JAUME PLENSA One Thought Fills Immensity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Salvador Dalí. De La Inmortal Obra De Cervantes

12 YEARS OF EXCELLENCE LA COLECCIÓN Salvador Dalí, Don Quijote, 2003. Salvador Dalí, Autobiografía de Ce- llini, 2004. Salvador Dalí, Los ensa- yos de Montaigne, 2005. Francis- co de Goya, Tauromaquia, 2006. Francisco de Goya, Caprichos, 2006. Eduardo Chillida, San Juan de la Cruz, 2007. Pablo Picasso, La Celestina, 2007. Rembrandt, La Biblia, 2008. Eduardo Chillida, So- bre lo que no sé, 2009. Francisco de Goya, Desastres de la guerra, 2009. Vincent van Gogh, Mon cher Théo, 2009. Antonio Saura, El Criti- cón, 2011. Salvador Dalí, Los can- tos de Maldoror, 2011. Miquel Bar- celó, Cahier de félins, 2012. Joan Miró, Homenaje a Gaudí, 2013. Joaquín Sorolla, El mar de Sorolla, 2014. Jaume Plensa, 58, 2015. Artika, 12 years of excellence Índice Artika, 12 years of excellence Index Una edición de: 1/ Salvador Dalí – Don Quijote (2003) An Artika edition: 1/ Salvador Dalí - Don Quijote (2003) Artika 2/ Salvador Dalí - Autobiografía de Cellini (2004) Avenida Diagonal, 662-664 2/ Salvador Dalí - Autobiografía de Cellini (2004) Avenida Diagonal, 662-664 3/ Salvador Dalí - Los ensayos de Montaigne (2005) 08034 Barcelona, Spain 3/ Salvador Dalí - Los ensayos de Montaigne (2005) 08034 Barcelona, España 4/ Francisco de Goya - Tauromaquia (2006) 4/ Francisco de Goya - Tauromaquia (2006) 5/ Francisco de Goya - Caprichos (2006) 5/ Francisco de Goya - Caprichos (2006) 6/ Eduardo Chillida - San Juan de la Cruz (2007) 6/ Eduardo Chillida - San Juan de la Cruz (2007) 7/ Pablo Picasso - La Celestina (2007) Summary 7/ Pablo Picasso - La Celestina (2007) Sumario 8/ Rembrandt - La Biblia (2008) A walk through twelve years in excellence in exclusive art book 8/ Rembrandt - La Biblia (2008) Un recorrido por doce años de excelencia en la edición de 9/ Eduardo Chillida - Sobre lo que no sé (2009) publishing, with unique and limited editions. -

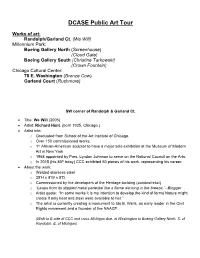

DCASE Public Art Self-Guided Tour Packet (PDF)

DCASE Public Art Tour Works of art: Randolph/Garland Ct. (We Will) Millennium Park: Boeing Gallery North (Screenhouse) (Cloud Gate) Boeing Gallery South (Christine Tarkowski) (Crown Fountain) Chicago Cultural Center: 78 E. Washington (Bronze Cow) Garland Court (Rushmore) SW corner of Randolph & Garland Ct. • Title: We Will (2005) • Artist: Richard Hunt, (born 1935, Chicago.) • Artist info: o Graduated from School of the Art Institute of Chicago. o Over 150 commissioned works. o 1st African-American sculptor to have a major solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York o 1968 appointed by Pres. Lyndon Johnson to serve on the National Council on the Arts. o In 2015 (his 80th bday) CCC exhibited 60 pieces of his work, representing his career. • About the work: o Welded stainless steel o 35’H x 8’W x 8’D o Commissioned by the developers of the Heritage building (condos/retail) o “Leaps from its stippled metal pedestal like a flame dancing in the breeze.”--Blogger o Artist quote: “In some works it is my intention to develop the kind of forms Nature might create if only heat and steel were available to her.” o The artist is currently creating a monument to Ida B. Wells, an early leader in the Civil Rights movement and a founder of the NAACP. (Walk to E side of CCC and cross Michigan Ave. at Washington to Boeing Gallery North, S. of Randolph, E. of Michigan) Millennium Park • Opened in 2004, the 24.5 acre Millennium Park was an industrial wasteland transformed into a world- class public park. -

