Full Draft 0708

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Killing of William Browder

THE KILLING OF WILLIAM BROWDER THE KILLING OF WILLIAM BROWDER Bill Browder, the fa lse crusader for justice and human rights and the self - styled No. 1 enemy of Vladimir Putin has perpetrated a brazen and dangerous deception upon the Weste rn world. This book traces the anatomy of this deception, unmasking the powerful forces that are pushing the West ern world toward yet another great war with Russia. ALEX KRAINER EQUILIBRIUM MONACO First published in Monaco in 20 17 Copyright © 201 7 by Alex Krainer ISBN 978 - 2 - 9556923 - 2 - 5 Material contained in this book may be reproduced with permission from its author and/or publisher, except for attributed brief quotations Cover page design, content editing a nd copy editing by Alex Krainer. Set in Times New Roman, book title in Imprint MT shadow To the people of Russia and the United States wh o together, hold the keys to the future of humanity. Enlighten the people generally, and tyranny and oppressions of body and mind will vanish like the evil spirits at the dawn of day. Thomas Jefferson Table of Contents 1. Bill Browder and I ................................ ................................ ............... 1 Browder’s 2005 presentation in Monaco ................................ .............. 2 Harvard club presentation in 2010 ................................ ........................ 3 Ru ssophobia and Putin - bashing in the West ................................ ......... 4 Red notice ................................ ................................ ............................ 6 Reading -

Which Developmentalism

1 Which developmentalism? A Keynesian-Institutionalist proposal Fernando Ferrari Filho Professor of Economics at Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul and Researcher at National Council for Scientific and Technological Development, Brazil. [email protected] Pedro Cezar Dutra Fonseca Professor of Economics at Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul and Researcher at National Council for Scientific and Technological Development, Brazil. [email protected] Abstract: Academic discussion of Brazil’s economic growth is currently framed in terms of export-led growth and wage-led growth, identified, respectively, with the new- developmentalism and the social-developmentalism approaches. This article presents a Keynesian-Institutionalist proposal to the Brazilian economy based on a wage-led regime without neglecting the long run balance of payment on current account requirement to ensure macroeconomic stability in the Brazilian economy. Keywords: New-developmentalism, social-developmentalism, Keynesian- Institutionalist, wage-led, profit-led and export-led growths. JEL Codes: B, B5. 1 Introduction While priority was given to monetary stability during the 1980s and 1990s, economic growth has gradually been finding its way back to both theoretical economic debate and economic policy discussions in Brazil since the 2000s. This has been due partly, on the one hand, to the election of various governments critical of neoliberalism in Latin America and, on the other hand, to the 2007-2008 financial crisis, which restored interventionism to the agenda, -

Specialised Asset Management

specialised research and investment group Russian Power: The Greatest Sector Reform on Earth www.sprin-g.com November 2010 specialised research and investment group Specialised Research and Investment Group (SPRING) Manage Investments in Russian Utilities: - HH Generation - #1 among EM funds (12 Months Return)* #2 among EM funds (Monthly return)** David Herne - Portfolio Manager Previous positions: Member, Board of Directors - Unified Energy Systems, Federal Grid Company, RusHydro, TGK-1, TGK-2, TGK-4, OGK-3, OGK-5, System Operator, Aeroflot, etc. (2000-2008) Chairman, Committee for Strategy and Reform - Unified Energy Systems (2001-2008) Boston Consulting Group, Credit Suisse First Boston, Brunswick. * Top 10 (by 12 Months Return) Emerging Markets (E. Europe/CIS) funds in the world by BarclayHedge as of 30 September 2010 ** Top 10 (by Monthly Return) Emerging Markets (E. Europe/CIS) funds in the world by BarclayHedge as of 31 August 2010 2 specialised research and investment group Russian power sector reform: Privatization Pre-Reform Post-Reform Government Government 52% 1 RusHydro 1 FSK RAO ES RAO UES 58% 79% hydro generation HV distribution 53% Far East Holding control control Independent energos 53% 1 MRSK Holding 14 TGKs 0% (Bashkir, Novosibirsk, ~72 energos 0% generation (CHP) generation Irkutsk, Tat) 35 federal plants transmission thermal 11 MRSK distribution 51% hydro LV distribution 0% ~72 SupplyCos supply 6 OGKs other 0% generation 45% InterRAO 0% ~100 RepairCos Source: UES, Companies Data, SPRING research 3 specialised research -

