D4d78cb0277361f5ccf9036396b

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ORANGE COUNTY CAUFORNIA Continued on Page 53

KENNEDY KLUES Research Bulletin VOLUME II NUMBER 2 & 3 · November 1976 & February 1977 Published by:. Mrs • Betty L. Pennington 6059 Emery Street Riverside, California 92509 i . SUBSCRIPTION RATE: $6. oo per year (4 issues) Yearly Index Inc~uded $1. 75 Sample copy or back issues. All subscriptions begin with current issue. · $7. 50 per year (4 issues) outside Continental · · United States . Published: · August - November - Febr:UarY . - May .· QUERIES: FREE to subscribers, no restrictions as· ·to length or number. Non subscribers may send queries at the rate of 10¢ pe~)ine, .. excluding name and address. EDITORIAL POLICY: -The E.ditor does· not assume.. a~y responsibility ~or error .. of fact bR opinion expressed by the. contributors. It is our desire . and intent to publish only reliable genealogical sour~e material which relate to the name of KENNEDY, including var.iants! KENEDY, KENNADY I KENNEDAY·, KENNADAY I CANADA, .CANADAY' · CANADY,· CANNADA and any other variants of the surname. WHEN YOU MOVE: Let me know your new address as soon as possibie. Due. to high postal rates, THIS IS A MUST I KENNEDY KLyES returned to me, will not be forwarded until a 50¢ service charge has been paid, . coi~ or stamps. BOOK REVIEWS: Any biographical, genealogical or historical book or quarterly (need not be KENNEDY material) DONATED to KENNEDY KLUES will be reviewed in the surname· bulletins·, FISHER FACTS, KE NNEDY KLUES and SMITH SAGAS • . Such donations should be marked SAMfLE REVIEW COPY. This is a form of free 'advertising for the authors/ compilers of such ' publications~ . CONTRIBUTIONS:· Anyone who has material on any KE NNEDY anywhere, anytime, is invited to contribute the material to our putilication. -

Claude Bernard

DOI: 10.1590/0004-282X20130239 HISTORICAL NOTES Claude Bernard: bicentenary of birth and his main contributions to neurology Claude Bernard: bicentenário do nascimento e suas principais contribuições à neurologia Marleide da Mota Gomes1, Eliasz Engelhardt2 ABSTRACT Claude Bernard (1813-1878) followed two main research paths: the chemical and physiological study of digestion and liver function, along with experimental section of nerves and studies on sympathetic nerves. Curare studies were, for example, of longstanding interest. His profound mental creativity and hand skillfulness, besides methodology quality, directed his experiments and findings, mainly at the Collège de France. His broader and epistemological concerns were carried out at the Sorbonne and later at the Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle. His insight gave clues to define the “ milieu intérieur”, later known as “homeostasis”, and grasp the brain complexity. Bernard followed and surpassed his master François Magendie who also fought against dogmas and laid the foundations of experimental medicine, and its main heinous tool – vivisection. Bernard created the methodological bases of experimental medicine, and collected honors as a renowned researcher. Keywords: Claude Bernard, sympathetic nerves, homeosthasis, epistemology, history of neurosciences. RESUMO Em suas pesquisas, Claude Bernard (1813-1878) seguiu dois caminhos principais: o estudo fisiológico e químico da digestão e da função hepática; a seção experimental de nervos e os estudos sobre nervos simpáticos. Estudos sobre curare, por exemplo, foram de interesse duradouro. Suas profundas criatividade mental e habilidade manual, além da qualidade metodológica, conduziram às suas experiências e descobertas, principalmente no Collège de France. Seus interesses sobre temas epistemológicos mais amplos foram conduzidos na Sorbonne e, posteriormente, no Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle. -

