architects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Master of the Unruly Children and His Artistic and Creative Identities

The Master of the Unruly Children and his Artistic and Creative Identities Hannah R. Higham A Thesis Submitted to The University of Birmingham For The Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Art History, Film and Visual Studies School of Languages, Art History and Music College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham May 2015 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis examines a group of terracotta sculptures attributed to an artist known as the Master of the Unruly Children. The name of this artist was coined by Wilhelm von Bode, on the occasion of his first grouping seven works featuring animated infants in Berlin and London in 1890. Due to the distinctive characteristics of his work, this personality has become a mainstay of scholarship in Renaissance sculpture which has focused on identifying the anonymous artist, despite the physical evidence which suggests the involvement of several hands. Chapter One will examine the historiography in connoisseurship from the late nineteenth century to the present and will explore the idea of the scholarly “construction” of artistic identity and issues of value and innovation that are bound up with the attribution of these works. -

Elenco Manoscritti

Elenco Manoscritti Bibl. Nazionale 1 FRONTINI.= De Re Militari in cambio del 259 2 Ricordanze di Neri di Bicci dipintore, da Biblioteca 1453-1475 Strozzi 3 ADRIANO Marcello Juniore = De Categoria 4 S.S. PATRUM = Opuscolo D. Augusti et Bibl. Nazionale Hyaronimi. Come sopra 5 VACCA FLAMINIO = Antichità di Roma da Biblioteca Strozzi 6 Epitaffio et elogia (Cod. Cartaceo del sec. XVI) 7 Inscriptiones Romanae (2 voll.) da Biblioteca Strozzi 8 Trattato sopra i nomi dalle Tribù da Biblioteca Strozzi 9 BOCCHI = Sulle opere di Andrea del Sarto da Biblioteca Strozzi (Borghini invenzione della cupola) 10 VASARI = Alcuni disegni di macchine, da Biblioteca Statuti della Accademia del Strozzi Disegno...(1584) 11 Ragionamento con Francesco de' Medici da Biblioteca Strozzi sopra le pitture di Palazzo Vecchio.... (Del Vasari) 12 STROZZI = Iscrizioni antiche da Biblioteca Strozzi ? 13 NORIS = Epistolae e studi diversi (Cod. del XVII sec.) 14 Medaglie d'oro della serie Imperiale. 15 Tavole di pittura e sculture egregio. 16 PANETALIO, P. = Trattato della pittura del Lomazzo. da Biblioteca Strozzi 17 MIRABELLA = Medaglie consolari. da Biblioteca 18 Erudizione orientale di numismatica. Strozzi 19 BACINI lasciati per legato alla Casa Medici.... 20 BIANCHI = Descrizione dalla R. Galleria 21 BIANCHI = Catalogo della Imperial Galleria di Firenze. 22 COCCHI = Studi diversi di antiquaria. 23 " = Notizie sopra alcune medaglie 24 " = Indice di Medaglie per classi (5 filze) 25 PELLI BENCIVENNI = Notizie della R. Galleria 26 Studi degli antiquari Bassetti, Querci e Pelli. 27 LANZI = Miscellanea (4 volumi) 28 LANZI = Repertorivm earum ..Inscriptiones pert.. 29 LANZI = Repertorio di Medaglie consolari... 30 LANZI = Repertorium de caracteribus 31 LANZI = Repertorio di antichità figurate. -

Coexistence of Mythological and Historical Elements

COEXISTENCE OF MYTHOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL ELEMENTS AND NARRATIVES: ART AT THE COURT OF THE MEDICI DUKES 1537-1609 Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................ 3 Greek and Roman examples of coexisting themes ........................................................................ 6 1. Cosimo’s Triumphal Propaganda ..................................................................................................... 7 Franco’s Battle of Montemurlo and the Rape of Ganymede ........................................................ 8 Horatius Cocles Defending the Pons Subicius ................................................................................. 10 The Sacrificial Death of Marcus Curtius ........................................................................................... 13 2. Francesco’s parallel narratives in a personal space .............................................................. 16 The Studiolo ................................................................................................................................................ 16 Marsilli’s Race of Atalanta ..................................................................................................................... 18 Traballesi’s Danae .................................................................................................................................... 21 3. Ferdinando’s mythological dream ............................................................................................... -

