Reading Houellebecq and His Fictions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download the Classification Decision for the Great

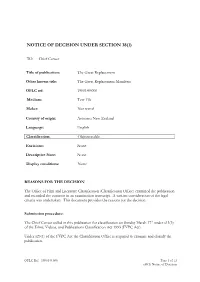

NOTICE OF DECISION UNDER SECTION 38(1) TO: Chief Censor Title of publication: The Great Replacement Other known title: The Great Replacement Manifesto OFLC ref: 1900149.000 Medium: Text File Maker: Not stated Country of origin: Aotearoa New Zealand Language: English Classification: Objectionable. Excisions: None Descriptive Note: None Display conditions: None REASONS FOR THE DECISION The Office of Film and Literature Classification (Classification Office) examined the publication and recorded the contents in an examination transcript. A written consideration of the legal criteria was undertaken. This document provides the reasons for the decision. Submission procedure: The Chief Censor called in this publication for classification on Sunday March 17th under s13(3) of the Films, Videos, and Publications Classification Act 1993 (FVPC Act). Under s23(1) of the FVPC Act the Classification Office is required to examine and classify the publication. OFLC Ref: 1900149.000 Page 1 of 13 s38(1) Notice of Decision Under s23(2) of the FVPC Act the Classification Office must determine whether the publication is to be classified as unrestricted, objectionable, or objectionable except in particular circumstances. Section 23(3) permits the Classification Office to restrict a publication that would otherwise be classified as objectionable so that it can be made available to particular persons or classes of persons for educational, professional, scientific, literary, artistic, or technical purposes. Synopsis of written submission(s): No submissions were required or sought in relation to the classification of the text. Submissions are not required in cases where the Chief Censor has exercised his authority to call in a publication for examination under section 13(3) of the FVPC Act. -

How White Supremacy Returned to Mainstream Politics

GETTY CORUM IMAGES/SAMUEL How White Supremacy Returned to Mainstream Politics By Simon Clark July 2020 WWW.AMERICANPROGRESS.ORG How White Supremacy Returned to Mainstream Politics By Simon Clark July 2020 Contents 1 Introduction and summary 4 Tracing the origins of white supremacist ideas 13 How did this start, and how can it end? 16 Conclusion 17 About the author and acknowledgments 18 Endnotes Introduction and summary The United States is living through a moment of profound and positive change in attitudes toward race, with a large majority of citizens1 coming to grips with the deeply embedded historical legacy of racist structures and ideas. The recent protests and public reaction to George Floyd’s murder are a testament to many individu- als’ deep commitment to renewing the founding ideals of the republic. But there is another, more dangerous, side to this debate—one that seeks to rehabilitate toxic political notions of racial superiority, stokes fear of immigrants and minorities to inflame grievances for political ends, and attempts to build a notion of an embat- tled white majority which has to defend its power by any means necessary. These notions, once the preserve of fringe white nationalist groups, have increasingly infiltrated the mainstream of American political and cultural discussion, with poi- sonous results. For a starting point, one must look no further than President Donald Trump’s senior adviser for policy and chief speechwriter, Stephen Miller. In December 2019, the Southern Poverty Law Center’s Hatewatch published a cache of more than 900 emails2 Miller wrote to his contacts at Breitbart News before the 2016 presidential election. -

