Abstract Extracts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Native Title Information Talk Delivered at Fernvale Futures on 22 February 2014. Tim Wishart Slide 1 I Acknowledge and Offer M

A Native Title Information Talk Delivered at Fernvale Futures on 22 February 2014. Tim Wishart Slide 1 I acknowledge and offer my respect to the country on which we meet and to the Traditional Owners of this country and to their Old People and Elders. The organisation for which I work, Queensland South Native Title Services is a native title service provider recognised and funded by the Federal Government under the Native Title Act (1993). Slide 2 The area for which QSNTS has statutory recognition under the Native Title Act covers an area spanning Queensland, along the New South Wales border from the Coral Sea to the South Australian border, north to about 250 kilometres north of Mt Isa and running diagonally south eastwards to the coast, marginally south of Sarina. Slide 3 I ought to say that views and opinions expressed are mine and are not necessarily reflective of corporate views or policy of QSNTS. In this conversation I will refer to the Native Title Act as ‘the Act’. But in the consciousness of Queensland Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander society, the expression “the Act” is often a reference to The Aboriginal Protection and Restrictions of the Sale of Opium Act 1897. That legislation was an Act of the Queensland Parliament. As a result of dispersal, malnutrition, use of opium and diseases, all a consequence of European incursion into traditional lands coupled with the attempted genocide that came with that incursion, it was widely believed in Queensland that Aborigines were members of a 'dying race'. In 1894 pressure from some quarters of the community saw the Queensland Government commission Archibald Meston to look at what had conveniently, for the colonising power, become the plight of Aboriginal people. -

Many Voices Queensland Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Languages Action Plan

Yetimarala Yidinji Yi rawarka lba Yima Yawa n Yir bina ach Wik-Keyangan Wik- Yiron Yam Wik Pa Me'nh W t ga pom inda rnn k Om rungu Wik Adinda Wik Elk Win ala r Wi ay Wa en Wik da ji Y har rrgam Epa Wir an at Wa angkumara Wapabura Wik i W al Ng arra W Iya ulg Y ik nam nh ar nu W a Wa haayorre Thaynakwit Wi uk ke arr thiggi T h Tjung k M ab ay luw eppa und un a h Wa g T N ji To g W ak a lan tta dornd rre ka ul Y kk ibe ta Pi orin s S n i W u a Tar Pit anh Mu Nga tra W u g W riya n Mpalitj lgu Moon dja it ik li in ka Pir ondja djan n N Cre N W al ak nd Mo Mpa un ol ga u g W ga iyan andandanji Margany M litja uk e T th th Ya u an M lgu M ayi-K nh ul ur a a ig yk ka nda ulan M N ru n th dj O ha Ma Kunjen Kutha M ul ya b i a gi it rra haypan nt Kuu ayi gu w u W y i M ba ku-T k Tha -Ku M ay l U a wa d an Ku ayo tu ul g m j a oo M angan rre na ur i O p ad y k u a-Dy K M id y i l N ita m Kuk uu a ji k la W u M a nh Kaantju K ku yi M an U yi k i M i a abi K Y -Th u g r n u in al Y abi a u a n a a a n g w gu Kal K k g n d a u in a Ku owair Jirandali aw u u ka d h N M ai a a Jar K u rt n P i W n r r ngg aw n i M i a i M ca i Ja aw gk M rr j M g h da a a u iy d ia n n Ya r yi n a a m u ga Ja K i L -Y u g a b N ra l Girramay G al a a n P N ri a u ga iaba ithab a m l j it e g Ja iri G al w i a t in M i ay Giy L a M li a r M u j G a a la a P o K d ar Go g m M h n ng e a y it d m n ka m np w a i- u t n u i u u u Y ra a r r r l Y L a o iw m I a a G a a p l u i G ull u r a d e a a tch b K d i g b M g w u b a M N n rr y B thim Ayabadhu i l il M M u i a a -

