Dvoretsky's Endgame Manual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Weltenfern a Commented Selection of Some of My Works Containing 149 Originals

Weltenfern A commented selection of some of my works containing 149 originals by Siegfried Hornecker Dedicated to the memory of Dan Meinking and Milan Velimirovi ć who both encouraged me to write a book! Weltenfern : German for other-worldly , literally distant from the world , describing a person’s attitude In the opinion of the author the perfect state of mind to compose chess problems. - 1 - Index 1 – Weltenfern 2 – Index 3 – Legal Information 4 – Preface 6 – 20 ideas and themes 6 – Chapter One: A first walk in the park 8 – Chapter Two: Schachstrategie 9 – Chapter Three: An anticipated study 11 – Chapter Four: Sleepless nights, or how pain was turned into beauty 13 – Chapter Five: Knightmares 15 – Chapter Six: Saavedra 17 – Chapter Seven: Volpert, Zatulovskaya and an incredible pawn endgame 21 – Chapter Eight: My home is my castle, but I can’t castle 27 – Intermezzo: Orthodox problems 31 – Chapter Nine: Cooperation 35 – Chapter Ten: Flourish, Knightingale 38 – Chapter Eleven: Endgames 42 – Chapter Twelve: MatPlus 53 – Chapter 13: Problem Paradise and NONA 56 – Chapter 14: Knight Rush 62 – Chapter 15: An idea of symmetry and an Indian mystery 67 – Information: Logic and purity of aim (economy of aim) 72 – Chapter 16: Make the piece go away 77 – Chapter 17: Failure of the attack and the romantic chess as we knew it 82 – Chapter 18: Positional draw (what is it, anyway?) 86 – Chapter 19: Battle for the promotion 91 – Chapter 20: Book Ends 93 – Dessert: Heterodox problems 97 – Appendix: The simple things in life 148 – Epilogue 149 – Thanks 150 – Author index 152 – Bibliography 154 – License - 2 - Legal Information Partial reprint only with permission. -

Top 10 Checkmate Pa Erns

GM Miguel Illescas and the Internet Chess Club present: Top 10 Checkmate Pa=erns GM Miguel Illescas doesn't need a presentation, but we're talking about one of the most influential chess players in the last decades, especially in Spain, just to put things in the right perspective. Miguel, so far, has won the Spanish national championship of 1995, 1998, 1999, 2001, 2004, 2005, 2007, and 2010. In team competitions, he has represented his country at many Olympiads, from 1986 onwards, and won an individual bronze medal at Turin in 2006. Miguel won international tournaments too, such as Las Palmas 1987 and 1988, Oviedo 1991, Pamplona 1991/92, 2nd at Leon 1992 (after Boris Gulko), 3rd at Chalkidiki 1992 (after Vladimir Kramnik and Joel Lautier), Lisbon Zonal 1993, and 2nd at Wijk aan Zee 1993 (after Anatoly Karpov). He kept winning during the latter part of the nineties, including Linares (MEX) 1994, Linares (ESP) Zonal 1995, Madrid 1996, and Pamplona 1997/98. Some Palmares! The ultimate goal of a chess player is to checkmate the opponent. We know that – especially at the higher level – it's rare to see someone get checkmated over the board, but when it happens, there is a sense of fulfillment that only a checkmate can give. To learn how to checkmate an opponent is not an easy task, though. Checkmating is probably the only phase of the game that can be associated with mathematics. Maths and checkmating have one crucial thing in common: patterns! GM Miguel is not going to show us a long list of checkmate examples: the series intends to teach patterns. -

