First Battle of Kernstown

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War Incorporated by Act of Congress

Grand Army of the Republic Posts - Historical Summary National GAR Records Program - Historical Summary of Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) Posts by State FLORIDA Prepared by the National Organization SONS OF UNION VETERANS OF THE CIVIL WAR INCORPORATED BY ACT OF CONGRESS No. Alt. Post Name Location County Dept. Post Namesake Meeting Place(s) Organized Last Mentioned Notes Source(s) No. PLEASE NOTE: The GAR Post History section is a work in progress (begun 2013). More data will be added at a future date. 000 (Department) N/A N/A FL Org. 9 July 1884 Ended 1945 Provisional Department organized in February 1868. Discontinued Beath, 1889; Carnahan, 1893; 28 January 1875. Provisional Department restored in early 1889. National Encampment Permanent Department of Florida organized 9 July 1884 with six Proceedings, 1945 Posts. The Department came to an end with the passing of Department Commader Logan J. Dyke, in 1945. 001 W. B. Woolsey Warrington Escambia FL Chart'd 1880 Post was present when the Department was reorganized in July Beath, 1889 1884. 002 James A. Garfield Pensacola / Escambia FL MG James Abram Garfield (1831- Post was present when the Department was reorganized in July Beath, 1889 Warrington 1881), Civil War leader and later 1884. US President (assassinated). 002 Stanton Lynn Haven Bay FL Org. 1911 Twenty -eight charter members. Biographical Sketches of Old Soldiers of Lynn Haven, 1920's 003 MAJ B. C. Lincoln Key West Monroe FL MAJ Benjamin Curtis Lincoln Post was present when the Department was reorganized in July Beath, 1889 (1840-1865), 2nd US Colored Inf., 1884. -

Welcome to “CHARGE

1 Welcome to “CHARGE!” From the Editor’s Desk This is the official newsletter of the Johnny Reb Gaming Society, an international association of miniature wargamers who use regimental-level rules such as the Johnny Reb gaming rules developed by John Hill. The newsletter will provide a quarterly forum for exchanging information regarding the rules, original wargaming scenarios written with JR in mind, and historical articles of general interest to the regimental ACW gamer. US membership in the society is $20 per year, which will partially cover the cost of assembling, printing, and mailing the newsletter. Dues are payable via money order or personal check, which must be made out to Deborah Mingus (society treasurer and secretary). Our mailing address and e-mail address are as follows: A photo of a 15mm miniature wargame I hosted The Johnny Reb Gaming Society for my kids over the holiday season. This 1383 Sterling Drive Christmas, we have been so blessed. As I write, York PA 17404 this, we are anxiously awaiting the birth of our [email protected] second grandson, another future battlefield tramping buddy for me! We welcome your submissions of articles, scenarios, advertising, and related information, This edition of Charge is the 22nd that Debi and as well as letters to the editor. The copyrighted I have produced, and we remain so very pleased name Johnny Reb is used by written permission and thankful at the response from the gaming of John Hill. community! So many of you have stepped up to Sample contributefile articles, scenarios, photographs, and Table of Contents advice, and we sincerely appreciate it! First Kernstown . -

Burial: Hillcrest Cemetery, Weiser, Washington, Idaho 116 Census: 1930, OR Multnomah Portland ED 112 Pg 4B Iii

