Center for Florida History Oral History Program

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oral History Interview – JFK#1, 07/30/1964 Administrative Information

C. Douglas Dillon Oral History Interview – JFK#1, 07/30/1964 Administrative Information Creator: C. Douglas Dillon Interviewer: Dixon Donnelley Date of Interview: July 30, 1964 Place of Interview: Washington, D.C. Length: 26 pages Biographical Note Dillon, Secretary of the Treasury (1961-1965) discusses his role as a Republican in JFK’s Administration and his personal relationship with JFK, among other issues. Access Open Usage Restrictions According to the deed of gift signed, February 26, 1965, copyright of these materials has been assigned to the United States Government. Users of these materials are advised to determine the copyright status of any document from which they wish to publish. Copyright The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be “used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research.” If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excesses of “fair use,” that user may be liable for copyright infringement. This institution reserves the right to refuse to accept a copying order if, in its judgment, fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law. The copyright law extends its protection to unpublished works from the moment of creation in a tangible form. Direct your questions concerning copyright to the reference staff. -

Personal History: Katharine Graham Free

FREE PERSONAL HISTORY: KATHARINE GRAHAM PDF Katharine Graham | 642 pages | 01 Apr 1998 | Random House USA Inc | 9780375701047 | English | New York, United States Personal History by Katharine Graham, Paperback | Barnes & Noble® Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Want to Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. Preview — Personal History by Katharine Graham. Personal History by Katharine Graham. In lieu of an unrevealing Famous-People-I-Have-Known autobiography, the owner of the Washington Post has chosen to be remarkably candid about the insecurities prompted by remote parents and a difficult marriage to the charismatic, manic- depressive Phil Graham, who ran the newspaper her father acquired. Katharine's account of her years as subservient daughter and wife is so In lieu of an unrevealing Famous-People-I-Have-Known autobiography, the owner Personal History: Katharine Graham the Washington Post has chosen to be remarkably candid about the insecurities prompted by remote parents and a difficult marriage to the charismatic, manic-depressive Phil Graham, who ran the newspaper her father acquired. Katharine's account of her years as subservient daughter and wife is so painful that by the time she finally asserts herself at the Post following Phil's suicide in more than halfway through the bookreaders will want to cheer. After that, Watergate is practically an anticlimax. Get A Copy. Paperbackpages. Published February 24th by Vintage first published More Details Original Title. -

Adrian Fisher Interview I

LYNDON BAINES JOHNSON LIBRARY ORAL HISTORY COLLECTION The LBJ Library Oral History Collection is composed primarily of interviews conducted for the Library by the University of Texas Oral History Project and the LBJ Library Oral History Project. In addition, some interviews were done for the Library under the auspices of the National Archives and the White House during the Johnson administration. Some of the Library's many oral history transcripts are available on the INTERNET. Individuals whose interviews appear on the INTERNET may have other interviews available on paper at the LBJ Library. Transcripts of oral history interviews may be consulted at the Library or lending copies may be borrowed by writing to the Interlibrary Loan Archivist, LBJ Library, 2313 Red River Street, Austin, Texas, 78705. ADRIAN S. FISHER ORAL HISTORY, INTERVIEW I PREFERRED CITATION For Internet Copy: Transcript, Adrian S. Fisher Oral History Interview I, 10/31/68, by Paige Mulhollan, Internet Copy, LBJ Library. For Electronic Copy on Diskette from the LBJ Library: Transcript, Adrian S. Fisher Oral History Interview I, 10/31/68, by Paige Mulhollan, Electronic Copy, LBJ Library. GENERAL SERVICES ADMINISTRATION NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS SERVICE Gift of Personal Statement By Adrian S. Fisher to the Lyndon Baines Johnson Library In accordance with Sec. 507 of the Federal Property and Administrative Services Act of 1949, as amended (44 U.S.C. 397) and regulations issued thereunder (41 CFR 101-10), I, Adrian S. Fisher, hereinafter referred to as the donor, hereby give, donate, and convey to the United States of America for eventual deposit in the proposed Lyndon Baines Johnson Library, and for administration therein by the authorities thereof, a tape and transcript of a personal statement approved by me and prepared for the purpose of deposit in the Lyndon Baines Johnson Library. -

Katharine Graham's Autobiography, Personal History Is a Retelling of a Tale of Two Cities

