CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION Background to the Study Ever Since

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

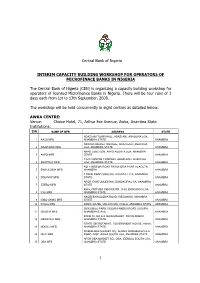

Interim Capacity Building for Operators of Microfinance Banks

Central Bank of Nigeria INTERIM CAPACITY BUILDING WORKSHOP FOR OPERATORS OF MICROFINACE BANKS IN NIGERIA The Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) is organizing a capacity building workshop for operators of licensed Microfinance Banks in Nigeria. There will be four runs of 3 days each from 1st to 13th September, 2008. The workshop will be held concurrently in eight centres as detailed below: AWKA CENTRE: Venue: Choice Hotel, 71, Arthur Eze Avenue, Awka, Anambra State. Institutions: S/N NAME OF MFB ADDRESS STATE ADAZI ANI TOWN HALL, ADAZI ANI, ANAOCHA LGA, 1 AACB MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA NKWOR MARKET SQUARE, ADAZI-ENU, ANAOCHA 2 ADAZI-ENU MFB LGA, ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA AKPO JUNCTION, AKPO AGUATA LGA, ANAMBRA 3 AKPO MFB STATE ANAMBRA CIVIC CENTRE COMPLEX, ADAZI-ENU, ANAOCHA 4 BESTWAY MFB LGA, ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA NO 1 MISSION ROAD EKWULOBIA P.M.B.24 AGUTA, 5 EKWULOBIA MFB ANAMBRA ANAMBRA 1 BANK ROAD UMUCHU, AGUATA L.G.A, ANAMBRA 6 EQUINOX MFB STATE ANAMBRA AFOR IGWE UMUDIOKA, DUNUKOFIA LGA, ANAMBRA 7 EZEBO MFB STATE ANAMBRA KM 6, ONITHSA OKIGWE RD., ICHI, EKWUSIGO LGA, 8 ICHI MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA NNOBI/EKWULOBIA ROAD, IGBOUKWU, ANAMBRA 9 IGBO-UKWU MFB STATE ANAMBRA 10 IHIALA MFB BANK HOUSE, ORLU ROAD, IHIALA, ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA EKWUSIGO PARK, ISUOFIA-NNEWI ROAD, ISUOFIA, 11 ISUOFIA MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA ZONE 16, NO.6-9, MAIN MARKET, NKWO-NNEWI, 12 MBAWULU MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA STATE SECRETARIAT, GOVERNMENT HOUSE, AWKA, 13 NDIOLU MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA NGENE-OKA MARKET SQ., ALONG AMAWBIA/AGULU 14 NICE MFB ROAD, NISE, AWKA SOUTH -

NIGERIA COUNTRY of ORIGIN INFORMATION (COI) REPORT COI Service

NIGERIA COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION (COI) REPORT COI Service 6 January 2012 NIGERIA 6 JANUARY 2012 Contents Preface Latest news EVENTS IN NIGERIA FROM 16 DECEMBER 2011 TO 3 JANUARY 2012 Useful news sources for further information REPORTS ON NIGERIA PUBLISHED OR ACCESSED AFTER 15 DECEMBER 2011 Paragraphs Background Information 1. GEOGRAPHY ............................................................................................................ 1.01 Map ........................................................................................................................ 1.07 2. ECONOMY ................................................................................................................ 2.01 3. HISTORY (1960 – 2011) ........................................................................................... 3.01 Independence (1960) – 2010 ................................................................................ 3.02 Late 2010 to February 2011 ................................................................................. 3.04 4. RECENT DEVELOPMENTS (MARCH 2011 TO NOVEMBER 2011) ...................................... 4.01 Elections: April, 2011 ....................................................................................... 4.01 Inter-communal violence in the middle belt of Nigeria ................................. 4.08 Boko Haram ...................................................................................................... 4.14 Human rights in the Niger Delta ......................................................................... -

Electoral Violence and the Survival of Democracy in Nigeria’Sfourth Republic: a Historical Perspective