UIL Text 111212

UIL Chess Puzzle Solvin g— Fall/Winter District 2016-2017 —Grades 4 and 5 IMPORTANT INSTRUCTIONS: [Test-administrators, please read text in this box aloud.] This is the UIL Chess Puzzle Solving Fall/Winter District Test for grades four and five. There are 20 questions on this test. You have 30 minutes to complete it. All questions are multiple choice. Use the answer sheet to mark your answers. Multiple choice answers pur - posely do not indicate check, checkmate, or e.p. symbols. You will be awarded one point for each correct answer. No deductions will be made for incorrect answers on this test. Finishing early is not rewarded, even to break ties. So use all of your time. Some of the questions may be hard, but all of the puzzles are interesting! Good luck and have fun! If you don’t already know chess notation, reading and referring to the section below on this page will help you. How to read and answer questions on this test Piece Names Each chessman can • To answer the questions on this test, you’ll also be represented need to know how to read chess moves. It’s by a symbol, except for the pawn. simple to do. (Figurine Notation) K King Q • Every square on the board has an “address” Queen R made up of a letter and a number. Rook B Bishop N Knight Pawn a-h (We write the file it’s on.) • To make them easy to read, the questions on this test use the figurine piece symbols on the right, above. -

More About Checkmate

MORE ABOUT CHECKMATE The Queen is the best piece of all for getting checkmate because it is so powerful and controls so many squares on the board. There are very many ways of getting CHECKMATE with a Queen. Let's have a look at some of them, and also some STALEMATE positions you must learn to avoid. You've already seen how a Rook can get CHECKMATE XABCDEFGHY with the help of a King. Put the Black King on the side of the 8-+k+-wQ-+( 7+-+-+-+-' board, the White King two squares away towards the 6-+K+-+-+& middle, and a Rook or a Queen on any safe square on the 5+-+-+-+-% same side of the board as the King will give CHECKMATE. 4-+-+-+-+$ In the first diagram the White Queen checks the Black King 3+-+-+-+-# while the White King, two squares away, stops the Black 2-+-+-+-+" King from escaping to b7, c7 or d7. If you move the Black 1+-+-+-+-! King to d8 it's still CHECKMATE: the Queen stops the Black xabcdefghy King moving to e7. But if you move the Black King to b8 is CHECKMATE! that CHECKMATE? No: the King can escape to a7. We call this sort of CHECKMATE the GUILLOTINE. The Queen comes down like a knife to chop off the Black King's head. But there's another sort of CHECKMATE that you can ABCDEFGH do with a King and Queen. We call this one the KISS OF 8-+k+-+-+( DEATH. Put the Black King on the side of the board, 7+-wQ-+-+-' the White Queen on the next square towards the middle 6-+K+-+-+& and the White King where it defends the Queen and you 5+-+-+-+-% 4-+-+-+-+$ get something like our next diagram. -

Dvoretsky Lessons 12

The Instructor Tragicomedies in Pawn Endgames “Pawn endgames are rare birds in practice. Players avoid them, because they do not like them, because they do not understand them. It’s certainly no secret that pawn endings are ‘terra incognita’ - even for many masters, right up to the level of grandmasters and world champions.” N. Grigoriev Herewith, I offer proof that these words, spoken by a famous expert on pawn endings, are true. Without commentary, I give below the final moves of some actual games, and offer the readers the chance to comment on them, to uncover all the mistakes committed by both players. The endgames you will be dealing with here are not all that difficult; but still, the players on both sides have The provided you with plenty of opportunities for critical commentary. 1...Kf8 2. Qf5+ Qxf5 3. gf Kg7 4. c4 f3 5. h6+ Kxh6 6. c5 dc 7. f6 Kg6 Instructor White resigned. Mark Dvoretsky 1...g5 2. Kf3 Kd5 3. c6 Kd6 4. Ke4 a6 5. ba Kxc6 6. Kf3 Kb6 7. h4 gh 8. Kg4 Kxa6 9. Kxh4 Kb6 10. Kg4 Kc6 11. h4 Kd6. White resigned. file:///C|/Cafe/Dvoretsky/dvoretsky.htm (1 of 9) [9/11/2001 7:09:02 AM] The Instructor 1. Kh7 Kf7 2. Kh8 Kf8 3. g5. Black resigned. 1. Kg5 Kf8 2. Kxf5 Kf7 3. Kg4 Kf6 4. Kf4 Kf7 5. Kf5 Ke7 6. Ke5 Kf7 7. Kd6 Kf6 8. Kd7 Kf7 9. h6 Kg6 10. f4 Kf7 11. f5 Kf6 Drawn Gazic - Petursson European Junior Championship, Groningen 1978/79 The draw is obvious after 1...Kh8! Black mistakenly allowed the trade of queens. -

