Urban Design

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Representations of Pleasure and Worship in Sankei Mandara Talia J

Mapping Sacred Spaces: Representations of Pleasure and Worship in Sankei mandara Talia J. Andrei Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Columbia University 2016 © 2016 Talia J.Andrei All rights reserved Abstract Mapping Sacred Spaces: Representations of Pleasure and Worship in Sankei Mandara Talia J. Andrei This dissertation examines the historical and artistic circumstances behind the emergence in late medieval Japan of a short-lived genre of painting referred to as sankei mandara (pilgrimage mandalas). The paintings are large-scale topographical depictions of sacred sites and served as promotional material for temples and shrines in need of financial support to encourage pilgrimage, offering travelers worldly and spiritual benefits while inspiring them to donate liberally. Itinerant monks and nuns used the mandara in recitation performances (etoki) to lead audiences on virtual pilgrimages, decoding the pictorial clues and touting the benefits of the site shown. Addressing themselves to the newly risen commoner class following the collapse of the aristocratic order, sankei mandara depict commoners in the role of patron and pilgrim, the first instance of them being portrayed this way, alongside warriors and aristocrats as they make their way to the sites, enjoying the local delights, and worship on the sacred grounds. Together with the novel subject material, a new artistic language was created— schematic, colorful and bold. We begin by locating sankei mandara’s artistic roots and influences and then proceed to investigate the individual mandara devoted to three sacred sites: Mt. Fuji, Kiyomizudera and Ise Shrine (a sacred mountain, temple and shrine, respectively). -

Bunkyo Walking Guidebook Basic Knowledge Which You Should Know

Bunkyo Walking Guidebook Basic knowledge which you should know Supervised by: Japan Walking Association Bunkyo District Health and Wellness Department Health Promotion Section Walking is an exercise In the beginning that is done among One sport that you can do without any tools or a gym is walking. Even for those who feel “sports” is a high hurdle to a wide range of ages. get over, a day doesn’t go by that we don’t walk. Walking isn’t just a way to transport from one place to another, walking is a fine sport once you understand the basics of it. Five Benefit □ Can do everyday For those who are thinking “I want to start doing sports, but I □ Anyone can do it don’t have time” “I want to do sports at my own pace” “I □ Hardly costs any money might be able to do sports if it wasn’t so time consuming”, □ Can balance your mind and health how about walking? Regardless of age, gender, or lifestyle □ Can lead to a fun lifestyle you can start walking. In addition, you can discover great Five Effects things about your city through a commute by walking. □ De-stress □ Vitalize your brain This guidebook is a summary of the basics of walking. If you □ Maintain and improve cardiopulmonary function read this, we are convinced that you will understand the □ Strengthen muscles health benefits and effective ways of walking. Walking is a □ Prevent and improve sport that by continuing you will understand the benefits. We lifestyle-related diseases have separately prepared a walking map. -

In Tokyo 2020 Celebrate New Year’S Day in Tokyo & Hawaii 12/26/19-1/1/20

in Tokyo 2020 Celebrate New Year’s Day in Tokyo & Hawaii 12/26/19-1/1/20 5nts/7days from: $2995 double/triple and $3595 single Traveling to Japan during New Year’s is a great opportunity to capture a rare glimpse into the modernization of traditional Japanese culture. It is a time when most Japanese people return home to partake in traditional ceremonies and festivities. On this very special Omiyage Weekender Tour, experience and be part of that tradition. If shopping is on your list, we have it covered, with visits to Tsukiji Market, Ameyoko, Komachi dori in Kamakura and free time in Odaiba. There is also a free afternoon and evening in Ikebukuro where all the favorites are located- Don Quijote, Daiso 100-yen Store, UNIQLO and sister store GU, Tokyu Hands, the Sunshine City Mall and Seibu Department Store. We have also included a visit to Ueno Zoo to see the pandas and on New Year’s Day time at Tokyo largest Daiso. We guarantee your first words will be, “Oh my gosh, this store is HUGE!” For sightseeing enjoy an overnight stay in Kamakura after seeing the Great Buddha so that we can visit the award-winning winter illumination, The Enoshima Sea Candle Illumination. There is also a visit to the Edo Period, Odawara Castle, Itchiku Kubota Art Musuem and views of Mt. Fuji from Oshino Hakkai. New Year’s Eve day includes a visit to Meiji Jinju Shrine and Shibuya Crossing Street just hours before the crowds arrive for the evening’s welcoming of the new year. -