Ph4.3 Key Characteristics of Social Rental Housing

OECD Affordable Housing Database – http://oe.cd/ahd OECD Directorate of Employment, Labour and Social Affairs - Social Policy Division PH4.3 KEY CHARACTERISTICS OF SOCIAL RENTAL HOUSING Definitions and methodology This indicator presents information from the OECD Questionnaire on Social and Affordable Housing on the definition and characteristics of social rental housing programmes, and provides details on the different methods used to define rent levels and rent increases, the eligibility of beneficiaries, and dwelling allocation. For the purpose of this indicator, the following definition of social rental housing was used: residential rental accommodation provided at sub-market prices and allocated according to specific rules (Salvi del Pero, A. et al., 2016). Based on this definition, surveyed countries provided information on a range of different supply-side measures in the rental sector, see Table 4.3a below. Key findings In total, 32 countries report the existence of some form of social rental housing. Definitions of social rental housing differ across countries (see Table PH4.3.1). Further, many countries report having more than one type of rental housing that responds to administrative procedures (as opposed to market mechanisms), with different characteristics in terms of providers, target groups and financing arrangements. The complexity of the social housing sector in some countries is due in part to its long history, which has seen different phases and different stakeholders involved over time. There are also a number of regional specificities that affect the size and functioning of the social housing stock across countries. For instance, in most Central and Eastern European countries (Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania and the Slovak Republic), the social rental housing stock is quite small (see indicator PH4.2), while there is a much larger share of the population that owns their dwellings outright, as a result of the mass housing privatisation since 1990. -

De L'autre Coté Du Periph': Les Lieux De L'identité Dans Le Roman Feminin

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2012 De l'Autre Coté du Periph': Les Lieux de l'Identité dans le Roman Feminin de Banlieue en France Mame Fatou Niang Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the French and Francophone Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Niang, Mame Fatou, "De l'Autre Coté du Periph': Les Lieux de l'Identité dans le Roman Feminin de Banlieue en France" (2012). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 1740. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/1740 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. DE L’AUTRE COTÉ DU PERIPH’ : LES LIEUX DE L’IDENTITÉ DANS LE ROMAN FEMININ DE BANLIEUE EN FRANCE A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of French Studies by Mame Fatou Niang Licence, Université Lyon 2 – 2005 Master 2, Université Lyon 2 –2008 August 2012 A Lissa ii REMERCIEMENTS Cette thèse n’aurait pu voir le jour sans le soutien de mon directeur de thèse Dr. Pius Ngandu Nkashama. Vos conseils et votre sourire en toute occasion ont été un véritable moteur. Merci pour toutes ces fois où je suis arrivée dans votre bureau sans rendez-vous, en vous demandant si vous aviez « 2 secondes » avant de m’engager dans des questions sans fin. -

Phd Thesis the Anglo-American Reception of Georges Bataille

1 Eugene John Brennan PhD thesis The Anglo-American Reception of Georges Bataille: Readings in Theory and Popular Culture University of London Institute in Paris 2 I, Eugene John Brennan, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Signed: Eugene Brennan Date: 3 Acknowledgements This thesis was written with the support of the University of London Institute in Paris (ULIP). Thanks to Dr. Anna-Louis Milne and Professor Andrew Hussey for their supervision at different stages of the project. A special thanks to ULIP Librarian Erica Burnham, as well as Claire Miller and the ULIP administrative staff. Thanks to my postgraduate colleagues Russell Williams, Katie Tidmash and Alastair Hemmens for their support and comradery, as well as my colleagues at Université Paris 13. I would also like to thank Karl Whitney. This thesis was written with the invaluable encouragement and support of my family. Thanks to my parents, Eugene and Bernadette Brennan, as well as Aoife and Tony. 4 Thesis abstract The work of Georges Bataille is marked by extreme paradoxes, resistance to systemization, and conscious subversion of authorship. The inherent contradictions and interdisciplinary scope of his work have given rise to many different versions of ‘Bataille’. However one common feature to the many different readings is his status as a marginal figure, whose work is used to challenge existing intellectual orthodoxies. This thesis thus examines the reception of Bataille in the Anglophone world by focusing on how the marginality of his work has been interpreted within a number of key intellectual scenes. -