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by CSCanada.net: E-Journals (Canadian Academy of Oriental and Occidental Culture,... ISSN 1712-8056[Print] Canadian Social Science ISSN 1923-6697[Online] Vol. 10, No. 3, 2014, pp. 140-148 www.cscanada.net DOI:10.3968/4593 www.cscanada.org Electoral Violence and the Survival of Democracy in Nigeria’sFourth Republic: A Historical Perspective Adesola Samson Adesote[a],*; John O. Abimbola[b] [a]Lecturer, Department of History & Diplomatic Studies, McPherson University, Seriki-Sotayo, Nigeria INTRODUCTION [b]Principal Lecturer, Department of History, Adeyemi College of In every stable democratic society, election remains Education, Ondo, Nigeria. * the essential ingredient of transitory process from Corresponding author. one civilian administration to another. Elections have Received 11 January 2014; accepted 9 April 2014 become an integral part of representative democracy Pulished online 18 April 2014 that by and large prevails across the world. According to Lindberg (2003), every modern vision of representative Abstract democracy entails the notion of elections as the primary The historical trajectory of electoral process in the means of selection of political decision makers. Thus, it post colonial Nigeria is characterised by violence. In is incomprehensible in contemporary times to think of fact, recent manifestations of electoral violence, most democracy without linking it to the idea and practice of importantly since the birth of the Fourth Republic in 1999 elections. Ojo (2007), described election as the ‘hallmark have assumed an unprecedented magnitude and changing of democracy’ while Chiroro (2005) sees it as the ‘heart form, resulting in instability in democratic consolidation of the democratic order’. -

Spatial Distributions of Aquifer Hydraulic Properties from Pumping Test Data in Anambra State, Southeastern Nigeria

American Journal of Geophysics, Geochemistry and Geosystems Vol. 5, No. 4, 2019, pp. 119-128 http://www.aiscience.org/journal/aj3g ISSN: 2381-7143 (Print); ISSN: 2381-7151 (Online) Spatial Distributions of Aquifer Hydraulic Properties from Pumping Test Data in Anambra State, Southeastern Nigeria Christopher Chukwudi Ezeh1, Austin Chukwuemeka Okonkwo1, *, Emeka Udeze2 1Department of Geology and Mining, Enugu State University of Science and Technology, Enugu, Nigeria 2Anambra State Rural Water and Sanitation Agency (ANARUWASA), Awka, Nigeria Abstract Spatial distributions of aquifer hydraulic properties were carried out from direct pumping test data in Anambra State, Southeastern Nigeria. The study area lies within longitudes 06° 38I and 007° 15IE and latitudes 05°42I and 006°45IN within an area extent of about 4844sqkm (1870sqmi), underlain by four main geological formations. Pump testing was carried out in over one hundred (100) locations in the study area. The single-well test approach was used, employing the constant discharge and recovery methods. The Cooper-Jacob’s straight-line method was used to analyze the pump test results. This enabled the computing of the aquifer hydraulic properties. Correlated borehole logs show total depth range of 80meters to 250meters, with lithologic sequence of top sandy clay – medium to coarse grained sand – clay/shale – sand/sandstone, with the medium to coarse grained sand thickly underlying the central part of the study area. Static water level ranges from 100meters to 260meters at the central part and 10meters to 90meters at the adjoining areas. Aquifer transmissivity values range from 5m2/day to 80m2/day, indicating variable transmissivity potentials, while hydraulic conductivity values range from 0.5m/day to 6.0m/day. -

Growth of the Catholic Church in the Onitsha Province Op Eastern Nigeria 1905-1983 V 14

THE CONTRIBUTION OP THE LAITY TO THE GROWTH OF THE CATHOLIC CHURCH IN THE ONITSHA PROVINCE OP EASTERN NIGERIA 1905-1983 V 14 - I BY REV. FATHER VINCENT NWOSU : ! I i A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DOCTOR OP PHILOSOPHY , DEGREE (EXTERNAL), UNIVERSITY OF LONDON 1988 ProQuest Number: 11015885 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11015885 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 s THE CONTRIBUTION OF THE LAITY TO THE GROWTH OF THE CATHOLIC CHURCH IN THE ONITSHA PROVINCE OF EASTERN NIGERIA 1905-1983 By Rev. Father Vincent NWOSU ABSTRACT Recent studies in African church historiography have increasingly shown that the generally acknowledged successful planting of Christian Churches in parts of Africa, especially the East and West, from the nineteenth century was not entirely the work of foreign missionaries alone. Africans themselves participated actively in p la n tin g , sustaining and propagating the faith. These Africans can clearly be grouped into two: first, those who were ordained ministers of the church, and secondly, the lay members. -