The Flowering of Florence: Botanical Art for the Medici" on View at the National Gallery of Art March 3 - May 27, 2002

Office of Press and Public Information Fourth Street and Constitution Av enue NW Washington, DC Phone: 202-842-6353 Fax: 202-789-3044 www.nga.gov/press Release Date: February 26, 2002 Passion for Art and Science Merge in "The Flowering of Florence: Botanical Art for the Medici" on View at the National Gallery of Art March 3 - May 27, 2002 Washington, DC -- The Medici family's passion for the arts and fascination with the natural sciences, from the 15th century to the end of the dynasty in the 18th century, is beautifully illustrated in The Flowering of Florence: Botanical Art for the Medici, at the National Gallery of Art's East Building, March 3 through May 27, 2002. Sixty-eight exquisite examples of botanical art, many never before shown in the United States, include paintings, works on vellum and paper, pietre dure (mosaics of semiprecious stones), manuscripts, printed books, and sumptuous textiles. The exhibition focuses on the work of three remarkable artists in Florence who dedicated themselves to depicting nature--Jacopo Ligozzi (1547-1626), Giovanna Garzoni (1600-1670), and Bartolomeo Bimbi (1648-1729). "The masterly technique of these remarkable artists, combined with freshness and originality of style, has had a lasting influence on the art of naturalistic painting," said Earl A. Powell III, director, National Gallery of Art. "We are indebted to the institutions and collectors, most based in Italy, who generously lent works of art to the exhibition." The Exhibition Early Nature Studies: The exhibition begins with an introductory section on nature studies from the late 1400s and early 1500s. -

Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Sassetta's Madonna della Neve. An Image of Patronage Israëls, M. Publication date 2003 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Israëls, M. (2003). Sassetta's Madonna della Neve. An Image of Patronage. Primavera Pers. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:03 Oct 2021 Index Note Page references in bold indicate Avignonese period of the papacy, 108, Bernardino, Saint, 26, 82n, 105 illustrations. 11 in Bertini (family), 3on, 222 - Andrea di Francesco, 19, 21, 30 Abbadia Isola Baccellieri, Baldassare, 15011 - Ascanio, 222 - Abbey of Santi Salvatore e Cirino, Badia Bcrardcnga, 36n - Beatrice di Ascanio, 222, 223 -

Indipendenza

ItinerariItinerari PIAZZE FFIRENZEIRENZE e 17th may 2009 nell’nell’800 MUSICA Piazza dell’Indipendenza The 19th Century Florence itineraries: Squares and Music ThTTheh brass band of the Scuola Marescialli e Brigadieri deddeie Carabinieri is one of the fi ve Carabinieri bands whwwhoseh origin lies in the buglers of the various Legions TheTh 19th19th CenturyC t FlorenceFl ititinerariesi i – 17th1717 h may 2009200009 of the Carabinieri, from which the fi rst bands were designed signifi cantly to coincide with Piazza later formed with brass and percussion instruments. the150th anniversary of the unifi cation of dell’Indipendenza, Today the Brass Band – based in Florence at the Tuscany to the newly born unifi ed state (1859 11.00 am-12.30 am School with the same name – is a small band with – 2009) – will take citizens and tourists on the a varied repertoire (symphonies, operas, fi lm sound discovery of the traces of a Century that left a Fanfara (Brass tracks as well as blues and jazz), especially trained for profound impression on the face of Florence. band) of the its main activity: the performance of ceremonies with The idea is to restore the role of 19th Century Scuola Marescialli assemblies and marches typical of military music. The band wears the so-called Grande Uniforme Speciale, a Florence within the collective imagination, e Brigadieri alongside the Florence of Medieval and very special uniform with its typical hat known as the Renaissance times. This is why one of the dell’Arma dei “lucerna” (cocked hat) and the red and white plume Carabinieri that sets it apart from the musicians of other units of Century’s typical customs will be renewed: the Carabinieri (red-blue plume). -

