Pakistani Punjab, 1947 -1962

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sindh and Making of Pakistan Abstract Histori

Muhammad IqbalChawla* Fatima Riffat** A History of Sindh from a Regional Perspective: Sindh and Making of Pakistan Abstract Historical literature is full of descriptions concerning the life, thoughts and actions of main Muslim central leadership of India, like the role of Quaid-i-Azam in the creation of Pakistan. However enough literature on the topic, which can be easily accessed, especially in English, has not come to light on the efforts made by the political leadership of smaller provinces comprising today’s Pakistan during the Pakistan Movement. To fill the existing gap in historical literature this paper attempts to throw light on the contribution of Sindh provincial leadership. There are number of factors which have prompted the present author to focus on the province of Sindh and its provincial leadership. Firstly, the province of Sindh enjoys the prominence for being the first amongst all the Muslim-majority provinces of undivided India who have supported the creation of Pakistan. The Sind Provincial Muslim League had passed a resolution on 10 October, 1938, urging the right of political self-government for the two largest religious groups of India, Muslims and Hindus, even before the passage of the Lahore Resolution for Pakistan in 1940. Secondly, the Sindh Legislative Assembly followed suit and passed a resolution in support of Pakistan in March 1943. Thirdly, it was the first Muslim-majority province whose members of the Legislature opted to join Pakistan on 26 June 1947. Fourthly, despite personal jealousies, tribal conflicts, thrust for power, the political leadership in Sindh helped Jinnah to achieve Pakistan. But few leaders of Sindh not only left the Muslim League, denied the two nation theory and ended up with the idea of SindhuDesh(Independent Sindh vis a vis Pakistan).While investigating other dimensions of the Pakistan Movement and the role of Sindhi leaders this paper will also analyze the inconsistency of some of the Sindhi leaders regarding their position and ideologies. -

Centre-Province Relations, 1988-1993: a Case Study of the Punjab

Centre-Province Relations, 1988-1993: A Case Study of the Punjab A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY By Syed Tahir Hussain Bukhari Quaid-i-Azam University Islamabad, Pakistan 2016 Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Department of History Quaid-i-Azam University Islamabad, Pakistan 2016 DECLARATION I hereby declare that this thesis is the result of my individual research, and that it has not been submitted concurrently to any other university for any other degree. _____________________ Syed Tahir Hussain Bukhari DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY QUAID-I-AZAM UNIVERSITY ISLAMABAD Approval for Thesis Submission Dated: 2016 I hereby recommend the thesis prepared under my supervision by Syed Tahir Hussain Bukhari, entitled “Centre-Province Relations, 1988-1993: A Case Study of the Punjab” in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. __________________________ Dr. Razia Sultana Supervisor DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY QUAID-I-AZAM UNIVERSITY ISLAMABAD Dated: 2016 FINAL APPROVAL This is to certify that we have read the thesis submitted by Syed Tahir Hussain Bukhari, entitled “Centre-Province Relations, 1988-1993: A Case Study of the Punjab” and it is our judgment that this thesis is of sufficient standard to warrant acceptance by the Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. _ ____________________ -

The Role of Deobandi Ulema in Strengthening the Foundations of Indian Freedom Movement (1857-1924)

The Role of Deobandi Ulema in Strengthening the Foundations of Indian Freedom Movement (1857-1924) The Role of Deobandi Ulema in Strengthening the Foundations of Indian Freedom Movement (1857-1924) * Turab-ul-Hassan Sargana **Khalil Ahmed ***Shahid Hassan Rizvi Abstract The main objective of the present study is to explain the role of the Deobandi faction of scholars in Indian Freedom Movement. In fact, there had been different schools of thought who supported the Movement and their works and achievements cannot be forgotten. Historically, Ulema played a key role in the politics of subcontinent and the contribution of Dar ul Uloom Deoband, Mazahir-ul- Uloom (Saharanpur), Madrassa Qasim-ul-Uloom( Muradabad), famous madaris of Deobandi faction is a settled fact. Their role became both effective and emphatic with the passage of time when they sided with the All India Muslim League. Their role and services in this historic episode is the focus of the study in hand. Keywords: Deoband, Aligarh Movement, Khilafat, Muslim League, Congress Ulama in Politics: Retrospect: Besides performing their religious obligations, the religious ulema also took part in the War of Freedom 1857, similar to the other Indians, and it was only due to their active participation that the movement became in line and determined. These ulema used the pen and sword to fight against the British and it is also a fact that ordinary causes of 1857 War were blazed by these ulema. Mian Muhammad Shafi writes: Who says that the fire lit by Sayyid Ahmad was extinguished or it had cooled down? These were the people who encouraged Muslims and the Hindus to fight against the British in 1857. -