Southern and Western Queensland Region

138°0'E 140°0'E 142°0'E 144°0'E 146°0'E 148°0'E 150°0'E 152°0'E 154°0'E DOO MADGE E S (! S ' ' 0 Gangalidda 0 ° QUD747/2018 ° 8 8 1 Waanyi People #2 & Garawa 1 (QC2018/004) People #2 Warrungnu [Warrungu] Girramay People Claimant application and determination boundary data compiled from NNTT based on boundaries with areas excluded or discrete boundaries of areas being claimed) as determination, a search of the Tribunal's registers and data sourced from Department of Resources (Qld) © The State of Queensland for they have been recognised by the Federal Court process. databases is required. Further information is available from the Tribunals website at GE ORG E TO W N People #2 Girramay Gkuthaarn and (! People #2 (! CARDW EL L that portion where their data has been used. Where the boundary of an application has been amended in the Federal Court, the www.nntt.gov.au or by calling 1800 640 501 Kukatj People map shows this boundary rather than the boundary as per the Register of Native Title © Commonwealth of Australia 2021 CARPENTARIA Tagalaka Southern and WesternQ UD176/2T0o2p0ographic vector data is © Commonwealth of Australia (Geoscience Australia) Claims (RNTC), if a registered application. The Registrar, the National Native Title Tribunal and its staff, members and agents Ewamian People QUD882/2015 Gurambilbarra Wulguru2k0a1b5a. Mada Claim The applications shown on the map include: and the Commonwealth (collectively the Commonwealth) accept no liability and give People #3 GULF REGION Warrgamay People (QC2020/N00o2n) freehold land tenure sourced from Department of Resources (QLD) March 2021. -

Suicide Prevention for LGBTIQ+ Communities Learnings from the National Suicide Prevention Trial

Science. Compassion. Action. Suicide prevention for LGBTIQ+ communities Learnings from the National Suicide Prevention Trial April 2021 Suicide prevention for LGBTIQ+ communities: Learnings from the National Suicide Prevention Trial ii Acknowledgements Black Dog Institute Black Dog Institute would like to acknowledge Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as Australia’s First People and Traditional Custodians. We value their cultures, identities, and continuing connection to country, waters, kin and community. We pay our respects to Elders past and present and are committed to making a positive contribution to the mental health and wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people across Australia. Brisbane North PHN We acknowledge the traditional custodians of this land, the Turrbal and Jagera People of Brisbane, the Gubbi Gubbi people of Caboolture and Bribie Island, the Waka Waka people of Kilcoy and the Ningy Ningy people of Redcliffe. We pay our respects to Elders past, present and emerging for they hold the memories, the traditions, the culture and the hopes of Aboriginal Australia. North Western Melbourne PHN We would like to acknowledge the Wurundjeri People, the Boonerwrung People and the Wathaurong People as the traditional custodians of the land on which our work takes place. We pay our respects to Elders past, present and emerging. Acknowledgement of lived experience We acknowledge those contributing to suicide prevention efforts who are survivors of a suicide attempt, have experienced suicidal behaviour, or have been bereaved or impacted by suicide. Your insights and contributions are critical. Thank you The Black Dog Institute thanks the interviewees and other stakeholders from the Brisbane North Primary Health Network (PHN), North Western Melbourne PHN and the LGBTIQ+ Health Australia for their contributions to the development of this document. -