===================== More About THOMAS BEAN: Burial: Hillcrest Cemetery, Weiser, Washington, Idaho 116 Census: 1930, OR Multnomah Portland ED 112 Pg 4B iii. ELNORA KIMBALL, b. Abt. 1904, Idaho. More About ELNORA KIMBALL: Census: 1910, ID Washington Hale ED 278 Pg 7B(See Father) iv. CARRIE KIMBALL, b. Abt. 1909, Idaho. More About CARRIE KIMBALL: Census: 1910, ID Washington Hale ED 278 Pg 7B(See Father) v. ALMA KIMBALL, b. Abt. 1911, Idaho. More About ALMA KIMBALL: Census: 1920, ID Adams Mesa ED 5 Pg 7B(See Father) vi. NATHAN KIMBALL, b. 06 Aug 1913, Idaho; d. 28 Mar 2004, Yakima, Yakima, Washington 117 . Notes for NATHAN KIMBALL: Yakima Herald Nathan L. 'Nate' Kimball Nathan L. "Nate" Kimball, 90, of Terrace Heights died Sunday, at Yakima Regional Medical and Cardiac Center. Mr. Kimball was born, raised and educated in Weiser, Idaho. In 1946, he started his own business, N.L. Kimball Construction and developed the company into a regionwide cement construction firm. Survivors include his wife, Alice G. Kimball of Yakima; his daughter, Theo Alexieff of Sequim, Wash.; one sister, Eva Wieneke; and five grandchildren. At his request, there will be no services. Family and friends are invited to a gathering at the home of Scott and Wanda Alexieff, 5600 Tumac Drive, Terrace Heights, 1-4 p.m. Friday. Langevin-Mussetter Funeral Home is in charge of the arrangements. ************ More About NATHAN KIMBALL: Census: 1920, ID Adams Mesa ED 5 Pg 7B(See Father) vii. EVA KIMBALL, b. Abt. 1916, Idaho; m. GEORGE WIENEKE, 09 Jun 1941, Weiser, Washington, Idaho 118 . More About EVA KIMBALL: Census: 1920, ID Adams Mesa ED 5 Pg 7B(See Father) 20. -

Stonewall Jackson's Valley Campaign

Civil War Book Review Spring 2009 Article 17 Shenandoah 1862: Stonewall Jackson's Valley Campaign Judkin Browning Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/cwbr Recommended Citation Browning, Judkin (2009) "Shenandoah 1862: Stonewall Jackson's Valley Campaign," Civil War Book Review: Vol. 11 : Iss. 2 . Available at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/cwbr/vol11/iss2/17 Browning: Shenandoah 1862: Stonewall Jackson's Valley Campaign Review Browning, Judkin Spring 2009 Cozzens, Peter Shenandoah 1862: Stonewall Jackson’s Valley Campaign. University of North Carolina Press, $35.00 hardcover ISBN 9780807832006 The Shenandoah Campaign and Stonewall Jackson In his fascinating monograph, Peter Cozzens, an independent scholar and author of The Darkest Days of the War: The Battles of Iuka and Corinth (1997), sets out to paint a balanced portrait of the 1862 Shenandoah Valley campaign and offer a corrective to previous one-sided or myth-enshrouded historical interpretations. Cozzens points out that most histories of the campaign tell the story exclusively from the perspective of Stonewall Jackson’s army, neglecting to seriously analyze the decision making process on the Union side, thereby simply portraying the Union generals as the inept foils to Jackson’s genius. Cozzens skillfully balances the accounts, looking behind the scenes at the Union moves and motives as well as Jackson’s. As a result, some historical characters have their reputations rehabilitated, while others who receive deserved censure, often for the first time. After a succinct and useful environmental and geographical overview of the Shenandoah region, Cozzens begins his narrative with the Confederate army during Jackson’s early miserable forays into the western Virginia Mountains in the winter of 1861, where he made unwise strategic decisions and ordered foolish assaults on canal dams near the Potomac River that accomplished nothing. -

A Defense of the 63Rd New York State Volunteer Regiment of the Irish Brigade Patricia Vaticano

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Master's Theses Student Research 5-2008 A defense of the 63rd New York State Volunteer Regiment of the Irish Brigade Patricia Vaticano Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/masters-theses Recommended Citation Vaticano, Patricia, "A defense of the 63rd New York State Volunteer Regiment of the Irish Brigade" (2008). Master's Theses. Paper 703. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A DEFENSE OF THE 63RD NEW YORK STATE VOLUNTEER REGIMENT OF THE IRISH BRIGADE By PATRICIA VATICANO Master of Arts in History University of Richmond 2008 Dr. Robert C. Kenzer, Thesis Director During the American Civil War, New York State’s irrepressible Irish Brigade was alternately composed of a number of infantry regiments hailing both from within New York City and from within and without the state, not all of them Irish, or even predominantly so. The Brigade’s core structure, however, remained constant throughout the war years and consisted of three all-Irish volunteer regiments with names corresponding to fighting units made famous in the annuals of Ireland’s history: the 69th, the 88th, and the 63rd. The 69th, or Fighting 69th, having won praise and homage for its actions at First Bull Run, was designated the First Regiment of the Brigade and went on to even greater glory in the Civil War and every American war thereafter. -

