Philippe Sollers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phd Thesis the Anglo-American Reception of Georges Bataille

1 Eugene John Brennan PhD thesis The Anglo-American Reception of Georges Bataille: Readings in Theory and Popular Culture University of London Institute in Paris 2 I, Eugene John Brennan, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Signed: Eugene Brennan Date: 3 Acknowledgements This thesis was written with the support of the University of London Institute in Paris (ULIP). Thanks to Dr. Anna-Louis Milne and Professor Andrew Hussey for their supervision at different stages of the project. A special thanks to ULIP Librarian Erica Burnham, as well as Claire Miller and the ULIP administrative staff. Thanks to my postgraduate colleagues Russell Williams, Katie Tidmash and Alastair Hemmens for their support and comradery, as well as my colleagues at Université Paris 13. I would also like to thank Karl Whitney. This thesis was written with the invaluable encouragement and support of my family. Thanks to my parents, Eugene and Bernadette Brennan, as well as Aoife and Tony. 4 Thesis abstract The work of Georges Bataille is marked by extreme paradoxes, resistance to systemization, and conscious subversion of authorship. The inherent contradictions and interdisciplinary scope of his work have given rise to many different versions of ‘Bataille’. However one common feature to the many different readings is his status as a marginal figure, whose work is used to challenge existing intellectual orthodoxies. This thesis thus examines the reception of Bataille in the Anglophone world by focusing on how the marginality of his work has been interpreted within a number of key intellectual scenes. -

Reading Houellebecq and His Fictions

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2018 Reading Houellebecq And His Fictions Sterling Kouri University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Recommended Citation Kouri, Sterling, "Reading Houellebecq And His Fictions" (2018). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 3140. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3140 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3140 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Reading Houellebecq And His Fictions Abstract This dissertation explores the role of the author in literary criticism through the polarizing protagonist of contemporary French literature, Michel Houellebecq, whose novels have been both consecrated by France’s most prestigious literary prizes and mired in controversies. The polemics defining Houellebecq’s literary career fundamentally concern the blurring of lines between the author’s provocative public persona and his work. Amateur and professional readers alike often assimilate the public author, the implied author and his characters, disregarding the inherent heteroglossia of the novel and reducing Houellebecq’s works to thesis novels necessarily expressing the private opinions and prejudices of the author. This thesis explores an alternative approach to Houellebecq and his novels. Rather than employing the author’s public figure to read his novels, I proceed in precisely the opposite -

19Th and 20Th Century French Exoticism

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2004 19th and 20th century French exoticism: Pierre Loti, Louis-Ferdinand Céliné , Michel Leiris, and Simone Schwarz-Bart Robin Anita White Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the French and Francophone Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation White, Robin Anita, "19th and 20th century French exoticism: Pierre Loti, Louis-Ferdinand Céĺ ine, Michel Leiris, and Simone Schwarz-Bart" (2004). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2593. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2593 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. 19TH CENTURY AND 20TH CENTURY FRENCH EXOTICISM: PIERRE LOTI, LOUIS-FERDINAND CÉLINE, MICHEL LEIRIS, AND SIMONE SCHWARZ-BART A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of French Studies by Robin Anita White B.A. The Evergreen State College, 1991 Master of Arts Louisiana State University, 1999 August 2004 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This work is dedicated to my family and friends who lent me encouragement during my studies. They include my parents, Joe and Delsa, my brother and sister-in-law, and many others. I would like to express gratitude for the help I received from the Department of French Studies at LSU, in particular, Dr. -