Copyright by Gwendolyn Sarah Kirk 2016

Copyright by Gwendolyn Sarah Kirk 2016 The Dissertation committee for Gwendolyn Sarah Kirk certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Uncivilized language and aesthetic exclusion: Language, power and film production in Pakistan Committee: _____________________________ Craig Campbell, Co-Supervisor _____________________________ Elizabeth Keating, Co-Supervisor _____________________________ Kamran Ali _____________________________ Patience Epps _____________________________ Ali Khan _____________________________ Kathleen Stewart _____________________________ Anthony Webster Uncivilized language and aesthetic exclusion: Language, power and film production in Pakistan by Gwendolyn Sarah Kirk, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December 2016 To my parents Acknowledgements This dissertation would not have been possible first and foremost without the kindness and generosity of the filmmakers I worked with at Evernew Studio. Parvez Rana, Hassan Askari, Z.A. Zulfi, Pappu Samrat, Syed Noor, Babar Butt, and literally everyone else I met in the film industry were welcoming and hospitable beyond what I ever could have hoped or imagined. The cast and crew of Sharabi, in particular, went above and beyond to facilitate my research and make sure I was at all times comfortable and safe and had answers to whatever stupid questions I was asking that day! Along with their kindness, I was privileged to witness their industry, creativity, and perseverance, and I will be eternally inspired by and grateful to them. My committee might seem large at seven members, but all of them have been incredibly helpful and supportive throughout my time in graduate school, and each of them have helped develop different dimensions of this work. -

Extrimist Movement in Kerala During the Struggle for Responsible Government

Vol. 5 No. 4 April 2018 ISSN: 2321-788X UGC Approval No: 43960 Impact Factor: 3.025 EXTRIMIST MOVEMENT IN KERALA DURING THE STRUGGLE FOR RESPONSIBLE GOVERNMENT Article Particulars: Received: 13.03.2018 Accepted: 31.03.2018 Published: 28.04.2018 R.T. ANJANA Research Scholar of History, University of Kerala, India Abstract Modern Travancore witnessed strong protests for civic amenities and representation in legislatures through the Civic Rights movement and Abstention movement during 1920s and early part of 1930s. Government was forced to concede reforms of far reaching nature by which representations were given to many communities in the election of 1937 and for recruitment a public service commission was constituted. But the 1937 election and the constitution of the Public Service Commission did not solve the question of adequate representation. A new struggle was started for the attainment of responsible government in Travancore which was even though led in peaceful means in the beginning, assumed extremist nature with the involvement of youthful section of the society. The participants of the struggle from the beginning to end directed their energies against a single individual, the Travancore Dewan Sir. C. P. Ramaswamy Iyer who has been considered as an autocrat and a blood thirsty tyrant On the other side the policies of the Dewan intensified the issues rather than solving it. His policy was dividing and rule, using the internal social divisions existed in Travancore to his own advantage. Keywords: civic amenities, Civic Rights, Public Service Commission, Travancore, Civil Liberties Union, State Congress In Travancore the demand for responsible government was not a new development. -

