Strengthening Trade Capacity for Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2016 Ghana Banking Survey How to Win in an Era of Mobile Money

2016 Ghana Banking Survey How to win in an era of mobile money August 2016 www.pwc.com/gh Contents A message from our CSP 2 A message from the Executive Secretary of Ghana Association of Bankers 4 Comments on 2016 Ghana Banking Survey 6 A message from our Tax Leader 8 1 How to win in an era of mobile money 10 2 Overview of the economy 26 3 Overview of the banking industry 32 4 Quartile analysis 36 5 Market share analysis 48 6 Profitability and efficiency 56 7 Return to shareholders 64 8 Liquidity 68 9 Asset quality 74 A List of participants 77 B Glossary of key financial terms, equations and ratios 78 C List of abbreviations 79 D Our profile 80 E Our leadership team 84 PwC 2016 Ghana Banking Survey 1 A message from our CSP for consumer banking. Besides, it offers in designing a practical and forward huge cheap deposits that banks could looking regulation that will streamline use to create money in the economy. It operations in the mobile money market. is against this backdrop that we focused This will require extensive consultation this year’s banking survey on “How to win locally and leveraging the experience of in an era of mobile money”. other countries such as Kenya that are advanced in the delivery of the service. Unlike the 2015 banking survey that sought responses from bank executives In addition to regulations and as well as bank customers, this year’s partnerships, the other critical success survey was based on responses from factors which we discussed with bank bank executives only. -

2014 IAFFE Annual Conference Program

1 INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR FEMINIST ECONOMICS 23rd IAFFE Annual Conference Women’s Economic Empowerment and the New Global Development Agenda University of Ghana Legon, Ghana June 27-29th, 2014 A Special Thank You to Our Sponsors We are very grateful for the support of these and other institutions, organizations and individuals that make our work possible Friedrich-•Ebert-•Stiftung (FES) - Berlin (Germany) * Friedrich-•Ebert-•Stiftung (FES) – Ghana * The Ford Foundation * Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation * Institute of Statistical, Social and Economic Research (ISSER) * University of Ghana, Department of Economics * University of Ghana, Centre for Gender Studies and Advocacy (CEGENSA) * University of Ghana * IAFFE is also grateful for the continued support of the University of Nebraska – Lincoln, Department of Economics, Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources, Department of Agricultural Economics 2 Our sincere appreciation goes out to the individuals that have worked so diligently to make this conference a success Abena Oduro, Dzodzi Tsikata, On-Site Coordinators Ashley van Waes, IAFFE Conference Coordinator and Journal Staff, Melisa Sanchez, Christine Cox, Polly Morrice, and Anne Dayton The conference events, unless otherwise noted, are located in the following building: Legon Center for International Affairs and Diplomacy FRIDAY, JUNE 27th 8:00 am – 5:00 pm Registration Foyer 8:00 – 10:00 am Committee Meetings (rooms not assigned) 10:15 am – 12:15 pm Welcome and Opening Plenary Great Hall Women's Rights Movement -

Trang 1/ 13 TERMS and CONDITIONS

“REFER CITI CARD, GET PREMIUM GIFTS – PERIOD 3/2021” PROGRAM (Effective from Sep 16th, 2021) TERMS AND CONDITIONS 1. Program Scope The “Refer Citi Card, Get Premium Gifts – Period 3/2021” Program (“the Program”) is applicable at Ha Noi and Ho Chi Minh City for existing primary card members of Citi PremierMiles card or Citi Cash Back card or Citi Rewards card or Citi Simplicity+ card or Lazada Citi Platinum card who refer their friends to apply for a Citi PremierMiles card or Citi Cash Back card or Citi Rewards card or Citi Simplicity+ card during the Program Period. 2. Program Period Sep 16th, 2021 to Jan 15th, 2022 (both days inclusive). 3. Promotion scheme 3.1. Within the program period, Eligible referrer will receive Cash Back and Tier rewards for each and multiple successful referrals, details as following: Successful Cash Back Tier Rewards Referrals 1 500,000 VND 2 1,000,000 VND 3 1,500,000 VND Tier 1: GotIt e-voucher valued VND 4 2,000,000 VND 2,000,000 5 2,500,000 VND 6 3,000,000 VND 7 3,500,000 VND Tier 2: AccorPlus Explorer 8 4,000,000 VND membership valued VND 6,000,000 9 4,500,000 VND 10 5,000,000 VND 11 5,500,000 VND Issued by Citibank Vietnam Page 1 of 6 12 6,000,000 VND Tier 3: Apple Watch SE 44mm GPS 13 6,500,000 VND valued VND 9,990,000 14 7,000,000 VND 15+ 7,500,000 VND Special: Apple 11-inch iPad Pro Wi-Fi 128GB valued VND 21,990,000 Caps 7,500,000 VND Tier 1: 100 gifts Tier 2: 50 gifts Tier 3: 30 gifts Special: 20 gifts Note: In all situations, a Referrer who satisfies all the terms and conditions of the program will receive maximum VND 7,500,000 cash back. -

