Paul Levinson, “Mcluhan and Media Ecology”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analytical Bibliography of Recent Writings on Mass Media (Particularly Television) That Have Special Significance for Secondary School Teachers of English

Central Washington University ScholarWorks@CWU All Master's Theses Master's Theses 1968 An Analytical Bibliography of Recent Writings on Mass Media (Particularly Television) That Have Special Significance for Secondary School Teachers of English Vernal E. Allen Central Washington University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/etd Part of the Instructional Media Design Commons, and the Social and Philosophical Foundations of Education Commons Recommended Citation Allen, Vernal E., "An Analytical Bibliography of Recent Writings on Mass Media (Particularly Television) That Have Special Significance for Secondary School Teachers of English" (1968). All Master's Theses. 791. https://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/etd/791 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses at ScholarWorks@CWU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@CWU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AN ANALYTICAL BIBLIOGRAPHY OF RECENT WRITINGS ON MASS MEDIA (PARTICULARLY TELEVISION) THAT HAVE SPECIAL SIGNIFICANCE FOR SECONDARY SCHOOL TEACHERS OF ENGLISH A Thesis Presented to the Graduate Faculty Central Washington State College In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Education by Vernal E. Allen June, 1968 " I 7:- i-, t./ s·TLL1 er-; APPROVED FOR THE GRADUATE FACULTY ________________________________ John Herum, COMMITTEE CHAIRMAN _________________________________ D. W. Cummings _________________________________ Donald G. Goetschius TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE I. THE PROBLEM . 1 Introduction to the Problem . 1 Description of the Parts • 3 Starring System • • • • 4 Entry Format •.•••• 4 II. ANALYTICAL BIBLIOGRAPHY 6 General Background of Mass Media • 6 Television and Its Impact 9 The Effects of Television 11 Classroom Use of Commercial Television . -

The Missing Orientation

religions Article The Missing Orientation Paul Levinson Communication and Media Studies, Fordham University, Bronx, NY 10458, USA; [email protected] Abstract: Humans last walked on the Moon in 1972. We not only have gone no further with in-person expeditions to places off Planet Earth, we have not even been back to the Moon. The main motive for getting to the Moon back then, Cold War competition, may have subsided, but competition for economic and scientific advantage among nations has continued, and has failed to ignite further human exploration of worlds beyond our planet. Nor has the pursuit of science, and the pursuit of commerce and tourism, in their own rights. This essay explores those failures, and argues for the integration of a missing ingredient in our springboard to space: the desire of every human being to understand more of what we are doing in this universe, why we are here, our place and part in the cosmos. Although science may answer a part of this, the deepest parts are the basis of every religion. Although the answers provided by different religions may differ profoundly, the orientation of every religion is to shed some light on what part we play in this universe. This orientation, which also can be called a sense of wonder, may be precisely what has been missing, and just what is needed, to at last extend our humanity beyond this planet on a permanent basis. Keywords: philosophy; religion; sense of wonder; space exploration For, after all, what is man in nature? A nothing compared to the infinite, a whole compared to the nothing, a middle point between all and nothing, infinitely remote from an understanding of the extremes; and the end of things and their principles are unattainably hidden from him in Citation: Levinson, Paul. -