100%トーキョー』 上演:2013年11月29日~12月1日 会場:東京芸術劇場 プレイハウス

フェスティバル/トーキョー13 『100%トーキョー』 上演:2013年11月29日~12月1日 会場:東京芸術劇場 プレイハウス Festival/Tokyo 2013 “100% Tokyo” November 29th to December 1st, 2013 Tokyo Metropolitan Theatre, Playhouse 親愛なる東京へ Dear Tokyo, この演劇プロジェクト(?)は統計学的な表象と演劇的な表現のコントラスト This theater project (?) plays with the contrast of statistic representation で遊ぶという試みです。こういった公演は典型的な世論調査同様の制限が and theatrical representation. Performances like this happen within the same limitations like representative public surveys do – they are only based 伴います――というのは、基本的に参加に同意してくださる人々の回答を土 on the answers of people who generally agree to participate. Our team 台にするものだからです。我々のチームはこの町の多様性を反映させるべく、 has undertaken great efforts to provide you with a diversity of participants 多様な方々に参加していただくよう、多大な努力を重ねてきました。従って演 that reflects your diversity. That also meant to avoid or even refuse theater 劇を熱烈に愛している演劇人の参加はご遠慮いただくこともありました。だ enthusiasts. からこそ、あなた方都民を代表している100名の「大使」たちの勇気と寛大さ This is why we especially thank the 100 “ambassadors” of your に感謝したいと思います。彼らの生活そのものが、この公演のためのリハー population for their courage and openness. They have rehearsed for this サルだったのです。ただ自分の経験を重ねるだけで、自分たちの「台詞」を覚 evening by just living their lives. They learned their “lines” by making their えてきました。こういった公演には稽古はありません――ですが、参加者全員 own experiences. A performance like this has not been rehearsed - but just organized so that everyone knows the rules and mechanisms of its various が様々な「ゲーム」のルールや仕組みを知るための構成はあります。舞台に上 “games”. Every evening they decide once again which line they say tonight. がるたびに、そのつど彼らは自分が言う台詞を決めていきます。上演台本はむ The script for this evening is rather a protocol and has been developed in しろ「実施要綱(プロトコル)」であり、参加者とともに作られたものです。こ collaboration with its participants. And it keeps developing throughout the れも公演を重ねていく毎に発展していきます。与えられた選択肢に同意する series of performances. Every evening its 100 protagonists decide afresh か否か、どのグループを選ぶか、100名の主役が舞台上で決めていくのです。 regarding each statement if they will join those who agree or those who disagree. -

Copyrighted Material

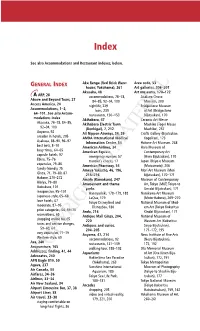

18_543229 bindex.qxd 5/18/04 10:06 AM Page 295 Index See also Accommodations and Restaurant indexes, below. GENERAL INDEX Aka Renga (Red Brick Ware- Area code, 53 house; Yokohama), 261 Art galleries, 206–207 Akasaka, 48 Art museums, 170–172 A ARP, 28 accommodations, 76–78, Asakura Choso Above and Beyond Tours, 27 84–85, 92–94, 100 Museum, 200 Access America, 24 nightlife, 229 Bridgestone Museum Accommodations, 1–2, bars, 239 of Art (Bridgestone 64–101. See also Accom- restaurants, 150–153 Bijutsukan), 170 modations Index Akihabara, 47 Ceramic Art Messe Akasaka, 76–78, 84–85, Akihabara Electric Town Mashiko (Togei Messe 92–94, 100 (Denkigai), 7, 212 Mashiko), 257 Aoyama, 92 All Nippon Airways, 34, 39 Crafts Gallery (Bijutsukan arcades in hotels, 205 AMDA International Medical Kogeikan), 173 Asakusa, 88–90, 96–97 Information Center, 54 Hakone Art Museum, 268 best bets, 8–10 American Airlines, 34 Hara Museum of busy times, 64–65 American Express Contemporary Art capsule hotels, 97 emergency number, 57 (Hara Bijutsukan), 170 Ebisu, 75–76 traveler’s checks, 17 Japan Ukiyo-e Museum expensive, 79–86 American Pharmacy, 54 (Matsumoto), 206 family-friendly, 75 Ameya Yokocho, 46, 196, Mori Art Museum (Mori Ginza, 71, 79–80, 87 215–216 Bijutsukan), 170–171 Hakone, 270–272 Amida (Kamakura), 247 Museum of Contemporary Hibiya, 79–80 Amusement and theme Art, Tokyo (MOT; Tokyo-to Ikebukuro, 101 parks Gendai Bijutsukan), 171 inexpensive, 95–101 Hanayashiki, 178–179, 188 Narukawa Art Museum Japanese-style, 65–68 LaQua, 179 (Moto-Hakone), 269–270 love hotels, -

