An Exploration of the French and American Schools of Classical Saxophone Sarah E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eastman School of Music, Thrill Every Time I Enter Lowry Hall (For- Enterprise of Studying, Creating, and Loving 26 Gibbs Street, Merly the Main Hall)

EASTMAN NOTESFALL 2015 @ EASTMAN Eastman Weekend is now a part of the University of Rochester’s annual, campus-wide Meliora Weekend celebration! Many of the signature Eastman Weekend programs will continue to be a part of this new tradition, including a Friday evening headlining performance in Kodak Hall and our gala dinner preceding the Philharmonia performance on Saturday night. Be sure to join us on Gibbs Street for concerts and lectures, as well as tours of new performance venues, the Sibley Music Library and the impressive Craighead-Saunders organ. We hope you will take advantage of the rest of the extensive Meliora Weekend programming too. This year’s Meliora Weekend @ Eastman festivities will include: BRASS CAVALCADE Eastman’s brass ensembles honor composer Eric Ewazen (BM ’76) PRESIDENTIAL SYMPOSIUM: THE CRISIS IN K-12 EDUCATION Discussion with President Joel Seligman and a panel of educational experts AN EVENING WITH KEYNOTE ADDRESS EASTMAN PHILHARMONIA KRISTIN CHENOWETH BY WALTER ISAACSON AND EASTMAN SCHOOL The Emmy and Tony President and CEO of SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Award-winning singer the Aspen Institute and Music of Smetana, Nicolas Bacri, and actress in concert author of Steve Jobs and Brahms The Class of 1965 celebrates its 50th Reunion. A highlight will be the opening celebration on Friday, featuring a showcase of student performances in Lowry Hall modeled after Eastman’s longstanding tradition of the annual Holiday Sing. A special medallion ceremony will honor the 50th class to commemorate this milestone. The sisters of Sigma Alpha Iota celebrate 90 years at Eastman with a song and ritual get-together, musicale and special recognition at the Gala Dinner. -

Download Article

International Conference on Arts, Design and Contemporary Education (ICADCE 2016) The Concertizing Clarinet in the Music of the 20th- 21st Centuries Yu Zhao Department of Musical Upbringing and Education Institute of Music, Theatre and Choreography Herzen State Pedagogical University of Russia Saint-Petersburg, Russia E-mail: [email protected] Abstract—The article deals with stating the problem of a clarinet concert of the 20-21 centuries (one should note in research in ontology of the genre of Clarinet Concert in 20-21 this regard S. E. Artemyev‟s full-featured thesis considering centuries. The author identifies genre variants of long forms the Concerto for clarinet and orchestra of the 18th century). for solo clarinet with orchestra or instrumental ensemble and proposes further steps in making such a research, as well. II. A SHORT GUIDE IN THE HISTORY OF THE CLARINET Keywords—instrumental concert; concertizing; concerto; CONCERT GENRE concert genres; genre diversity Studies in the executive mastership are connected with a research of the evolution of the genres of instrumental music. I. INTRODUCTION The initial period of genesis and development of clarinet concert is investigated widely. Contemporary music in its various genres has become in many aspects a subject of scrupulous studies in musicology. It is known that the most early is the composition of Our research deals with professional problematics of the Antonio Paganelli indicated by the author as Concerto per instrumental concert genre, viewed more narrowly, namely, Clareto (1733). Possibly, it was written for chalumeau, the connected with clarinet performance. instrument-predecessor of the clarinet itself. But, before this time clarinet was used as one of the concertizing instruments The purpose of this article is to identify the situation in the genre of Concerto Grosso, particularly by J. -

