A Study of the Salem Commonage Land Claim

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boer War Association Queensland

Boer War Association Queensland Queensland Patron: Major General Professor John Pearn, AO RFD (Retd) Monumentally Speaking - Queensland Edition Committee Newsletter - Volume 12, No. 1 - March 2019 As part of the service, Corinda State High School student, Queensland Chairman’s Report Isabel Dow, was presented with the Onverwacht Essay Medal- lion, by MAJGEN Professor John Pearn AO, RFD. The Welcome to our first Queensland Newsletter of 2019, and the messages between Ermelo High School (Hoërskool Ermelo an fifth of the current committee. Afrikaans Medium School), South Africa and Corinda State High School, were read by Sophie Verprek from Corinda State Although a little late, the com- High School. mittee extend their „Compli- ments of the Season‟ to all. MAJGEN Professor John Pearn AO, RFD, together with Pierre The committee also welcomes van Blommestein (Secretary of BWAQ), laid BWAQ wreaths. all new members and a hearty Mrs Laurie Forsyth, BWAQ‟s first „Honorary Life Member‟, was „thank you‟ to all members who honoured as the first to lay a wreath assisted by LTCOL Miles have stuck by us; your loyalty Farmer OAM (Retd). Patron: MAJGEN John Pearn AO RFD (Retd) is most appreciated. It is this Secretary: Pierre van Blommestein Chairman: Gordon Bold. Last year, 2018, the Sherwood/Indooroopilly RSL Sub-Branch membership that enables „Boer decided it would be beneficial for all concerned for the Com- War Association Queensland‟ (BWAQ) to continue with its memoration Service for the Battle of Onverwacht Hills to be objectives. relocated from its traditional location in St Matthews Cemetery BWAQ are dedicated to evolve from the building of the mem- Sherwood, to the „Croll Memorial Precinct‟, located at 2 Clew- orial, to an association committed to maintaining the memory ley Street, Corinda; adjacent to the Sherwood/Indooroopilly and history of the Boer War; focus being descendants and RSL Sub-Branch. -

A Classification of the Subtropical Transitional Thicket in the Eastern Cape, Based on Syntaxonomic and Structural Attributes

S. Afr. J. Bot., 1987, 53(5): 329 - 340 329 A classification of the subtropical transitional thicket in the eastern Cape, based on syntaxonomic and structural attributes D.A. Everard Department of Plant Sciences, Rhodes University, Grahamstown, 6140 Republic of South Africa Accepted 11 June 1987 Subtropical transitional thicket, traditionally known as valley bushveld, covers a significant proportion of the eastern Cape. This paper attempts to classify the subtropical transitional thicket into syntaxonomic and structural units and relate it to other thicket types on a continental basis. Twelve sites along a rainfall gradient were sampled for floristic and structural attributes. The floristic data were classified using TWINSPAN. Results indicate that the class subtropical transitional thicket has at least two orders of vegetation, namely kaffrarian thicket and kaffrarian succulent thicket. Two forms of thicket were recognized for both these orders viz. mesic kaffrarian thicket and xeric kaffrarian thicket for the kaffrarian thicket and mesic succulent thicket and xeric succulent thicket for the kaffrarian succulent thicket. Ordination of site data by DECORANA grouped sites according to these vegetation categories and in a sequence along axis 1 to which the rainfall gradient can be clearly related. Variation within the mesic kaffrarian thicket was however greater than between some of the other thicket types, indicating that more data are required before these forms of thicket can be formalized. Composition, endemism, diversity and the environmental controls on the distribution of the thicket types are discussed. 'n Aansienlike gedeelte van die Oos-Kaap word beslaan deur subtropiese oorgangsruigte, wat tradisioneel as valleibosveld bekend is. Hierdie studie is 'n poging om subtropiese oorgangsruigte in sintaksonomiese en strukturele eenhede te klassifiseer en dit op 'n kontinentale basis in verband met ander ruigtetipes te bring. -

The Valuation of Changes to Estuary Services in South Africa As a Result of Changes to Freshwater Inflow

