Demography, Urbanization and Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Urbanization with and Without Industrialization∗

Urbanization with and without Industrialization∗ a Douglas GOLLIN Rémi JEDWABb Dietrich VOLLRATHc a Department of International Development, University of Oxford b Department of Economics, George Washington University c Department of Economics, University of Houston This Version: October 1st, 2013 Abstract: Many theories link urbanization with industrialization; in partic- ular, with the production of tradable (and typically manufactured) goods. We document that the expected relationship between urbanization and the level of industrialization is not present in a sample of developing economies. The breakdown occurs due to a large sub-sample of resource exporters that have urbanized without increasing output in either manufacturing or in- dustrial services such as finance. To account for these stylized facts, we construct a model of structural change that accommodates two different paths to high urbanization rates. The first involves the typical movement of labor from agriculture into industry, as in many models of structural change; this stylized pattern leads to what we term “production cities” that produce tradable goods. The second path is driven by the income effect of natural resource endowments: resource rents are spent on urban goods and services, which gives rise to “consumption cities” that are made up pri- marily of workers in non-tradable services. We document empirically that there is such a distinction in the employment composition of cities between developing countries that rely on natural resource exports and those that do not. Our model and the supporting data suggest that urbanization is not a homogenous event, and this has possible implications for long-run growth. Keywords: Structural Change; Urbanization; Industrialization JEL classification: L16; N10; N90; O18; O41; R10 ∗Douglas Gollin, University of Oxford (e-mail: [email protected]). -

DPCC Country Codes V1.2 (PDF)

DPCC Country Codes List v1.2 DPCC Country Codes List v1.2 - ISO 3166 Standard DPCC State Province Codes List v1.2 - ISO 3166-2 Standard ISO Country Name ISO Country Code NCBI Country Name ISO Country Name ISO Country Code ISO State Province Code ISO State Province Name Afghanistan AFG Afghanistan United States of America USA US-AL Alabama Aland Islands ALA United States of America USA US-AK Alaska Albania ALB Albania United States of America USA US-AZ Arizona Algeria DZA Algeria United States of America USA US-AR Arkansas American Samoa ASM American Samoa United States of America USA US-CA California Andorra AND Andorra United States of America USA US-CO Colorado Angola AGO Angola United States of America USA US-CT Connecticut Anguilla AIA Anguilla United States of America USA US-DE Delaware Antarctica ATA Antarctica United States of America USA US-DC District of Columbia Antigua and Barbuda ATG Antigua and Barbuda United States of America USA US-FL Florida Argentina ARG Argentina United States of America USA US-GA Georgia Armenia ARM Armenia United States of America USA US-HI Hawaii Aruba ABW Aruba United States of America USA US-ID Idaho Australia AUS Australia United States of America USA US-IL Illinois Austria AUT Austria United States of America USA US-IN Indiana Azerbaijan AZE Azerbaijan United States of America USA US-IA Iowa Bahamas BHS Bahamas United States of America USA US-KS Kansas Bahrain BHR Bahrain United States of America USA US-KY Kentucky Bangladesh BGD Bangladesh United States of America USA US-LA Louisiana Barbados -

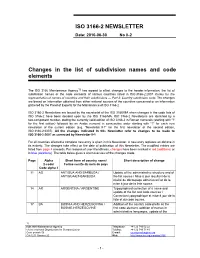

ISO 3166-2 NEWSLETTER Changes in the List of Subdivision Names And

ISO 3166-2 NEWSLETTER Date: 2010-06-30 No II-2 Changes in the list of subdivision names and code elements The ISO 3166 Maintenance Agency1) has agreed to effect changes to the header information, the list of subdivision names or the code elements of various countries listed in ISO 3166-2:2007 Codes for the representation of names of countries and their subdivisions — Part 2: Country subdivision code. The changes are based on information obtained from either national sources of the countries concerned or on information gathered by the Panel of Experts for the Maintenance of ISO 3166-2. ISO 3166-2 Newsletters are issued by the secretariat of the ISO 3166/MA when changes in the code lists of ISO 3166-2 have been decided upon by the ISO 3166/MA. ISO 3166-2 Newsletters are identified by a two-component number, stating the currently valid edition of ISO 3166-2 in Roman numerals (starting with "I" for the first edition) followed by an Arabic numeral in consecutive order starting with "1" for each new newsletter of the current edition (e.g. "Newsletter II-1" for the first newsletter of the second edition, ISO 3166-2:2007). All the changes indicated in this Newsletter refer to changes to be made to ISO 3166-2:2007 as corrected by Newsletter II-1. For all countries affected a complete new entry is given in this Newsletter. A new entry replaces an old one in its entirety. The changes take effect on the date of publication of this Newsletter. The modified entries are listed from page 4 onwards. -