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by British Columbia's network of post-secondary digital repositories Katharine Graham's autobiography, Personal History is a retelling of A Tale of Two Cities. Graham was an owner and publisher of the Washington Post. She died last July, aged 84. Graham recounts a life filled with entertaining and influencing presidents, business leaders, and celebrities. Access to her world was largely constrained to rich American nobles. She affords fleeting glimpses of lower American classes across the chasm that separates hers from theirs. Graham’s life was centred around events defining Washington as a complex city state - a closed universe, but also the American political capital and a fulcrum of global events. She had remarkable friendships with exceptional people. She led a patrician's life launched by inherited wealth, but sustained by her intellect, resilience and terrier-like determination. Graham proved that women needn't be restricted to secondary roles as men rise to become the top dogs. Graham's father, a pup from a distinguished Jewish family, made a small fortune in California and on Wall Street between 1890 and 1916. Graham's mother was gentile and the daughter of a New York city lawyer. Katharine was raised on a manor by the Hudson River and in a large apartment in New York. She enjoyed an idyllic childhood interspersed with irritating episodes of anti-Semitism. Her wealth opened doors that for most of her contemporaries were forever locked regardless of their other personal attributes or potentials. -

What the Eulogists Didn't Tell You About Katie Graham and the {Post}

Click here for Full Issue of EIR Volume 28, Number 32, August 24, 2001 Book Review What the Eulogists Didn’t Tell You About Katie Graham and the Post by Edward Spannaus A most useful antidote to this falsification of history, is the book Katharine the Great by Deborah Davis. Two aspects Katharine The Great: Katharine Graham of it must be considered. First, what Davis wrote about the And Her Washington Post Empire Post and its relationship to U.S. intelligence community. And by Deborah Davis second, what happened when Davis tried to first publish the New York: Sheridan Square Press, 1991 (third edition) book in 1979. 322 pages paperbound, $14.95 In her preface to the third edition, Davis writes: “This is the third It would be hard to exceed the hypocrisy of the days following edition of a book origi- the official announcement of the death of Katharine Graham nally written shortly on July 17. Even in death, Graham still had the power to after President Nixon re- make those, otherwise considered powerful in their own right, signed as a result of the grovel at her feet. Washington Post’s in- Eulogy after eulogy cited Graham’s alleged courage, and vestigation of the Water- even gutsiness, with respect to two publishing events: the gate scandal. The con- Pentagon Papers, and Watergate. In both cases, the truth is ceptual center of the directly contrary to the legend. In both cases, the Post was book is the question: spoon-fed material from a section of the U.S. intelligence Could Katharine Gra- community, designed to discredit President John F. -

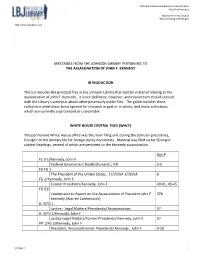

Materials from the Johnson Library Pertaining to the Assassination of John F

National Archives and Records Administration http://archives.gov National Archives Catalog https://catalog.archives.gov http://www.lbjlibrary.org MATERIALS FROM THE JOHNSON LIBRARY PERTAINING TO THE ASSASSINATION OF JOHN F. KENNEDY INTRODUCTION This list includes the principal files in the Johnson Library that contain material relating to the assassination of John F. Kennedy. It is not definitive, however, and researchers should consult with the Library's archivists about other potentially useful files. The guide includes those collections which have been opened for research in part or in whole, and those collections which are currently unprocessed or unavailable. WHITE HOUSE CENTRAL FILES (WHCF) This permanent White House office was the main filing unit during the Johnson presidency, though not the primary file for foreign policy documents. Material was filed under 60 major subject headings, several of which are pertinent to the Kennedy assassination. Box # FE 3-1/Kennedy, John F. Federal Government Deaths/Funerals, JFK 3-5 EX FG 1 The President of the United States, 11/22/64-1/10/64 9 FG 2/Kennedy, John F. Former Presidents/Kennedy, John F. 40-41, 43-45 FG 635 Commission to Report on the Assassination of President John F. 376 Kennedy (Warren Commission) JL 3/FG 1 Justice - Legal Matters/Presidential Assassinations 37 JL 3/FG 2/Kennedy, John F. Justice Legal Matters/Former Presidents/ Kennedy, John F. 37 PP 1/FG 2/Kennedy, John F. President, Personal/Former Presidents/ Kennedy, John F. 9-10 02/28/17 1 National Archives and Records Administration http://archives.gov National Archives Catalog https://catalog.archives.gov http://www.lbjlibrary.org (Cross references and letters from the general public regarding the assassination.) PR 4-1 Public Relations - Support after the Death of John F. -

Book Review: Laurel Leff. Buried by the Times: the Holocaust and America's Most Important Newspaper

Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal Volume 1 Issue 3 Article 11 December 2006 Book Review: Laurel Leff. Buried by the Times: The Holocaust and America's Most Important Newspaper Janine Minkler Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/gsp Recommended Citation Minkler, Janine (2006) "Book Review: Laurel Leff. Buried by the Times: The Holocaust and America's Most Important Newspaper," Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal: Vol. 1: Iss. 3: Article 11. Available at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/gsp/vol1/iss3/11 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Access Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Book Review Laurel Leff. Buried by the Times: The Holocaust and America’s Most Important Newspaper. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005. Pp. 426, cloth. $29.00 US. Reviewed by Janine Minkler, Department of Sociology and Social Work, Northern Arizona University Why did the New York Times persistently bury news of the Holocaust? asks Laurel Leff in her dramatic historical account of ‘‘America’s most important newspaper.’’ Leff, associate professor at Northeastern University and former journalist for the Wall Street Journal and Miami Herald, examines the complex combination of forces that led the Times to relegate news of the Holocaust to secondary status. She also sustains an uncompromising critique of this period in New York Times history. ‘‘No American newspaper was better positioned to highlight the Holocaust than the Times, and no American newspaper so influenced public discourse by its failure to do so. -

2020 Annual Report

2020 ANNUAL REPORT GRAHAM HOLDINGS 1300 NORTH 17TH STREET SUITE 1700 ARLINGTON, VA 22209 703 345 6300 GHCO.COM Revenue by Principal Operations EDUCATION 45% BROADCASTING 18% MANUFACTURING 14% HEALTHCARE 7% OTHER BUSINESSES 16% “2020 was a pivotal year at Graham Holdings Company. Against the backdrop of a global health crisis, we delivered stronger results than I would have forecast when COVID took hold in the spring…” Financial Highlights (IN THOUSANDS, EXCEPT PER SHARE AMOUNTS) 2020 2019 CHANGE Operating revenues $2,889,121 $2,932,099 (1%) Income from operations $ 100,407 $ 144, 546 (31%) Net income attributable to common shares $ 300,365 $ 327,855 (8%) Diluted earnings per common share $ 58.13 $ 61.21 (5%) Dividends per common share $ 5.80 $ 5.56 4% Common stockholders’ equity per share $ 754.45 $ 624.83 21% Diluted average number of common shares outstanding 5,139 5,327 (4%) OPERATING REVENUES INCOME FROM OPERATIONS ($ in millions) ($ in millions) 2020 2,889 2020 100 2019 2,932 2019 145 2018 2,696 2018 246 2017 2,592 2017 136 2016 2,482 2016 223 NET INCOME ATTRIBUTABLE TO COMMON SHARES RETURN ON AVERAGE COMMON ($ in millions) STOCKHOLDERS’ EQUITY 2020 300 2020 8.5% 2019 328 2019 10.5% 2018 271 2018 9.3% 2017 302 2017 11.3% 2016 169 2016 6.8% DILUTED EARNINGS PER COMMON SHARE ($) 2020 58.13 2019 61.2 1 2018 50.20 2017 53.89 2016 29.80 To Our Shareholders 2020 was a pivotal year at Graham Holdings for someone to get an item framed without Company. -

George Stevens, Jr., Lecturer the Seventh Annual Herblock Lecture April 15, 2010, the Library of Congress

George Stevens, Jr., Lecturer The Seventh Annual Herblock Lecture April 15, 2010, The Library of Congress The Herblock we know and honor really emerged when a young Herbert L. Block left his job at the Daily News in his native Chicago for Cleveland to be a cartoonist for the Newspaper Enterprise Service – a syndication company with the odd acronym NEA. He drew about the Depression and the New Deal and the rise of Fascist dictators in Europe – and he didn’t hesitate to let his readers know that he saw isolationism as a threat to Main Street America. After a time he couldn’t help but notice that NEA, which was owned by Scripps Howard, was getting “jittery” about his cartoons. His work expressed sharper opinions than his employers were accustomed to. And NEA was concerned that if a client cancelled Herblock, they might cancel the entire service. So when he was summoned to New York by Fred Ferguson, the NEA President – who was known around the office as Little Napoleon – and who started meetings by saying, “Well, have you seen what Roosevelt has done now?” It was pretty clear that Herb was about to be fired. He remembered sitting for a long time in the outer office cooling his heels, until Ferguson finally summoned him inside with what Herb remembered as an anguished smile – “an expression of mixed feelings never showed so clearly on a man’s face,” as Herb put it. It turned out that Ferguson had just been notified that Herblock had been awarded the Pulitzer Prize. -