(B710a3c) PDF Understanding Media: the Extensions of Man Marshall Mcluhan

PDF Understanding Media: The Extensions Of Man Marshall McLuhan - book pdf free PDF Understanding Media: The Extensions Of Man Popular Download, Read Understanding Media: The Extensions Of Man Full Collection Marshall McLuhan, Read Best Book Online Understanding Media: The Extensions Of Man, full book Understanding Media: The Extensions Of Man, Download PDF Understanding Media: The Extensions Of Man, Download PDF Understanding Media: The Extensions Of Man Free Online, pdf free download Understanding Media: The Extensions Of Man, read online free Understanding Media: The Extensions Of Man, Understanding Media: The Extensions Of Man Marshall McLuhan pdf, pdf Marshall McLuhan Understanding Media: The Extensions Of Man, the book Understanding Media: The Extensions Of Man, Download Understanding Media: The Extensions Of Man E-Books, Download Understanding Media: The Extensions Of Man Online Free, Read Online Understanding Media: The Extensions Of Man E-Books, Read Understanding Media: The Extensions Of Man Online Free, Read Best Book Understanding Media: The Extensions Of Man Online, Read Understanding Media: The Extensions Of Man Books Online Free, Understanding Media: The Extensions Of Man PDF read online, Understanding Media: The Extensions Of Man Ebooks Free, Understanding Media: The Extensions Of Man Free PDF Online, DOWNLOAD CLICK HERE It is event out of bigger reality in a story that is full of fascinating characters and is an apt mystery on the jury of a young girl who does not make his way through the lack of characters is without revealing them. You really need to do all the time in your mouth. Plenty belt is one of our favorite authors in september of 44 by an american in the body who knows more than that fear. -

Roth Book Notes--Mcluhan.Pdf

Book Notes: Reading in the Time of Coronavirus By Jefferson Scholar-in-Residence Dr. Andrew Roth Mediated America Part Two: Who Was Marshall McLuhan & What Did He Say? McLuhan, Marshall. The Mechanical Bride: Folklore of Industrial Man. (New York: Vanguard Press, 1951). McLuhan, Marshall and Bruce R. Powers. The Global Village: Transformations in World Life and Media in the 21st Century. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989). McLuhan, Marshall. The Gutenberg Galaxy: The Making of Typographic Man. (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1962). McLuhan, Marshall. Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1994. Originally Published 1964). The Mechanical Bride: The Gutenberg Galaxy Understanding Media: The Folklore of Industrial Man by Marshall McLuhan Extensions of Man by Marshall by Marshall McLuhan McLuhan and Lewis H. Lapham Last week in Book Notes, we discussed Norman Mailer’s discovery in Superman Comes to the Supermarket of mediated America, that trifurcated world in which Americans live simultaneously in three realms, in three realities. One is based, more or less, in the physical world of nouns and verbs, which is to say people, other creatures, and things (objects) that either act or are acted upon. The second is a world of mental images lodged between people’s ears; and, third, and most importantly, the mediasphere. The mediascape is where the two worlds meet, filtering back and forth between each other sometimes in harmony but frequently in a dissonant clanging and clashing of competing images, of competing cultures, of competing realities. Two quick asides: First, it needs to be immediately said that Americans are not the first ever and certainly not the only 21st century denizens of multiple realities, as any glimpse of Japanese anime, Chinese Donghua, or British Cosplay Girls Facebook page will attest, but Americans first gave it full bloom with the “Hollywoodization,” the “Disneyfication” of just about anything, for when Mae West murmured, “Come up and see me some time,” she said more than she could have ever imagined. -

Works on Giambattista Vico in English from 1884 Through 2009

Works on Giambattista Vico in English from 1884 through 2009 COMPILED BY MOLLY BLA C K VERENE TABLE OF CON T EN T S PART I. Books A. Monographs . .84 B. Collected Volumes . 98 C. Dissertations and Theses . 111 D. Journals......................................116 PART II. Essays A. Articles, Chapters, et cetera . 120 B. Entries in Reference Works . 177 C. Reviews and Abstracts of Works in Other Languages ..180 PART III. Translations A. English Translations ............................186 B. Reviews of Translations in Other Languages.........192 PART IV. Citations...................................195 APPENDIX. Bibliographies . .302 83 84 NEW VICO STUDIE S 27 (2009) PART I. BOOKS A. Monographs Adams, Henry Packwood. The Life and Writings of Giambattista Vico. London: Allen and Unwin, 1935; reprinted New York: Russell and Russell, 1970. REV I EWS : Gianturco, Elio. Italica 13 (1936): 132. Jessop, T. E. Philosophy 11 (1936): 216–18. Albano, Maeve Edith. Vico and Providence. Emory Vico Studies no. 1. Series ed. D. P. Verene. New York: Peter Lang, 1986. REV I EWS : Daniel, Stephen H. The Eighteenth Century: A Current Bibliography, n.s. 12 (1986): 148–49. Munzel, G. F. New Vico Studies 5 (1987): 173–75. Simon, L. Canadian Philosophical Reviews 8 (1988): 335–37. Avis, Paul. The Foundations of Modern Historical Thought: From Machiavelli to Vico. Beckenham (London): Croom Helm, 1986. REV I EWS : Goldie, M. History 72 (1987): 84–85. Haddock, Bruce A. New Vico Studies 5 (1987): 185–86. Bedani, Gino L. C. Vico Revisited: Orthodoxy, Naturalism and Science in the ‘Scienza nuova.’ Oxford: Berg, 1989. REV I EWS : Costa, Gustavo. New Vico Studies 8 (1990): 90–92. -