Religious Change and the Self in Muslim South Asia Since 1800

Religious Change and the Self in Muslim South Asia since 1800 Francis Robinson Royal Holloway, University of London In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries South Asian Muslims, along with Muslims elsewhere in the world, began to experience religious change of revolutionary significance. This change involved a shift in the focus of Muslim piety from the next world to this one. It meant the devaluing of a faith of contemplation on God's mysteries and of belief in His capacity to intercede for men on earth. It meant the valuing instead of a faith in which Muslims were increasingly aware that it was they, and only they, who could act to create a just society on earth. The balance which had long existed between the other-worldly and the this-worldly aspects of Islam was moved firmly in favour of the latter. This process of change has had many expressions: the movements of the Mujahidin, the Faraizis, Deoband, the Ahl-i Hadiths and Aligarh in the nineteenth century; and those of the Nadwat ul Ulama, the Tablighi Jamaat, the Jamaat-i Islami and the Muslim modernists in the twentieth. It has also been expressed in many subtle shifts in behaviour at saints' shrines and in the pious practice of many Muslims. Associated with this process of change was a shift in traditional Islamic knowledge away from the rational towards the revealed sciences, and a more general shift in the sources of inspiration away from the Iranian lands towards the Arab lands. There was also the adoption of print and the translations of authoritative texts into Indian languages with all their subsequent ramifications - among them the emergence of 2 a reflective reading of the scriptures and the development of an increasingly rich inner landscape. -

Role of the Muslim Anjumans for the Promotion of Education in the Colonial Punjab: a Historical Analysis

Bulletin of Education and Research December 2019, Vol. 41, No. 3 pp. 1-18 Role of the Muslim Anjumans for the Promotion of Education in the Colonial Punjab: A Historical Analysis Maqbool Ahmad Awan* __________________________________________________________________ Abstract This article highlightsthe vibrant role of the Muslim Anjumans in activating the educational revival in the colonial Punjab. The latter half of the 19th century, particularly the decade 1880- 1890, witnessed the birth of several Muslim Anjumans (societies) in the Punjab province. These were, in fact, a product of growing political consciousness and desire for collective efforts for the community-betterment. The Muslims, in other provinces, were lagging behind in education and other avenues of material prosperity. Their social conditions were also far from being satisfactory. Religion too had become a collection of rites and superstitions and an obstacle for their educational progress. During the same period, they also faced a grievous threat from the increasing proselytizing activities of the Christian Missionary societies and the growing economic prosperity of the Hindus who by virtue of their advancement in education, commerce and public services, were emerging as a dominant community in the province. The Anjumans rescued the Muslim youth from the verge of what then seemed imminent doom of ignorance by establishing schools and madrassas in almost all cities of the Punjab. The focus of these Anjumans was on both secular and religious education, which was advocated equally for both genders. Their trained scholars confronted the anti-Islamic activities of the Christian missionaries. The educational development of the Muslims in the Colonial Punjab owes much to these Anjumans. -

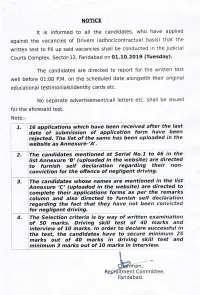

DRIVER LIST and NOTICE for WRITTEN EXAMINATION.Pdf

COMBINE Annexure-A Reject List of applications for the post of Driver August -2019 ( Ad-hoc) as received after due date 20/08/19 Date of Name of Receipt No. Father's / Husband Name Address of the candidate Contact No. Date of Birth Remarks Receipt Candidate Vill-Manesar, P.O Garth Rotmal Application 1 08/21/19 Yogesh Kumar Narender Kumar Teh- Ateli Distt Mohinder Garh 10/29/93 Received after State Haryana 20.08.2019 Khor PO Ateli Mandi Teh Ateli, Application 2 08/21/19 Pankaj Suresh Kumar 9818215697 12/20/93 Received after distt mahendergarh 20.08.2019 Amarjeet S/O Krishan Kumar Application 3 08/21/19 Amarjeet Kirshan Kumar 05/07/92 Received after VPO Bhikewala Teh Narwana 20.08.2019 121, OFFICER Colony Azad Application 4 08/21/19 Bhal Singh Bharat Singh nagar Rajgarh Raod, Near 08/14/96 Received after Godara Petrol Pump Hissar 20.08.2019 Vill Hasan, Teh- Tosham Post- Application 5 08/21/19 Rakesh Dharampal 10/15/97 Received after Rodhan (Bhiwani) 20.08.2019 VPO Jonaicha Khurd, Teh Application 6 08/21/19 Prem Shankar Roshan Lal Neemarana, dist Alwar 12/30/97 Received after (Rajasthan) 20.08.2019 VPO- Bhikhewala Teh Narwana Application 7 08/21/19 Himmat Krishan Kumar 09/05/95 Received after Dist Jind 20.08.2019 vill parsakabas po nagal lakha Application 8 08/21/19 Durgesh Kumar SHIMBHU DAYAL 09/05/95 Received after teh bansur dist alwar 20.08.2019 RZC-68 Nihar Vihar, Nangloi New Application 9 08/26/19 Amarjeet Singh Mohinder Singh 03/17/92 Received after Delhi 20.08.2019 Vill Palwali P.O Kheri Kalan Sec- Application 10 08/26/19 Rohit Sharma -