"The Regiment Bore a Conspicuous Part": a Brief History of the Eight Ohio Volunteer Infantry, Gibraltar Brigade, Army

Volume 6 Article 5 2007 "The Regiment Bore a Conspicuous Part": A Brief History of the Eight Ohio Volunteer Infantry, Gibraltar Brigade, Army of the Potomac Brian Matthew orJ dan Gettysburg College Class of 2009 Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/ghj Part of the Military History Commons, and the United States History Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Jordan, Brian Matthew (2007) ""The Regiment Bore a Conspicuous Part": A Brief History of the Eight Ohio Volunteer Infantry, Gibraltar Brigade, Army of the Potomac," The Gettysburg Historical Journal: Vol. 6 , Article 5. Available at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/ghj/vol6/iss1/5 This open access article is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "The Regiment Bore a Conspicuous Part": A Brief History of the Eight Ohio Volunteer Infantry, Gibraltar Brigade, Army of the Potomac Abstract On April 10, 1850, a sixteen year-old from Xenia, Ohio named Samuel Sexton copied a stanza of Epes Sargent’s poem, “A Life on the Ocean Wave,” into his notebook: A life on the ocean wave! A home on the rolling deep! Where the scattered waters rave, and the winds their revels keep! Like an eagle caged I pine, on this dull unchanging shore. Oh give me the flashing brine! The spray and the tempest roar! Before his death in New York City, July 11, 1896, Sexton would serve as the Assistant Surgeon of the Eighth Ohio Volunteers, his entire service in the field so strenuous that he was obliged to rest after the second year of combat. -

Stonewall Jackson's 1862 Valley Campaign, April 10-14, 2012

BGES Presents: Stonewall Jackson’s 1862 Valley Campaign, April 10-14, 2012 1862 dawned dark for the Confederates in Richmond—Federal inroads along the Atlantic Coast threatened lines of communications and industrial sites attempting to build a Confederate navy. In the west, George H. Thomas defeated Confederates at Mill Spring, Kentucky; Confederate hopes in Missouri had been dashed at Elkhorn Tavern. Most glaringly, a quiet but determined Union brigadier general named U.S. Grant sliced the state of Tennessee wide open with victories at Forts Henry and Donelson leading to the fall of Nashville. A Union flotilla filled to the gunwales with blue coated soldiers lurked in the Gulf of Mexico and would soon move against the south’s largest city, New Orleans, occupying it by May 1. In Virginia, the main southern army had unexpectedly abandoned its position in Northern Virginia and fallen back beyond the Rappahannock River while spies reported the movement of the federal army towards boats destined for the Virginia peninsula. In the Shenandoah Valley, a quiet Virginia Military Institute professor who had gained fame at Manassas in July 1861 commanded a Confederate force that was seemingly too small to accomplish anything noteworthy. That professor, Thomas J. Jackson, was an enigma whose strict sense of military propriety had caused him to offer his resignation when politicians interfered with his decision to push soldiers into the field during the harsh winter near Romney. Jackson stationed his force in the northern reaches of the Shenandoah Valley and would soon find himself embroiled in conflict with Brigadier General Richard Garnett on the heals of Stonewall’s only defeat at the battle of Kernstown. -