Context Històric I Social: 1.1

LA DONA: "SUBJECTE" i "OBJECTE" DE L'OBRA D'ART. ANNEX I. 1.- Context històric i social: A la segona meitat del segle XIX, als països occidentals, es va portat a terme la consolidació dels moviments obrers: sindicats i partits polítics funcionaven per arreu. El 1873 es va produir una forta depressió econòmica que va durar aproximadament uns 10 anys i que va afectar les formes de vida i les pautes de conducta social. A la vegada va entrar en crisi la concepció positivista del món dominant fins aleshores. Fou una època en la qual el fet de ser dona havia de ser difícil. La burgesia havia agafat molta força i amb ella la institució matrimonial, perquè garantia hereus legítims als quals s’havia de deixar tot allò que el matrimoni havia acumulat. Per aquests motius la societat es guiava per rígits i severs codis sexuals patits sobretot per la dona. Els matrimonis ben poques vegades eren encara per amor, però això sí, la dona havia de ser totalment fidel. Amb el desenvolupament industrial i el creixement de la burgesia, s’havien portat ja a la pràctica els ideals dels il.lustrats. Tots els canvis econòmics i socials que es van produir a la primera meitat del segle van conduir a l’establiment d’una forma ritual-simbòlica del paper de la dona a la nova societat industrial. Fou llavors quan es separaren definitivament els dos móns: el món privat de la llar, de la familia, i el món públic, de la societat. La dona va quedar reclüida definitivament en el primer i totalment exclosa del segon, reservat únicament i exclussivament per als homes. -

Catalan Modernism and Vexillology

Catalan Modernism and Vexillology Sebastià Herreros i Agüí Abstract Modernism (Modern Style, Modernisme, or Art Nouveau) was an artistic and cultural movement which flourished in Europe roughly between 1880 and 1915. In Catalonia, because this era coincided with movements for autonomy and independence and the growth of a rich bourgeoisie, Modernism developed in a special way. Differing from the form in other countries, in Catalonia works in the Modern Style included many symbolic elements reflecting the Catalan nationalism of their creators. This paper, which follows Wladyslaw Serwatowski’s 20 ICV presentation on Antoni Gaudí as a vexillographer, studies other Modernist artists and their flag-related works. Lluís Domènech i Montaner, Josep Puig i Cadafalch, Josep Llimona, Miquel Blay, Alexandre de Riquer, Apel·les Mestres, Antoni Maria Gallissà, Joan Maragall, Josep Maria Jujol, Lluís Masriera, Lluís Millet, and others were masters in many artistic disciplines: Architecture, Sculpture, Jewelry, Poetry, Music, Sigillography, Bookplates, etc. and also, perhaps unconsciously, Vexillography. This paper highlights several flags and banners of unusual quality and national significance: Unió Catalanista, Sant Lluc, CADCI, Catalans d’Amèrica, Ripoll, Orfeó Català, Esbart Català de Dansaires, and some gonfalons and flags from choral groups and sometent (armed civil groups). New Banner, Basilica of the Monastery of Santa Maria de Ripoll Proceedings of the 24th International Congress of Vexillology, Washington, D.C., USA 1–5 August 2011 © 2011 North American Vexillological Association (www.nava.org) 506 Catalan Modernism and Vexillology Background At the 20th International Conference of Vexillology in Stockholm in 2003, Wladyslaw Serwatowski presented the paper “Was Antonio Gaudí i Cornet (1852–1936) a Vexillographer?” in which he analyzed the vexillological works of the Catalan architectural genius Gaudí. -