Remembering Partition: Violence, Nationalism and History in India

Remembering Partition: Violence, Nationalism and History in India Gyanendra Pandey CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Remembering Partition Violence, Nationalism and History in India Through an investigation of the violence that marked the partition of British India in 1947, this book analyses questions of history and mem- ory, the nationalisation of populations and their pasts, and the ways in which violent events are remembered (or forgotten) in order to en- sure the unity of the collective subject – community or nation. Stressing the continuous entanglement of ‘event’ and ‘interpretation’, the author emphasises both the enormity of the violence of 1947 and its shifting meanings and contours. The book provides a sustained critique of the procedures of history-writing and nationalist myth-making on the ques- tion of violence, and examines how local forms of sociality are consti- tuted and reconstituted by the experience and representation of violent events. It concludes with a comment on the different kinds of political community that may still be imagined even in the wake of Partition and events like it. GYANENDRA PANDEY is Professor of Anthropology and History at Johns Hopkins University. He was a founder member of the Subaltern Studies group and is the author of many publications including The Con- struction of Communalism in Colonial North India (1990) and, as editor, Hindus and Others: the Question of Identity in India Today (1993). This page intentionally left blank Contemporary South Asia 7 Editorial board Jan Breman, G.P. Hawthorn, Ayesha Jalal, Patricia Jeffery, Atul Kohli Contemporary South Asia has been established to publish books on the politics, society and culture of South Asia since 1947. -

Son of the Desert

Dedicated to Mohtarma Benazir Bhutto Shaheed without words to express anything. The Author SONiDESERT A biography of Quaid·a·Awam SHAHEED ZULFIKAR ALI H By DR. HABIBULLAH SIDDIQUI Copyright (C) 2010 by nAfllST Printed and bound in Pakistan by publication unit of nAfllST Shaheed Zulfikar Ali Bhutto/Shaheed Benazir Bhutto Archives. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. First Edition: April 2010 Title Design: Khuda Bux Abro Price Rs. 650/· Published by: Shaheed Zulfikar Ali Bhutto/ Shaheed Benazir Bhutto Archives 4.i. Aoor, Sheikh Sultan Trust, Building No.2, Beaumont Road, Karachi. Phone: 021-35218095-96 Fax: 021-99206251 Printed at: The Time Press {Pvt.) Ltd. Karachi-Pakistan. CQNTENTS Foreword 1 Chapter: 01. On the Sands of Time 4 02. The Root.s 13 03. The Political Heritage-I: General Perspective 27 04. The Political Heritage-II: Sindh-Bhutto legacy 34 05. A revolutionary in the making 47 06. The Life of Politics: Insight and Vision· 65 07. Fall out with the Field Marshal and founding of Pakistan People's Party 108 08. The state dismembered: Who is to blame 118 09. The Revolutionary in the saddle: New Pakistan and the People's Government 148 10. Flash point.s and the fallout 180 11. Coup d'etat: tribulation and steadfasmess 197 12. Inside Death Cell and out to gallows 220 13. Home they brought the warrior dead 229 14. -