Day 1, Sunday March 04, 2018 Day 2, Monday March 05, 2018

6 Day VIP Tokyo Food Trip Day 1, Sunday March 04, 2018 1: Rest Up at the Andaz Tokyo (Lodging) Address: Japan, 〒105-0001 Tōkyō-to, Minato City, Toranomon, 1-chōme−23−4 虎ノ門ヒルズ About: The Andaz Tokyo is a boutique-like property from the Hyatt brand in the business district of Toranomon. Despite its big-name associations, the hotel incorporates local design elements like washi paper artwork and the massive bonsai tree in the lobby. The property features three restaurants: a grill specialize in Japanese aged beef, a burger restaurant, and a small sushi bar. The highlight here? The rooftop bar, which has more to it than just the views. The skilled bartenders preside over a menu of signature cocktails, and can whip up an excellent iteration of whatever you're craving. Opening hours Sunday: Open 24 hours Monday: Open 24 hours Tuesday: Open 24 hours Wednesday: Open 24 hours Thursday: Open 24 hours Friday: Open 24 hours Saturday: Open 24 hours Phone number: +81 3-6830-1234 Website: https://www.hyatt.com/en-US/hotel/japan/andaz-tokyo-toranomon- hills/tyoaz?src=corp_lclb_gmb_seo_aspac_tyoaz Reviews https://www.yelp.com/biz/%E3%82%A2%E3%83%B3%E3%83%80%E3%83%BC%E3%82%BA- %E6%9D%B1%E4%BA%AC-%E8%99%8E%E3%83%8E%E9%96%80%E3%83%92%E3%83%AB%E3%82%BA- %E6%B8%AF%E5%8C%BA https://www.tripadvisor.com/Hotel_Review-g14129647-d6485175-Reviews-Andaz_Tokyo_Toranomon_Hills- Toranomon_Minato_Tokyo_Tokyo_Prefecture_Kanto.html Day 2, Monday March 05, 2018 1: CLOSED - No Nonsense Coffee and Yummy Treats at Toranomon Koffee (Cafe) Address: Japan, 〒105-0001 Tōkyō-to, Minato-ku, 港区Toranomon, 1 Chome−1−23−3 About: With single source espresso and a rich house blend, Toranomon Koffee is a must for serious coffee lovers. -

Tokyo to Osaka: Subduction by Slow Train*

TOKYO TO OSAKA: SUBDUCTION BY SLOW TRAIN* Wes Gibbons 2020 This Holiday Geology guide offers an alternative approach to train travel between Tokyo and the Osaka/Kyoto/Nara area. The journey takes it slow by using the extensive network of local trains, giving time to enjoy the scenery and sample a taste of everyday life in Japan. Instead of hurtling from Tokyo to Osaka by Shinkansen bullet train in three hours, our route takes over a week as we meander from the suburbs of Greater Tokyo to the peaceful shrines of Kamakura and the spa-town of Atami, skirting Mount Fuji to pass Nagoya on the way to the isolated splendours of the Kii Peninsula before reconnecting with the urban masses on the approach to Osaka. For those with extra time to spend, we recommend finishing the trip off with a visit to Nara (from where Kyoto is less than an hour away). The journey is a very Japanese experience. You will see few non-Japanese people in most of the places visited, and it is difficult not to be impressed with the architecture, history, scenery and tranquillity of the many shrines passed on the way. The Kii Peninsula in particular offers a glimpse into Old Japan, especially because the route includes walking along parts of the Kumano Kudo ancient pilgrimage trail (Days 5-7). *Cite as: Gibbons, W. 2020. Holiday Geology Guide Tokyo to Osaka. http://barcelonatimetraveller.com/wp- content/uploads/2020/03/TOKYO-TO-OSAKA.pdf BARCELONA TIME TRAVELLER COMPANION GUIDE Background. The route described here offers a slow and relatively cheap rail journey from Tokyo to Osaka. -