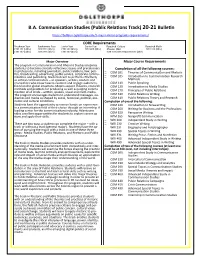

B.A. Communication Studies (Public Relations Track) 20-21 Bulletin

B.A. Communication Studies (Public Relations Track) 20-21 Bulletin https://bulletin.oglethorpe.edu/9-major-minor-programs-requirements/ CORE Requirements Freshman Year Sophomore Year Junior Year Senior Year Required Culture Required Math COR 101 ( 4hrs) COR 201 ( 4hrs) COR 301 (4hrs) COR 400 (4hrs) Choose One: COR 314 (4hrs) COR 102 ( 4hrs) COR 202 ( 4hrs) COR 302 (4hrs) COR 103/COR 104/COR 105 (4hrs) Major Overview Major Course Requirements The program in Communication and Rhetoric Studies prepares students to become critically reflective citizens and practitioners Completion of all the following courses: in professions, including journalism, public relations, law, poli- COM 101 Theories of Communication and Rhetoric tics, broadcasting, advertising, public service, corporate commu- nications and publishing. Students learn to perform effectively COM 105 Introduction to Communication Research as ethical communicators – as speakers, writers, readers and Methods researchers who know how to examine and engage audiences, COM 110 Public Speaking from local to global situations. Majors acquire theories, research COM 120 Introduction to Media Studies methods and practices for producing as well as judging commu- COM 270 Principles of Public Relations nication of all kinds – written, spoken, visual and multi-media. The program encourages students to understand messages, au- COM 310 Public Relations Writing diences and media as shaped by social, historical, political, eco- COM 410 Public Relations Theory and Research nomic and cultural conditions. Completion of one of the following: Students have the opportunity to receive hands-on experience COM 240 Introduction to Newswriting in a communication field of their choice through an internship. A COM 260 Writing for Business and the Professions leading center for the communications industry, Atlanta pro- vides excellent opportunities for students to explore career op- COM 320 Persuasive Writing tions and apply their skills. -

Independent Agencies, Commissions, Boards

INDEPENDENT AGENCIES, COMMISSIONS, BOARDS ADVISORY COUNCIL ON HISTORIC PRESERVATION 1100 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW., Suite 803, 20004 phone (202) 606–8503, http://www.achp.gov [Created by Public Law 89–665, as amended] Executive Director.—John M. Fowler. Chairman.—Milford Wayne Donaldson, Sacramento, California. Vice Chairman.—Vacant. Directors for: Office of Administration.—Ralston Cox. Office of Communications, Education, and Outreach.—Susan A. Glimcher. Office of Federal Agency Programs.—Reid J. Nelson. Office of Native American Affairs.—Valerie Hauser. Office of Preservation Initiatives.—Ronald D. Anzalone. Expert Members: Jack Williams, Seattle, Washington. Ann Alexander Pritzlaff, Denver, Colorado. Julia A. King, St. Leonard, Maryland. Horace H. Foxall, Jr., Seattle, Washington. Citizen Members: Bradford J. White, Evanston, Illinois. John A. Garcia, Albuquerque, New Mexico. Mark A. Sadd, Esq., Charleston, West Virginia. Native American Member.—John L. Berrey, Quapaw, Oklahoma. Governor.—Vacant. Mayor.—Hon. Michael B. Coleman, Columbus, Ohio. Architect of the Capitol.—Stephen T. Ayers, AIA. Secretary, Department of: Agriculture.—Hon. Thomas J. Vilsack. Commerce.—Hon. John E. Bryson. Defense.—Dr. Robert Gates. Education.—Hon. Arne Duncan. Housing and Urban Development.—Hon. Shaun Donovan. Interior.—Hon. Kenneth L. Salazar. Transportation.—Hon. Ray LaHood. Veterans’ Affairs.—Hon. Eric K. Shinseki. Administrator of General Services Administration.—Martha Johnson. National Conference of State Historic Preservation Officer.—Ruth Pierpont, President, Water- ford, New York. National Trust for Historic Preservation.—Carolyn Brody, Chairman, Washington, DC. AMERICAN BATTLE MONUMENTS COMMISSION Courthouse Plaza II, Suite 500, 2300 Clarendon Boulevard, Arlington, VA 22201–3367 phone (703) 696–6902 [Created by Public Law 105–225] Chairman.—Merrill A. McPeak appointed as of 6/3/11. -