Del Romanticisme Al Modernisme

primeres 1 a 24 29/9/06 12:52 Página 2 Del Romanticisme al Modernisme Col·lecció de Pintura del Museu Diocesà de Barcelona Organització: Català · Castellano primeres 1 a 24 29/9/06 12:52 Página 4 Del Romanticisme al Modernisme Col·lecció de Pintura del Museu Diocesà de Barcelona Museu Diocesà de Barcelona Del 6 d’octubre al 5 de novembre de 2006 primeres 1 a 24 29/9/06 12:52 Página 8 Índex Presentacions 11 Vicente Sala Belló Josep M. Martí Bonet Pintura dels segles XIX i XX del Museu Diocesà de Barcelona 17 Francesc Fontbona Índex d’artistes 21 Catàleg d’obra 23 Bibliografia 181 Versión en castellano 183 primeres 1 a 24 29/9/06 12:52 Página 10 Vicente Sala Belló President de la Caja de Ahorros del Mediterráneo La Caja de Ahorros del Mediterráneo continua apostant fermament per una políti- ca de patrocini cultural com un servei a la societat actual, avui dia enormement sen- sibilitzada envers aquest àmbit. I més concretament, la nostra Obra Social es plan- teja prioritàriament la coneixença i la divulgació de la cultura mediterrània, de la qual la mostra que avui presentem és un exponent prou clar, en un dels camps de la creació tan fonamental com és la pintura. Novament gaudim del marc incomparable del monument de la Pia Almoina de Barcelona, seu del Museu Diocesà, per presentar l’exposició “Del Romanticisme al Modernisme”. És per a nosaltres tot un honor poder oferir al públic aquesta magní- fica col·lecció de pintura a cavall dels segles XIX i XX. -

Jaume Plensa Solo Exhibitions

JAUME PLENSA l SOLO EXHIBITIONS (Selection) www.jaumeplensa.com 2021 Slowness. Galleri Andersson/Sandström, Stockholm, Sweden The True Portrait. Galerie Lelong & Co., Paris (online show) 2020 La Llarga Nit. Galeria Senda, Barcelona, Spain Nocturne. Gray Warehouse, Chicago, Illinois, USA Jaume Plensa. Plaza del Estadio de la Cerámica, Villarreal, Castellón, Spain Jaume Plensa, Invisibles. Gray Gallery, Chicago, viewing room (online show) Jaume Plensa. Galerie Lelong & Co., Paris (online show) Jaume Plensa: April is the cruelest month. Galerie Lelong & Co., New York, viewing room (online show) 2019 Jaume Plensa. Jakobshallen – Galerie Scheffel, Bad Homburg, Germany Jaume Plensa. Plaça del Congrés Eucarístic, Elche, Alicante, Spain Behind the Walls / Detrás del Muro. Organized by MUNAL–Museo Nacional de Arte, INBAL–Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes y Literatura in collaboration with Fundación Callia, Ciudad de Mexico Jaume Plensa. Galerie Lelong & Co., Paris, France Talking Continents. Arthur Ross Gallery at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA Jaume Plensa. MMOMA–Moscow Museum of Modern Art, Moscow, Russia Jaume Plensa. Ciutat de les Arts i les Ciències, Valencia, Spain Jaume Plensa. Museum Beelden aan Zee, The Hague, Netherlands Jaume Plensa a Montserrat. Museu de Montserrat, Abadia de Montserrat, Barcelona, Spain Talking Continents. Telfair Museums, Jepson Center for the Arts, Savannah, Georgia, USA Jaume Plensa. Galería Pilar Serra, Madrid, Spain Jaume Plensa, Nouvelles estampes. Galerie Lelong & Co., Paris, France 2018 Jaume Plensa. MACBA–Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain Invisibles. Palacio de Cristal, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid, Spain Talking Continents. Memphis Brooks Museum of Art, Memphis, Tennessee, USA Jaume Plensa. Galleri Andersson/Sandström, Stockholm, Sweden La Música Gráfica de Jaume Plensa. -

Bay Area Economics Draft Report – Study Of

DRAFT REPORT Study of Alternatives to Housing For the Funding of Brooklyn Bridge Park Operations Presented by: BAE Urban Economics Presented to: Brooklyn Bridge Park Committee on Alternatives to Housing (CAH) February 22, 2011 Table of Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................................... i Introduction and Approach ........................................................................................... 1 Committee on Alternatives to Housing (CAH) Process ............................................................ 1 Report Purpose and Organization ............................................................................................. 2 Topics Outside the Scope of the CAH and this Report ............................................................. 3 Report Methodology ................................................................................................................. 4 Limiting Conditions .................................................................................................................. 4 Park Overview and the Current Plan ............................................................................ 5 The Park Setting and Plan ......................................................................................................... 5 Park Governance ....................................................................................................................... 6 The Current Financing Plan ..................................................................................................... -