The Antietam and Fredericksburg

North :^ Carolina 8 STATE LIBRARY. ^ Case K3€X3Q£KX30GCX3O3e3GGG€30GeS North Carolina State Library Digitized by tine Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from State Library of North Carolina http://www.archive.org/details/antietamfredericOOinpalf THE ANTIETAM AND FREDERICKSBURG- Norff, Carof/na Staie Library Raleigh CAMPAIGNS OF THE CIVIL WAR.—Y. THE ANTIETAM AND FREDERICKSBURG BY FEAISrCIS WmTHEOP PALFEEY, BREVET BRIGADIER GENERAL, U. 8. V., AND FORMERLY COLONEL TWTENTIETH MASSACHUSETTS INFANTRY ; MEMBER OF THE MASSACHUSETTS HISTORICAL SOCIETF, AND OF THE MILITARY HIS- TORICAL SOCIETY OF MASSACHUSETTS. NEW YORK CHARLES SCRIBNEE'S SONS 743 AND 745 Broadway 1893 9.73.733 'P 1 53 ^ Copyright bt CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS 1881 PEEFAOE. In preparing this book, I have made free use of the material furnished by my own recollection, memoranda, and correspondence. I have also consulted many vol- umes by different hands. As I think that most readers are impatient, and with reason, of quotation-marks and foot-notes, I have been sparing of both. By far the lar- gest assistance I have had, has been derived from ad- vance sheets of the Government publication of the Reports of Military Operations During the Eebellion, placed at my disposal by Colonel Robert N. Scott, the officer in charge of the War Records Office of the War Department of the United States, F, W. P. CONTENTS. PAGE List of Maps, ..«.••• « xi CHAPTER I. The Commencement of the Campaign, .... 1 CHAPTER II. South Mountain, 27 CHAPTER III. The Antietam, 43 CHAPTER IV. Fredeeicksburg, 136 APPENDIX A. Commanders in the Army of the Potomac under Major-General George B. -

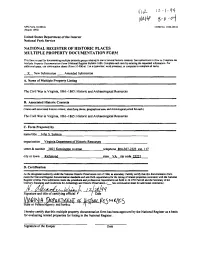

"4.+?$ Signature and Title of Certifying Official

NPS Fonn 10-900-b OMB No. 10244018 (March 1992) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES MULTIPLE PROPERTY DOCUMENTATIONFORM This form is used for documenting multiple pmpcny pups relating to one or several historic wnvxe. Sainsrmctions in How lo Complele the Mul1,ple Property D~mmmlationFonn (National Register Bullnin 16B). Compleveach item by entering the requested information. For addillanal space. use wntinuation shau (Form 10-900-a). Use a rypwiter, word pmarror, or computer to complete dl ivms. A New Submission -Amended Submission A. Name of Multiple Property Llstlng The Civil War in Virginia, 1861-1865: Historic and Archaeological Resources - B. Associated Historic Contexts (Name each acsociated historic conk* identifying theme, gmgmphid al and chronological Mod foreach.) The Civil War in Virginia, 1861-1865: Historic and Archaeological Resources - - C. Form Prepared by -- - nameltitle lohn S. Salmon organization Virginia De~artmentof Historic Resourceg smet & number 2801 Kensineton Avenue telephone 804-367-2323 em. 117 city or town -state VA zip code222l As ~ ~ -~~ - ~ ~~~ -~~ An~~~ ~~ sr amended I the duimated authoriw unda the National Hislaic~.~~ R*urvlion of 1%6. ~ hmbv~ ~~ ccrtih. ha this docummfation form , ~ ,~~ mauthe Nhlond Regutn docummunon and xu forth requ~rnncnufor the Istmg of related pmpnia wns~svntw~thihc~mund Rcglster crivna Thu submiu~onmsm ihc prcce4unl ~d pmfes~onalrcqutmnu uc lath in 36 CFR Pan M) ~d the Scsmar) of the Intenoh Standar& Md Guidelina for Alshoology and Historic Revnation. LSa wntinuation shafor additi01w.I wmmmu.) "4.+?$ Signature and title of certifying official I hereby certify that this multiple property documentation form has been approved by the National Register as a basis for evaluating related properties for listing in the National Register. -

The Civil War Journal of Mary Jane Chadick

INCIDENTS OF THE WAR The Civil War Journal of Mary Jane Chadick Nancy M. Rohr I nc idents o f th e W a r : T h e C iv il W a r J o u r n a l of M ar y J a n e C h a d ic k Edited and Annotated By N a n c y R o h r Copyright © 2005 by Nancy Rohr All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission by SilverThreads Publishing. ISBN: 0-9707368-1-9 SilverThreads Publishing 10012 Louis Drive Huntsville, Alabama 35803 Bibliography. Index. 1 .Chadick, Mary Jane, (1820-1905) 2. Diaries 3. Alabama History 4. Huntsville, AL 5. Civil War, 1861-1865— Narratives 6. United States—History—Civil War, 1861-1865—Personal Narratives, Confederate Women—Alabama—Diaries 7. Confederate States of America I. Nancy Rohr II. Madison County Historical Society Cover Illustration: Woodcut, taken from General Logan’s Headquarters, Huntsville, Alabama, Harper s Weekly, March 19, 1864. T a b l e o f C o n t e n t s Acknowledgments / v Editing Techniques / vi List of Illustrations/ viii List of Maps/ ix Introduction 1 Prologue 4 History of Huntsville and Madison County 4 History of the Cook Family 6 History of the Chadick Family 8 War 16 Incidents of the War 30 Federals in Huntsville April-September 1862 30 Civilians at War July 1863-May 1865 108 Epilogue 302 Reconstruction and Rebuilding 302 An Ending 326 Endnotes 332 Bibliography 358 Index 371 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This account could never have been published without the helpful and conscientious staff at the Huntsville, Alabama/ Madison County Public Library—Martin Towrey, Thomas Hutchens, John Hunt, Pat Carpenter, Bonnie Walters, Anne Miller, and Annewhite Fuller. -