Issue29 V5 Lineonline.Pdf

line http://americanbookreview.org ON Amber Dermont reviews Stephanie Fiorelli, Adam Koehler, line and Andrew Palmer, eds. AVER Y : Matthew Roberson reviews AN ANTHOLOG Y O F Fabrice Rozié, Esther Allen, and Guy Walter, eds. NE W FICTION Avery House Press AS YOU WERE Say ING : AMERIC A N WRITERS RESPOND TO “The great pleasure is in seeing THEIR FRENCH CONTEMPOR A RIES how the short fiction tradition is built upon, skewed, and subverted.” Dalkey Archive Press “As You Were Saying is a successful adventure in illustrating the Gabriel Cutrufello reviews unpredictable pleasures of encounter, Richard Katrovas dialogue, and connection.” THE YE A RS O F SM A SHING BRICKS : AN ANECDOT A L MEMOIR Bruce Holsapple reviews Carnegie Mellon University Press Philip Whalen; Michael Rothenberg, ed. “Katrovas at times seems to be dressing up over-sentimentalized THE COLLECTED POEMS O F memories of a painful young PHILIP WH A LEN adulthood with seemingly profound observations.” Wesleyan University Press “This poet is a master in the use of self-regard.” Stephen Burn reviews J. Peder Zane, ed. THE TOP TEN : WRITERS PICK THEIR Sam Truitt reviews Hannah Weiner; FA VORITE BOOKS Patrick F. Durgin, ed. Norton HA NN A H WEINER ’S “With the right writer, the list can OPEN HOUSE be a revealing window on to their Kenning Editions formative influences.” “A great boon of Hannah Weiner’s Open House lies in gathering her career-wide formal inflections in one place for the first time.” The Human Line Marilyn Kallet reviews ELLEN BASS Ellen Bass THE HUM A N LINE Kirby Olson reviews Copper Canyon Press Tony Trigilio “The Human Line is a ALLEN GINSBERG ’S well-made prayer for peace UDDHIST OETICS B P in the guise of art.” Southern Illinois University Press “Ginsberg’s aggression toward Buddhism needs to be carefully positioned when we think of Ginsberg as a ‘Buddhist.’” LineOnLine announces reviews abr featured exclusively on ABR’s website. -

Rewriting the Twentieth-Century French Literary Right: Translation, Ideology, and Literary History

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses Dissertations and Theses March 2017 Rewriting the Twentieth-century French Literary Right: Translation, Ideology, and Literary History Marcus Khoury University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/masters_theses_2 Part of the French and Francophone Literature Commons, and the Translation Studies Commons Recommended Citation Khoury, Marcus, "Rewriting the Twentieth-century French Literary Right: Translation, Ideology, and Literary History" (2017). Masters Theses. 469. https://doi.org/10.7275/9468894 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/masters_theses_2/469 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REWRITING THE TWENTIETH-CENTURY FRENCH LITERARY RIGHT: TRANSLATION, IDEOLOGY, AND LITERARY HISTORY A Thesis Presented by MARCUS KHOURY Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS February 2017 Comparative Literature Translation Studies Track Department of Languages, Literatures, and Cultures © Copyright by Marcus Khoury 2017 All Rights Reserved REWRITING THE TWENTIETH-CENTURY FRENCH LITERARY RIGHT: TRANSLATION, IDEOLOGY, AND LITERARY HISTORY A Thesis -

In the Winter of 1967 a Special Issue of the French Literary Review Tel Quel Was Published Devoted Entirely to the Writing of the Marquis De Sade