Alfred Desenclos

FRENCH SAXOPHONE QUARTETS Dubois Pierné Françaix Desenclos Bozza Schmitt Kenari Quartet French Saxophone Quartets Dubois • Pierné • Françaix • Desenclos • Bozza • Schmitt Invented in Paris in 1846 by Belgian-born Adolphe Sax, conductor of the Concerts Colonne series in 1910, Alfred Desenclos (1912-71) had a comparatively late The Andante et Scherzo, composed in 1943, is the saxophone was readily embraced by French conducting the world première of Stravinsky’s ballet The start in music. During his teenage years he had to work to dedicated to the Paris Quartet. This enjoyable piece is composers who were first to champion the instrument Firebird on 25th June 1910 in Paris. support his family, but in his early twenties he studied the divided into two parts. A tenor solo starts the Andante through ensemble and solo compositions. The French Pierné’s style is very French, moving with ease piano at the Conservatory in Roubaix and won the Prix de section and is followed by a gentle chorus with the other tradition, expertly demonstrated on this recording, pays between the light and playful to the more contemplative. Rome in 1942. He composed a large number of works, saxophones. The lyrical quality of the melodic solos homage to the élan, esprit and elegance delivered by this The Introduction et variations sur une ronde populaire which being mostly melodic and harmonic were often continues as the accompaniment becomes busier. The unique and versatile instrument. was composed in 1936 and dedicated to the Marcel Mule overlooked in the more experimental post-war period. second section is fast and lively, with staccato playing and Pierre Max Dubois (1930-95) was a French Quartet. -

Heralding a New Enlightenment

Peculiarities of Clarinet Concertos Form-Building in the Second Half of the 20th Century and the Beginning of the 21st Century Marina Chernaya and Yu Zhao* Abstract: The article deals with clarinet concertos composed in the 20th– 21st centuries. Many different works have been created, either in one or few parts; the longest concert that is mentioned has seven parts (by K. Meyer, 2000). Most of the concertos have 3 parts and the fast-slowly-fast kind of structure connected with the Italian overture; sometimes, the scheme has variants. Our question is: How does the concerto genre function during this period? To answer, we had to search many musical compositions. Sometimes the clarinet is accompanied by orchestra, other times it is surrounded by an ensemble of instruments. More than 100 concertos were found and analyzed. Examples of such concertos were written by C. Nielsen, P. Boulez, J. Adams, C. Debussy, M. Arnold, A. Copland, P. Hindemith, I. Stravinsky, S. Vassilenko, and the attention in the article is focused on them. A special complete analysis is made as regards “Domaines” for clarinet and 21 instruments divided in 6 groups, by Pierre Boulez that had a great role for the concert routine, based on the “aleatoric” principle. The conclusions underline the significant development of the clarinet concerto genre in the 20th -21st centuries, the high diversity of the compositions’ structures, the considerable expressiveness and technicality together with the soloist’s part in the expressive concertizing (as a rule). Further studies suggest the analysis of stylistic and structural peculiarities of the found compositions that are apparently to win their popularity with performers and listeners. -

(Pdf) Download

ATHANASIOS ZERVAS | BIOGRAPHY BRIEF BIOGRAPHY ATHANASIOS ZERVAS is a prolific composer, theorist, performer, conductor, teacher, and scholar. He holds a DM in composition and a MM in saxophone performance from Northwestern University, and a BA in music from Chicago State University. He studied composition with Frank Garcia, M. William Karlins, William Russo, Stephen Syverud, Alan Stout, and Jay Alan Yim; saxophone with Frederick Hemke, and Wayne Richards; jazz saxophone and improvisation with Vernice “Bunky” Green, Joe Daley, and Paul Berliner. Dr. Athanasios Zervas is an Associate Professor of music theory-music creation at the University of Macedonia in Thessaloniki Greece, Professor of Saxophone at the Conservatory of Athens, editor for the online theory/composition journal mus-e-journal, and founder of the Athens Saxophone Quartet. COMPLETE BIOGRAPHY ATHANASIOS ZERVAS is a prolific composer, theorist, performer, conductor, teacher, and scholar. He has spent most of his career in Chicago and Greece, though his music has been performed around the globe and on dozens of recordings. He is a specialist on pitch-class set theory, contemporary music, composition, orchestration, improvisation, music of the Balkans and Middle East, and traditional Greek music. EDUCATION He holds a DM in composition and an MM in saxophone performance from Northwestern University, and a BA in music from Chicago State University. He studied composition with M. William Karlins, William Russo, Stephen L. Syverud, Alan Stout, and Jay Alan Yim; saxophone with Frederick Hemke and Wayne Richards; jazz saxophone and improvisation with Vernice ‘Bunky’ Green, Joe Daley, and Paul Berliner; and jazz orchestration/composition with William Russo. RESEARCH + WRITING Dr. -

