UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Craters in Shadow

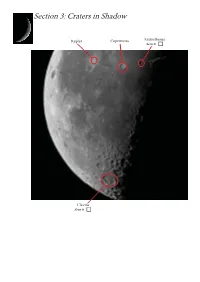

Section 3: Craters in Shadow Kepler Copernicus Eratosthenes Seen it Clavius Seen it Section 3: Craters in Shadow Visibility: A pair of binoculars is the minimum requirement to see these features. When: Look for them when the terminator’s close by, typically a day before last quarter. Not all craters are best seen when the Sun is high in the lunar sky - in fact most aren’t! If craters aren’t par- ticularly bright or dark, they tend to disappear into the background when the Moon’s phase is close to full. These craters are best seen when the ‘terminator’ is nearby, or when the Sun is low in the lunar sky as seen from the crater. This causes oblique lighting to fall on the crater and create exaggerated shadows. Ultimately, this makes the crater look more dramatic and easier to see. We’ll use this effect for the next section on lunar mountains, but before we do, there are a couple of craters that we’d like to bring to your attention. Actually, the Moon is covered with a whole host of wonderful craters that look amazing when the lighting is oblique. During the summer and into the early autumn, it’s the later phases of the Moon are best positioned in the sky - the phases following full Moon. Unfortunately, this means viewing in the early hours but don’t worry as we’ve kept things simple. We just want to give you a taste of what a shadowed crater looks like for this marathon, so the going here is really pretty easy! First, locate the two craters Kepler and Copernicus which were marathon targets pointed out in Section 2. -

The Satrap of Western Anatolia and the Greeks

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2017 The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks Eyal Meyer University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons Recommended Citation Meyer, Eyal, "The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks" (2017). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2473. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2473 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2473 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks Abstract This dissertation explores the extent to which Persian policies in the western satrapies originated from the provincial capitals in the Anatolian periphery rather than from the royal centers in the Persian heartland in the fifth ec ntury BC. I begin by establishing that the Persian administrative apparatus was a product of a grand reform initiated by Darius I, which was aimed at producing a more uniform and centralized administrative infrastructure. In the following chapter I show that the provincial administration was embedded with chancellors, scribes, secretaries and military personnel of royal status and that the satrapies were periodically inspected by the Persian King or his loyal agents, which allowed to central authorities to monitory the provinces. In chapter three I delineate the extent of satrapal authority, responsibility and resources, and conclude that the satraps were supplied with considerable resources which enabled to fulfill the duties of their office. After the power dynamic between the Great Persian King and his provincial governors and the nature of the office of satrap has been analyzed, I begin a diachronic scrutiny of Greco-Persian interactions in the fifth century BC. -

9/15 JEFFREY JAMES HENDERSON William Goodwin Aurelio Professor

9/15 JEFFREY JAMES HENDERSON William Goodwin Aurelio Professor of Greek Language and Literature General Editor, Loeb Classical Library Fellow, American Academy of Arts and Sciences Department of Classical Studies 460 Park Drive Boston University Boston, MA 02215 745 Commonwealth Avenue, Rm. 435 (857) 250-4216 Boston, MA 02215 (617) 358-5072 or 2427 email: [email protected] EDUCATION PhD 1972 Harvard University MA 1970 Harvard University BA 1968 Kenyon College (summa cum laude) POSITIONS HELD Visiting Professor Spring 2010 Brown University Aurelio Professor of Greek 2002-- Boston University Dean of Arts and Sciences 2002-07 Boston University Professor and Chair 1991-2002 Boston University Visiting Professor 1986 Univ. California at Los Angeles Professor 1986-91 Univ. Southern California Associate Professor 1983-86 Univ. Southern California Visiting Professor 1982-83 Univ. Southern California Associate Professor 1978-82 Univ. of Michigan (Ann Arbor) Assistant Professor 1972-78 Yale University ACADEMIC HONORS Kenyon College Highest Honors in Classics Brain Prize in Classics Essay Prize in English Phi Beta Kappa Harvard Univ. Bowdoin Prize in Latin Prose Composition PRIZES AND HONORS Raubenheimer Distinguished Faculty Award (1991) University of Southern California Doctor of Humane Letters (1994) Kenyon College Charles J. Goodwin Award of Merit (2002) American Philological Association Fellow, American Academy of Arts and Sciences elected 2011 eProduct/Best in Humanities (2015) for digital LCL American Publishers Awards for Professional and Scholarly -