An Action Research Project in Nigeria

Building infrastructures for peace: an action research project in Nigeria Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree Doctor of Philosophy: Public Management (Peacebuilding) in the Faculty of Management Sciences at Durban University of Technology Oseremen Irene December 2014 Supervisor: Professor Geoff Harris Co-supervisor: Dr Sylvia Kaye Declaration I, Oseremen Felix IRENE, declare that I. The research reported in this dissertation/thesis, except where otherwise indicated, is my original research. II. This dissertation/thesis has not been submitted for any degree or examination at any other university. III. This thesis does not contain other persons’ data, pictures, graphs or other information, unless specifically acknowledged as being sourced from other persons. IV. This dissertation/thesis does not contain other persons’ writing, unless specifically acknowledged as being sourced from other researchers. Where other written sources have been quoted, then: a. their words have been re-written but the general information attributed to them has been referenced: b. where their exact words have been used, their writing has been placed inside quotation marks and referenced. V. This thesis does not contain text, graphics or tables copied and pasted from the Internet, unless specifically acknowledged, with the source being detailed in the dissertation/thesis and in the References sections. Signature: Abstract Nigeria has witnessed a plethora of conflicts and violence especially since her post independent era. Direct and structural violence as well as cultural violence have largely dotted her history. The various nature of violence that have over the years keeps the country teetering at the verge of precipice include, resource-based conflict in the Niger Delta, indigenes-settlers conflicts, gender-based conflicts, ethno- religious conflicts, electoral cum political conflicts and the recent Boko Haram violent menace that has claimed at least 13,000 lives in Nigeria. -

Research Report

1.1 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION Soil erosion is the systematic removal of soil, including plant nutrients, from the land surface by various agents of denudation (Ofomata, 1985). Water being the dominant agent of denudation initiates erosion by rain splash impact, drag and tractive force acting on individual particles of the surface soil. These are consequently transported seizing slope advantage for deposition elsewhere. Soil erosion is generally created by initial incision into the subsurface by concentrated runoff water along lines or zones of weakness such as tension and desiccation fractures. As these deepen, the sides give in or slide with the erosion of the side walls forming gullies. During the Stone Age, soil erosion was counted as a blessing because it unearths valuable treasures which lie hidden below the earth strata like gold, diamond and archaeological remains. Today, soil erosion has become an endemic global problem, In the South eastern Nigeria, mostly in Anambra State, it is an age long one that has attained a catastrophic dimension. This environmental hazard, because of the striking imprints on the landscape, has sparked off serious attention of researchers and government organisations for sometime now. Grove(1951); Carter(1958); Floyd(1965); Ofomata (1964,1965,1967,1973,and 1981); all made significant and refreshing contributions on the processes and measures to combat soil erosion. Gully Erosion is however the prominent feature in the landscape of Anambra State. The topography of the area as well as the nature of the soil contributes to speedy formation and spreading of gullies in the area (Ofomata, 2000);. 1.2 Erosion Types There are various types of erosion which occur these include Soil Erosion Rill Erosion Gully Erosion Sheet Erosion 1.2.1 Soil Erosion: This has been occurring for some 450 million years, since the first land plants formed the first soil. -

Harnischfeger Igbo Nationalism & Biafra Long Paper

Igbo Nationalism and Biafra Johannes Harnischfeger, Frankfurt Content 0. Foreword .................................................................... 3 1. Introduction 1.1 The War and its Legacy ....................................... 8 1.2 Trapped in Nigeria.............................................. 13 1.2 Nationalism, Religion, and Global Identities....... 17 2. Patterns of Ethnic and Regional Conflicts 2.1 Early Nationalism ............................................... 23 2.2 The Road to Secession ...................................... 31 3. The Defeat of Biafra 3.1 Left Alone ........................................................... 38 3.2 After the War ...................................................... 44 4. Global Identities and Religion 4.1 9/11 in Nigeria .................................................... 52 4.2 Christian Solidarity ............................................. 59 5. Nationalist Organisations 5.1 Igbo Presidency or Secession............................ 64 2 5.2 Internal Divisions ................................................ 70 6. Defining Igboness 6.1 Reaching for the Stars........................................ 74 6.2 Secular and Religious Nationalism..................... 81 7. A Secular, Afrocentric Vision 7.1 A Community of Suffering .................................. 86 7.2 Roots .................................................................. 91 7.3 Modernism.......................................................... 97 8. The Covenant with God 8.1 In Exile............................................................. -