Features of Media Multitasking Experiences

WP2 MEDIA MULTITASKING D2.3.3.6 FEATURES OF MEDIA MULTITASKING EXPERIENCES Media Multitasking D2.3.3.6 Features of media multitasking experience s Authors: Maria Viitanen, Stina Westman, Teemu Kinnunen, Pirkko Oittinen Confidentiality: Consortium Date and status: August 31st , 2012, version 0.1 This work was supported by TEKES as part of the next Media programme of TIVIT (Finnish Strategic Centre for Science, Technology and Innovation in the field of ICT) Next Media - a Tivit Programme Phase 3 (1.1.–31.12.2012) Version history: Version Date State Author(s) OR Remarks (draft/ /update/ final) Editor/Contributors 0.1 31 st August MV, SW, TK, PO Review version {Participants = all research organisations and companies involved in the making of the deliverable} Participants Name Organisation Maria Viitanen Aalto University Researchers Stina Westman Department of Media Teemu Kinnunen Technology Pirkko Oittinen next Media www.nextmedia.fi www.tivit.fi WP2 MEDIA MULTITASKING D2.3.3.6 FEATURES OF MEDIA MULTITASKING EXPERIENCES 1 (40) Next Media - a Tivit Programme Phase 3 (1.1.–31.12.2012) Executive Summary Media multitasking is gaining attention as a phenomenon affecting media consumption especially among younger generations. From both social and technical viewpoints it is an important shift in media use, affecting and providing opportunities for content providers, system designers and advertisers alike. Media multitasking may be divided into media multitasking which refers to using several media together and multitasking with media, which consists of combining non- media activities with media use. In this deliverable we review research on multitasking from various disciplines: cognitive psychology, education, human-computer interaction, information science, marketing, media and communication studies, and organizational studies. -

Information Technology and the Topologies of Transmission: a Research Area for Historical Simulation

Miguel, Amblard, Barceló & Madella (eds.) Advances in Computational Social Science and Social Simulation Barcelona: Autònoma University of Barcelona, 2014, DDD repository <http://ddd.uab.cat/record/125597> Information Technology and the Topologies of Transmission: a Research Area for Historical Simulation Nicholas Mark Gotts Independent researcher Email: [email protected] sensory qualities, and by how often similar objects have been Abstract—This paper surveys possibilities for applying the seen. They can be acquired in three ways: by being found, methods of agent-based simulation to the study of historical perhaps with subsequent modification, traded (within or out- transitions in communication technology. with the social group), or stolen; and all these methods could be included in a fairly simple model. Possession of such ob- INTRODUCTION jects could increase the probability that other individuals will ISTORY, in one sense, begins with the invention and cooperate with the owner – but also the possibility that they Hadoption of a particular information technology: writ- will attack the owner to acquire the object. Outcomes of such ing. Initially appearing in Mesopotamia some 5,000 years models (the distribution of prestige objects, peaceful or vio- ago, it has spread (mainly by diffusion, but with some proba- lent transfers of possession, survival of their possessors, ef- ble cases of independent invention) to cover effectively the fects on trade between groups) could be compared with ar- whole world. Other key communication technologies -

Networks of Modernity: Germany in the Age of the Telegraph, 1830–1880

OUP CORRECTED AUTOPAGE PROOFS – FINAL, 24/3/2021, SPi STUDIES IN GERMAN HISTORY Series Editors Neil Gregor (Southampton) Len Scales (Durham) Editorial Board Simon MacLean (St Andrews) Frank Rexroth (Göttingen) Ulinka Rublack (Cambridge) Joel Harrington (Vanderbilt) Yair Mintzker (Princeton) Svenja Goltermann (Zürich) Maiken Umbach (Nottingham) Paul Betts (Oxford) OUP CORRECTED AUTOPAGE PROOFS – FINAL, 24/3/2021, SPi OUP CORRECTED AUTOPAGE PROOFS – FINAL, 24/3/2021, SPi Networks of Modernity Germany in the Age of the Telegraph, 1830–1880 JEAN-MICHEL JOHNSTON 1 OUP CORRECTED AUTOPAGE PROOFS – FINAL, 24/3/2021, SPi 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries © Jean-Michel Johnston 2021 The moral rights of the author have been asserted First Edition published in 2021 Impression: 1 Some rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, for commercial purposes, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. This is an open access publication, available online and distributed under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution – Non Commercial – No Derivatives 4.0 International licence (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), a copy of which is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. -