Reviews Summer 2020

$UFKLWHFWXUDO Marinazzo, A, et al. 2020. Reviews Summer 2020. Architectural Histories, 8(1): 11, pp. 1–13. DOI: +LVWRULHV https://doi.org/10.5334/ah.525 REVIEW Reviews Summer 2020 Adriano Marinazzo, Stefaan Vervoort, Matthew Allen, Gregorio Astengo and Julia Smyth-Pinney Marinazzo, A. A Review of William E. Wallace, Michelangelo, God’s Architect: The Story of His Final Years and Greatest Masterpiece. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2019. Vervoort, S. A Review of Matthew Mindrup, The Architectural Model: Histories of the Miniature and the Prototype, the Exemplar and the Muse. Cambridge, MA, and London: The MIT Press, 2019. Allen, M. A Review of Joseph Bedford, ed., Is There an Object-Oriented Architecture? Engaging Graham Harman. London and New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2020. Astengo, G. A Review of Vaughan Hart, Christopher Wren: In Search of Eastern Antiquity. London: Yale University Press, 2020. Smyth-Pinney, J. A Review of Maria Beltramini and Cristina Conti, eds., Antonio da Sangallo il Giovane: Architettura e decorazione da Leone X a Paolo III. Milan: Officina libraria, 2018. Becoming the Architect of St. Peter’s: production of painting, sculpture and architecture and Michelangelo as a Designer, Builder and his ‘genius as entrepreneur’ (Wallace 1994). With this new Entrepreneur research, in his eighth book on the artist, Wallace mas- terfully synthesizes what aging meant for a genius like Adriano Marinazzo Michelangelo, shedding light on his incredible ability, Muscarelle Museum of Art at William and Mary, US despite (or thanks to) his old age, to deal with an intri- [email protected] cate web of relationships, intrigues, power struggles and monumental egos. -

Inventario (1

INVENTARIO (1 - 200) 1 Scatola contenente tre fascicoli. V. segn. 1 ELETTRICE PALATINA ANNA MARIA LUISA DE’ MEDICI 1 Lettere di auguri natalizi all’elettrice palatina Anna Maria Luisa de’ Medici di: Filippo Acciaiuoli, cc.2-4; Faustina Acciaiuoli Bolognetti, cc.5-7; Isabella Acquaviva Strozzi, cc.8-10; cardinale Alessandro Albani, cc.11-13; Fi- lippo Aldrovandi Marescotti, cc.14-16; Maria Vittoria Altoviti Cor- sini, cc.17-19; Achille Angelelli, cc.20-23; Roberto Angelelli, cc.24- 26; Dorothea Angelelli Metternich, cc.27-29; Lucrezia Ansaldi Le- gnani, cc.30-32; Giovanni dell’Aquila, cc.33-35; duchessa Douariere d’Arenberg, con responsiva, cc.36-40; governatore di Grosseto Cosimo Bagnesi, cc.41-43; Andrea Barbazzi, cc.44-46; segretario della Sacra Consulta Girolamo de’ Bardi, cc.47-49; cardinale [Lodovico] Belluga, cc.50-52; Lucrezia Bentivoglio Dardinelli, cc.53-55; Maria Bergonzi Ra- nuzzi, cc.56-58; cardinale Vincenzo Bichi, cc.59-61; «re delle Due Si- Nell’inventario, il numero del pezzo è posto al centro in neretto. Alla riga successiva, in cor- cilie» Carlo VII, con responsiva, cc.62-66; vescovo di Borgo Sansepol- sivo, sono riportate la descrizione estrinseca del volume, registro o busta con il numero com- cro [Raimondo Pecchioli], cc.67-69; Camilla Borgogelli Feretti, cc.70- plessivo dei fascicoli interni e le vecchie segnature. Quando il nesso contenutistico fra i do- 72; Cosimo Bourbon del Monte, cc.73-75; baronessa de Bourscheidt, cumenti lo rendeva possibile si è dato un titolo generale - in maiuscoletto - a tutto il pezzo, con responsiva, cc.76-79; vescovo di Cagli [Gerolamo Maria Allegri], o si è trascritto, tra virgolette in maiuscoletto, il titolo originale. -