THE VALUATION OF CHANGES TO ESTUARY SERVICES IN SOUTH AFRICA AS A RESULT OF CHANGES TO FRESHWATER INFLOW BY SG HOSKING, TH WOOLDRIDGE, G D1MOPOULOS, M MLANGENI, C-H LIN, M SALE AND M DU PREEZ DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS AND ECONOMIC HISTORY AND DEPARTMENT OF ZOOLOGY/ UNIVERSITY OF PORT ELIZABETH REPORT TO THE WATER RESEARCH COMMISSION WRC REPORT NO: 1304/1/04 ISBN NO: 1-77005-278-X DECEMBER 2004 II DISCLAIMER This report emanates from a project financed by the Water Research Commission (WRC) and is approved for publication. Approval does not signify that the contents necessarily reflect the views and policies of the WRC or the members of the project steering committee, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation for use. Ill ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The research in this report emanated from a project funded by the Water Research Commission and entitled: "THE VALUATION OF CHANGES TO ESTUARY SERVICES IN SOUTH AFRICA AS A RESULT OF CHANGES TO FRESHWATER INFLOW" The authors contributed in the following sections: T Wooidridge - Chapters One and Five G Dimopoulos - Chapters One, Three, Five and Six C-H Lin - Chapters Four and Seven M Sale - Chapters Two, Five and Six S Hosking - all Chapters M du Preez assisted S Hosking with the editorial work M Mlangeni - Chapters Five and Six. The Steering Committee responsible for this project consisted of the following persons: Dr GR Backeberg Water Research Commission (Chairman) Dr SA Mitchell Water Research Commission Dr J Turpie University of Cape Town Mr A Leiman University of Cape Town Prof MF Viljoen University of the Free State Dr J Adams University of Port Elizabeth Dr M du Preez University of Port Elizabeth The funding of the project by the Water Research Commission and the contribution of the members of the Steering Committee is gratefully acknowledged. -

Wildlife-Wonder.Pdf

EASTERN CAPE GAME AND NATURE RESERVES TSITSIKAMMA GARDEN ROUTE NATIONAL PARK Along the South Coast of South Africa lies one of to mountain areas, and are renowned for its diverse the most beautiful stretches of coastline in the natural and cultural heritage resources. Managed world, home to the Garden Route National Park. A by South African National Parks, it hosts a variety mosaic of ecosystems, it encompasses the world of accommodation options, activities and places of renowned Tsitsikamma and Wilderness sections, interest. the Knysna Lake section, a variety of mountain catchments, Southern Cape indigenous forest and www.sanparks.co.za/parks/garden_route/ associated Fynbos areas. These areas resemble a +27 (0) 42 281 1607 [email protected] montage of landscapes and seascapes, from ocean KOUGA BAVIAANSKLOOF NATURE RESERVE LOMBARDINI GAME FARM BAVIAANSKLOOF With its World Heritage Site status, the Situated in the picturesque Seekoei River valley, Baviaanskloof Nature Reserve is home to the Lombardini Game Farm is an absolute gem! With biggest wilderness area in the country and is daily guided tours around the game park, you also one of the eight protected areas of the Cape are sure to see most of our beautiful animals. Floristic Region. The Baviaanskloof Mega-Reserve Luxurious en-suite in-house accommodation offers covers 200km of unspoiled, rugged mountainous peace and tranquillity to guests. The warmth of terrain with spectacular landscapes hosting more the thatch roof makes you feel right at home. Semi than a thousand different plant species, including self-catering poolrooms, with stunning interior, will the Erica and Protea families and species of ancient make you want to stay another day. -

The Third War of Dispossession and Resistance in the Cape of Good Hope Colony, 1799–1803

54 “THE WAR TOOK ITS ORIGINS IN A MISTAKE”: THE THIRD WAR OF DISPOSSESSION AND RESISTANCE IN THE CAPE OF GOOD HOPE COLONY, 1799–1803 Denver Webb, University of Fort Hare1 Abstract The early colonial wars on the Cape Colony’s eastern borderlands and western Xhosaland, such as the 1799–1803 war, have not received as much attention from military historians as the later wars. This is unexpected since this lengthy conflict was the first time the British army fought indigenous people in southern Africa. This article revisits the 1799–1803 war, examines the surprisingly fluid and convoluted alignments of participants on either side, and analyses how the British became embroiled in a conflict for which they were unprepared and for which they had little appetite. It explores the micro narrative of why the British shifted from military action against rebellious Boers to fighting the Khoikhoi and Xhosa. It argues that in 1799, the British stumbled into war through a miscalculation – a mistake which was to have far-reaching consequences on the Cape’s eastern frontier and in western Xhosaland for over a century. Introduction The eighteenth- and nineteenth-century colonial wars on the Cape Colony’s eastern borderlands and western Xhosaland (emaXhoseni) have received considerable attention from historians. For reasons mostly relating to the availability of source material, the later wars are better known than the earlier ones. Thus the War of Hintsa (1834–35), the War of the Axe (1846–47), the War of Mlanjeni (1850–53) and the War of Ngcayecibi (1877–78) have received far more coverage by contemporaries and subsequently by historians than the eighteenth-century conflicts.2 The first detailed examination of Scientia Militaria, South African the 1799–1803 conflict, commonly known as Journal of Military Studies, Vol the Third Frontier War or third Cape–Xhosa 42, Nr 2, 2014, pp. -