Bradley C Resume

BRADLEY C. LALONDE Co-Founder and Managing Partner Vietnam Partners LLC Hanoi, Vietnam email: [email protected] mobile: +84-90-810-6518 (Vietnam) +1-917-991-9109 (global) PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE: Over 25 year career in investment and corporate banking in multiple countries, spanning the United States, Europe, Middle East, Africa and Asia. Over 15 years experience in general management of Citibank franchises encompassing credit, marketing, operations and technology and treasury activities. Built start up franchises into profitable and well controlled businesses in Turkey, Tunisia and Vietnam. Key competences are marketing, credit and risk management , people management, particularly hiring, training and developing staff in marketing and risk management skills. A frequent guest lecturer in selling skills, marketing and risk management in Citibank training programs. In addition, significant professional experience in strategic planning, developing a business model to service the non-bank financial institutions industry, corporate audit for commercial lending and leasing in the United States, and Private Equity. Senior Credit Officer of Citigroup. Awarded distinguished order of the Republic from President of Tunisia for contributions to banking system(1993). Chairman of the American Chamber of Commerce in Hanoi, Vietnam(1996-1998). Numerous board seats on various trade and community organizations. PRESENT: Partner and Co-Founder of Vietnam Partners, New York. Since October 03 to present. An Investment Bank serving the Vietnamese government and businesses in Vietnam. Investing capital, raising capital and providing financial advise. Head office in New York City and representative office in Hanoi, Vietnam. Notable achievements over the last 5 years. Established 50:50 joint venture fund management company with Bank for Development and Investment in Vietnam( BIDV). -

Download Date 28/09/2021 19:08:59

Ghana: From fragility to resilience? Understanding the formation of a new political settlement from a critical political economy perspective Item Type Thesis Authors Ruppel, Julia Franziska Rights <a rel="license" href="http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/3.0/"><img alt="Creative Commons License" style="border-width:0" src="http://i.creativecommons.org/l/by- nc-nd/3.0/88x31.png" /></a><br />The University of Bradford theses are licenced under a <a rel="license" href="http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/">Creative Commons Licence</a>. Download date 28/09/2021 19:08:59 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10454/15062 University of Bradford eThesis This thesis is hosted in Bradford Scholars – The University of Bradford Open Access repository. Visit the repository for full metadata or to contact the repository team © University of Bradford. This work is licenced for reuse under a Creative Commons Licence. GHANA: FROM FRAGILITY TO RESILIENCE? J.F. RUPPEL PHD 2015 Ghana: From fragility to resilience? Understanding the formation of a new political settlement from a critical political economy perspective Julia Franziska RUPPEL Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities University of Bradford 2015 GHANA: FROM FRAGILITY TO RESILIENCE? UNDERSTANDING THE FORMATION OF A NEW POLITICAL SETTLEMENT FROM A CRITICAL POLITICAL ECONOMY PERSPECTIVE Julia Franziska RUPPEL ABSTRACT Keywords: Critical political economy; electoral politics; Ghana; political settle- ment; power relations; social change; statebuilding and state formation During the late 1970s Ghana was described as a collapsed and failed state. In contrast, today it is hailed internationally as beacon of democracy and stability in West Africa. -