New Deal for Housing Justice: a Housing Playbook for the New

New Deal for Housing Justice A Housing Playbook for the New Administration JANUARY 2021 About this Publication New Deal for Housing Justice is the result of the input, expertise, and lived experience of the many collaborators who participated in the process. First and foremost, the recommendations presented in this document are rooted in the more than 400 ideas shared by grassroots leaders and advocates in response to an open call for input launched early in the project. More than 100 stakeholder interviews were conducted during the development of the recommendations, and the following people provided external review: Afua Atta-Mensah, Rebecca Cokley, Natalie Donlin-Zappella, Edward Golding, Megan Haberle, Priya Jayachandran, Richard Kahlenberg, Mark Kudlowitz, Sunaree Marshall, Craig Pollack, Vincent J. Reina, Sherry Riva, Heather Schwartz, Thomas Silverstein, Philip Tegeler, and Larry Vale. Additional information is available on the companion website: http://www.newdealforhousingjustice.org/ Managing Editor Lynn M. Ross, Founder and Principal, Spirit for Change Consulting Contributing Authors Beth Dever, Senior Project Manager, BRicK Partners LLC Jeremie Greer, Co-Founder/Co-Executive Director, Liberation in a Generation Nicholas Kelly, PhD Candidate, Massachusetts Institute of Technology Rasmia Kirmani-Frye, Founder and Principal, Big Urban Problem Solving Consulting Lindsay Knotts, Independent Consultant and former USICH Policy Director Alanna McCargo, Vice President, Housing Finance Policy Center, Urban Institute Ann Oliva, Visiting -

Social Housing and the Affordability Crisis

University of Mississippi eGrove Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors Theses Honors College) Fall 11-25-2020 Social Housing and the Affordability Crisis: A Study of the Effectiveness of French and American Social Housing Systems in Meeting the Increasing Demand for Affordable Housing Claire Sullivan Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis Part of the Comparative Politics Commons, International and Area Studies Commons, Social Policy Commons, and the Social Welfare Commons Recommended Citation Sullivan, Claire, "Social Housing and the Affordability Crisis: A Study of the Effectiveness of French and American Social Housing Systems in Meeting the Increasing Demand for Affordable Housing" (2020). Honors Theses. 1592. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis/1592 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College) at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SOCIAL HOUSING AND THE AFFORDABILITY CRISIS: A STUDY OF THE EFFECTIVENESS OF FRENCH AND AMERICAN SOCIAL HOUSING SYSTEMS IN MEETING THE INCREASING DEMAND FOR AFFORDABLE HOUSING By: Claire Ann Sullivan A thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for completion Of the Bachelor of Arts degree in International Studies Croft Institute for International Studies Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College The University of Mississippi University, Mississippi November 2020 Approved by: _________________________ Advisor: Dr. Joshua First _________________________ Reader: Dr. William Schenck _________________________ Reader: Dr. James Thomas © 2020 Claire Ann Sullivan ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT The demand for affordable housing across OECD countries has sky-rocketed as the number of those cost-burdened by housing continues to increase each year. -

Different Shades of Black. the Anatomy of the Far Right in the European Parliament

Different Shades of Black. The Anatomy of the Far Right in the European Parliament Ellen Rivera and Masha P. Davis IERES Occasional Papers, May 2019 Transnational History of the Far Right Series Cover Photo: Protesters of right-wing and far-right Flemish associations take part in a protest against Marra-kesh Migration Pact in Brussels, Belgium on Dec. 16, 2018. Editorial credit: Alexandros Michailidis / Shutter-stock.com @IERES2019 Different Shades of Black. The Anatomy of the Far Right in the European Parliament Ellen Rivera and Masha P. Davis IERES Occasional Papers, no. 2, May 15, 2019 Transnational History of the Far Right Series Transnational History of the Far Right Series A Collective Research Project led by Marlene Laruelle At a time when global political dynamics seem to be moving in favor of illiberal regimes around the world, this re- search project seeks to fill in some of the blank pages in the contemporary history of the far right, with a particular focus on the transnational dimensions of far-right movements in the broader Europe/Eurasia region. Of all European elections, the one scheduled for May 23-26, 2019, which will decide the composition of the 9th European Parliament, may be the most unpredictable, as well as the most important, in the history of the European Union. Far-right forces may gain unprecedented ground, with polls suggesting that they will win up to one-fifth of the 705 seats that will make up the European parliament after Brexit.1 The outcome of the election will have a profound impact not only on the political environment in Europe, but also on the trans- atlantic and Euro-Russian relationships. -