Proquest Dissertations

I^fefl National Library Bibliotheque naiionale • T • 0f Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Direction des acquisitions et Bibliographic Services Branch des services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa, Ontario Ottawa (Ontario) K1A0N4 K1A0N4 v'o,/rM<* Volt? rottiU'iKc Our lilu Nolle tit&rtsnca NOTICE AVIS The quality of this microform is La qualite de cette microforme heavily dependent upon the depend grandement de la qualite quality of the original thesis de la these soumise au submitted for microfilming. microfilmage. Nous avons tout Every effort has been made to fait pour assurer une qualite ensure the highest quality of superieure de reproduction. reproduction possible. If pages are missing, contact the S'il manque des pages, veuillez university which granted the communiquer avec I'universite degree. qui a confere Ie grade. Some pages may have indistinct La qualite d'impression de print especially if the original certaines pages peut laisser a pages were typed with a poor desirer, surtout si les pages typewriter ribbon or if the originates ont ete university sent us an inferior dactylographies a I'aide d'un photocopy. ruban use ou si I'univeioite nous a fait parvenir une photocopie de qualite inferieure. Reproduction in full or in part of La reproduction, meme partielle, this microform is governed by de cette microforme est soumise the Canadian Copyright Act, a la Loi canadienne sur Ie droit R.S.C. 1970, c. C-30, and d'auteur, SRC 1970, c. C-30, et subsequent amendments. ses amendements subsequents. Canada Maqoma: Xhosa Resistance to the Advance of Colonial Hegemony (1798-1873) by Timothy J. -

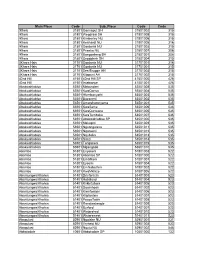

Mainplace Codelist.Xls

Main Place Code Sub_Place Code Code !Kheis 31801 Gannaput SH 31801002 315 !Kheis 31801 Wegdraai SH 31801008 315 !Kheis 31801 Kimberley NU 31801006 315 !Kheis 31801 Kenhardt NU 31801005 316 !Kheis 31801 Gordonia NU 31801003 315 !Kheis 31801 Prieska NU 31801007 306 !Kheis 31801 Boegoeberg SH 31801001 306 !Kheis 31801 Grootdrink SH 31801004 315 ||Khara Hais 31701 Gordonia NU 31701001 316 ||Khara Hais 31701 Gordonia NU 31701001 315 ||Khara Hais 31701 Ses-Brugge AH 31701003 315 ||Khara Hais 31701 Klippunt AH 31701002 315 42nd Hill 41501 42nd Hill SP 41501000 426 42nd Hill 41501 Intabazwe 41501001 426 Abakwahlabisa 53501 Mabundeni 53501008 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 KwaQonsa 53501004 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 Hlambanyathi 53501003 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 Bazaneni 53501002 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 Amatshamnyama 53501001 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 KwaSeme 53501006 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 KwaQunwane 53501005 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 KwaTembeka 53501007 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 Abakwahlabisa SP 53501000 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 Makopini 53501009 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 Ngxongwana 53501011 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 Nqotweni 53501012 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 Nqubeka 53501013 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 Sitezi 53501014 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 Tanganeni 53501015 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 Mgangado 53501010 535 Abambo 51801 Enyokeni 51801003 522 Abambo 51801 Abambo SP 51801000 522 Abambo 51801 Emafikeni 51801001 522 Abambo 51801 Eyosini 51801004 522 Abambo 51801 Emhlabathini 51801002 522 Abambo 51801 KwaMkhize 51801005 522 Abantungwa/Kholwa 51401 Driefontein 51401003 523 -