Statement by Former President John Dramani

STATEMENT BY FORMER PRESIDENT JOHN DRAMANI MAHAMA ON CAMPAIGN TEAM Today, I am proud to introduce the team that will manage my flagbearership campaign to lead the National Democratic Congress (NDC) to victory in the 2020 presidential election. I am fortunate to have the backing of such an impressive group of hardworking people, who are as committed as I am to the road ahead. Their combination of years of experience, vision, energy and new ideas is inspiring and I am excited to work with them. We are visiting our delegates in the regions to hear what they have to say, listen to their concerns as well as their views on how we can move the party and Ghana forward. Please join me in welcoming the team onboard. CAMPAIGN MANAGER Ambassador Daniel Ohene Agyekum is a former Ambassador to the United States of America. He has also held various ministerial positions, including former Ashanti Regional Minister, Minister for Chieftaincy Affairs and other senior level public appointments. He is the immediate-past Chairman of COCOBOD. Previously, he served as Regional Chairman of the National Democratic Congress (NDC) in the Ashanti Region. DEPUTY CAMPAIGN MANAGER (I) Nii Vandepuye Djangmah is a former Deputy Regional Minister for the Greater Accra Region. He is also a former Regional Secretary with strong expertise in leadership training and grassroots mobilization. He is also 2011 GAME Campaign Coordinator. DEPUTY CAMPAIGN MANAGER (II) Dr. Godfred Seidu Jasaw holds a PhD in Sustainability Science from the United Nations University, Tokyo and has a Masters in Social Policy Planning in Developing Countries from the London School of Economics. -

Competitive Clientelism, Easy Financing and Weak Capitalists: the Contemporary PAPER Political Settlement in Ghana

DIIS WORKDIIS WORKINGING PAPER PAPER2011:27 Competitive Clientelism, Easy Financing and Weak Capitalists: The Contemporary PAPER Political Settlement in Ghana Lindsay Whitfield DIIS Working Paper 2011:27 NG I WORK 1 DIIS WORKING PAPER 2011:27 LINDSAY WHITFIELD is Associate Professor in Global Studies at Roskilde University, Denmark e-mail: [email protected] ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author wishes to thank Adam Moe Fejerskov for research assistance. DIIS Working Papers make available DIIS researchers’ and DIIS project partners’ work in progress towards proper publishing. They may include important documentation which is not necessarily published elsewhere. DIIS Working Papers are published under the responsibility of the author alone. DIIS Working Papers should not be quoted without the express permission of the author. DIIS WORKING PAPER 2011:27 © The author and DIIS, Copenhagen 2011 Danish Institute for International Studies, DIIS Strandgade 56, DK-1401 Copenhagen, Denmark Ph: +45 32 69 87 87 Fax: +45 32 69 87 00 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.diis.dk Cover Design: Carsten Schiøler Layout: Ellen-Marie Bentsen Printed in Denmark by Vesterkopi AS ISBN: 978-87-7605-476-2 Price: DKK 25.00 (VAT included) DIIS publications can be downloaded free of charge from www.diis.dk 2 DIIS WORKING PAPER 2011:27 DIIS WORKING PAPER SUB-SERIES ON ELITES, PRODUCTION AND POVERTY This working paper sub-series includes papers generated in relation to the research programme ‘Elites, Production and Poverty’. This collaborative research programme, launched in 2008, brings together research institutions and universities in Bangladesh, Denmark, Ghana, Mozambique, Tanzania and Uganda and is funded by the Danish Consultative Research Committee for Development Research. -

Vietnam Global Depositary Notes (Gdns) Issuance & Cancellation Guide GDN List / Vietnamese Bonds