The Russia You Never Met

The Russia You Never Met MATT BIVENS AND JONAS BERNSTEIN fter staggering to reelection in summer 1996, President Boris Yeltsin A announced what had long been obvious: that he had a bad heart and needed surgery. Then he disappeared from view, leaving his prime minister, Viktor Cher- nomyrdin, and his chief of staff, Anatoly Chubais, to mind the Kremlin. For the next few months, Russians would tune in the morning news to learn if the presi- dent was still alive. Evenings they would tune in Chubais and Chernomyrdin to hear about a national emergency—no one was paying their taxes. Summer turned to autumn, but as Yeltsin’s by-pass operation approached, strange things began to happen. Chubais and Chernomyrdin suddenly announced the creation of a new body, the Cheka, to help the government collect taxes. In Lenin’s day, the Cheka was the secret police force—the forerunner of the KGB— that, among other things, forcibly wrested food and money from the peasantry and drove some of them into collective farms or concentration camps. Chubais made no apologies, saying that he had chosen such a historically weighted name to communicate the seriousness of the tax emergency.1 Western governments nod- ded their collective heads in solemn agreement. The International Monetary Fund and the World Bank both confirmed that Russia was experiencing a tax collec- tion emergency and insisted that serious steps be taken.2 Never mind that the Russian government had been granting enormous tax breaks to the politically connected, including billions to Chernomyrdin’s favorite, Gazprom, the natural gas monopoly,3 and around $1 billion to Chubais’s favorite, Uneximbank,4 never mind the horrendous corruption that had been bleeding the treasury dry for years, or the nihilistic and pointless (and expensive) destruction of Chechnya. -

Developmentalism, Modernity, and Dependency Theory in Latin America

Developmentalism, Modernity, and Dependency Theory in Latin America Ramón Grosfoguel The Latin American dependentistas produced a knowledge that criticized the Eurocentric assumptions of the cepalistas,includingtheorthodoxMarxistandtheNorthAmericanmodern- ization theories. The dependentista school critique of stagism and develop- mentalism was an important intervention that transformed the imaginary of intellectual debates in many parts of the world. However, I will argue that many dependentistas were still caught in the developmentalism, and in some cases even the stagism, that they were trying to overcome. Moreover, although the dependentistas’ critique of stagism was important in denying the “denial of coevalness” that Johannes Fabian (1983) describes as central to Eurocentric constructions of “otherness,” some dependentistas replaced it with new forms of denial of coevalness. The first part of this article dis- cusses developmentalist ideology and what I call “feudalmania” as part of the longue durée of modernity in Latin America. The second part discusses the dependentistas’ developmentalism. The third part is a critical discussion of Fernando Henrique Cardoso’s version of dependency theory. Finally, the fourth part discusses the dependentistas’ concept of culture. Developmentalist Ideology and Feudalmania as Part of the Ideology of Modernity in Latin America There is a tendency to present the post-1945 development debates in Latin America as unprecedented. In order to distinguish continuity from dis- continuity, we must place the 1945–90 development debates in the context of the longue durée of Latin American history. The 1945–90 development Nepantla: Views from South 1:2 Copyright 2000 by Duke University Press 347 348 Nepantla debates in Latin America, although seemingly radical, in fact form part of the longue durée of the geoculture of modernity that has dominated the modern world-system since the French Revolution in the late eighteenth century. -