Media Studies and Production Diploam Program Guide

Media Studies and Production Diploma - 31 credits Program Area: Media Studies (Fall 2019) ***REMEMBER TO REGISTER EARLY*** Program Description Required Courses This program is designed to Course Course Title Credits Term prepare the graduate for a wide MCOM 1400* Intro to Mass 3 Communication variety of positions in media MCOM 1420* Digital Video 3 production. Graduates are trained Production for jobs ranging from highly visible MCOM 1422* Audio for the Media 3 on-the-air assignments to positions ENGL 1106* College Composition I 3 on production or news teams. MCOM 1424 Digital Video Editing 3 Graduates can also gain skills MCOM 1426 Project/Production 3 needed for careers in multimedia, Management DVD authoring, film style MCOM 1428* Interactive Media 3 production, and media project & Production MCOM 1795* Portfolio Production 1 production management. Lake MCOM 1797* Media Studies 3 Superior College media studies Internship students receive valuable hands- Electives 6 on experience in LSC’s own audio (refer to Table 1) and video studios, as well as Total credits 31 through internships and *Requires a prerequisite or instructor’s consent experiences at local broadcast stations and media agencies. Program Outcomes Upon graduation, students will be able to: • Shoot and edit single camera media productions using both analog and digital equipment. • Participate in cooperative media production teams. • Voice, record, edit, and produce audio projects, promotions, and commercials using both analog and digital equipment. • Use terms and techniques common to media production and process. Pre-program Requirements Successful entry into this program requires a specific level of skill in the areas of English, mathematics, and reading. -

Journalism, Advertising, and Media Studies (JAMS)

Journalism, Advertising, and Media Studies Interested in This Major? Current Students: Visit us in Bolton Hall, Room 510B, call us at 414-229-4436 or email [email protected] Not a UWM Student yet? Call our Admissions Counselor at 414-229-7711 or email [email protected] Web: uwm.edu/journalism-advertising-media-studies JAMS at UWM Career Opportunities Media has never been more dynamic. The worlds JAMS students have a wide range of career paths open of journalism, advertising, public relations and film to them. Many seek careers in media, marketing, and are changing and growing at a rapid pace, and the communication. Others go on to pursue graduate work in the Department of Journalism, Advertising, and Media social sciences, humanities, and law. Studies (JAMS) is a great place to learn about them. Our alumni can be found in many prestigious organizations: Whether students see themselves working in news, entertainment, social media, advertising, public • Groupon • SC Johnson relations, or are fascinated by media, JAMS courses • Boston Globe • Milwaukee Brewers enable students to customize their education and • Milwaukee Journal • A.V. Club (Onion, Inc.) prepare for their chosen careers. Sentinel • WI Air National Guard Students choose courses to gain a broad • TMJ4 • United Nations understanding of the media’s place in society and • Foley & Lardner University culture, but also concentrate more closely in one of • Vice News • Boys & Girls Clubs of three areas: • WI State Legislature Greater Milwaukee Journalism. The Journalism concentration emphasizes • Bader Rutter writing, information gathering, critical thinking • New England Journal and technology skills in courses taught by media of Medicine • HSA Bank professionals. -

Developmental Reasoning and Planning with Robot Through Enactive Interaction with Human Maxime Petit