Depositary Receipt Services August 2015 Vietnam Global Depositary Notes (GDNs) Issuance & Cancellation Guide GDN List / Vietnamese Bonds Coupon Maturity Date Local ISIN GDN ISIN 144A GDN ISIN REGS 12.300% 6/20/2016 VNTD11160403 US92670LAH24 XS1247495903 12.50% 7/25/2016 VNTD11160502 US92670LAJ89 XS1247502377 12.40% 9/6/2016 VNTD11160544 US92670LAK52 XS1247503268 7.60% 10/31/2016 VNTD13160195 US92670LAL36 XS1247505396 10.80% 4/15/2017 VNTD12170369 US92670LBA61 XS1247507095 9.50% 6/15/2017 VNTD12170385 US92670LAM19 XS1247509034 9.30% 1/15/2018 VNTD13180219 US92670LAN91 XS1247509620 8.20% 1/15/2019 VNTD14190811 US92670LAP40 XS1247511014 7.90% 2/15/2019 VNTD14190829 US92670LAQ23 XS1247511527 6.00% 1/15/2020 VNTD15202565 US92670LAR06 XS1247512681 5.40% 1/31/2020 VNTD15202599 US92670LAS88 XS1247513499 5.30% 2/15/2020 VNTD15202607 US92670LAT61 XS1247514208 5.20% 2/28/2020 VNTD15202615 US92670LAU35 XS1247515601 8.70% 5/31/2024 VNTD14240921 US92670LAV18 XS1247516328 8.80% 3/15/2029 VNTD14290942 US92670LAW90 XS1247516674 7.60% 1/31/2030 VNTD15302589 US92670LAX73 XS1247517219 7.50% 2/28/2030 VNTD15302878 US92670LAY56 XS1247517565 7.20% 3/15/2030 VNTD15302886 US92670LAZ22 XS1247518530 Ratio for GDN Trading & Settlement Purposes • 1 Vietnam GDN = VND 100,000 nominal amount of Local Vietnamese Government Bonds 1 Vietnam GDN Issuance Process 1. On S/D, International Broker-Dealer sends instructs its local custodian (MT542 - DF Instruction) for the delivery of Vietnamese bonds to “Citibank NY GDN safekeeping account” at Citibank Vietnam including the following information: International Investor a) Counterparty: Citibank, N.A. – GDN depositary b) Local Vietnamese Bonds quantity & ISIN, c) GDN quantity & ISIN International Broker-Dealer d) GDN settlement instructions (DTC participant+ any sub-account # or other relevant reference). -

APEC Meeting Documents

Participant List (GFPN 03/2009A) APEC Workshop: Best Practices in Microfinance 7-8 April 2011, Hanoi, Vietnam PARTICIPANTS LIST Economy: BRUNEI DARUSSALAM S/N Title Name Position Organization Contacts ( Tel / HP / Fax / Email ) Rogayah binti Abdullah Community Development Officer Ministry of Culture, Youth and [email protected] Sports Norzaridah binti Haji Community Development Officer Ministry of Culture, Youth and [email protected] Zainal Sports Economy: CHILE S/N Title Name Position Organization Contacts ( Tel / HP / Fax / Email ) Ms. Katia Makhlouf Advisor in SMEs Division Ministry of Economy [email protected] Ms. Viviana Paredes Head of Women work Area Women’s National Service of Chile (SERNAM) [email protected] Economy: CHINA S/N Title Name Position Organization Contacts ( Tel / HP / Fax / Email ) Mr. ZHANG Haiying Division director Department of Small and Medium T: 861.0682.05316 Enterprises, Ministry of Industry and F: 861.0660.17331 Information Technology [email protected] 4 S/N Title Name Position Organization Contacts ( Tel / HP / Fax / Email ) Mr. ZHANG Baiyin Expert Ministry of Industry and Information T: 861.0682.05325 Technology Software and Integrated F: 861.0660.17331 circuit Promotion Center [email protected] Economy: INDONESIA S/N Title Name Position Organization Contacts ( Tel / HP / Fax / Email ) Mrs. Ika Tejaningrum Senior Analyst, Head of Research & Central Bank of Indonesia T: 622.1381.7991 Development on Credit and SMEs F: 622.1351.8951 [email protected] Ms. Caroline Mangowal Research Unit Manager Microfinance Innovation Center for [email protected] Resources and Alternatives (MICRA) Economy: MALAYSIA S/N Title Name Position Organization Contacts ( Tel / HP / Fax / Email ) Mrs. -

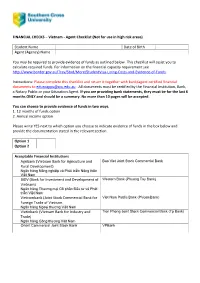

FINANCIAL CHECKS – Vietnam - Agent Checklist (Not for Use in High Risk Areas)