Extended Program Notes on a Saxophone Recital

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Research Papers Graduate School 5-2021 Extended Program Notes on a Saxophone Recital Ruben Rios [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/gs_rp Recommended Citation Rios, Ruben. "Extended Program Notes on a Saxophone Recital." (May 2021). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Research Papers by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EXTENDED PROGRAM NOTES ON A SAXOPHONE RECITAL by Rubén Ríos B.S., Conservatorio de Música de Puerto Rico, 2006 A Research Paper Submitted in PartiaL FulfiLLment of the Requirements for the Master of Music School of Music in the Graduate School Southern IlLinois University CarbondaLe May 2021 RESEARCH PAPER APPROVAL EXTENDED PROGRAM NOTES ON A SAXOPHONE RECITAL by Rubén Ríos A Research Paper Submitted in PartiaL FulfiLLment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Music in the fieLd of Music Approved by: Dr. Richard KeLLey, Chair Dr. James Reifinger Professor Edward Benyas Graduate School Southern IlLinois University CarbondaLe ApriL 8, 2021 AN ABSTRACT OF THE RESEARCH PAPER OF Ruben Rios, for the Master of Music degree in Music, presented on ApriL 8, 2021, at Southern IlLinois University CarbondaLe. TITLE: EXTENDED PROGRAM NOTES ON A SAXOPHONE RECITAL MAJOR PROFESSOR: Dr. Richard KeLLey The purpose of this research paper is to present some of the essentiaL pieces written for the saxophone by a group of composers from different countries, different musicaL backgrounds, and, most of aLL, different compositionaL styles. -

Guest Artist Recital 2012–13 Season Thursday 1 November 2012 117Th Concert Dalton Center Lecture Hall 11:00 A.M

Guest Artist Recital 2012–13 Season Thursday 1 November 2012 117th Concert Dalton Center Lecture Hall 11:00 a.m. THE U.S. ARMY FIELD BAND SAXOPHONE QUARTET Staff Sergeant Daniel Goff, Soprano Saxophone Sergeant First Class Brian Sacawa, Alto Saxophone Sergeant First Class Chris Blossom, Tenor Saxophone Staff Sergeant David Parks, Baritone Saxophone Ludwig van Beethoven String Quartet Opus 18, Number 1 1770–1827 I. Allegro con brio arr. SFC Chris Blossom II. Adagio affettuso ed appassionato III. Allegro molto IV. Allegro Philip Glass Saxophone Quartet b. 1937 I. II. III. IV. Bobby Streng Beat Down b. 1980 If the fire alarm sounds, please exit the building im m ediately. A ll other em ergencies w ill be indicated by spoken announcem ent within the seating area. The tornado safe area in Dalton Center is along the lockers in the brick hallway to your left as you exit the Lecture Hall. In any emergency, walk—do not run—to the nearest exit. Please turn off all cell phones and other electronic devices during the performance. Because of legal issues, any video or audio recording of this performance is prohibited without prior consent from the School of Music. Thank you for your cooperation. THE U.S. ARMY FIELD BAND SAXOPHONE QUARTET is an official ensemble of the Musical Ambassadors of the Army. The quartet performs a wide range of repertoire including transcriptions, standard saxophone quartet literature, jazz and popular arrangements, and contemporary and avant-garde music. The ensemble seeks to present a program that displays the numerous stylistic and musical capabilities of the saxophone. -

Unifying Elements of John Corigliano's

UNIFYING ELEMENTS OF JOHN CORIGLIANO'S ETUDE FANTASY By JANINA KUZMAS Undergraduate Diploma with honors, Sumgait College of Music, USSR, 1985 B. Mus., with the highest honors, Vilnius Conservatory, Lithuania, 1991 Performance Certificate, Lithuanian Academy of Music, 1993 M. Mus., Bowling Green State University, USA, 1995 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES School of Music We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA February 2002 © Janina Kuzmas 2002 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. ~':<c It CC L Department of III -! ' The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada Date J/difc-L DE-6 (2/88) ABSTRACT John Corigliano's Etude Fantasy (1976) is a significant and challenging addition to the late twentieth century piano repertoire. A large-scale work, it occupies a particularly important place in the composer's output of music for piano. The remarkable variety of genres, styles, forms, and techniques in Corigliano's oeuvre as a whole is also evident in his piano music. -