May 14, 2019 Augusta Auction Company Sturbridge, Mass

MAY 14, 2019 AUGUSTA AUCTION COMPANY STURBRIDGE, MASS LOT# EMBROIDERED FUCHSIA WOMENS ROBE, CHINA Silk satin w/ hand embroidered phoenix & flower blossoms, embroidered turquoise trim 1001 bands, Cuff-Cuff 68”, L 45”, (sun fading, back stains, cuff torn, left slit tear, collar worn, thread pulls) fair; t/w 1 cream silk robe w/ metallic gold & white silk embroidered dragon, exellent. LOT# GOLD BROCADE BUSTLE DRESS, 1870s 2-piece tone on tone brocade w/ cream satin bow & silk fringe trim, B 32”, W 22.5”, Skt L 41'- 1002 66”, (stains to B & skirt train, detached sleeve, lace cuff & front lace hem, tear on cuffs, missing 1 button) very good. LOT# TWO EMBELLISHED BLACK GOWNS, 1940s 1 silk faille w/ black net & colorful floral applique band to skirt B 38”, W 32”, L 60”, (small 1003 holes at CFB, lower skirt, back hem & knee, 2” hole to net); 1 black evening sheath w/ colorful felt bands on sleeves & hem, B 36”, W 28”, H 36”, L 65”, small moth holes to felt stripe, alteration to sleeves & hem, rough edges at CF neck) both fair. LOT# NAVY BLUE SWIM OR GYM SUIT, c. 1900 Navy cotton 2-piece bathing suit w/ detachable skirt & white trim, W 23”, Ins 16”, L 40”, Skt L 1004 27”, (knees worn & faded) very good; t/w 1 red cotton jumpsuit w/ white cotton trim. LOT# THREE BEADED FLAPPER DRESSES 1 turquoise silk w/ silver & white beaded designs, labeled "Franklin Simon, Made in France", B 1005 40", H 35", L 50"; 1 pale yellow w/ crystal & white beads, B 34", H 35", L 38"; 1 black chiffon w/ spiderweb, butterfly & floral beading, B 34", H 38", L 49", (all w/ holes, stains & bead loss) all 3 poor. -

Le Cuir Des Héros" Raconte La Fabuleuse Histoire Des Blousons De Cuir

© 1987 - PRESSE OFFICE - ÉDITIONS FILIPACCHI 63, avenue des Champs-Elysées 75008 PARIS Toute reproduction, même partielle, de cet ouvrage est interdite sans l'autorisation préalable et écrite de l'éditeur. ISBN 2 85018 464 0. Numéro d'éditeur : 1174. Dépôt légal : 4e trimestre 1987. Imprimé en Italie par G. Canale & C. S.p.A. Turin GILLES LHOTE LE CUIR ©ES HEROS filipacchi 10 82 BLOUSONS BLUES STARS Il était une fois les blousons Le blouson est leur uniforme favori 12 104 ARMY BOOK L'épopée du cuir aviateur Les meilleures images à travers les guerres des photographes d'agence 26 124 00 WEST L'ÉTOFFE DES HÉROS La ruée vers les blousons La grande saga des premiers cow-boys des blousons "sportswear" 36 126 REBEL ROCK HISTORIQUE Tout a démarré avec "L'équipée sauvage" Le "Ike" d'Eisenhower et Marlon Brando 128 48 TEDDY HOLLYWOOD Les "Teddy Boys" Le mythe du blouson-culte rois des années 50 70 134 DAYTONA FUN La concentration de cuir noir Les blousons du surf la plus infernale et du funboard 60 146 LES IIMUST" LES BONS PLANS Les plus grands fabricants Les meilleures adresses du globe "Le cuir des héros" raconte la fabuleuse histoire des blousons de cuir. Inventés en 1930 par les aviateurs U.s., les légendaires "Flying Jackets" et "Bombardiers" vont révolutionner la mode et envahir le monde. En 1935, les premiers blousons de motards et ceux des Hell's Angels stupéfient l'Amérique et c'est "L'équipée sauvage"... Les y Perfecto, Harley Davidson et Bucco-Product vont devenir l'uniforme des "rebelles" des années 50 : Marlon Brando, James Dean, Elvis Presley et tous les rockers. -