The Media: 'Black Widow' Exposé Case Comes to Court

Click here for Full Issue of EIR Volume 13, Number 36, September 12, 1986 biotechnology. For his part, Rifkin has gloated in private The Media conversation that he and Robertson "think alike on econom ics." In 1979, Rifkin published The Emerging Order: God in the Age of Scarcity, in which he described the role of funda mentalism in replacing Western civilization with a "steady state society," an "age of conservation." Much of Rifkin's subsequent writings, including his better-known Entropy, elaborate the themes first developed there. Rifkin's major premise was that God created a "fixed universe," and that "anything [science and technology in 'Black Widow' expose particular] that undermines the 'fixed' purpose and order that God has given to the natural world is also sinful and an act of rebellion. ." case comes to court A zero-growth God A Washington Post legal spokesman has told EIR that Post Rifkin further argued that the notorious 19th-century sci owner Katharine Graham should decide during the week of entific fraud, the Second Law of Thermodynamics, consti Sept. 8-12, whether to contest the release of official records tuted God's "supreme law" of the universe. This "Entropy concerning the death of her husband. Law," wrote Rifkin, "tells us that every time available energy Richmond, Virginia, Circuit Court Judge Willard I. is used up, it creates disorder somewhere else in the surround Walker has scheduled a hearingfor Sept. 22. He will rule on ing environment. The massive flow-through of energy in a petition to release the death certificate and medical exam modem industrial society is creating massive disorder in the iner's reports, kept confidential since Philip L. -

Katharine Graham Et Le Washington Post1

Volume 10 Numéro 1 Février 2012 Katharine Graham et le Washington Post1 Cas produit par Jacqueline CARDINAL2 et le professeur Laurent LAPIERRE3 Katie Graham’s gonna get her tit caught in a big fat wringer if that’s published!4 – John Mitchell, procureur général des États-Unis, le 29 septembre 1972 Le 15 septembre 1972, cinq individus étaient accusés d’avoir cambriolé le quartier général du Parti démocrate situé dans le complexe Watergate, à Washington, afin de mettre la main sur des documents confidentiels et d’y installer du matériel d’écoute. Le même jour, deux anciens employés de la Maison-Blanche étaient mis en accusation pour complot dans cette affaire. Quelques instants plus tard, dans son Bureau ovale de la Maison-Blanche, le président des États- Unis Richard Nixon menaçait le Washington Post de représailles et traitait son avocat d’« enfant de chienne (son of a bitch) », à qui il « règlerait son compte ». Le cambriolage a déclenché ce qu’on a appelé « l’affaire Watergate », qui sera révélée au grand jour par deux journalistes du Washington Post, Carl Bernstein et Robert Woodward5. À la suite d’une délicate enquête en profondeur prouvant l’existence d’une caisse noire et les tentatives de camouflage menées par l’administration Nixon, ils signèrent des articles dévastateurs qui n’auraient pu être publiés sans le plein assentiment de l’éditrice et propriétaire du journal, Katharine Graham. Deux ans plus tard, soit le 8 août 1974, face à la menace imparable d’une mise en accusation (impeachment) devant le Congrès américain, Richard Nixon annonçait à la télévision qu’il démissionnait de son poste de président des États-Unis. -

`He Loved Me, and I Loved Him'

`He Loved Me, And I Loved Him' The G taad Sad Story of Phil Graham / By Katharine Graham carried on in his usual irreverent, breezy way. The second week in arly in 1940, I was invited by a February, he called me at work late friend to Sunday lunch with a one afternoon suggesting that we E group at the Ritz Carlton. have dinner at Harvey's, a famous old After we had lunched as long as we seafood restaurant next door to the could, someone suggested driving to Mayflower, where we could buy.the the country, and we spent the early edition of The Post. I had begun writing so-called light editorials and laying out parts of the editorial page. PERSONAL. HISTORY He would help me proofread. The evening was fine and fun. Phil afternoon there. At the end of the day, drove me home, and we talked for a everyone except Phil Graham and me long time. He told me that he loved had engagements, so he asked if I me and said we would be married and wanted to have dinner. We went to a go to Florida, if I could live with only restaurant, had a long dinner, talked two dresses, because I had to and laughed a lot, and drank until understand that he would never take quite late. I found him captivating. He anything from my father and we was a clerk for Supreme Court Justice would live on what he made. Stanley Reed while waiting to clerk My breath was taken away.