The Saxophone Symposium: an Index of the Journal of the North American Saxophone Alliance, 1976-2014

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2015 The aS xophone Symposium: An Index of the Journal of the North American Saxophone Alliance, 1976-2014 Ashley Kelly Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Kelly, Ashley, "The aS xophone Symposium: An Index of the Journal of the North American Saxophone Alliance, 1976-2014" (2015). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2819. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2819 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE SAXOPHONE SYMPOSIUM: AN INDEX OF THE JOURNAL OF THE NORTH AMERICAN SAXOPHONE ALLIANCE, 1976-2014 A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and AgrIcultural and MechanIcal College in partIal fulfIllment of the requIrements for the degree of Doctor of MusIcal Arts in The College of MusIc and DramatIc Arts by Ashley DenIse Kelly B.M., UniversIty of Montevallo, 2008 M.M., UniversIty of New Mexico, 2011 August 2015 To my sIster, AprIl. II ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My sIncerest thanks go to my committee members for theIr encouragement and support throughout the course of my research. Dr. GrIffIn Campbell, Dr. Blake Howe, Professor Deborah Chodacki and Dr. Michelynn McKnight, your tIme and efforts have been invaluable to my success. The completIon of thIs project could not have come to pass had It not been for the assIstance of my peers here at LouIsIana State UnIversIty. -

2018 OSU Saxophone Summit Schedule of Events Seretean Center for the Perfoming Arts January 27-28, 2018

2018 OSU Saxophone Summit Schedule of Events Seretean Center for the Perfoming Arts January 27-28, 2018 Schedule for Saturday, January 27 1:30 – 2:30 p.m. Summit Registration, OSU Music Lobby 2:30 – 3:20 p.m. Summit Registration, SCPA 123 Dr. Andrew Allen (Midwestern State University) Masterclass Saturday, January 27, 2018, 2:30PM Seretean Center for the Performing Arts – Room 123 Maï Ryo Noda Jacob Black, Oklahoma City University Aria Eugène Bozza AJ Nguyen, Oklahoma State University 3:30 – 4:45 p.m. OSU Saxophone Summit Recital #1, SCPA Concert Hall Alter Ego Georges Aperghis Tent of Miracles Martin Bresnick Geoffrey Deibel, Wichita State University Billie Jacob ter Veldhuis Christopher Barrick, University of Arkansas – Fort Smith Wings Joan Tower Eric Troiano, University of Arkansas String Quartet No. 12, Op.96 “American” Antonin Dvorák Meadowlark Quartet, Wichita State University Robert Hess, soprano saxophone Tyler Burgess, alto saxophone Bobby Kitchen, tenor saxophone Chris Agnew, baritone saxophone 5:00 – 5:50 p.m. Eric Troiano Masterclass, SCPA 123 Dr. Eric Troiano (University of Arkansas – Fayetteville) Masterclass Saturday, January 27, 2018, 5:00PM Seretean Center for the Performing Arts – Room 123 Concerto Henri Tomasi Mvt. I Andante et Allegro Sydney Pointer, Oklahoma State University Prélude, Cadence et Finale Alfred Desenclos Robert Hess, Wichita State University 7:30 – 9:00 p.m. OSU Saxophone Summit Recital #2, SCPA Concert Hall OSU Saxophone Summit Recital #2 Saturday, January 27, 2018, 7:30PM Seretean Center for the Performing Arts Concert Hall Olassimo (2017) François Rossé (b. 1945) Maï (1975) Ryo Noda (b. 1948) Andrew Allen (Midwestern State University), soprano and alto saxophone Wings Joan Tower Cradle Alexis Bacon Matthew Tracy (Southwest Oklahoma State University), alto saxophone Syrinx (1913) Claude Debussy (1862-1918) Hummingbrrd (2012/2016) Steven Bryant (b. -