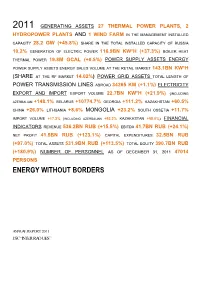

Energy Without Borders

2011 GENERATING ASSETS 27 THERMAL POWER PLANTS, 2 HYDROPOWER PLANTS AND 1 WIND FARM IN THE MANAGEMENT INSTALLED CAPACITY 28.2 GW (+45.8%) SHARE IN THE TOTAL INSTALLED CAPACITY OF RUSSIA 10.2% GENERATION OF ELECTRIC POWER 116.9BN KW*H (+37.3%) BOILER HEAT THERMAL POWER 19.8M GCAL (+0.5%) POWER SUPPLY ASSETS ENERGY POWER SUPPLY ASSETS ENERGY SALES VOLUME AT THE RETAIL MARKET 143.1BN KW*H (SHARE AT THE RF MARKET 14.02%) POWER GRID ASSETS TOTAL LENGTH OF POWER TRANSMISSION LINES ABROAD 34265 KM (+1.1%) ELECTRICITY EXPORT AND IMPORT EXPORT VOLUME 22.7BN KW*H (+21.9%) (INCLUDING AZERBAIJAN +148.1% BELARUS +10774.7% GEORGIA +111.2% KAZAKHSTAN +60.5% CHINA +26.0% LITHUANIA +8.6% MONGOLIA +23.2% SOUTH OSSETIA +11.7% IMPORT VOLUME +17.2% (INCLUDING AZERBAIJAN +93.2% KAZAKHSTAN +58.0%) FINANCIAL INDICATORS REVENUE 536.2BN RUB (+15.5%) EBITDA 41.7BN RUB (+24.1%) NET PROFIT 41.5BN RUB (+123.1%) CAPITAL EXPENDITURES 32.5BN RUB (+97.0%) TOTAL ASSETS 531.9BN RUB (+113.5%) TOTAL EQUITY 390.7BN RUB (+180.9%) NUMBER OF PERSONNEL AS OF DECEMBER 31, 2011 47014 PERSONS ENERGY WITHOUT BORDERS ANNUAL REPORT 2011 JSC “INTER RAO UES” Contents ENERGY WITHOUT BORDERS.........................................................................................................................................................1 ADDRESS BY THE CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS AND THE CHAIRMAN OF THE MANAGEMENT BOARD OF JSC “INTER RAO UES”..............................................................................................................8 1. General Information about the Company and its Place in the Industry...........................................................10 1.1. Brief History of the Company......................................................................................................................... 10 1.2. Business Model of the Group..........................................................................................................................12 1.4. -

a Leading Energy Company in the Nordic Area

- a leading energy company in the Nordic area Presentation for investors September 2007 Disclaimer This presentation does not constitute an invitation to underwrite, subscribe for, or otherwise acquire or dispose of any Fortum shares. Past performance is no guide to future performance, and persons needing advice should consult an independent financial adviser. 2 • Fortum today • European power markets • Russia • Financials / outlook • Supplementary material 3 Fortum's strategy Fortum focuses on the Nordic and Baltic Rim markets as a platform for profitable growth Become the leading Become the power and heat energy supplier company of choice Benchmark business performance 4 Presence in focus market areas Nordic Generation 53.2 TWh Electricity sales 60.2 TWh Distribution cust. 1.6 mill. Electricity cust. 1.3 mill. NW Russia Heat sales 20.1 TWh (in associated companies) Power generation ~6 TWh Heat production ~7 TWh Baltic countries Heat sales 1.0 TWh Poland Distribution cust. 23,000 Heat sales 3.6 TWh Electricity sales 8 GWh 2006 numbers 5 Fortum Business structure Fortum Markets Fortum's comparable Large operating profit in 2006 NordicNordic customers EUR 1,437 million Fortum wholesalewholesale Small Power marketmarket customers Generation Nord Pool and Markets 0% bilateral Other retail companies Deregulated Distribution 17% Regulated Transmission Power and system Fortum Heat 17% Generation services Distribution 66% 6 Strong financial position ROE (%) EPS, cont. (EUR) Total assets (EUR billion) 20 1.50 1.42 20.0 16.8 17.5 17.3 1.22 18 15.1 -