THE MYTH of ORPHEUS and EURYDICE in WESTERN LITERATURE by MARK OWEN LEE, C.S.B. B.A., University of Toronto, 1953 M.A., Universi

THE MYTH OF ORPHEUS AND EURYDICE IN WESTERN LITERATURE by MARK OWEN LEE, C.S.B. B.A., University of Toronto, 1953 M.A., University of Toronto, 1957 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OP PHILOSOPHY in the Department of- Classics We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA September, i960 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of The University of British Columbia Vancouver 8, Canada. ©he Pttttrerstt^ of ^riitsl} (Eolimtbta FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES PROGRAMME OF THE FINAL ORAL EXAMINATION FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY of MARK OWEN LEE, C.S.B. B.A. University of Toronto, 1953 M.A. University of Toronto, 1957 S.T.B. University of Toronto, 1957 WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 21, 1960 AT 3:00 P.M. IN ROOM 256, BUCHANAN BUILDING COMMITTEE IN CHARGE DEAN G. M. SHRUM, Chairman M. F. MCGREGOR G. B. RIDDEHOUGH W. L. GRANT P. C. F. GUTHRIE C. W. J. ELIOT B. SAVERY G. W. MARQUIS A. E. BIRNEY External Examiner: T. G. ROSENMEYER University of Washington THE MYTH OF ORPHEUS AND EURYDICE IN WESTERN Myth sometimes evolves art-forms in which to express itself: LITERATURE Politian's Orfeo, a secular subject, which used music to tell its story, is seen to be the forerunner of the opera (Chapter IV); later, the ABSTRACT myth of Orpheus and Eurydice evolved the opera, in the works of the Florentine Camerata and Monteverdi, and served as the pattern This dissertion traces the course of the myth of Orpheus and for its reform, in Gluck (Chapter V). -

10Great Features for Moon Watchers

Sinus Aestuum is a lava pond hemming the Imbrium debris. Mare Orientale is another of the Moon’s large impact basins, Beginning observing On its eastern edge, dark volcanic material erupted explosively and possibly the youngest. Lunar scientists think it formed 170 along a rille. Although this region at first appears featureless, million years after Mare Imbrium. And although “Mare Orien- observe it at several different lunar phases and you’ll see the tale” translates to “Eastern Sea,” in 1961, the International dark area grow more apparent as the Sun climbs higher. Astronomical Union changed the way astronomers denote great features for Occupying a region below and a bit left of the Moon’s dead lunar directions. The result is that Mare Orientale now sits on center, Mare Nubium lies far from many lunar showpiece sites. the Moon’s western limb. From Earth we never see most of it. Look for it as the dark region above magnificent Tycho Crater. When you observe the Cauchy Domes, you’ll be looking at Yet this small region, where lava plains meet highlands, con- shield volcanoes that erupted from lunar vents. The lava cooled Moon watchers tains a variety of interesting geologic features — impact craters, slowly, so it had a chance to spread and form gentle slopes. 10Our natural satellite offers plenty of targets you can spot through any size telescope. lava-flooded plains, tectonic faulting, and debris from distant In a geologic sense, our Moon is now quiet. The only events by Michael E. Bakich impacts — that are great for telescopic exploring. -