Conference Proceedings 2006

FOSAF THE FEDERATION OF SOUTHERN AFRICAN FLYFISHERS PROCEEDINGS OF THE 10 TH YELLOWFISH WORKING GROUP CONFERENCE STERKFONTEIN DAM, HARRISMITH 07 – 09 APRIL 2006 Edited by Peter Arderne PRINTING & DISTRIBUTION SPONSORED BY: sappi 1 CONTENTS Page List of participants 3 Press release 4 Chairman’s address -Bill Mincher 5 The effects of pollution on fish and people – Dr Steve Mitchell 7 DWAF Quality Status Report – Upper Vaal Management Area 2000 – 2005 - Riana 9 Munnik Water: The full picture of quality management & technology demand – Dries Louw 17 Fish kills in the Vaal: What went wrong? – Francois van Wyk 18 Water Pollution: The viewpoint of Eco-Care Trust – Mornē Viljoen 19 Why the fish kills in the Vaal? –Synthesis of the five preceding presentations 22 – Dr Steve Mitchell The Elands River Yellowfish Conservation Area – George McAllister 23 Status of the yellowfish populations in Limpopo Province – Paul Fouche 25 North West provincial report on the status of the yellowfish species – Daan Buijs & 34 Hermien Roux Status of yellowfish in KZN Province – Rob Karssing 40 Status of the yellowfish populations in the Western Cape – Dean Impson 44 Regional Report: Northern Cape (post meeting)– Ramogale Sekwele 50 Yellowfish conservation in the Free State Province – Pierre de Villiers 63 A bottom-up approach to freshwater conservation in the Orange Vaal River basin – 66 Pierre de Villiers Status of the yellowfish populations in Gauteng Province – Piet Muller 69 Yellowfish research: A reality to face – Dr Wynand Vlok 72 Assessing the distribution & flow requirements of endemic cyprinids in the Olifants- 86 Doring river system - Bruce Paxton Yellowfish genetics projects update – Dr Wynand Vlok on behalf of Prof. -

Statistical Based Regional Flood Frequency Estimation Study For

Statistical Based Regional Flood Frequency Estimation Study for South Africa Using Systematic, Historical and Palaeoflood Data Pilot Study – Catchment Management Area 15 by D van Bladeren, P K Zawada and D Mahlangu SRK Consulting & Council for Geoscience Report to the Water Research Commission on the project “Statistical Based Regional Flood Frequency Estimation Study for South Africa using Systematic, Historical and Palaeoflood Data” WRC Report No 1260/1/07 ISBN 078-1-77005-537-7 March 2007 DISCLAIMER This report has been reviewed by the Water Research Commission (WRC) and approved for publication. Approval does not signify that the contents necessarily reflect the views and policies of the WRC, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation for use EXECUTIVE SUMMARY INTRODUCTION During the past 10 years South Africa has experienced several devastating flood events that highlighted the need for more accurate and reasonable flood estimation. The most notable events were those of 1995/96 in KwaZulu-Natal and north eastern areas, the November 1996 floods in the Southern Cape Region, the floods of February to March 2000 in the Limpopo, Mpumalanga and Eastern Cape provinces and the recent floods in March 2003 in Montagu in the Western Cape. These events emphasized the need for a standard approach to estimate flood probabilities before developments are initiated or existing developments evaluated for flood hazards. The flood peak magnitudes and probabilities of occurrence or return period required for flood lines are often overlooked, ignored or dealt with in a casual way with devastating effects. The National Disaster and new Water Act and the rapid rate at which developments are being planned will require the near mass production of flood peak probabilities across the country that should be consistent, realistic and reliable. -

CONTINUITY and CHANGE in CISXEI CHIFZSHIP by J. B. Peires the Conventional Wisdom of South African Ethnologists, Whether Liberal