Revista Dilemas Contemporáneos: Educación, Política Y Valores. Http

1 Revista Dilemas Contemporáneos: Educación, Política y Valores. http://www.dilemascontemporaneoseducacionpoliticayvalores.com/ Año: VII Número: Edición Especial Artículo no.:97 Período: Octubre, 2019. TÍTULO: El papel de los Santuarios en el Movimiento por la Libertad de la India y en Pakistán: una perspectiva histórica. AUTORES: 1. Dr. Abdul Qadir Mushtaq. 2. Ph.D. stud. Fariha Sohil. RESUMEN: Tres comunidades: hindúes, musulmanes y el gobierno británico, se enfrentaron durante el movimiento de libertad indio. Esta batalla ideológica y realpolítica se libró en todo el subcontinente indio. Es irónico que la comunidad musulmana se dividiera en dos escuelas de pensamiento como su respuesta al nacionalismo. Fue esta vez cuando el liderazgo religioso y político estaban luchando por la protección de los derechos de la comunidad musulmana. Estos derechos eran tanto políticos como religiosos. Esta contribución de Sajjada Nashins se jugó en tres niveles: su atractivo personal, su apoyo institucional sufí y su compromiso con el principal partido político musulmán; es decir, toda la Liga Musulmana de la India. El trabajo analiza los servicios de los Sajjada Nashines de los santuarios, para resaltar su contribución a la comunidad musulmana y la creación de Pakistán. El estudio es exploratorio, descriptivo y analítico. PALABRAS CLAVES: Movimiento de libertad, comunidades, batalla, nacionalismo indio, personalidades religiosas. 2 TITLE: Role of Shrines in Indian Freedom Movement and Pakistan: A historical perspective. AUTHORS: 1. Ph.D. Abdul Qadir Mushtaq. 2. Ph.D. stud. Fariha Sohil. ABSTRACT: Three communities— the Hindus, Muslims and the British Government— were confronted with each other during the Indian freedom movement. This ideological as well as realpolitik battle was fought in whole Indian subcontinent. -

Maharaja Judgement

RSA Nos.2006, 1418 & 2176 of 2018 (O&M) 1 IN THE HIGH COURT OF PUNJAB AND HARYANA AT CHANDIGARH 1. RSA No.2006 of 2018 (O&M) Date of Decision:01.06.2020 Rajkumari Amrit Kaur ......Appellant(s) Vs Maharani Deepinder Kaur and others ....Respondent(s) 2. RSA No.1418 of 2018 (O&M) Maharani Deepinder Kaur and others ......Appellant(s) Vs Rajkumari Amrit Kaur and others ....Respondent(s) 3. RSA No.2176 of 2018 (O&M) Bharat Inder Singh (since deceased) though his LR Kanwar Amarinder Singh Brar ......Appellant(s) Vs Maharwal Khewaji Trust through its Boards of Trustees and others ....Respondent(s) CORAM: HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE RAJ MOHAN SINGH Present: Mr. Manjit Singh Khaira, Sr. Advocate with Mr. Balbir Singh Sewak, Advocate, Mr. Dharminder Singh Randhawa, Advocate Mr. Ripudaman Singh Sidhu, Advocate, and Mr. Gagandeep Singh Mann, Special Attorney Holder for the appellant in RSA No.2006 of 2018 for respondent No.1 in RSA No.1418 of 2018 and for respondent No.6 in RSA No.2176 of 2018. Mr. Ashok Aggarwal, Sr. Advocate with Mr. Mukul Aggarwal, Advocate Mr. N.S. Wahniwal, Advocate for the appellants in RSA No.1418 of 2018 for respondents No.1, 2, 3(1), 3(2), 3(5) & 3(8) in RSA No.2006 of 2018; for respondents No.1(A), 1(B), 1(E), 1(F), 2 and 3 in 1 of 547 ::: Downloaded on - 11-06-2020 14:06:01 ::: RSA Nos.2006, 1418 & 2176 of 2018 (O&M) 2 RSA No.2176 of 2018. Mr. Vivek Bhandari, Advocate for the appellant in RSA No.2176 of 2018 for respondent No.5(i) in RSA No.2006 of 2018 and for respondent No.3(i) in RSA No.1418 of 2018.