Ferris Hills News May 2017

MAY 2017 Ferris Hills at West Lake LakeHEAD Tokyo in Full Bloom Japan may be famous for its cherry blossoms, but springtime in Tokyo brings an abundance of other flowers and flower festivals. By the end of April, many of Japan’s cherry blossoms have already flowered, Celebrating May but Tokyo’s city dwellers still have plenty of blooming flowers to look forward to. The Nezu Shrine is a quiet place for 11 months out of the year, but by the first week Clean Car Month in May, its 3,000 azalea plants burst into a palette of bright colors. The Bunkyo Azalea Festival, or Tsutsuji Matsuri, Inventors Month attracts thousands of visitors during Golden Week, its busiest viewing week. The 300-year-old azalea garden Vinegar Month is home to rare varieties, such as the black karafune flower, and is complete with a Shinto shrine, bridges running over streams, traditional Toriii gates, and women dressed in their best kimonos. Teacher Day Across town is yet another sacred spot draped in May 2 wondrous springtime color: the Kameido Tenjin Shrine. This shrine is home to its famous trellises boasting a sea of cascading purple wisteria vines. The wisteria Astronaut Day May 5 were planted 300 years ago when the original temple was built. Visitors can stroll over the shrine’s beautiful red bridge, spying darting koi and lounging turtles in Kentucky Derby Day the pond. The wisteria are so alluring that old Japanese May 6 shoguns made pilgrimages to visit the garden. Many of Japan’s most celebrated artists have captured the International Nurses Day garden’s scenic serenity in color prints. -

Calendar Events to Be Enjoyed in May 2013

1. Published by Tourist Information Center of Japan National Tourism Organization and all rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part without written permission is prohibited. ©2013 Japan National Tourism Organization. 2. Dates and functions are subject to change without notice. Be sure to check the latest information in advance. 3. Events marked with ◎ are the major events. 4. Dates of events marked with ◇ are the same every year. 5. Japanese explanations appearing at the bottom of each entry give the name of the event and the nearest railway station in Japanese. Point to this Japanese when you need help from a Japanese passerby. 6. Please refer to URL (basically in Japanese) for each event. 7. The subway Lines and Station Numbers are indicated in parentheses ( ). Note: The Internet Website of Japan National Tourism Organization is available at <http://www.jnto.go.jp>. Calendar Events to be enjoyed in May 2013 TOKYO 東京 Date Apr. 6 ~ May 6 Bunkyo Tsutsuji Matsuri, Azalea Festival at Nezu Shrine, Bunkyo-ku. One can enjoy a view of azelea blossoms in the precincts of the Shrine. Performing arts such as Gongen-Taiko (Japanese drumming performance) and Urayasu-no-mai (Shinto dance with music) are held in the precincts of the Shrine from 12 noon on May 3rd, 4th and 5th. Admission to the Azalea Garden is \200. http://www.nedujinja.or.jp/tutuji/t.html Access The Chiyoda Subway Line to Nezu Sta. (C 14) 所在地 文京区 根津神社 文京つつじまつり 最寄駅 千代田線根津駅 Date Apr. 20 ~ May 6 Fuji Matsuri, Wisteria Festival of Kameido Tenjin (or Tenmangu) Shrine, Koto-ku. -