Masters Thesis

WHERE IS THE PUBLIC IN PUBLIC ART? A CASE STUDY OF MILLENNIUM PARK A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Corrinn Conard, B.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2008 Masters Examination Committee: Approved by Dr. James Sanders III, Advisor Advisor Professor Malcolm Cochran Graduate Program in Art Education ABSTRACT For centuries, public art has been a popular tool used to celebrate heroes, commemorate historical events, decorate public spaces, inspire citizens, and attract tourists. Public art has been created by the most renowned artists and commissioned by powerful political leaders. But, where is the public in public art? What is the role of that group believed to be the primary client of such public endeavors? How much power does the public have? Should they have? Do they want? In this thesis, I address these and other related questions through a case study of Millennium Park in Chicago. In contrast to other studies on this topic, this thesis focuses on the perspectives and opinions of the public; a group which I have found to be scarcely represented in the literature about public participation in public art. To reveal public opinion, I have conducted a total of 165 surveys at Millennium Park with both Chicago residents and tourists. I have also collected the voices of Chicagoans as I found them in Chicago’s major media source, The Chicago Tribune . The collection of data from my research reveal a glimpse of the Chicago public’s opinion on public art, its value to them, and their rights and roles in the creation of such endeavors. -

Jaume Plensa: Talking SAVANNAH

VISUAL ARTS Jaume Plensa: Talking SAVANNAH Continents Fri, March 01– Sun, June 09, 2019 Venue Jepson Center for the Arts, 207 W York St, Savannah, GA 31401 View map Admission Buy tickets More information Telfair Museums Credits Presented by Telfair Museums. Image: Talking Continents by Jaume Plensa, 2013 (photo by David Jaume Plensa presents large-scale sculptures and Nevala) installations that use language, history, literature, and psychology to draw attention to the barriers that separate and divide humanity. In Talking Continents, Jaume Plensa (Spanish, b. 1955) used stainless steel to create a floating archipelago of 19 cloud-like shapes. The biomorphic forms are made with die-cut letters taken from nine different languages that refuse to come together as words, existing instead as abstract forms, and also arbitrary signs and signifiers. Many of the suspended sculptures appear as orbs or islands, while others include human figures in pensive, vulnerable postures. The sculptures speak to the diversity of language and culture, but also gesture toward global interconnectedness as a path to tolerance and acceptance. Visitors are encouraged to tap into the artist’s notion of universal understanding by thinking about the ways in which we are linked together as a collective humanity. ABOUT JAUME PLENSA Born in 1955 in Barcelona, Jaume Plensa is one of the world’s foremost sculptors with international exhibitions and over thirty public projects spanning the globe in such cities as Chicago, Dubai, London, Liverpool, Montreal, Nice, San Diego, Tokyo, Toronto, and Vancouver. Plensa’s work has been the subject of solo exhibitions at museums Embassy of Spain – Cultural Office | 2801 16th Street, NW, Washington, D.C. -