Chess-Training-Guide.Pdf

Q Chess Training Guide K for Teachers and Parents Created by Grandmaster Susan Polgar U.S. Chess Hall of Fame Inductee President and Founder of the Susan Polgar Foundation Director of SPICE (Susan Polgar Institute for Chess Excellence) at Webster University FIDE Senior Chess Trainer 2006 Women’s World Chess Cup Champion Winner of 4 Women’s World Chess Championships The only World Champion in history to win the Triple-Crown (Blitz, Rapid and Classical) 12 Olympic Medals (5 Gold, 4 Silver, 3 Bronze) 3-time US Open Blitz Champion #1 ranked woman player in the United States Ranked #1 in the world at age 15 and in the top 3 for about 25 consecutive years 1st woman in history to qualify for the Men’s World Championship 1st woman in history to earn the Grandmaster title 1st woman in history to coach a Men's Division I team to 7 consecutive Final Four Championships 1st woman in history to coach the #1 ranked Men's Division I team in the nation pnlrqk KQRLNP Get Smart! Play Chess! www.ChessDailyNews.com www.twitter.com/SusanPolgar www.facebook.com/SusanPolgarChess www.instagram.com/SusanPolgarChess www.SusanPolgar.com www.SusanPolgarFoundation.org SPF Chess Training Program for Teachers © Page 1 7/2/2019 Lesson 1 Lesson goals: Excite kids about the fun game of chess Relate the cool history of chess Incorporate chess with education: Learning about India and Persia Incorporate chess with education: Learning about the chess board and its coordinates Who invented chess and why? Talk about India / Persia – connects to Geography Tell the story of “seed”. -

Sample Pages

Dvoretsky’s Analytical Manual by Mark Dvoretsky Foreword by Karsten Müller 2013 Russell Enterprises, Inc. Milford, CT USA 1 Dvoretsky’s Analytical Manual © Copyright 2008, 2013 Mark Dvoretsky All Rights Reserved No part of this book may be used, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any manner or form whatsoever or by any means, electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. ISBN: 978-1-936490-74-5 First Edition 2008 Second Edition 2013 Published by: Russell Enterprises, Inc. P.O. Box 3131 Milford, CT 06460 USA http://www.russell-enterprises.com [email protected] Cover design by Janel Lowrance Translated from the Russian by Jim Marfia Photograph of Mark Dvoretsky by Carl G. Russell Printed in the United States of America 2 Table of Contents Foreword 4 Introduction 5 Signs, Symbols, and Abbreviations 10 Part 1 Immersion in the Position 11 Chapter 1 Combinative Fireworks 12 Chapter 2 Chess Botany – The Trunk 25 Chapter 3 Chess Botany – The Shrub 32 Chapter 4 Chess Botany – Variational Debris 38 Chapter 5 Irrational Complications 49 Chapter 6 Surprises in Calculating Variations 61 Chapter 7 More Surprises in Calculating Variations 69 Part 2 Analyzing the Endgame 85 Chapter 8 Two Computer Analyses 86 Chapter 9 Zwischenzugs in the Endgame 93 Chapter 10 Play like a Computer 98 Chapter 11 Challenging Studies 106 Chapter 12 Studies for Practical -