296 French Theory and American Art Blanchot, Tel Quel and the Formation of a Sadean 297 In the winter of 1967 a special issue of the French literary review Tel Quel was published devoted entirely to the writing of the Marquis de Sade. 1 Bringing together the commentary of both those central to the review’s project and those with similar concerns, this publication formed one of a series of sig- nificant moments in the reception and so-called rehabilitation of Sade’s work amongst a new generation of post-Second World War writers and intellectuals. In the pages of Tel Quel one sees a confluence of theoretical and literary concerns invested in Sade’s oeuvre—as Patrick French says, Sade’s work was “the principle focus” of the review’s enquiry into “the relation of sex to writing.” 2 This investment in the figure of the writer was related to, and followed, the efforts of the publisher Jean- Jacques Pauvert, who during the 1950s and 1960s, in a direct challenge to the laws on obscenity in France, made available the author’s complete body of work. New York’s maverick pub- lishers Grove Press shortly followed suit, publishing Justine, Philosophy in the Bedroom, & Other Writings in English in 1965, and a series of other volumes thereafter. These publications were accompanied by extensive essays by an earlier generation of Blanchot, Tel Quel and the Benjamin Greenman French thinkers, including (amongst others) Maurice Blanchot, Formation of a Sadean Aesthetic whose essay was the first translation of his work into English. in the Work of Vito Acconci It was to the theorization of Sade’s work by this earlier genera- tion of intellectuals that both contributors to Tel Quel and the American artist Vito Acconci were responding in the late 1960s. -

October-2017.Pdf

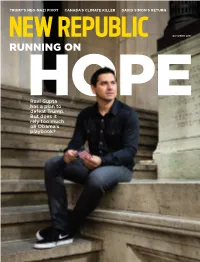

Inside stories of how activist staffers countered corporate lobbies “A wonderful read.” — ROBERT REICH “ Witty and penetrating…” — NORMAN ORNSTEIN “ This book is the story of a public servant … and his fellow activist staffers, whose valiant work on consumer protection has helped millions of Americans.” — RALPH NADER “A lively and thought- provoking book…” — JAMES A. THURBER “ This may be the most important political book written about our current political dysfunction…” — MATT MYERS Available now in jacketed cloth & ebook formats. Visit us at www.vanderbiltuniversitypress.com. contents OCTOBER 2017 UP FRONT 6 The New Fight for Labor Rights 18 To survive, the labor movement needs to rethink its strategy. BY RACHEL M. COHEN 8 Losing Hearts and Minds How Trump quietly gutted a program to combat extremism. BY BENJAMIN POWERS 9 The Trump Tweetometer A look inside the president’s mind, based on his first seven months of tweets. 10 The Next Standing Rock Why is Canada green-lighting a pipeline that could kill the climate? BY BEN ADLER 12 Art of the Steal How Trump’s self-dealing helped make his book a best-seller. BY ALEX SHEPHARD COLUMNS 14 Deadbeat Democrats How Bill Clinton set the stage for the GOP’s war on the poor. BY BRYCE COVERT Lauren Underwood, 16 a nurse from Illinois, Redoing the Electoral Math is a candidate for Congress. It will take more than demographics to save the Democrats. BY JOHN B. JUDIS Running on Hope REVIEW 46 Rules for Radicals A new group of Obama aides aims to take down Trump. The right-wing economist who rigged But can Democrats win without a unified message? democracy for the rich. -

Roger Celestin 346 West 48Th Street the University of Connecticut Apt

CURRICULUM VITAE Roger Celestin 346 West 48th Street The University of Connecticut Apt. 3E Department of Literatures, Cultures and Languages New York, NY 10036 Storrs, CT 06269-1057 TEL. (860 486 3313/Email: [email protected] EDUCATION GRADUATE 1989 The Graduate Center of the City University of New York; Ph.D. in Comparative Literature/French. 1979 Sorbonne, Université de Paris IV; Diplôme d'Etudes Approfondies (ABD) in Anglo-American Literature and Civilization. 1978 Sorbonne; Maîtrise, summa cum laude in Anglo-American Literature and Civilization 1977 Institut d'Etudes Politiques de Paris; Diplôme de l'Institut. Major: International Relations. 1977 Centre de Formation des Journalistes de Paris. Diplôme du Centre. Specializations: news agency and newspaper reporting. UNDERGRADUATE 1976 Sorbonne; License ès lettres. 1974 Queens College, City University of New York. B.A. cum laude in French and Political Science. BOOKS •France 1851 to the Present: Universalism in Crisis. Palgrave-Saint Martin's Press. 2007. Co- authored with Eliane DalMolin, University of Connecticut. •Beyond French Feminisms: Debates on Women, Politics and Culture in France. 1980-2001. Palgrave-Saint Martin's Press. 2002. Co-edited with Eliane DalMolin, University of Connecticut, and Isabelle de Courtivron, MIT. •From Cannibals to Radicals: Figures and Limits of Exoticism; 1996, University of Minnesota Press. Roger Célestin Page 1 EDITED JOURNAL VOLUMES •Founding editor and present editor of Contemporary French & Francophone Studies: SITES, which publishes scholarly articles exclusively in the field of 20th-century and contemporary French and Francophone literatures and cultures, as well as fiction and poetry. Each issue of the journal is devoted to a single theme; at first two issues per year (250 pages per issue), published by Routledge). -