Annual Report 2007–2008

07 08 NATIONAL NATIVE TITLE TRIBUNAL CONTACT DETAILS Annual Report 2007–2008 Tribunal National Native Title PRINCIPAL REGISTRY (PERTH) NEW SOUTH WALES AND AUSTRALIAN Level 4, Commonwealth Law Courts Building CAPITAL TERRITORY 1 Victoria Avenue Level 25 Perth WA 6000 25 Bligh Street Sydney NSW 2000 GPO Box 9973, Perth WA 6848 GPO Box 9973, Sydney NSW 2001 Telephone: (08) 9268 7272 Facsimile: (08) 9268 7299 Telephone: (02) 9235 6300 Facsimile: (02) 9233 5613 VICTORIA AND TASMANIA Level 8 SOUTH AUSTRALIA 310 King Street Level 10, Chesser House Annual Report Melbourne Vic. 3000 91 Grenfell Street Adelaide SA 5000 GPO Box 9973, Melbourne Vic. 3001 GPO Box 9973, Adelaide SA 5001 Telephone: (03) 9920 3000 2007–2008 Facsimile: (03) 9606 0680 Telephone: (08) 8306 1230 Facsimile: (08) 8224 0939 NORTHERN TERRITORY Level 5, NT House WESTERN AUSTRALIA 22 Mitchell Street Level 11, East Point Plaza Darwin NT 0800 233 Adelaide Terrace Perth WA 6000 GPO Box 9973, Darwin NT 0801 GPO Box 9973, Perth WA 6848 Telephone: (08) 8936 1600 Facsimile: (08) 8981 7982 Telephone: (08) 9268 9700 Facsimile: (08) 9221 7158 QUEENSLAND Level 30, 239 George Street NATIONAL FREECALL NUMBER: 1800 640 501 Brisbane Qld 4000 WEBSITE: www.nntt.gov.au GPO Box 9973, Brisbane Qld 4001 National Native Title Tribunal office hours: Telephone: (07) 3226 8200 8.30am – 5.00pm Facsimile: (07) 3226 8235 8.00am – 4.30pm (Northern Territory) CAIRNS (REGIONAL OFFICE) Level 14, Cairns Corporate Tower 15 Lake Street Cairns Qld 4870 PO Box 9973, Cairns Qld 4870 Telephone: (07) 4048 1500 Facsimile: (07) 4051 3660 Resolution of native title issues over land and waters. -

13 Relationship and Communality: an Indigenous

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sydney eScholarship 13 RELATIONSHIP AND COMMUNALITY: AN INDIGENOUS PERSPECTIVE ON KNOWLEDGE AND EXPRESSION Maroochy Barambah1 PROFESSOR ANNE FITZGERALD We’re going to talk about indigenous peoples and law, and this session is going to be chaired by Dr Terry Cutler. I don’t think Terry needs any further introduction to you, and I’m sure this is going to be a fascinating session. Maroochy Barambah and Ade Kukoyi have been known to me and Brian for many years. In fact I actually first met Maroochy in New York when she was studying opera singing there. The film in which she starred, Black River, had actually just won the Paris Opera Film of the Year Award. The commentator for this session will be Professor Susy Frankel from New Zealand, who’s been very much involved with indigenous IP issues in New Zealand. Terry, over to you. DR TERRY CUTLER Thank you Anne. It gives me huge pleasure to chair this session. At the beginning of our conference we had a very moving welcome to country. Then we tend to proceed to marginalise, or make very unwelcome, any discussion that isn’t within an Anglo-Saxon, or a Commonwealth Club framework. I think one of the great gaps in public policy discussion in Australia is our neglect of this whole area of traditional knowledge and the role of indigenous people in intellectual property discussions. This is even worse I 1 Maroochy Barambah is an Australian Aboriginal mezzo-soprano singer and songwoman and law-woman of the Turrbal-Dippil people from the Brisbane region. -

SCHHS Profile | Sunshine Coast Hospital And

Sunshine Coast Hospital and Health Service Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health Cultural capability Achieving sustainable health gains for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Queenslanders is a core responsibility and high priority for the whole health sector (Everyone’s Business) and is a guiding Significant events principle of Making Tracks towards closing the gap by 2033. The SCHHS supports and engages in celebrations that promote and recognise Aboriginal and Torres Strait The Sunshine Coast Hospital and Health Service Islander Culture (SCHHS) acknowledges the Traditional Owners, the Gubbi Gubbi people, of the Sunshine Coast and • Apology Day Gympie Regions which the Sunshine Coast Hospital • Closing the Gap and Health Service covers. • NAIDOC Population Programs The population data below is based on the 2011 Census of Population and Housing question about • Cultural Practice Program (Mandatory) - To Indigenous status. Please note that the boundaries develop the knowledge and skills that will enable used to determine this information may not be exact, each person to best contribute through their and the data is approximate. roles in the workplace towards improving health outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander • 6,060 persons (or 1.6 per cent) were Aboriginal people and Torres Strait Islander peoples (compared to • Deadly Young Persons Program 3.6 per cent in Queensland) • Cultural Healing Program • 39.1 per cent of Aboriginal and Torres Strait • Come Gather Program (nutrition). Islander peoples were aged 0 to 14 years (compared to 18.8 per cent of non-Indigenous persons) Clinics • 3.4 per cent of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were aged 65 years and over • Flu and Pneumonia (March –June) (compared to 13.4 per cent of non-Indigenous • Respiratory Health persons). -