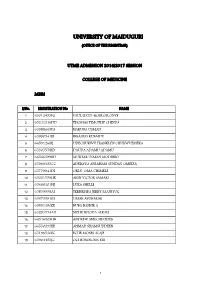

Unimaid Utme 2016 2017 First Batch

UNIVERSITY OF MAIDUGURI (OFFICE OF THE REGISTRAR) UTME ADMISSION 2016/2017 SESSION COLLEGE OF MEDICINE MBBS S/No. REGISTRATION No. NAME 1 65012453FG PAUL LIZZY-ROSE OILONYE 2 65241316DD THOMAS TIMOTHY CHINDA 3 65988663FA HARUNA USMAN 4 65880541EI IBRAHIM KUBAIDU 5 66531268IJ UDECHUKWU FRANKLYN CHUKWUEMEKA 6 65305578ID DAUDA ADAMU ADAMU 7 66546199BD MUKTAR USMAN MODIBBO 8 65989125CC ADEBAYO ABRAHAM SUNDAY OMEIZA 9 65759941DI ORLU-OMA CHIMELE 10 65021759HE AKIN VICTOR SAMARI 11 65488101HJ LUKA SHELLE 12 65859958AI TERHEMBA JERRY SAANIYOL 13 65875581IH UMAR ABUBAKAR 14 65891180EE BUBA BASHIR A 15 65295774AH NUHU RHODA ALKALI 16 66546503HB ANDREW MELCHIZEDEK 17 66550295EE AHMAD SHAMSUDDEEN 18 65198536EC ECHE MOSES ALAJE 19 65904453JC OCHE PRINCESS EHI 1 20 65299718AJ ABDULMUMIN ABUBAKAR 21 65459752FH OBI SOMTO 22 65780434FH JATTO ISA ENERO 23 66200732GG MICHAEL BLESSING 24 66299464BB MICHAEL KISLON SHITNAN 25 65903857DH USMAN ADAMA 26 66215998FC GWASKI ISAAC DIKA 27 66496897JB MOHAMMED ADAMU DUMBULWA 28 65243376GB TAHIR MUHAMMAD ARABO 29 66048182HA JERRY LEAH 30 65885079BE AHMED ABBA 31 65858960JC GAMBO LAWI 32 66246168ED SAMAILA BITRUS VISION 33 65919477CI OBI PETER CHIGOZIE 34 65548790IB GADZAMA JANADA YOHANNA 35 66193123AB MOSES MATTHEW TAIYE 36 65780170HD AERNAN SEDOO 37 65786350GA ZAKARIYYA ABDULMUMIN SANI 38 66324429JH OJIMADU CHIDINDU GODSWILL 39 65527190IF MBAYA ENOCH SAMUEL 40 65199053ED GAGA TERNGUNAN ERIC 41 65534793HB ROBERT RAKEAL 42 65305105EH YAK'OR TONGRIYANG DAWEET 43 65299765GC GONI AISHA UMAR 44 65136595BD AFOLABI ABDULWAHAB -

Governance and Human Security in Anambra State, 1999-2007

GOVERNANCE AND HUMAN SECURITY IN ANAMBRA STATE, 1999-2007 BY GINIKA UCHE-NWANKWO PG/MSC/08/48783 DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA NSUKKA FEBRUARY, 2010 i GOVERNANCE AND HUMAN SECURITY IN ANAMBRA STATE, 1999-2007 BY GINIKA UCHE-NWANKWO PG/MSC/08/48783 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF MASTER OF SCIENCE (MS.c) IN POLITICAL SCIENCE (GOVERNMENT) TO THE DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA, NSUKKA. SUPERVISOR: PROF. JONAH ONUOHA Ph.D. FEBRUARY, 2010 ii APPROVAL PAGE GINIKA UCHE-NWANKWO a postgraduate student in the Department of Political Science with Registration Number PG/MS.c/08/48783 has satisfactorily completed research requirements for the award of Master of Science in Political Science (International Relations). The work embodied in this thesis is original and has not been submitted in part or in full for another degree of this or any other university, to the best of our knowledge: ---------------------------------- ------------------------------- Prof. Jonah Onuoha Ph.D Prof. E. O. Ezeani, Ph.D (Supervisor) (Head of Department) ---------------------------------- ------------------------------- External Examiner Dean iii DEDICATION To my brother Reverend Father, Prof. Ben, Ejide who inspired me iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The completion of this project report is due to the contribution of people too numerous to mention. However, I must thank my husband for his patience, understanding, prayers and financial support . I have benefited greatly from the assistance of my supervisor, Prof. Jonah Onuoha Ph.D., who expertly supervised this study. I am also grateful to the academic staff of the Department of Political Science, especially Prof. Ikejiani-Clark who encouraged and offered useful suggestions to me during the period of this programme. -