FINANCIAL CHECKS – Vietnam - Agent Checklist (Not for use in high risk areas) Student Name Date of Birth Agent (Agency) Name You may be required to provide evidence of funds as outlined below. This checklist will assist you to calculate required funds. For information on the financial capacity requirement see http://www.border.gov.au/Trav/Stud/More/StudentVisa-Living-Costs-and-Evidence-of-Funds. Instructions: Please complete this checklist and return it together with bank/agent certified financial documents to [email protected] . All documents must be certified by the Financial Institution, Bank, a Notary Public or your Education Agent. If you are providing bank statements, they must be for the last 6 months ONLY and should be a summary. No more than 10 pages will be accepted. You can choose to provide evidence of funds in two ways. 1. 12 months of funds option 2. Annual income option Please write YES next to which option you choose to indicate evidence of funds in the box below and provide the documentation stated in the relevant section. Option 1 Option 2 Acceptable Financial Institutions Agribank (Vietnam Bank for Agriculture and Bao Viet Joint Stock Commercial Bank Rural Development) Ngân hàng Nông nghiệp và Phát triển Nông thôn Việt Nam BIDV (Bank for Investment and Development of Western Bank (Phuong Tay Bank) Vietnam) Ngân hàng Thương mại Cổ phần Đầu tư và Phát triển Việt Nam Vietcombank (Joint Stock Commercial Bank for Viet Nam Public Bank (PVcomBank) Foreign Trade of Vietnam. Ngân hàng Ngoại thương Việt Nam Vietinbank (Vietnam -

Measuring the Intra-Household Distribution of Wealth in Ecuador

Measuring the Intra-Household Distribution of Wealth in Ecuador: Qualitative Insights and Quantitative Outcomes Carmen Diana Deere* and Zachary B. Catanzarite** Paper prepared for the URPE Session on Research Methods and Applications in Heterodox Economics, ASSA meetings, Philadelphia, PA, January 3-5, 2014. *Distinguished Professor of Latin American Studies and Food & Resource Economics, University of Florida **Statistical Data Analysis, Center for Latin American Studies, University of Florida Acknowledgements: The field research study reported on here was hosted by the Latin American Faculty of Social Sciences (FLACSO-Ecuador) and led by Deere, PI, and Jackeline Contreras, co-coordinator. Jennifer Twyman also participated in all of the field research and Mayra Aviles in the qualitative phase. Catanzarite has been responsible for data processing and statistical analysis. The field research and preliminary analysis was funded by the Dutch Foreign Ministry’s MDG3 Fund for Gender Equality as part of the Gender Asset Gap project, a comparative study of Ecuador, Ghana and India. The authors are grateful to the co-PIs of the comparative study, Cheryl Doss, Caren Grown, Abena D. Oduro and Hema Swaminatham, and other team members for permission to draw upon our joint work, and to the Vanguard Foundation and UN Women for financing the analytical work presented herein. 1 1. Introduction Among the concerns in the study of gender inequality is the role played by unequal access to resources within households. According to the bargaining power hypothesis, outcomes for women are often conditioned by the resources they command relative to others in the household, specifically their partners. Thus, women who own and control assets are expected to have a larger say in household decision-making than those who do not, and to use their bargaining power to secure outcomes more favorable to them and their children. -

(Casa) a Alger (Algerie), Du 10 Au 13 Decembre 2007

RAF/AFCAS/09 – Report October 2009 E AFRICAN COMMISSION ON AGRICULTURAL STATISTICS Twenty-first Session Accra, Ghana, 28 – 31 October 2009 Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Regional Office for Africa Accra, Ghana November 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS ORIGIN AND GOALS, PAST SESSIONS AND AFCAS (AFRICAN COMMISSION ON AGRICULTURAL STATISTICS) MEMBER COUNTRIES_________________________iii LIST OF MAIN RECOMMENDATIONS OF THE 21st SESSION ___________________iv I. INTRODUCTION ______________________________________________________ 1 I.1. Organization of the Session___________________________________________ 1 I.2. Opening Ceremony _________________________________________________ 1 I.3. Election of Officers__________________________________________________ 2 I.4. Adoption of Agenda _________________________________________________ 2 I.5. Closing ceremony __________________________________________________ 2 I.6. Vote of Thanks_____________________________________________________ 2 II. FAO ACTIVITIES IN FOOD AND AGRICULTURAL STATISTICS RELEVANT TO AFRICA REGION SINCE THE LAST SESSION OF THE AFRICAN COMMISSION ON AGRICULTURAL STATISTICS (Item 4) ______________________________________ 2 III. STATE OF FOOD AND AGRICULTURAL STATISTICS SYSTEMS IN THE REGION COUNTRIES (Item 5) ____________________________________________________ 4 IV. GLOBAL STRATEGY FOR IMPROVING AGRICULTURAL STATISTICS (Item 6) __ 5 V. IMPLEMENTATION OF THE NEW FEATURES OF THE WORLD PROGRAMME FOR CENSUS OF AGRICULTURE 2010 (Item 7) __________________________________