2019 Queensland Bushfires State Recovery Plan 2019-2022

DRAFT V20 2019 Queensland Bushfires State Recovery Plan 2019-2022 Working to recover, rebuild and reconnect more resilient Queensland communities following the 2019 Queensland Bushfires August 2020 to come Document details Interpreter Security classification Public The Queensland Government is committed to providing accessible services to Queenslanders from all culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds. If you have Date of review of security classification August 2020 difficulty in understanding this report, you can access the Translating and Interpreting Authority Queensland Reconstruction Authority Services via www.qld.gov.au/languages or by phoning 13 14 50. Document status Final Disclaimer Version 1.0 While every care has been taken in preparing this publication, the State of Queensland accepts no QRA reference QRATF/20/4207 responsibility for decisions or actions taken as a result of any data, information, statement or advice, expressed or implied, contained within. ISSN 978-0-9873118-4-9 To the best of our knowledge, the content was correct at the time of publishing. Copyright Copies This publication is protected by the Copyright Act 1968. © The State of Queensland (Queensland Reconstruction Authority), August 2020. Copies of this publication are available on our website at: https://www.qra.qld.gov.au/fitzroy Further copies are available upon request to: Licence Queensland Reconstruction Authority This work is licensed by State of Queensland (Queensland Reconstruction Authority) under a Creative PO Box 15428 Commons Attribution (CC BY) 4.0 International licence. City East QLD 4002 To view a copy of this licence, visit www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Phone (07) 3008 7200 In essence, you are free to copy, communicate and adapt this annual report, as long as you attribute [email protected] the work to the State of Queensland (Queensland Reconstruction Authority). -

Chapter 12 - Table of Contents

Cultural Heritage 12 DRAFT Chapter 12 - Table of Contents VERSION CONTROL: 28/06/2017 12 Cultural Heritage 12-1 12.1 Introduction 12-1 12.2 Indigenous Cultural Heritage 12-2 12.2.1 Statutory Framework 12-2 12.2.2 Paleo environment 12-5 12.2.3 Register Searches 12-6 12.2.4 Predicted Findings 12-13 12.3 Non-Indigenous Cultural Heritage 12-14 12.3.1 Statutory Framework 12-15 12.3.2 Results of Register Searches 12-19 12.3.3 Archaeological Potential 12-26 12.3.4 Significance Assessment 12-26 12.4 Potential Impacts and Mitigation Measures 12-30 12.5 Summary 12-31 Page i Draft EIS: 28/06/2017 List of Figures Figure 12-1. Location of the three shell middens recorded in the DATSIP database on or near Lindeman Island. ......................................................................................................................................... 12-6 Figure 12-2. DATSIP search results for the broader Whitsunday area. ....................................................... 12-11 Figure 12-3. Adderton 1898 home with residence on left and woolshed and yards on right. Photo taken in 1923 (Source Blackwood 1997, p. 131). .................................................................... 12-20 Figure 12-4. Tents and Home Beach 1928 (State Library Queensland). ..................................................... 12-21 Figure 12-5. Home Beach 1941 (QGTB Brochure, 1941). ........................................................................... 12-22 Figure 12-6. Accommodation circa 1960 (JOL, Record #371532). ............................................................. -

Monitoring Indigenous Heritage Within the Reef 2050 Integrated

© Commonwealth of Australia (Australian Institute of Marine Science) 2019 Published by the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority ISBN 978-0-6485892-0-4 This document is licensed for use under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International licence with the exception of the Coat of Arms of the Commonwealth of Australia, the logos of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority and the Queensland Government, any other material protected by a trademark, content supplied by third parties and any photographs. For licence conditions see: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by- nc/4.0/ A catalogue record for this publication is available from the National Library of Australia. This publication should be cited as: Jarvis, D., Hill, R., Buissereth, R., Moran, C., Talbot, L.D., Bullio, R., Grant, C., Dale, A., Deshong, S., Fraser, D., Gooch, M., Hale, L., Mann, M., Singleton, G. and Wren, L., 2019, Monitoring the Indigenous heritage within the Reef 2050 Integrated Monitoring and Reporting Program: Final Report of the Indigenous Heritage Expert Group, Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, Townsville. Front cover image: Aerial drone image of Sawmill Beach, Whitsundays. © Commonwealth of Australia (GBRMPA), Photographer: Andrew Denzin. DISCLAIMER While reasonable effort has been made to ensure that the contents of this publication are factually correct, the Commonwealth of Australia, represented by the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, does not accept responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the contents, and shall not be liable for any loss or damage that may be occasioned directly or indirectly through the use of, or reliance on, the contents of this publication. -