LUCAS CULTURAL ARTS MUSEUM MAYOR’S TASK FORCE REPORT | CHICAGO May 16, 2014

THE LUCAS CULTURAL ARTS MUSEUM MAYOR’S TASK FORCE REPORT | CHICAGO May 16, 2014 Mayor Rahm Emanuel City Hall - 121 N LaSalle St. Chicago, IL 60602 Dear Mayor Emanuel, As co-chairs of the Lucas Cultural Arts Museum Site Selection Task Force, we are delighted to provide you with our report and recommendation for a site for the Lucas Cultural Arts Museum. The response from Chicagoans to this opportunity has been tremendous. After considering more than 50 sites, discussing comments from our public forum and website, reviewing input from more than 300 students, and examining data from myriad sources, we are thrilled to recommend a site we believe not only meets the criteria you set out but also goes beyond to position the Museum as a new jewel in Chicago’s crown of iconic sites. Our recommendation offers to transform existing parking lots into a place where students, families, residents, and visitors from around our region and across the globe can learn together, enjoy nature, and be inspired. Speaking for all Task Force members, we were both honored to be asked to serve on this Task Force and a bit awed by your charge to us. The vision set forth by George Lucas is bold, and the stakes for Chicago are equally high. Chicago has a unique combination of attributes that sets it apart from other cities—a history of cultural vitality and groundbreaking arts, a tradition of achieving goals that once seemed impossible, a legacy of coming together around grand opportunities, and not least of all, a setting unrivaled in its natural and man-made beauty. -

The Crown Fountain in Chicago's Millennium Park Is an Ingenious

ACrowning Achievement The Crown Fountain in Chicago’s Millennium Park is an ingenious fusion of artistic vision and high-tech water effects in which sculptor Jaume Plensa’s creative concepts were brought to life by an interdisciplinary team that included the waterfeature designers at Crystal Fountains. Here, Larry O’Hearn describes how the firm met the challenge and helped give Chicago’s residents a defining landmark in glass, light, water and bright faces. 50 WATERsHAPES ⅐ APRIL 2005 ByLarry O’Hearn In July last year, the city of Chicago unveiled its newest civic landmark: Millennium Park, a world-class artistic and architec- tural extravaganza in the heart of downtown. At a cost of more than $475 million and in a process that took more than six years to complete, the park transformed a lakefront space once marked by unsightly railroad tracks and ugly parking lots into a civic showcase. The creation of the 24.5-acre park brought together an unprecedented collection of world-class artists, architects, urban planners, landscape architects and designers including Frank Gehry, Anish Kapoor and Kathryn Gustafson. Each con- tributed unique designs that make powerful statements about the ambition and energy that define Chicago. One of the key features of Millennium Park is the Crown Fountain. Designed by Jaume Plensa, the Spanish- born sculptor known for installations that focus on human experiences that link past, present and fu- ture and for a philosophy that says art should not simply decorate an area but rather should trans- form and regenerate it, the Crown Fountain began with the notion that watershapes such as this one need to be gathering places. -

La Trajectòria Professional Del Fotògraf Francesc Serra I Dimas (1877 – 1967)

La trajectòria professional del fotògraf Francesc Serra i Dimas (1877 – 1967) Autora: Carla Arbós Valls Director: Bonaventura Bassegoda Hugas Màster Anàlisi i Gestió del Patrimoni Artístic Departament d’Art i de Musicologia . Facultat de Filosofia i Lletres Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona . 2017-201 - Uno ha asistido a nada menos que al traspaso de un siglo. Y no de una manera indiferente ¿Vé usted? En mi archivo guardo 50 mil fichas. Toda una época vive, palpita, se anima con solo ir al laboratorio y operar en las placas con los ácidos. Eso ¿no es hermoso?¿No es bello poder fijar los recuerdos? Francesc Serra i Dimas, 1964 Agraïments Primerament, voldria agrair a totes aquelles persones que de manera directa o indirecta s’han involucrat en la realització d’aquest Treball de Final de Màster, ja que sense la seva col·laboració i dedicació, no hagués estat possible dur-lo a terme. Moltes gràcies, doncs, al director d’aquesta tesi el Professor Bonaventura Bassegoda, per guiar- me, aconsellar-me i indicar-me a qui i on acudir al llarg d’aquesta investigació, i també per la confiança dipositada i l’empenta rebuda; i a la Núria Llorens, coordinadora del màster Anàlisi i Gestió del Patrimoni Artístic de la Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, per assenyalar-me un tema de recerca que s’ha adequat perfectament al meu bagatge acadèmic entorn de l’art i la fotografia, com també per la seva disposició i gran amabilitat en tot moment. Per altra banda, voldria expressar la meva més sincera gratitud als familiars de Francesc Serra Dimas, als qui els hi dedico aquesta memòria, per la seva confiança i proximitat, per obrir-me les portes de casa seva i rebrem tan amablement.