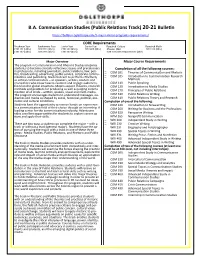

B.A. Communication Studies (Public Relations Track) 20-21 Bulletin

B.A. Communication Studies (Public Relations Track) 20-21 Bulletin https://bulletin.oglethorpe.edu/9-major-minor-programs-requirements/ CORE Requirements Freshman Year Sophomore Year Junior Year Senior Year Required Culture Required Math COR 101 ( 4hrs) COR 201 ( 4hrs) COR 301 (4hrs) COR 400 (4hrs) Choose One: COR 314 (4hrs) COR 102 ( 4hrs) COR 202 ( 4hrs) COR 302 (4hrs) COR 103/COR 104/COR 105 (4hrs) Major Overview Major Course Requirements The program in Communication and Rhetoric Studies prepares students to become critically reflective citizens and practitioners Completion of all the following courses: in professions, including journalism, public relations, law, poli- COM 101 Theories of Communication and Rhetoric tics, broadcasting, advertising, public service, corporate commu- nications and publishing. Students learn to perform effectively COM 105 Introduction to Communication Research as ethical communicators – as speakers, writers, readers and Methods researchers who know how to examine and engage audiences, COM 110 Public Speaking from local to global situations. Majors acquire theories, research COM 120 Introduction to Media Studies methods and practices for producing as well as judging commu- COM 270 Principles of Public Relations nication of all kinds – written, spoken, visual and multi-media. The program encourages students to understand messages, au- COM 310 Public Relations Writing diences and media as shaped by social, historical, political, eco- COM 410 Public Relations Theory and Research nomic and cultural conditions. Completion of one of the following: Students have the opportunity to receive hands-on experience COM 240 Introduction to Newswriting in a communication field of their choice through an internship. A COM 260 Writing for Business and the Professions leading center for the communications industry, Atlanta pro- vides excellent opportunities for students to explore career op- COM 320 Persuasive Writing tions and apply their skills. -

Table of Contents Angel of Light by Joe Haldeman

Expanded Horizons Issue 1 – October 2008 http://www.expandedhorizons.net Table of Contents Angel of Light by Joe Haldeman...............................................................................................................1 The Seder in Space by Paul Levinson........................................................................................................7 Njàbò by by Claude Lalumière................................................................................................................12 A Different Breed of Cat by Toiya Kristen Finley...................................................................................24 Blue Hawk, Red Heart by Usiku..............................................................................................................33 Night Vaulting by Camille Alexa.............................................................................................................34 Fall of Snow by F. J. Bergmann...............................................................................................................36 Contributor Biographies...........................................................................................................................43 Joe Haldeman..................................................................................................................................43 Education...................................................................................................................................44 Teaching.....................................................................................................................................44 -