Sade-Omizing Sexuality: Deconstructing the Gender Binary Through the Sadian Sexual Predator

SADE-OMIZING SEXUALITY: DECONSTRUCTING THE GENDER BINARY THROUGH THE SADIAN SEXUAL PREDATOR by Jennifer Lee Lawrence BA, West Virginia University, 2001 MA, West Virginia University, 2004 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2013 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Jennifer Lee Lawrence It was defended on March 22, 2013 and approved by Giuseppina Mecchia, PhD, Associate Professor, French and Italian Clark Muenzer, PhD, Associate Professor, German Francesca Savoia, PhD, Professor, French and Italian Dissertation Advisor: Todd Reeser, PhD, Professor, French and Italian ii Copyright © by Jennifer Lee Lawrence 2013 iii SADE-OMIZING SEXUALITY: DECONSTRUCTING THE GENDER BINARY THROUGH THE SADIAN SEXUAL PREDATOR Jennifer Lee Lawrence, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2013 The Marquis de Sade became famous, or infamous depending on one’s perspective, for the ferocious depictions of sexual predation which are found throughout his literary works, and consequently, the character of the sexual predator is indispensable to understanding the author’s philosophical standpoint. For Sade, the laws of nature determine the sex of the individual, but they also require him or her to satisfy a set of physical needs which reject the masculine/feminine binary as often as they embrace it. This blurring of the lines between masculinity and femininity is thus characteristic of the Sadian sexual predator who must constantly seek satisfaction for his needs regardless of social and religious constraints on his behavior and on the sex of his victim. -

The Tel Quel Reader

The Tel Quel Reader Patrick Ffrench and Roland-Francois Lack Editeur : Routledge; Édition : annotated edition (19 fév. 1998) Langue : Anglais ISBN-10 : 0415157137 ISBN-13 : 978-0415157131 288 pages Table des matières Sur le livre Préface Histoire chronologique de Tel Quel Table des matières Preface Acknowledgements Introduction PATRICK ffRENCH RONALD-FRANCOIS LACK Chronological history of Tel Quel PART I Science 1 Division of the assembly TEL QUEL 2 Towards a semiology of paragrams JULIA KRISTEVA 3 Marx and the inscription of labour JEAN-JOSEPH GOUX 4 Freud and `literary creation' JEAN-LOUIS BAUDRY PART II Literature 5 Distance, aspect, origin MICHEL FOUCAULT 6 The readability of Sade MARCELIN PLEYNET 7 The Bataille act PHILIPPE SOLLERS 8 The subject in process JULIA KRISTEVA 1 PART III Art 9 Chromatic painting: theorem written through painting MARC DEVADE 10 Heavenly Glory MARCELIN PLEYNET 11 Thetic `madness' MARCELIN PLEYNET 12 The American body: notes on the new experimental theatre GUY SCARPETTA 13 Paradis PHILIPPE SOLLERS PART IV Dissemination Dissemination PATRICK ffRENCH ROLAND-FRANCOIS LACK 14 Responses: interview with Tel Quel ROLAND BARTHES Bibliography Index Sur le livre From Library Journal Excerpted from the French journal Tel Quel (1960-82) and ably translated by two lecturers in French at University College, London, these articles demonstrate French poststructuralist radical literary theory as practiced in France during the 1960s and 1970s by some of its major proponents, e.g., Julia Kristeva, Michel Foucault, Philippe Sollers, Marc Devade, Marcelin Pleynet, and Roland Barthes. The articles explore literature and culture, gender, film, semiotics, and psychoanalysis. Critics have detected a progressive movement in the journal itself from literature tel quel, "such as it is," toward the avant- garde and toward a scientific analysis of literature. -