Terracotta Tableau Sculpture in Italy, 1450-1530

PALPABLE POLITICS AND EMBODIED PASSIONS: TERRACOTTA TABLEAU SCULPTURE IN ITALY, 1450-1530 by Betsy Bennett Purvis A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy Department of Art University of Toronto ©Copyright by Betsy Bennett Purvis 2012 Palpable Politics and Embodied Passions: Terracotta Tableau Sculpture in Italy, 1450-1530 Doctorate of Philosophy 2012 Betsy Bennett Purvis Department of Art University of Toronto ABSTRACT Polychrome terracotta tableau sculpture is one of the most unique genres of 15th- century Italian Renaissance sculpture. In particular, Lamentation tableaux by Niccolò dell’Arca and Guido Mazzoni, with their intense sense of realism and expressive pathos, are among the most potent representatives of the Renaissance fascination with life-like imagery and its use as a powerful means of conveying psychologically and emotionally moving narratives. This dissertation examines the versatility of terracotta within the artistic economy of Italian Renaissance sculpture as well as its distinct mimetic qualities and expressive capacities. It casts new light on the historical conditions surrounding the development of the Lamentation tableau and repositions this particular genre of sculpture as a significant form of figurative sculpture, rather than simply an artifact of popular culture. In terms of historical context, this dissertation explores overlooked links between the theme of the Lamentation, the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem, codes of chivalric honor and piety, and resurgent crusade rhetoric spurred by the fall of Constantinople in 1453. Reconnected to its religious and political history rooted in medieval forms of Sepulchre devotion, the terracotta Lamentation tableau emerges as a key monument that both ii reflected and directed the cultural and political tensions surrounding East-West relations in later 15th-century Italy. -

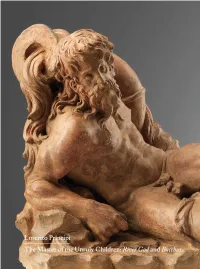

The Master of the Unruly Children: River God and Bacchus TRINITY

TRINITY FINE ART Lorenzo Principi The Master of the Unruly Children: River God and Bacchus London February 2020 Contents Acknowledgements: Giorgio Bacovich, Monica Bassanello, Jens Burk, Sara Cavatorti, Alessandro Cesati, Antonella Ciacci, 1. Florence 1523 Maichol Clemente, Francesco Colaucci, Lavinia Costanzo , p. 12 Claudia Cremonini, Alan Phipps Darr, Douglas DeFors , 2. Sandro di Lorenzo Luizetta Falyushina, Davide Gambino, Giancarlo Gentilini, and The Master of the Unruly Children Francesca Girelli, Cathryn Goodwin, Simone Guerriero, p. 20 Volker Krahn, Pavla Langer, Guido Linke, Stuart Lochhead, Mauro Magliani, Philippe Malgouyres, 3. Ligefiguren . From the Antique Judith Mann, Peta Motture, Stefano Musso, to the Master of the Unruly Children Omero Nardini, Maureen O’Brien, Chiara Padelletti, p. 41 Barbara Piovan, Cornelia Posch, Davide Ravaioli, 4. “ Bene formato et bene colorito ad imitatione di vero bronzo ”. Betsy J. Rosasco, Valentina Rossi, Oliva Rucellai, The function and the position of the statuettes of River God and Bacchus Katharina Siefert, Miriam Sz ó´cs, Ruth Taylor, Nicolas Tini Brunozzi, Alexandra Toscano, Riccardo Todesco, in the history of Italian Renaissance Kleinplastik Zsófia Vargyas, Laëtitia Villaume p. 48 5. The River God and the Bacchus in the history and criticism of 16 th century Italian Renaissance sculpture Catalogue edited by: p. 53 Dimitrios Zikos The Master of the Unruly Children: A list of the statuettes of River God and Bacchus Editorial coordination: p. 68 Ferdinando Corberi The Master of the Unruly Children: A Catalogue raisonné p. 76 Bibliography Carlo Orsi p. 84 THE MASTER OF THE UNRULY CHILDREN probably Sandro di Lorenzo di Smeraldo (Florence 1483 – c. 1554) River God terracotta, 26 x 33 x 21 cm PROVENANCE : heirs of the Zalum family, Florence (probably Villa Gamberaia) THE MASTER OF THE UNRULY CHILDREN probably Sandro di Lorenzo di Smeraldo (Florence 1483 – c. -