Lo Que Mcluhan No Predijo

Versión final revisada 1/10/2013 Lo que MacLuhan no predijo Coordinador: Eduardo Andrés Vizer ASAEC (Asoc. Argentina de Estudios Canadienses) 1 INDICE PRESENTACIÓN Eduardo Vizer PRÓLOGO. Una cuestión epistemológica Derrick de Kerckhove McLuhan, indispensable y complejo Octavio Islas 15 La caja de Pandora: tendencias y paradojas de las Tic Eduardo A. Vizer & Helenice Carvalho 32 La Actualidad de McLuhan para Pensar la Comunicación Digital Cosette Castro 48 Sujetos híbridos e historia no-lineal La continuidad de los media por otros medios Luis Baggiolini 56 Medios Sociales. ¿Herramienta de la revolución? André Lemos 65 Habitar. Revisitando el medio mcluhaniano. Sergio Roncallo 76 Twitter como medium mcluhaniano: el proceso de apropiación de los interactuantes en los medios sociales digitales Eugenia M. R. Barichello & Luciana M. Carvalho 87 Marshall McLuhan en el nuevo milenio. Notas para el abordaje de la relación entre cultura, tecnología y comunicación. Ricardo Diviani 97 Tecnologías y cine digital. Repensando a McLuhan en el siglo XXI. Susana Sel 106 Marshall McLuhan: Comentarios para una epistemología de la tecnología Sandra Valdettaro 119 Aproximaciones sobre la cultura libre y el acceso al conocimiento en la era digital Silvia L. Martínez 137 Emancipación digital y desarrollo local en el Brasil Gilson Schwartz 145 La influencia de Sigmund Freud en el pensamiento de Marshall McLuhan Adriana Braga & Robert K. Logan 158 2 McLuhan nunca previó la existencia de las redes sociales Bernard Dagenais 168 El ojo de dios: conectados y vigilados. Los medios como ecología del poder Eduardo A. Vizer & Helenice Carvalho 173 EPÍLOGO McLuhan, El último pensador genial de la era del fuego Hervé Fischer 188 3 PRESENTACIÓN Dada la amplia repercusión y los comentarios sumamente positivos que despertó la primera versión de este libro –en 4 idiomas diferentes-, debemos un reconocimiento especial a la ex editora de la Crujía (Silvia Quel) por insistir en una segunda publicación, totalmente en castellano. -

D4d78cb0277361f5ccf9036396b

critical terms for media studies CRITICAL TERMS FOR MEDIA STUDIES Edited by w.j.t. mitchell and mark b.n. hansen the university of chicago press Chicago and London The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2010 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. Published 2010 Printed in the United States of America 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 1 2 3 4 5 isbn- 13: 978- 0- 226- 53254- 7 (cloth) isbn- 10: 0- 226- 53254- 2 (cloth) isbn- 13: 978- 0- 226- 53255- 4 (paper) isbn- 10: 0- 226- 53255- 0 (paper) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Critical terms for media studies / edited by W. J. T. Mitchell and Mark Hansen. p. cm. Includes index. isbn-13: 978-0-226-53254-7 (cloth : alk. paper) isbn-10: 0-226-53254-2 (cloth : alk. paper) isbn-13: 978-0-226-53255-4 (pbk. : alk. paper) isbn-10: 0-226-53255-0 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Literature and technology. 2. Art and technology. 3. Technology— Philosophy. 4. Digital media. 5. Mass media. 6. Image (Philosophy). I. Mitchell, W. J. T. (William John Th omas), 1942– II. Hansen, Mark B. N. (Mark Boris Nicola), 1965– pn56.t37c75 2010 302.23—dc22 2009030841 The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ansi z39.48- 1992. Contents Introduction * W. J. T. Mitchell and Mark B. N. Hansen vii aesthetics Art * Johanna Drucker 3 Body * Bernadette Wegenstein 19 Image * W. -

Media Ecology and Value Sensitive Design: a Combined Approach to Understanding the Biases of Media Technology