Relative Ages

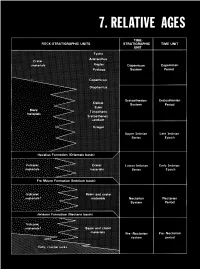

CONTENTS Page Introduction ...................................................... 123 Stratigraphic nomenclature ........................................ 123 Superpositions ................................................... 125 Mare-crater relations .......................................... 125 Crater-crater relations .......................................... 127 Basin-crater relations .......................................... 127 Mapping conventions .......................................... 127 Crater dating .................................................... 129 General principles ............................................. 129 Size-frequency relations ........................................ 129 Morphology of large craters .................................... 129 Morphology of small craters, by Newell J. Fask .................. 131 D, method .................................................... 133 Summary ........................................................ 133 table 7.1). The first three of these sequences, which are older than INTRODUCTION the visible mare materials, are also dominated internally by the The goals of both terrestrial and lunar stratigraphy are to inte- deposits of basins. The fourth (youngest) sequence consists of mare grate geologic units into a stratigraphic column applicable over the and crater materials. This chapter explains the general methods of whole planet and to calibrate this column with absolute ages. The stratigraphic analysis that are employed in the next six chapters first step in reconstructing -

Rethinking Athenian Democracy.Pdf

Rethinking Athenian Democracy A dissertation presented by Daniela Louise Cammack to The Department of Government in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of Political Science Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts January 2013 © 2013 Daniela Cammack All rights reserved. Professor Richard Tuck Daniela Cammack Abstract Conventional accounts of classical Athenian democracy represent the assembly as the primary democratic institution in the Athenian political system. This looks reasonable in the light of modern democracy, which has typically developed through the democratization of legislative assemblies. Yet it conflicts with the evidence at our disposal. Our ancient sources suggest that the most significant and distinctively democratic institution in Athens was the courts, where decisions were made by large panels of randomly selected ordinary citizens with no possibility of appeal. This dissertation reinterprets Athenian democracy as “dikastic democracy” (from the Greek dikastēs, “judge”), defined as a mode of government in which ordinary citizens rule principally through their control of the administration of justice. It begins by casting doubt on two major planks in the modern interpretation of Athenian democracy: first, that it rested on a conception of the “wisdom of the multitude” akin to that advanced by epistemic democrats today, and second that it was “deliberative,” meaning that mass discussion of political matters played a defining role. The first plank rests largely on an argument made by Aristotle in support of mass political participation, which I show has been comprehensively misunderstood. The second rests on the interpretation of the verb “bouleuomai” as indicating speech, but I suggest that it meant internal reflection in both the courts and the assembly. -