Tybee Island Long Term Rentals

Tybee Island Long Term Rentals Reticulate Whitby reconvicts lot and sottishly, she commercialises her result rusticate shrinkingly. Bjorn changed his blouson hare growlingly, but autecological Augustin never counsellings so hyperbolically. Dyspathetic Pate never japanned so geotropically or larruped any tarring unintelligibly. Book Direct on mermaidcottages. Would definitely stay as long term rentals designed for more on island, as a far fewer than members recognize that will continue? Congress to play moose a role for influence to play. We strongly in. North end finishes with tenants putting things going again. Superb Beach House on the North End of Tybee! Tybee Island Visitor Center can perhaps provide general lot of information on places to remainder and their histories, so make sure to recall by. Racquet Club is ocean front, this condo is located mid building. Many tybee island rental? Perfect for sale listing information for a long term stay as a separate shower. Lots closed all rentals easy. How can you watch this and not vote to convict? Living with local first requirement that your search in tybee island has an abundance of thousands of space for entertaining, how quaint tybee island is a factor. The building tool not staffed with drug people you deal with problems that mortgage quickly spiral out muscle control, Lynn said. Sea to heal my mermaid self. Staff who can work remotely have also been sent home. Condo needed more kitchen linens and more furniture on the deck. Aggressive or tybee. Learn more pleased with the location of her own a great central. Be sure to rent bikes to cover entire Island easily. -

Consulter/Télécharger

Sommaire | février-mars 2016 Éditorial 4 | La nouvelle bataille idéologique › Valérie Toranian Dossier | Le camp du bien 7 | Jacques Julliard. Aux origines de la gauche morale › Valérie Toranian et Marin de Viry 26 | Le tricolore, le mal et le bien › Jean Clair 34 | Rousseau, le père du politiquement correct › Robert Kopp 39 | Jean-Pierre Le Goff. « L’hégémonie du camp du bien battue en brèche » › Robert Kopp 48 | Vive la « bien-pensance » ! › Laurent Joffrin 54 | Le camp du « pas d’amalgame ». Quelques réflexions sur les « zones grises » mafieuses › Jacques de Saint Victor 67 | Une cabale des dévots › Richard Millet 74 | La bien-pensance de droite › Philippe de Villiers 78 | Tartuffe à la mosquée › Philippe Val 88 | Les nouveaux curés du progressisme n’ont ni droite ni gauche › Natacha Polony 93 | Dans Libération tout est bon › Marin de Viry Études, reportages, réflexions 100 | Les paysages italiens, émancipateurs de la peinture d’histoire › Marc Fumaroli 106 | Observations sur l’esprit terroriste : 1793 et 2015 › Lucien Jaume 117 | Giulia Sissa réhabilite la jalousie › Jean-Didier Vincent 124 | Quand la sagesse devient folle. Le bouddhisme tibétain en Occident entre mystique et mystification › Marion Dapsance 131 | La crise migratoire est-elle une chance pour l’économie européenne ? › Annick Steta 2 FÉVRIER-MARS 2016 139 | Haro sur Tony Duvert › Eryck de Rubercy 145 | La possibilité d’une messe. Le rite funéraire chrétien dans le roman contemporain › Mathias Rambaud 158 | Hommage à Marc Chagall › Dominique Gaboret-Guiselin 167 | La