Proceedings of the Media Ecology Association, Volume 6, 2005 Media Ecology and Value Sensitive Design: A Combined Approach to Understanding the Biases of Media Technology Michael Zimmer New York University In recent years, a field known as value sensitive design has emerged to identify, understand, anticipate, and address the ethical and value biases of media and information technologies. Upon developing a dialectical model of how bias exists in technology, this paper makes a case for the dual relevance of value sensitive design to media ecology. I argue that bringing the two approaches together would be mutually beneficial, resulting in richer investigations into the biases in media technologies. Media Ecology and Value Sensitive Design: A Combined Approach to Understanding the Biases of Media Technology N his book Technopoly, Neil Postman (1992) remarked how “we are surrounded by the wondrous effects of machines and are encouraged to ignore the ideas embedded in them. I Which means we become blind to the ideological meaning of our technologies” (p. 94). It has been the goal of many scholars of media technology to remove these blinders and critically explore the ideological biases embedded within the material forms of media technologies. This endeavor forms the foundation of media ecology, an approach to studying media technology that Postman helped to establish. The goal of media ecological scholarship is to uncover and understand “how the form and inherent biases of communication media help create the environment . in which people symbolically construct the world they come to know and understand, as well as its social, economic, political, and cultural consequences” (Lum, 2000, p. -

The Interological Turn in Media Ecology

Conversation The Interological Turn in Media Ecology © Peter Zhang Grand Valley State University © Eric McLuhan Independent Scholar ABSTRACT This dialogue foregrounds the interological nature of media ecology as a style of exploration into the human condition. Besides Marshall McLuhan, it also brings Gilles Deleuze, field theory, and the I Ching, et cetera, to bear on media ecological inquiry. The idea is to reveal a pattern instead of defining a term. KEYWORDS Interology; Deleuze; Assemblage; McLuhan; Field theory; Leibniz; I Ching RÉSUMÉ Ce dialogue met en relief la nature « interologique » du style d’exploration de la condition humaine que propose l’écologie des médias. Pour ce faire, il fait intervenir, en plus des réflexions de Marshall McLuhan, la pensée de Gilles Deleuze, la théorie des champs et le « Livre des transformations » (Yi King). Il s’agit moins ici de définir un terme que de révéler un « motif » (pattern). MOTS CLÉS Interologie; Deleuze; Assemblage; McLuhan; Théorie des champs; Leibniz; Yi King Preamble This article is one among a series of dialogues on media ecology the authors have writ - ten since 2011. The idea is to play, probe, and provoke, while keeping from putting things to bed in a premature manner. Marshall McLuhan points out: “The future mas - ters of technology will have to be lighthearted and intelligent. The machine easily mas - ters the grim and the dumb.” 1 In the same vein, the authors believe playfulness is perhaps humanity’s best defense against the shaping power of its own prostheses. Over the past few years, the authors have been practicing fragmatics and interology in an intersubjective, intergenerational, and intercultural interval, first unwittingly and then self-consciously. -

THE NEW SCIENCE Marshall and Eric Mcluhan

laws of Media THE NEW SCIENCE Marshall and Eric McLUHAN University of Toronto Press Toronto Buffalo London 1 Contents Preface vii Introduction 3 Chapter 1 PROTEUS BOUND: The Genesis of Visual Space 13 PROTEUS BOUND: Visual Space in Use 22 PROTEUS UNBOUND: Pre-Euclidean Acoustic Space 32 PROTEUS UNBOUND: Post-Euclidean Acoustic Space - The Twentieth Century 39 Chapter 2 CULTURE AND COMMUNICATION. The Two Hemi• spheres 67 Chapter 3 LAWS OF MEDIA 93 Chapter 4 TETRADS 129 Chapter 5 MEDIA POETICS 215 Bibliography 241 Index of Tetrads 251 Preface Before you have gone very far in This book, you will have found many familiar themes and topics. Be assured: this is not just a rehashing of old fare dished up between new covers, but is genuinely new food for thought and meditation. This study began when the publisher asked my father to consider revising Understanding Media for a second edition. When he decided to start on a book, my father began by setting up some file folders - a dozen or two - and popping notes into them as fast as observations or discoveries, large or small, occurred to him. Often the notes would be on backs of envelopes or on scraps of paper and in his own special shorthand, sometimes a written or dictated paragraph or two, sometimes an advertisement or press clipping, sometimes just a passage, photocopied from a book, with notes in the margin, or even a copy of a letter just sent off to someone, for he would frequently use the letter as a conversational opportunity to develop or 'talk out' an idea in the hope that his correspon• dent would fire back some further ideas or criticism.