Hiroshi Akatsuka Was Born in Kyoto, Japan in 1962

4th International Workshop on Plasma Scientech for All Something(Plasas-4) October 8-10, 2011, Beijing, China Summer Palace The Forbidden City Invitation to the workshop We organize a research workshop with a purpose to well bridge internationally-acting scientists and engineers. The workshop consists of a limited number of selected people in China and Japan. The workshop will be carried out through - exchanging academic information on plasma science and technology and their applications, - promoting plasma science and technology, - collaborating in research projects. The workshop will provide the scientific and technological fruit obtained by attendees so far. By discussing their scientific and technological viewpoints, the attendees will possess the information as common property. The presentation will be done for 20 min-oral presentation and 10 min discussion. Organizing Committees Yuan Fangli (Chair) (Institute of Process Engineering, Chinese Academy of Sciences) Akatsuka Hiroshi (Co-Chair) Tokyo Institute of Technology, Japan Advisory Committees Yukimura Ken National Institute of Advanced Industrial Sciences and Technology, Japan Chen Qiang Beijing Institute of Graphic Communication, China Workshop venue: Institute of Process Engineering, Zhongguancun, Haidian, Beijing, China Institute of Process Engineering, CAS The workshop venue is located Zhongguancun of Beijing, China Invited Speakers Wang Haixing Beihang University Yukimura Ken National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology, Japan Hu Peng Institute of Process Engineering of Chinese Academy of Sciences Takaki Koichi Iwate University Liu Dawei Huazhong University of Science and Technology Yamada Hideaki National Institute of Industrial Science and Technology, Japan Feng Wenran Beijing Institute of Petrochemical Technology, China Ohtsu Yasunori Saga University, Japan Zhang Yuefei Beijing University of Technology, Beijing, P. -

Shinto Shrines: a Guide to the Sacred Sites of Japans Ancient Religion Pdf, Epub, Ebook

SHINTO SHRINES: A GUIDE TO THE SACRED SITES OF JAPANS ANCIENT RELIGION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Joseph Cali,John Dougill | 232 pages | 30 Nov 2012 | University of Hawai'i Press | 9780824837136 | English | Honolulu, HI, United States Shinto Shrines: A Guide to the Sacred Sites of Japans Ancient Religion PDF Book The side panels are carved in deep relief and the gate connects to the same type of sukashi-be i fence which we saw on the Ueno Toshogu shrine. It is of a type one finds at Buddhist temples. Project MUSE Mission Project MUSE promotes the creation and dissemination of essential humanities and social science resources through collaboration with libraries, publishers, and scholars worldwide. This item doesn't belong on this page. Add to Wishlist. Notice the intricate carving and polychrome under the eaves. KYOTO pp. So what exactly is Shinto and what are its beliefs and rituals. Indeed, this one was modeled after the yumedono of Nara's famous Horyuji. This is followed by a fully illustrated guide to 57 major Shinto shrines throughout Japan, many of which have been designated World Heritage Sites or National Treasures. These are surrounded by plum, pine, and bamboo trees sho, chiku, bai , the Confucian "Three friends of Winter," a symbol of good fortune and prosperity. Apparently, the body was originally interred in a sitting position inside the stupa-shaped crypt. Shinto believes in the kami, a divine power that can be found in all things. Photo by Travis Wise via Flickr Shinto is deeply rooted in the Japanese people and their cultural activities. -

2017 Japan Travel Itinerary (Korea/Japan Summer Program)

ARCH 499.111 Japanese Studies in Architecture (3 Credits) 2017 Japan Travel Itinerary (Korea/Japan Summer Program) June 13 to June 26, 2017 Image from https://www.ox.ac.uk/about/international-oxford/oxfords-global-links/asia-east/japan?wssl=1 “Japan is the global imagination’s default setting for the future.” - William Gibson, Observer 2001 “Japanese do many things in a way that runs directly counter to European ideas of what is natural and proper.” - Basil Hall Chamberlain, Things Japanese “When the past is with you , it may as well be present; and if it is present, it will be future as well.” - William Gibson, Neuromancer Instructor: Katsu Muramoto 325 Stuckeman Family Building Contact: Email - [email protected]; Tel 814-863-0793 ABOUT THIS BOOKLET Most of the information listed was compiled from various sources including, web sites, magazines and books in order to assist you during your trip to Japan. The abbreviations of the quoted from in this booklet are Archdaily (AD), wikiar- chitecture (WA), Phaidon Atlas, Architecture for Architects (PA),Wikipedia (W), Lonely Planet (LP), Go to Japan (GTJ), Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), Japan Guide.com (JG), Kansai Window (KW), Kyoto Convention Bureau (KCB), Tokyo Convention & Visitors Bureau (TCVB) and Fodor’s Japan (FJ). The booklet starts with a general introduction to Japan, followed by a detailed schedule of activities. Most of the infor- mation is, I believe, accurate and reliable, however, some we may find be out of date. There are many new buildings not listed as part of our daily detailed schedule of activities on which I am still gathering information.