Construction As Depicted in Western Art Construction As Depicted in Western Art

Tutton Construction Michael Tutton as Depicted in Western Art Construction as Depicted in Western Art Western in Depicted as Construction From Antiquity to the Photograph Construction as Depicted in Western Art Construction as Depicted in Western Art From Antiquity to the Photograph Michael Tutton Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: 1587, German, unknown master, The Tower of Babel, oil or tempera on panel. Z 2249, Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg. Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6298 255 0 e-isbn 978 90 4853 259 9 doi 10.5117/9789462982550 nur 684 © M. Tutton / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2021 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. Every effort has been made to obtain permission to use all copyrighted illustrations reproduced in this book. Nonetheless, whosoever believes to have rights to this material is advised to contact the publisher. For Catherine, Emma and Samuel Acknowledgements I wish to acknowledge the following for help and support in producing this book: Catherine Tutton, Emma Tutton, Nicole Blondin, James W P Campbell, David Davidson, Monica Knight, Eleonora Scianna, Catherine Yvard, and my editors at AUP. Table of Contents Acknowledgements 7 List of Figures 11 Introduction 31 Scope 31 Current Literature and Sources 32 Definitions 33 Layout of the Book 33 1. -

Ocnus: an Allegory of the Futility of Labour Pen and Brown Ink and Wash, Heightened with White, Over an Underdrawing in Black Chalk, on Blue Paper

Jacopo LIGOZZI (Vérone 1547 - Florence 1632) Ocnus: An Allegory of the Futility of Labour Pen and brown ink and wash, heightened with white, over an underdrawing in black chalk, on blue paper. The outlines of the main figure indented for transfer and the verso washed red. Inscribed Giorgio Vasari [cancelled] at the lower right. 200 x 151 mm. (7 7/8 x 6 in.) In its use of blue paper and its stylistic relationship with late 16th century Veronese and Venetian draughtsmanship, the present sheet may tentatively be dated to the early part of Jacopo Ligozzi’s career, while he was working in Verona or shortly after his arrival in Florence in 1577. Jennifer Montagu has pointed out that the unusual subject of this drawing derives from an ancient Greek painting by Polygnotus of the mythological character of Ocnus (or Oknos); a figure symbolic of futility, or unending labour. Ocnus was condemned to spend eternity weaving a rope of straw which, in turn, was eaten by a donkey almost as fast as it is made. As Montagu notes, Ocnus ‘had an extravagant wife who spent everything he earned by his labours; he is represented as a man twisting a cord, which an ass standing by eats as soon as he makes it, whence the proverb ‘the cord of Ocnus’ often applied to a labour which meets no return, and is totally lost.’ This unusual subject is extremely rare in 16th or 17th century Italian art. Many of Ligozzi’s highly finished drawings were executed as independent works of art, and this may be true of the present sheet.