Russiske Mynter Russian Coins 1021-1024 Russiske MYNTER / Russian COINS

RUSSISKE MYNTER / ruSSIAN COINS Russiske mynter Russian coins 1021-1024 RUSSISKE MYNTER / ruSSIAN COINS RUSSISKE myntER/RUSSIAn coINS PETER I 1689-1725 1021 Rubel 1704. Red Mint Bitkin 797 1+ 30 000 Peter the Great (ruled 1682–1725) and the first decimal coinage The reign of Peter I (the Great) is generally regarded as a watershed in Russian history, noted for a programme of extensive military, civil and social reforms that transformed Russia from an isolated agricultural society into a major European power. Early in his career, Peter toured Europe (sometimes in disguise) and educated himself in Western culture and science, as well as naval and military techniques. On his return to Russia he set about ‘modernizing’ or ‘westernizing’ the country, as well as extending its boundaries through a number of military campaigns. In 1703, during the Great Northern War with Sweden, Peter captured land on the Baltic Sea, where he founded his new capital, St Petersburg. This modern city, built in Western style, was intended to become the centre of new Russia just as Moscow had been the centre of old. The monetary system of Russia also changed dramatically as part of Peter the Great’s extensive reforms. In 1700 the czar decreed a decimal coinage system for Russia – the first in history – with 100 kopeks equal to one rouble. The first (copper) kopek and (silver) rouble coins under the new system appeared in 1704. As well as introducing a decimal coinage, Peter I also banned the use of foreign coins in Russia. Moreover, in order to ensure a standard size and weight for the new Russian coins, the czar ordered that coins should no longer be minted by hand, but should be machine-struck. -

Reform and Human Rights the Gorbachev Record

100TH-CONGRESS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES [ 1023 REFORM AND HUMAN RIGHTS THE GORBACHEV RECORD REPORT SUBMITTED TO THE CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATES BY THE COMMISSION ON SECURITY AND COOPERATION IN EUROPE MAY 1988 Printed for the use of the Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON: 1988 84-979 = For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, Congressional Sales Office U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402 COMMISSION ON SECURITY AND COOPERATION IN EUROPE STENY H. HOYER, Maryland, Chairman DENNIS DeCONCINI, Arizona, Cochairman DANTE B. FASCELL, Florida FRANK LAUTENBERG, New Jersey EDWARD J. MARKEY, Massachusetts TIMOTHY WIRTH, Colorado BILL RICHARDSON, New Mexico WYCHE FOWLER, Georgia EDWARD FEIGHAN, Ohio HARRY REED, Nevada DON RITTER, Pennslyvania ALFONSE M. D'AMATO, New York CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey JOHN HEINZ, Pennsylvania JACK F. KEMP, New York JAMES McCLURE, Idaho JOHN EDWARD PORTER, Illinois MALCOLM WALLOP, Wyoming EXECUTIvR BRANCH HON. RICHARD SCHIFIER, Department of State Vacancy, Department of Defense Vacancy, Department of Commerce Samuel G. Wise, Staff Director Mary Sue Hafner, Deputy Staff Director and General Counsel Jane S. Fisher, Senior Staff Consultant Michael Amitay, Staff Assistant Catherine Cosman, Staff Assistant Orest Deychakiwsky, Staff Assistant Josh Dorosin, Staff Assistant John Finerty, Staff Assistant Robert Hand, Staff Assistant Gina M. Harner, Administrative Assistant Judy Ingram, Staff Assistant Jesse L. Jacobs, Staff Assistant Judi Kerns, Ofrice Manager Ronald McNamara, Staff Assistant Michael Ochs, Staff Assistant Spencer Oliver, Consultant Erika B. Schlager, Staff Assistant Thomas Warner, Pinting Clerk (11) CONTENTS Page Summary Letter of Transmittal .................... V........................................V Reform and Human Rights: The Gorbachev Record ................................................ -