CONTINUITY AND CHANGE IN CISXEI CHIFZSHIP by J. B. Peires The conventional wisdom of South African ethnologists, whether liberal or conservative, has been dominated by the idea that African polities operated according to certain fixed rules (tlcustomsw)which were hallowed by tradition and therefore never chaaged. (1) A corolla-ry of this is that, if these rules could be correctly identified and fairly applied, everyone would be satisfied and chiefship could perhaps be saved. (2) It is, however, fairly well established that genealogies are often falsified, that new rules are coined and old rules bent to accommodate changing configurations of power, and that "age-old" customs may turn out to be fairly recent innovations; in short, that "organisational ideas do not directly control action, but only the interpretation of actionr1.(3) This conventional wisdom was successfully challenged by Comaroff in an important article, Itchiefship in a South African Homelandt1,which demonstrated that, by adhering too closely to the formal features of traditional government and politics among the Tswana, especially those concerning succession, the Government wrecked the political processes which had enabled the 'Pswam to choose the most suitable candidate as chief. (4) And yet Comarofffs article begs a good many questions. Let us imagine that the Government ethnologists read the article, and as a result allow Tswana chiefs to compete for office as before, permitting flconsultativedecision-making and participation in executive processes". (5) Would this prevent the Tswana chiefship from dying? Can we, in fact, discuss chiefship in political terms alone without considering whether the material conditions in which it flourished still exist? The present article will attempt to situate the question of chiefship in a somewhat wider framework than that usually provided by administrative theory or transactional analysis. -

Explore the Eastern Cape Province

Cultural Guiding - Explore The Eastern Cape Province Former President Nelson Mandela, who was born and raised in the Transkei, once said: "After having travelled to many distant places, I still find the Eastern Cape to be a region full of rich, unused potential." 2 – WildlifeCampus Cultural Guiding Course – Eastern Cape Module # 1 - Province Overview Component # 1 - Eastern Cape Province Overview Module # 2 - Cultural Overview Component # 1 - Eastern Cape Cultural Overview Module # 3 - Historical Overview Component # 1 - Eastern Cape Historical Overview Module # 4 - Wildlife and Nature Conservation Overview Component # 1 - Eastern Cape Wildlife and Nature Conservation Overview Module # 5 - Nelson Mandela Bay Metropole Component # 1 - Explore the Nelson Mandela Bay Metropole Module # 6 - Sarah Baartman District Municipality Component # 1 - Explore the Sarah Baartman District (Part 1) Component # 2 - Explore the Sarah Baartman District (Part 2) Component # 3 - Explore the Sarah Baartman District (Part 3) Component # 4 - Explore the Sarah Baartman District (Part 4) Module # 7 - Chris Hani District Municipality Component # 1 - Explore the Chris Hani District Module # 8 - Joe Gqabi District Municipality Component # 1 - Explore the Joe Gqabi District Module # 9 - Alfred Nzo District Municipality Component # 1 - Explore the Alfred Nzo District Module # 10 - OR Tambo District Municipality Component # 1 - Explore the OR Tambo District Eastern Cape Province Overview This course material is the copyrighted intellectual property of WildlifeCampus. -

Towards an Inculturated Understanding of the Eucharist

THE SACRIFICE OF THE MASS AND THE CONCEPT OF SACRIFICE AMONG THE XHOSA: TOWARDS AN INCULTURATED UNDERSTANDING OF THE EUCHARIST. By SITHEMBELE SIPUKA Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF THEOLOGY in the subject of SYSTEMATIC THEOLOGY atthe UNVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA PROMOTER: PROF MB G MOTLHABI NOVEMBER 2000 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank all those who in various ways have helped and supported me during the writing of this thesis. I thank the people of Qoqodala and Zigudu parish my interaction with whom inspired the topic of this thesis. I also thank the promoter of this thesis, Prof. Mokgethi Motlhabi, who helped me with its formulation and made sure that I do not stray from the topic. His clarity and thoroughness, while still being friendly, were greatly appreciated. In particular I would like to thank my bishop, Rt. Rev .. H N Lenhof, for making me believe that I could carry out a project of this nature and for supporting me both morally and financially while I was trying to make it happen. Fr. Bonaventure Hinwood, with his 'nagging', helped me to embark on this project before it was too late. My thanks also goes to the Franciscans and the Institute for Catholic Education who fed and accommodated me almost for nothing. Thanks to the SACBC's seminaries' department and to my colleagues who ungrudgingly released me to work full time on this thesis. Thanks to Fr. Enrico Parry, for helping me with the computer for the layout of this work and to the St.