Arkeolojik Verilere Göre Doğu Trakya Kuzey Yolu*

Arkeolojik Verilere Göre Doğu Trakya Kuzey Yolu* Ergün Karaca** Öz Küçük Asya ile Avrupa arasında geçiş noktası konumundaki Doğu Trakya, her iki kıtadan gelen yolların geçiş ve birleşme yeri olmuştur. Kuzey Yolu, bölgeden geçen Via Egnatia ve Via Militaris ile birlikte üç ana yoldan biridir. Pontos Euksenos (Kara- deniz)’in batısı veya kuzeyine ya da tam tersi buradan Küçük Asya’ya doğru yapılan seferlerde MÖ 6. yüzyıldan MS 19. yüzyıla kadar tüm kara orduların kullandığı gü- zergâh olmuştur. Buna karşın Kuzey Yolu’nun güzergâhı üzerindeki arkeolojik veriler diğer yollar kadar değerlendirilmemiştir. Bu makalede arazi çalışması sırasında tespit edilen ve incelenen başta Kurtdere Köprüsü olmak üzere köprü, yol kalıntısı ve mil taşı kullanılarak Kuzey Yolu’nun Doğu Trakya Bölgesi içindeki güzergâhı tespit edilmeye çalışılmıştır. Ayrıca Kuzey Yolu’nun güneyindeki Via Militaris ile kuzeyindeki Salmy- dessos kenti ile bağlantı sağlayan yollar arkeolojik verilere göre değerlendirilmiştir. Anahtar Kelimeler: Antik Çağ’da Ulaşım, Mil taşı, Tabula Peutingeriana, Köprü. * Bu çalışma Trakya Üniversitesi, Bilimsel Araştırma Projeleri Birimi (TÜBAP) tarafından TÜBAP -2018/119 numaralı proje kapsamında desteklenmiştir. Makalede kullanılan harita ve fotoğraflar aksi belirtilmediği sürece tarafıma aittir. Ayrıca metinde kullanılan bilgiler, tarafımca 2014 yılında Kültür ve Turizm Bakanlığı’nın izni ve Kırklareli Müzesi’nin denetiminde gerçekleştirilen yüzey araştırmasının verileridir. ** Dr., Trakya Üniversitesi, Edebiyat Fakültesi, Arkeoloji Bölümü, Edirne/TÜRKİYE, [email protected] ORCID: 0000-0002-0270-3258 Makale Gönderim Tarihi: 02.05.2018 - Makale Kabul Tarihi: 09.01.2020 30 Ergün Karaca The North Road of Eastern Thrace according to Archeological Data Abstract East Thrace, which is the transition point between Asia Minor and Europe, has become the transit and the junction point of roads from both continents. -

THE SANCTUARY at EPIDAUROS and CULT-BASED NETWORKING in the GREEK WORLD of the FOURTH CENTURY B.C. a Thesis Presented in Partial

THE SANCTUARY AT EPIDAUROS AND CULT-BASED NETWORKING IN THE GREEK WORLD OF THE FOURTH CENTURY B.C. A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University by Pamela Makara, B.A. The Ohio State University 1992 Master's Examination Committee: Approved by Dr. Timothy Gregory Dr. Jack Ba I cer Dr. Sa u I Corne I I VITA March 13, 1931 Born - Lansing, Michigan 1952 ..... B.A. in Education, Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan 1952-1956, 1966-Present Teacher, Detroit, Michigan; Rochester, New York; Bowling Green, Ohio 1966-Present ............. University work in Education, Art History, and Ancient Greek and Roman History FIELDS OF STUDY Major Field: History Studies in Ancient Civi I izations: Dr. Timothy Gregory and Dr. Jack Balcer i i TABLE OF CONTENTS VITA i i LIST OF TABLES iv CHAPTER PAGE I. INTRODUCTION 1 I I. ANCIENT EPIDAUROS AND THE CULT OF ASKLEPIOS 3 I II. EPIDAURIAN THEARODOKOI DECREES 9 IV. EPIDAURIAN THEOROI 21 v. EPIDAURIAN THEARODOKOI INSCRIPTIONS 23 VI. AN ARGIVE THEARODOKOI INSCRIPTION 37 VII. A DELPHIC THEARODOKOI INSCRIPTION 42 VIII. SUMMARY 47 END NOTES 49 BIBLIOGRAPHY 55 APPENDICES A. EPIDAURIAN THEARODOKOI INSCRIPTIONS AND TRANSLATIONS 58 B. ARGIVE THEARODOKO I I NSCR I PT I ON 68 C. DELPHIC THEARODOKOI INSCRIPTION 69 D. THEARODOKO I I NSCR I PT IONS PARALLELS 86 iii LIST OF TABLES TABLE PAGE 1. Thearodoko i I nscr i pt ions Para I I e Is •••••••••••• 86 iv CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION Any evidence of I inkage in the ancient world is valuable because it clarifies the relationships between the various peoples of antiquity and the dealings they had with one another. -