The Queen's Gambit

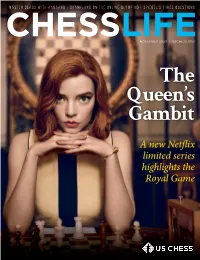

Master Class with Aagaard | Shankland on the Online Olympiad | Spiegel’s Three Questions NOVEMBER 2020 | USCHESS.ORG The Queen’s Gambit A new Netflix limited series highlights the Royal Game The United States’ Largest Chess Specialty Retailer 888.51.CHESS (512.4377) www.USCFSales.com EXCHANGE OR NOT UNIVERSAL CHESS TRAINING by Eduardas Rozentalis by Wojciech Moranda B0086TH - $33.95 B0085TH - $39.95 The author of this book has turned his attention towards the best Are you struggling with your chess development? While tool for chess improvement: test your current knowledge! Our dedicating hours and hours on improving your craft, your rating author has provided the most important key elements to practice simply does not want to move upwards. No worries ‒ this book one of the most difficult decisions: exchange or not! With most is a game changer! The author has identified the key skills that competitive games nowadays being played to a finish in a single will enhance the progress of just about any player rated between session, this knowledge may prove invaluable over the board. His 1600 and 2500. Becoming a strong chess thinker is namely brand new coverage is the best tool for anyone looking to improve not only reserved exclusively for elite players, but actually his insights or can be used as perfect teaching material. constitutes the cornerstone of chess training. THE LENINGRAD DUTCH PETROSIAN YEAR BY YEAR - VOLUME 1 (1942-1962) by Vladimir Malaniuk & Petr Marusenko by Tibor Karolyi & Tigran Gyozalyan B0105EU - $33.95 B0033ER - $34.95 GM Vladimir Malaniuk has been the main driving force behind International Master Tibor Karolyi and FIDE Master Tigran the Leningrad Variation for decades. -

Dvoretsky's Endgame Manual

Dvoretsky’s Endgame Manual Mark Dvoretsky Foreword by Artur Yusupov Preface by Jacob Aagaard 2003 Russell Enterprises, Inc. Milford, CT USA 1 Table of Contents Foreword 6 Preface 7 From the Author 8 Other Signs, Symbols, and Abbreviations 12 Chapter 1 PAWN ENDGAMES 13 Key Squares 13 Corresponding Squares 14 Opposition 14 Mined Squares 18 Triangulation 20 Other Cases of Correspondence 22 King vs. Passed Pawns 24 The Rule of the Square 24 Réti’s Idea 25 The Floating Square 27 Three Connected Pawns 28 Queen vs. Pawns 29 Knight or Center Pawn 29 Rook or Bishop’s Pawn 30 Pawn Races 32 The Active King 34 Zugzwang 34 Widening the Beachhead 35 The King Routes 37 Zigzag 37 The Pendulum 38 Shouldering 38 Breakthrough 40 The Outside Passed Pawn 44 Two Rook’s Pawns with an Extra Pawn on the Opposite Wing 45 The Protected Passed Pawn 50 Two Pawns to One 50 Multi-Pawn Endgames 50 Undermining 53 Two Connected Passed Pawns 54 Stalemate 55 The Stalemate Refuge 55 “Semi-Stalemate” 56 Reserve Tempi 57 Exploiting Reserve Tempi 57 Steinitz’s Rule 59 The g- and h-Pawns vs. h-Pawn 60 The f- and h-Pawns vs. h-Pawn 62 Both Sides have Reserve Tempi 65 Chapter 2 KNIGHT VS. PAWNS 67 1 King in the Corner 67 Mate 67 Drawn Positions 67 Knight vs. Rook Pawn 68 The Knight Defends the Pawn 70 Chapter 3 KNIGHT ENDGAMES 74 The Deflecting Knight Sacrifice 74 Botvinnik’s Formula 75 Pawns on the Same Side 79 Chapter 4 BISHOP VS. -