Country Codes in ISO 3166 Page 1 of 10 Country Codes in ISO 3166

Country codes in ISO 3166 Page 1 of 10 Country codes in ISO 3166 Page last modified: 2003-07-25 Data last modified: 2003-07-25 This file lists the codes for each country provided in ISO 3166. There are two tables: existing codes and withdrawn codes (codes can be withdrawn because the country no longer exists, the name has significantly changed, or one or more codes has altered). Each country or territory has three codes: l a two letter code l a three letter code l a three digit code The numeric code identifies a physical territory, and the letters a country name. Thus when Germany reunified, it kept DE/DEU but changed from 280 to 276, while when Southern Rhodesia was renamed Zimbabwe it stayed 716 but changed from RH/RHO to ZW/ZWE. There is also a numeric version of the two letter code not given here, calculated as 1070+30a+b, where a and b are the two letters of the code converted by A=1, B=2, etc. So AA=1101, AB=1102, BA=1131, and ZZ=1876. Changes to ISO 3166 are managed by the ISO 3166 Maintenance Agency (ISO3166/MA). Codes withdrawn from use may not be reused for five years. The two letter codes AA, QM to QZ, XA to XZ, and ZZ, all three letter codes beginning with those pairs, and numeric codes beginning 9, are available for individual use and will not be allocated to countries. The codes OO, OOO, and 000 are designated for use as "escape codes" to indicate that additional codes are being used. -

Initiation Plan

United Nations Development Programme Country/Region/Global: INDONESIA Initiation Plan Project Title: Archipelagic and Island States Forum Support Facility Expected UNDAF/CP Outcome(s): 3. By 2020, Indonesia is sustainably managing its natural resources, on land and at sea, with an increased resilience to the effects of climate change, disasters and other shocks Expected CPD Output(s): 3.8. Policy and Technical Guidance are in place for integrating climate change adaptation (CCA) and DRR into spatial and local development planning Initiation Plan Start/End Dates: September 1, 2019 to December 30 2019 Implementing Partner: UNDP Indonesia Brief Description This project aims to establish the Archipelagic and Island States (AIS) Forum’s Support Facility(“AISF-SF”), ensure its ability to operate effectively and also ensure effective implementation and achievement of its key services. Serving stakeholders from all over the world, the AISF-SF will be responsible for directing the Forum’s program of events, managing the AIS Fund Facility and other finances, maintaining relationships with Participants, and develop stakeholder networks. Throughout the project, gender mainstreaming considerations will be incorporated in all aspects of the project. During this PIP periode, the AIS Forum Project Document will be finalized and signed by relevant parties for implementation in until December 2021. Programme Period: 2019-2021 Total resources required USD 196.639* Total allocated resources: USD 196.639 Atlas Project ID: 00115025 Regular (UNDP) 0 Gov’t of Indonesia USD 196.639 Atlas Output ID: 00112805 Gender Marker: GEN 2 Unfunded budget: 0 In-kind Contributions 0 *Note: the Government of Indonesia will transfer the funds in IDR currency amounting IDR 2.786.966.800. -

Law of the Sea and the Svalbard Islands: an Analysis on the Legal Status of Maritime Zones Around Svalbard

Law of the Sea and the Svalbard Islands: An analysis on the legal status of maritime zones around Svalbard Irina Ivanova Anr: 911311 Tilburg University LLM International and European Law Master of Laws Thesis Submitted: August 2018 Supervisor: Dr Morag Goodwin Acknowledgements First and foremost, I am especially grateful to Dr Morag Goodwin, for her supervision, useful comments and valuable insights throughout my research. Many thanks to my study colleagues in Tilburg Law School, for interesting discussions and meaningful friendships. To mama, I owe everything. Thank you for inspiring and helping with this thesis, continuously listening to my legal nonsense and always answering my calls when I needed you. You always gave me the liberty to follow my interests and encouraged me every step of the way, Thank you for being my ultimate role model. My girls, you’ve supported me during the writing process by making me laugh and being the necessary distraction. I couldn’t have done it without our ‘perfect club’. Always grateful to my Strasbourg friends, for bouncing ideas with me and despite the time and the distance, being there. And lastly, I would like to thank the Verschoor family, for welcoming me and making this foreign country my home. ii Contents Acknowledgements ..................................................................................................................................... i Abbreviations ......................................................................................................................................... -