The Center for Research Libraries Scans to Provide Digital Delivery of Its Holdings

The Center for Research Libraries scans to provide digital delivery of its holdings. In some cases problems with the quality of the original document or microfilm reproduction may result in a lower quality scan, but it will be legible. In some cases pages may be damaged or missing. Files include OCR (machine searchable text) when the quality of the scan and the language or format of the text allows. If preferred, you may request a loan by contacting Center for Research Libraries through your Interlibrary Loan Office. Rights and usage Materials digitized by the Center for Research Libraries are intended for the personal educational and research use of students, scholars, and other researchers of the CRL member community. Copyrighted images and texts may not to be reproduced, displayed, distributed, broadcast, or downloaded for other purposes without the expressed, written permission of the copyright owner. Center for Research Libraries Identifier: f-n-000001 Downloaded on: Jun 15, 2017 5:03:23 PM r:; • lifgSit ■ » Federal RepubUc of Nigeria Official Gazette No. 36 Lagos - 12th July, 1973 Vol. 60 CONTENTS Page Page Movements • e . 1018-26 Establishment of Denton StreetPostal Agency, Ebute Metta ■ 4 • • » ■ e 1029 Yaba College of Tec^ology—Appointment (States Representatives of Coun^) Notice 1072 «« «« «a •• a, aa lyin Postal Agency—^Introduction of Savings 1026 Bank Fadlities 1030 Yaba College of Technology—Appointment Loss of Local Purchase Orders .. 1030 (States Representatives of Coun^) Notice 1973 .. .. 1626 Loss of local Purchase Order Booklet .. 1030 Applications under Trade Unions Act Cap. Loss of Payable Orders .. 1030 200 Laws of the Federation of Nigeria and Federal Government Bursary Scheme for the Lagos 1958 • • . -

2013 IPAI Convention in Houston July 25 — 28, 2013

2013 IPAI Convention in Houston July 25 — 28, 2013 Pa ge 2 www.ipaiinc.org Volume 1, Issue 1 OKO & ASSOCIATES LAW FIRM ATTORNEYS & COUNSELORS AT LAW High Chief, Atty. Chuck & Lolo Ijeoma Oko with children Martha, Victor, Chiamaka and Joseph Oko. The entire Oko family and staff of Oko & Associates Law Firm congratulate Igbere people in Diaspora on the forth coming IPAI Convention. Call us for All Your Legal Needs ! USA. OFFICES NIGERIA OFFICE 7324 S. W. Freeway, Suite 202 380 Lexington Avenue, 17th 62 Okilton St., off Ada George Houston, TX 77074 Floor Port Harcourt, Rivers State, Tel: (713) 773-4887 New York, NY 10168 Nigeria Fax: (713) 773-1140 TEL: (600) 300-9971 Tel: (0810) 777-8700 EMAIL: [email protected] EMAIL: [email protected] Www.okolawfirm.com Editor’s Note Welcome to the third edition of the convention magazine after Igbere Progressive Association International (IPAI) upgraded from program brochure to a biennial magazine. The aim is to expand our global reach by providing opportunity for Igbere people across the world to express their ideas, share their knowledge and expertise and support the develop- ment of Igbere Community. We solicited from the general public to support the 2013 IPAI Convention by plac- ing an Ad on this event program magazine. Thanks to the generosity of our members and friends who responded to the solicitation to support IPAI in this way. To those who could not respond, we believe you would have better reasons to do so in subsequent editions. However, we pray that God would provide for those who wanted to place an Ad but could not do so due to financial reasons, and at the same time bless and multiply the financial re- sources of those who made this extraordinary sacrifice to donate to IPAI in this way.