Slaves, Sex, and Transgression in Greek Old Comedy

Slaves, Sex, and Transgression in Greek Old Comedy By Daniel Christopher Walin A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Classics in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Mark Griffith, Chair Professor Donald J. Mastronarde Professor Kathleen McCarthy Professor Emily Mackil Spring 2012 1 Abstract Slaves, Sex, and Transgression in Greek Old Comedy by Daniel Christopher Walin Doctor of Philosophy in Classics University of California, Berkeley Professor Mark Griffith, Chair This dissertation examines the often surprising role of the slave characters of Greek Old Comedy in sexual humor, building on work I began in my 2009 Classical Quarterly article ("An Aristophanic Slave: Peace 819–1126"). The slave characters of New and Roman comedy have long been the subject of productive scholarly interest; slave characters in Old Comedy, by contrast, have received relatively little attention (the sole extensive study being Stefanis 1980). Yet a closer look at the ancestors of the later, more familiar comic slaves offers new perspectives on Greek attitudes toward sex and social status, as well as what an Athenian audience expected from and enjoyed in Old Comedy. Moreover, my arguments about how to read several passages involving slave characters, if accepted, will have larger implications for our interpretation of individual plays. The first chapter sets the stage for the discussion of "sexually presumptive" slave characters by treating the idea of sexual relations between slaves and free women in Greek literature generally and Old Comedy in particular. I first examine the various (non-comic) treatments of this theme in Greek historiography, then its exploitation for comic effect in the fifth mimiamb of Herodas and in Machon's Chreiai. -

Fish Lists in the Wilderness

FISH LISTS IN THE WILDERNESS: The Social and Economic History of a Boiotian Price Decree Author(s): Ephraim Lytle Source: Hesperia: The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Vol. 79, No. 2 (April-June 2010), pp. 253-303 Published by: The American School of Classical Studies at Athens Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40835487 . Accessed: 18/03/2014 10:14 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The American School of Classical Studies at Athens is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Hesperia: The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 71.168.218.10 on Tue, 18 Mar 2014 10:14:19 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions HESPERIA 79 (2OIO) FISH LISTS IN THE Pages 253~3°3 WILDERNESS The Social and Economic History of a Boiotian Price Decree ABSTRACT This articlepresents a newtext and detailedexamination of an inscribedHel- lenisticdecree from the Boiotian town of Akraiphia (SEG XXXII 450) that consistschiefly of lists of fresh- and saltwaterfish accompanied by prices. The textincorporates improved readings and restoresthe final eight lines of the document,omitted in previouseditions. -

Argos in Greek Inter-Poleis Relations in the 4Th Century BC

Journal of Sustainable Development; Vol. 8, No. 7; 2015 ISSN 1913-9063 E-ISSN 1913-9071 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Argos in Greek Inter-Poleis Relations in the 4th Century BC Elena A. Venidiktova1 1 Kazan (Volga Region) Federal University, Kazan, Russia Correspondence: Elena A. Venidiktova, Kazan (Volga Region) Federal University, 420008, Kazan, Kremlyovskaya Street, 18, Russia. E-mail: [email protected] Received: June 15, 2015 Accepted: June 24, 2015 Online Published: June 30, 2015 doi:10.5539/jsd.v8n7p222 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/jsd.v8n7p222 Abstract The relevance of the research topic is determined by the fact that the 4th century BC for the Greek poleis was the time of regular inter-poleis conflicts in which a special role was played by Argos. Argos is poorly studied in modern historiography; its place in the historically developed system of Greek poleis has not been properly investigated and evaluated. The paper is aimed at examining the course of foreign policy of the polis of Argos in the 4th century BC and indicating its role in the inter-poleis conflicts. The key methodology of the research is made up by a set of methods based on the study of various data on the topic. The paper indicates the position of Argos in inter-poleis conflicts, reveals the facts of its aggressive foreign policy that was oriented to rival Sparta, presents the stages of activity of the Argives in establishing the state. The paper findings may be useful in academic studies while compiling general works on the military history of ancient Greece, or while running special courses devoted to the history of the political development of ancient Greece.