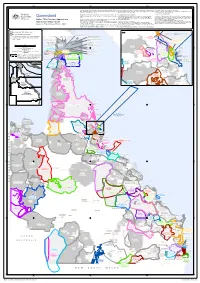

Queensland for That Map Shows This Boundary Rather Than the Boundary As Per the Register of Native Title Databases Is Required

140°0'E 145°0'E 150°0'E Claimant application and determination boundary data compiled from NNTT based on Where the boundary of an application has been amended in the Federal Court, the determination, a search of the Tribunal's registers and data sourced from Department of Resources (Qld) © The State of Queensland for that map shows this boundary rather than the boundary as per the Register of Native Title databases is required. Further information is available from the Tribunals website at portion where their data has been used. Claims (RNTC), if a registered application. www.nntt.gov.au or by calling 1800 640 501 © Commonwealth of Australia 2021 Topographic vector data is © Commonwealth of Australia (Geoscience Australia) 2006. The applications shown on the map include: Maritime boundaries data is © Commonwealth of Australia (Geoscience Australia) - registered applications (i.e. those that have complied with the registration test), The Registrar, the National Native Title Tribunal and its staff, members and agents and Queensland 2006. - new and/or amended applications where the registration test is being applied, the Commonwealth (collectively the Commonwealth) accept no liability and give no - unregistered applications (i.e. those that have not been accepted for registration), undertakings guarantees or warranties concerning the accuracy, completeness or As part of the transitional provisions of the amended Native Title Act in 1998, all - compensation applications. fitness for purpose of the information provided. Native Title Claimant Applications applications were taken to have been filed in the Federal Court. In return for you receiving this information you agree to release and Any changes to these applications and the filing of new applications happen through Determinations shown on the map include: indemnify the Commonwealth and third party data suppliers in respect of all claims, and Determination Areas the Federal Court. -

A Linguistic Bibliography of Aboriginal Australia and the Torres Strait Islands

OZBIB: a linguistic bibliography of Aboriginal Australia and the Torres Strait Islands Dedicated to speakers of the languages of Aboriginal Australia and the Torres Strait Islands and al/ who work to preserve these languages Carrington, L. and Triffitt, G. OZBIB: A linguistic bibliography of Aboriginal Australia and the Torres Strait Islands. D-92, x + 292 pages. Pacific Linguistics, The Australian National University, 1999. DOI:10.15144/PL-D92.cover ©1999 Pacific Linguistics and/or the author(s). Online edition licensed 2015 CC BY-SA 4.0, with permission of PL. A sealang.net/CRCL initiative. PACIFIC LINGUISTICS FOUNDING EDITOR: Stephen A. Wurm EDITORIAL BOARD: Malcolm D. Ross and Darrell T. Tryon (Managing Editors), John Bowden, Thomas E. Dutton, Andrew K. Pawley Pacific Linguistics is a publisher specialising in linguistic descriptions, dictionaries, atlases and other material on languages of the Pacific, the Philippines, Indonesia and Southeast Asia. The authors and editors of Pacific Linguistics publications are drawn from a wide range of institutions around the world. Pacific Linguistics is associated with the Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies at The Australian NatIonal University. Pacific Linguistics was established in 1963 through an initial grant from the Hunter Douglas Fund. It is a non-profit-making body financed largely from the sales of its books to libraries and individuals throughout the world, with some assistance from the School. The Editorial Board of Pacific Linguistics is made up of the academic staff of the School's Department of Linguistics. The Board also appoints a body of editorial advisors drawn from the international community of linguists.