First Kernstown/First Winchester Driving Tour

Battlefield Winchester Driving Tour AREA AT WAR First Kernstown 1862 Timeline & First Winchester Winter 1861-62 Confederate Gen. Thomas J. Stonewall Jackson’s “Stonewall” Jackson in winter headquarters in Winchester. 1862 Valley Campaign Winchester 4 March 1862 In early 1862 Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson, commander of Confederate 1 Jackson retires south, forces in the Valley, received his mandate from Gen. Joseph E. Johnston, commander Kernstown up the Valley, as Union forces of Richmond’s defenses: prevent Union forces from moving east to join Gen. George occupy Winchester. B. McClellan’s push on Richmond via the Virginia Peninsula. In one of military Strasburg history’s most brilliant campaigns, Jackson—with 18,000 men by mid-campaign— 23 March Front Royal Jackson is defeated at the kept three Union armies—almost 60,000 troops—at bay, helping to save the 3 First Battle of Kernstown. Confederacy’s capital from capture early in the war. April – May After pausing at modern-day First Battle of Kernstown – March 23 First Kernstown 1 Elkton, Jackson moves his army When Col. Turner Ashby informed McDowell out of the Valley to deceive 2 Federal forces and then returns Stonewall Jackson on March 22 that Front Royal 3 via rail through Staunton. Union forces were leaving the First Winchester 4 Valley and that only a token force Harrisonburg Cross Keys 5 8 May remained in the Winchester Port Republic 6 Jackson defeats area, Jackson marched his McDowell Federal forces under small army of 3,700 troops 5 Gen. John Frémont north from Strasburg. In fact, 2 6 at McDowell. -

The Texas Union Herald Colonel E

The Texas Union Herald Colonel E. E. Ellsworth Camp #18 Department of Texas Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War Volume iii, Number 9, September 2018 definitely rewrite things if necessary. Again, you do not Rattling Sabres have to be a Camp #18 member to submit material. by Continuing with finding photographs of the various Glen E. Zook Civil War battles fought in the month of the newsletter, here is the list, from the Hill’s Manual, of battles fought in I am trying some new features with this edition of September: The Texas Union Herald. The most obvious are the Battle of Boonville, Missouri, September 1, 1861; watermarks on each page. These watermarks are “clip art” Battle of Carniflex Ferry, Virginia, September 10, 1861; from the Internet which, from the information on the various Battle at Cheat Mountain Pass, Virginia, September 12 websites, are free to use without even having to credit the through September 17, 1861; Battle at Blue Mills, Missouri, sources. The use of these watermarks are to give a bit of September 17, 1861; Skirmish at Papinsville, Missouri, “pizzazz” to this publication. I would like to hear from the September 21.1861; Battle at Britton’s Lane, Tennessee, readers as to their opinion of these watermarks. September 1, 1862; Battle at Chantilly, Virginia, September In addition, I am trying to get back on schedule as 1, 1862; Battle at Washington, North Carolina, September to when this newsletter is actually published and is 6, 1862; Battle at Middletown, Maryland, September 12, distributed to the members of Camp #18 and to those 1862; Battle at South Mountain, Maryland, September 14, Department of Texas officials, National SUVCW officials, 1862; Battle of Harper’s Ferry, Virginia (now West Virginia), certain DUV members, and others who are on the September 12 through September 15, 1862; Battle of distribution list.