RUSSIA WATCH No.2, August 2000 Graham T

RUSSIA WATCH No.2, August 2000 Graham T. Allison, Director Editor: Ben Dunlap Strengthening Democratic Institutions Project Production Director: Melissa C..Carr John F. Kennedy School of Government Researcher: Emily Van Buskirk Harvard University Production Assistant: Emily Goodhue SPOTLIGHT ON RUSSIA’S OLIGARCHS On July 28 Russian President Vladimir Putin met with 21 of Russia’s most influ- ential businessmen to “redefine the relationship between the state and big busi- ness.” At that meeting, Putin assured the tycoons that privatization results would remained unchallenged, but stopped far short of offering a general amnesty for crimes committed in that process. He opened the meeting by saying: “I only want to draw your attention straightaway to the fact that you have yourselves formed this very state, to a large extent through political and quasi-political structures under your control.” Putin assured the oligarchs that recent investi- The Kremlin roundtable comes at a crucial time for the oligarchs. In the last gations were not part of a policy of attacking big business, but said he would not try to restrict two months, many of them have found themselves subjects of investigations prosecutors who launch such cases. by the General Prosecutor’s Office, Tax Police, and Federal Security Serv- ice. After years of cozying up to the government, buying up the state’s most valuable resources in noncompetitive bidding, receiving state-guaranteed loans with little accountability, and flouting the country’s tax laws with imp u- nity, the heads of some of Russia’s leading financial-industrial groups have been thrust under the spotlight. -

Social Transition in the North, Vol. 1, No. 4, May 1993

\ / ' . I, , Social Transition.in thb North ' \ / 1 \i 1 I '\ \ I /? ,- - \ I 1 . Volume 1, Number 4 \ I 1 1 I Ethnographic l$ummary: The Chuko tka Region J I / 1 , , ~lexdderI. Pika, Lydia P. Terentyeva and Dmitry D. ~dgo~avlensly Ethnographic Summary: The Chukotka Region Alexander I. Pika, Lydia P. Terentyeva and Dmitry D. Bogoyavlensky May, 1993 National Economic Forecasting Institute Russian Academy of Sciences Demography & Human Ecology Center Ethnic Demography Laboratory This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. DPP-9213l37. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recammendations expressed in this material are those of the author@) and do not ncccssarily reflect the vim of the National Science Foundation. THE CHUKOTKA REGION Table of Contents Page: I . Geography. History and Ethnography of Southeastern Chukotka ............... 1 I.A. Natural and Geographic Conditions ............................. 1 I.A.1.Climate ............................................ 1 I.A.2. Vegetation .........................................3 I.A.3.Fauna ............................................. 3 I1. Ethnohistorical Overview of the Region ................................ 4 IIA Chukchi-Russian Relations in the 17th Century .................... 9 1I.B. The Whaling Period and Increased American Influence in Chukotka ... 13 II.C. Soviets and Socialism in Chukotka ............................ 21 I11 . Traditional Culture and Social Organization of the Chukchis and Eskimos ..... 29 1II.A. Dwelling .............................................. -

World Bank Group Assistance to Low-Income Fragile and Conflict-Affected States

World Bank Group Assistance to Low-Income Fragile and Conflict-Affected States An Independent Evaluation Appendixes Contents Abbreviations Appendixes APPENDIX A. EVALUATION METHODOLOGY .................................................................................... 1 APPENDIX B. CAMEROON ................................................................................................................... 5 APPENDIX C. DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO ....................................................................... 17 APPENDIX D. NEPAL ........................................................................................................................... 29 APPENDIX E. SIERRA LEONE ............................................................................................................ 41 APPENDIX F. SOLOMON ISLANDS .................................................................................................... 53 APPENDIX G. REPUBLIC OF YEMEN ................................................................................................. 65 APPENDIX H. PERCEPTION SURVEY OF WORLD BANK GROUP STAFF AND STAKEHOLDERS77 APPENDIX I. FRAGILE AND CONFLICT-AFFECTED STATES STATUS AND THE MILLENNIUM DEVELOPMENT GOALS ...................................................................................................................... 87 APPENDIX J. ASSESSING THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN DEVELOPMENT POLICY LOANS AND COUNTRY POLICY AND INSTITUTIONAL ASSESSMENT RATINGS ............................................... 97 APPENDIX K. WORLD BANK