Developmental reasoning and planning with robot through enactive interaction with human Maxime Petit To cite this version: Maxime Petit. Developmental reasoning and planning with robot through enactive interaction with human. Automatic. Université Claude Bernard - Lyon I, 2014. English. NNT : 2014LYO10037. tel-01015288 HAL Id: tel-01015288 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01015288 Submitted on 26 Jun 2014 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. N˚d’ordre 37 - 2014 Année 2013 THESE DE L’UNIVERSITE DE LYON présentée devant L’UNIVERSITE CLAUDE BERNARD LYON 1 Ecole Doctorale Neurosciences et Cognition pour l’obtention du Diplôme de Thèse (arrété du 7 août 2006) Discipline : SCIENCES COGNITIVES Option : INFORMATIQUE présentée et soutenue publiquement le 6 Mars 2014 par Maxime Raisonnement et Planification Développementale d’un Robot via une Interaction Enactive avec un Humain Developmental Reasoning and Planning with Robot through Enactive Interaction with Human dirigée par Peter F. Dominey devant le jury composé de : Pr. Rémi Gervais Président du jury Pr. Giorgio Metta Rapporteur Pr. Philippe Gaussier Rapporteur Pr. Chrystopher Nehaniv Examinateur Dr. Jean-Christophe Baillie Examinateur Dr. Peter Ford Dominey Directeur de thèse 2 Stem-Cell and Brain Research Insti- École doctorale Neurosciences et Cog- tute, INSERM U846 nition (ED 476 - NSCo) 18, avenue Doyen Lepine UCBL - Lyon 1 - Campus de Gerland 6975 Bron Cedex 50, avenue Tony Garnier 69366 Lyon Cedex 07 Pour mon père. -

Chapter 1. “New Media” and Marshall Mcluhan: an Introduction

Chapter 1. “New Media” and Marshall McLuhan: An Introduction “Much of what McLuhan had to say makes a good deal more sense today than it did in 1964 because he was way ahead of his time.” - Okwor Nicholaas writing in the July 21, 2005 Daily Champion (Lagos, Nigeria) “I don't necessarily agree with everything I say." – Marshall McLuhan 1.1 Objectives of this Book The objective of this book is to develop an understanding of “new media” and their impact using the ideas and methodology of Marshall McLuhan, with whom I had the privilege of a six year collaboration. We want to understand how the “new media” are changing our world. We will also examine how the “new media” are impacting the traditional or older media that McLuhan (1964) studied in Understanding Media: Extensions of Man hereafter simply referred to simply as UM. In pursuing these objectives we hope to extend and update McLuhan’s life long analysis of media. One final objective is to give the reader a better understanding of McLuhan’s revolutionary body of work, which is often misunderstood and criticized because of a lack of understanding of exactly what McLuhan was trying to achieve through his work. Philip Marchand in an April 30, 2006 Toronto Star article unaware of my project nevertheless described my motivation for writing this book and the importance of McLuhan to understanding “new media”: Slowly but surely, McLuhan's star is rising. He's still not very respectable academically, but those wanting to understand the new technologies, from the iPod to the Internet, are going back to read what the master had to say about television and computers and the process of technological change in general. -

Sauterdivineansamplepages (Pdf)

The Decline of Space: Euclid between the Ancient and Medieval Worlds Michael J. Sauter División de Historia Centro de Investigación y Docencia Económicas, A.C. Carretera México-Toluca 3655 Colonia Lomas de Santa Fe 01210 México, Distrito Federal Tel: (+52) 55-5727-9800 x2150 Table of Contents List of Illustrations ............................................................................................................. iv Acknowledgments .............................................................................................................. v Preface ............................................................................................................................... vi Introduction: The divine and the decline of space .............................................................. 1 Chapter 1: Divinus absconditus .......................................................................................... 2 Chapter 2: The problem of continuity ............................................................................... 19 Chapter 3: The space of hierarchy .................................................................................... 21 Chapter 4: Euclid in Purgatory ......................................................................................... 40 Chapter 5: The ladder of reason ........................................................................................ 63 Chapter 6: The harvest of homogeneity ............................................................................ 98 Conclusion: The