A THEORETICAL ANALYSIS of SELECTED SOLO REPERTOIRE for SAXOPHONE by PAUL BONNEAU Keith T

A THEORETICAL ANALYSIS OF SELECTED SOLO REPERTOIRE FOR SAXOPHONE BY PAUL BONNEAU Keith T. Johnson, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2002 APPROVED: James Riggs, Major Professor and Chair James Gillespie, Co-Major Professor Gene Cho, Minor Professor John Scott, Chair of the Doctor of Musical Arts Committee, Dean of the School of Music C. Neal Tate, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies 1 Johnson, Keith T., A theoretical analysis of selected solo repertoire for saxophone by Paul Bonneau. Doctor of Musical Arts, (Saxophone Performance), August 2002, 118 pp., 98 musical examples, references, 44 titles. The primary purpose of this dissertation is to provide greater insight into the compositional design of Paul Bonneau’s Caprice en forme de valse solo pour saxophone and the Piece Concertante Dans L’Esprit “Jazz” pour saxophone alto et piano through a detailed analysis of the pieces. Paul Bonneau’s Caprice en forme de valse is a major work for saxophone. It has been referred to as one of the most technically demanding works in the classical saxophone repertoire. In addition, the Caprice has been transcribed for the flute, clarinet and bassoon. In fact, the Caprice has been designated as “one of the most musically cohesive unaccompanied works written for any wind instrument.” Bonneau’s Piece Concertante Dans L’Esprit “Jazz” is also an important work in the repertoire due to its high degree of virtuosity and unique fusion of traditional classical and jazz elements. The analysis process focuses initially on the fundamental elements of music. -

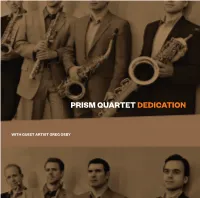

Prism Quartet Dedication

PRISM QUARTET DEDICATION WITH GUEST ARTIST GREG OSBY PRISM Quartet Dedication 1 Roshanne Etezady Inkling 1:09 2 Zack Browning Howler Back 1:09 3 Tim Ries Lu 2:36 4 Gregory Wanamaker speed metal organum blues 1:14 5 Renée Favand-See isolation 1:07 6 Libby Larsen Wait a Minute... 1:09 7 Nick Didkovksy Talea (hoping to somehow “know”) 1:06 8 Nick Didkovksy Stink Up! (PolyPrism 1) 1:06 9 Nick Didkovksy Stink Up! (PolyPrism 2) 1:01 10 Greg Osby Prism #1 (Refraction) 6:49 Greg Osby, alto sax solo 11 Donnacha Dennehy Mild, Medium-Lasting, Artificial Happiness 1:49 12 Ken Ueno July 23, from sunrise to sunset, the summer of the S.E.P.S.A. bus rides destra e sinistra around Ischia just to get tomorrow’s scatolame 1:20 13 Adam B. Silverman Just a Minute, Chopin 2:21 14 William Bolcom Scherzino 1:16 Matthew Levy Three Miniatures 15 Diary 2:05 16 Meditation 1:49 17 Song without Words 2:33 PRISM Quartet/Music From China 3 18 Jennifer Higdon Bop 1:09 19 Dennis DeSantis Hive Mind 1:06 20 Robert Capanna Moment of Refraction 1:04 21 Keith Moore OneTwenty 1:31 22 Jason Eckardt A Fractured Silence 1:18 Frank J. Oteri Fair and Balanced? 23 Remaining Neutral 1:00 24 Seeming Partial 3:09 25 Uncommon Ground 1:00 26 Incremental Change 1:49 27 Perry Goldstein Out of Bounds 1:24 28 Tim Berne Brokelyn 0:57 29 Chen Yi Happy Birthday to PRISM 1:24 30 James Primosch Straight Up 1:24 31 Greg Osby Prism #1 (Refraction) (alternate take) 6:49 Greg Osby, alto sax solo TOTAL PLAYING TIME 57:53 All works composed and premiered in 2004 except Three Miniatures, composed/premiered in 2006.