Chess Rules Ages 10 & up • for 2 Players

Front (Head to Head) Prints Pantone 541 Blue Chess Rules Ages 10 & Up • For 2 Players Contents: Game Board, 16 ivory and 16 black Play Pieces Object: To threaten your opponent’s King so it cannot escape. Play Pieces: Set Up: Ivory Play Pieces: Black Play Pieces: Pawn Knight Bishop Rook Queen King Terms: Ranks are the rows of squares that run horizontally on the Game Board and Files are the columns that run vertically. Diagonals run diagonally. Position the Game Board so that the red square is at the bottom right corner for each player. Place the Ivory Play Pieces on the first rank from left to right in order: Rook, Knight, Bishop, Queen, King, Bishop, Knight and Rook. Place all of the Pawns on the second rank. Then place the Black Play Pieces on the board as shown in the diagram. Note: the Ivory Queen will be on a red square and the black Queen will be on a black space. Play: Ivory always plays first. Players alternate turns. Only one Play Piece may be moved on a turn, except when castling (see description on back). All Play Pieces must move in a straight path, except for the Knight. Also, the Knight is the only Play Piece that is allowed to jump over another Play Piece. Play Piece Moves: A Pawn moves forward one square at a time. There are two exceptions to this rule: 1. On a Pawn’s first move, it can move forward one or two squares. 2. When capturing a piece (see description on back), a Pawn moves one square diagonally ahead. -

Chess Basics

NEWSLETTER Library: Jan-2003 Morals of Chess Feb-2003 Humor in Chess Feb 15th SCC Guidelines March 2003 The History of Chess Notation by Robert John McCrary The number of books on chess is greater the number of books on all other games combined. Yet, chess books would be few and far between if there were not an efficient way to record the moves of games. Chess notation is thus the special written" language" of chess players, making it possible for a single book to contain hundreds of games by great players, or thousands of opening variations. Surprisingly, however, chess notation was slow to evolve. As late as the early nineteenth century, many chess books simply wrote out moves in full sentences! As a result, very few of those early games before the 1800's were recorded and preserved in print, and published analysis was correspondingly limited. In Shakespeare's day, for example, the standard English chess book gave the move 2.Qf3 as follows: " Then the black king for his second draught brings forth his queene, and placest her in the third house, in front of his bishop's pawne." Can we imagine recording a full 40-move game with each move written out like that! Nevertheless, the great 18th century player and author Andre Philidor, in his highly influential chess treatise published in 1747, continued to write out moves as full sentences. One move might read, "The bishop takes the bishop, checking." Or the move e5 would appear as "King's pawn to adverse 4th." Occasionally Philidor would abbreviate something, but generally he liked to spell everything out. -

Art. I.—On the Persian Game of Chess

JOURNAL OF THE ROYAL ASIATIC SOCIETY. ART. I.— On the Persian Game of Chess. By K BLAND, ESQ., M.R.A.S. [Read June 19th, 1847.] WHATEVER difference of opinion may exist as to the introduction of Chess into Europe, its Asiatic origin is undoubted, although the question of its birth-place is still open to discussion, and will be adverted to in this essay. Its more immediate design, however, is to illustrate the principles and practice of the game itself from such Oriental sources as have hitherto escaped observation, and, especially, to introduce to particular notice a variety of Chess which may, on fair grounds, be considered more ancient than that which is now generally played, and lead to a theory which, if it should be esta- blished, would materially affect our present opinions on its history. In the life of Timur by Ibn Arabshah1, that conqueror, whose love of chess forms one of numerous examples among the great men of all nations, is stated to have played, in preference, at a more complicated game, on a larger board, and with several additional pieces. The learned Dr. Hyde, in his valuable Dissertation on Eastern Games2, has limited his researches, or, rather, been restricted in them by the nature of his materials, to the modern Chess, and has no further illustrated the peculiar game of Timur than by a philological Edited by Manger, "Ahmedis ArabsiadEe Vitae et Rernm Gestarum Timuri, qui vulgo Tamerlanes dicitur, Historia. Leov. 1772, 4to;" and also by Golius, 1736, * Syntagma Dissertationum, &c. Oxon, MDCCJ-XVII., containing "De Ludis Orientalibus, Libri duo." The first part is " Mandragorias, seu Historia Shahi.