The Evolution of the French Avant-Garde from Italian Futurism, to Surrealism, to Situationism, to the Writers of the Literary Journal Tel Quel

A CHANGING OF THE GUARD: THE EVOLUTION OF THE FRENCH AVANT-GARDE FROM ITALIAN FUTURISM, TO SURREALISM, TO SITUATIONISM, TO THE WRITERS OF THE LITERARY JOURNAL TEL QUEL DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Mary Laura Papalas, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2008 Dissertation Committee: Professor Jean-François Fourny, Adviser Approved by Professor Charles Klopp Professor Judith Mayne _______________________________ Professor Karlis Racevskis Adviser Graduate Program in French & Italian Copyright by Mary Laura Papalas May 2008 ABSTRACT The avant-garde is an aesthetic movement that spanned the twentieth century. It is made up of writers and artists that rebelled against art and against society in a concerted effort to improve both, and their relationship to one another. Four avant-garde groups, the Futurists, the Surrealists, the Situationists, and the writers of the journal Tel Quel , significantly contributed to the avant-garde movement and provided perspective into whether that movement can exist in the twenty first century. The first Futurist Manifesto , published in the French newspaper Le Figaro in 1909 by Philippo Tommaso Marinetti, instigated the avant-garde wave that would be taken up after the Great War by the Surrealists, whose first 1924 Manifeste du Surréalisme echoed the Futurist message of embracing modern life and change through art. The Surrealists, however, focused more on Marxism and psychoanalysis, developing ideas about life and art that combined these two ideologies in order to link the improvement of society with the unconscious individual experience. The Situationists, whose group formed in 1957, took up the themes of social revolution and freedom of the unconscious, developing a method for creating situations that were conducive to both of these things. -

Glenn Gould - Excerpt from Sollers - Peacock Journal

Armine Kotin Mortimer - Glenn Gould - Excerpt from Sollers - Peacock Journal Armine Kotin Mortimer “Glenn Gould” An excerpt from A Permanent Passion By Philippe Sollers Translated by Armine Kotin Mortimer Summer evenings are especially magical after the closing of the park gates. The sky above the long, shining avenues is dark blue. The blackbirds are singing in the flowering chestnut trees. Clara is staying in Paris, we tour the city. Dora has appointments in Switzerland and comes back. With Clara, I shut myself in to listen to all the recordings Glenn Gould made of Bach. She knows them by heart, but I want to see how she herself hears the various entrances. We are barefoot, we float on the parquet floor . Gould represents the introduction of metaphysics into recordings . I show Clara a passage from a novel by Thomas Bernhard, The Loser: http://peacockjournal.com/armine-kotin-mortimer-glenn-gould-excerpt-sollers/[10/18/2016 4:06:21 PM] Armine Kotin Mortimer - Glenn Gould - Excerpt from Sollers - Peacock Journal “Hunched over his Steinway, he looked like a cripple, that’s how the entire musical world knows him, but this entire musical world is prey to a total misconception, I thought. Glenn is portrayed everywhere as a cripple and a weakling, as the transcendent artist his fans can accept only with his infirmity and the hypersensitivity that goes along with his infirmity, but actually he was an athletic type, much stronger than Wertheimer and me put together, we realized that at once when he went out to chop down an ash tree with his own hands, an ash tree in front of his window, which, as he put it, obstructed his playing.