Downloaded Electronically, Or Where There Are No Customs Operations at Borders

International Tax Policy Forum and Georgetown Law’s Institute of International Economic Law Tax Competition February 3, 2017 Georgetown University Law Center 120 F Street NW Washington, D.C. 20001 ITPF & IIEL Conference Tax Competition February 3, 2017 Table of Contents Page I. PROGRAM AGENDA ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. ABOUT THE INTERNATIONAL TAX POLICY FORUM ................................................................. 5 III. ABOUT THE INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL ECONOMIC LAW .............................................. 6 IV. PAPERS A. R. Davies, I. Siedschlas, Z. Studnicka “The Impact of Taxes on the Extensive and Intensive Margins of FDI” July 2016 .......................................................................................................... 8 B. R. Davies, R. Desbordes, A. Ray “Greenfield versus Merger & Acquisition FDI: Same Wine, Difference Bottles?” September 2015 ............................................................................ 52 C. A. Auerbach, M. Devereux, M. Keen, J. Vella “Destination-Based Cash Flow Taxation” January 2017 ........................................................................................................................... 94 D. R. Avi-Yonah, K. Clausing “Problems with Destination-Based Corporate Taxes and the Ryan Blueprint” January 2017 .......................................................................................... 192 E. K. Clausing “The Effect of Profit Shifting on -

Free One Small Island Pdf

FREE ONE SMALL ISLAND PDF Alison Lester,Coral Tulloch | 32 pages | 01 Aug 2011 | Penguin Books Australia | 9780670072361 | English | Hawthorn, Australia One Small Island by Alison Lester The hard-nosed, hard-working, democratic, devout population of 2. The relatively small, corrupt government juggles the competing demands of Education, Industry, and Administration. It meets to discuss matters of state in the capital city of Darkwater. The average One Small Island tax rate is 8. The frighteningly efficient Islandian economy, worth trillion Sand Dollars a year, One Small Island quite specialized and led by the Gambling industry, with major contributions from Soda Sales, Retail, and Arms Manufacturing. Black market activity is rampant. Average income is an impressiveSand Dollars, and evenly distributed, with the richest citizens earning only 4. The standardised national curriculum requires that all-male classes be taught why they have periods, airport security is provided by private companies, international collectors know that a grease-stain on a work of art probably means it's passed through One Small Island, and anti-vaxxers are right about the government injecting diseases into people. Crime, especially youth-related, is all-pervasive, perhaps because of the country's complete lack of prisons. One Small Island's national animal is the Seagull, which is also the nation's favorite main course, and its national religion is Piracy. View Forum posts Report. WA Delegate. One Small Island. Be as the sea. Always in motion. Stillness is death. Kalani T'ai. Warzone Sandbox. Civil Rights. One Small Island Population 2. The Tropical Paradise of One Small Island is a massive, cultured One Small Island, ruled by Kalani T'ai with an even hand, and notable for its keen interest in outer space, One Small Island dinosaurs, and multi-spousal wedding ceremonies. -

Rural Push, Urban Pull And... Urban Push? New Historical Evidence

Rural Push, Urban Pull and... Urban Push? New Historical Evidence from Developing Countries∗ Remi Jedwab† and Luc Christiaensen‡ and Marina Gindelsky§ January 2014 Abstract: Standard models explain urbanization by rural-urban migration in response to an (expected) urban-rural wage gap. The Green Revolution and rural poverty constitute rural push factors of migration. The Indus- trial Revolution and the urban bias are urban pull factors. This paper offers an additional demographic mechanism, based on internal urban population growth, i.e. an urban push. Using newly compiled historical data on urban birth and death rates for 7 countries from Industrial Europe (1800-1910) and 33 developing countries (1960-2010), we show that many cities of to- day’s developing world are “mushroom cities” vs. the “killer cities” of In- dustrial Europe; fertility is high, while mortality is much lower. The high rates of urban natural increase have then accelerated urban growth and ur- banization in developing countries, with urban populations now doubling every 18 years (15 years in Africa), compared to every 35 years in Industrial Europe. This is further found to be associated with higher urban congestion, possibly mitigating the benefits from agglomeration and providing further insights into the phenomenon of urbanization without growth. Both migra- tion and urban demographics must be considered in debating urbanization. Keywords: Urbanization; Demographic Transition; Migration; Poverty; Slums JEL classification: O1; O18; R11; R23; J11; ∗We would like to thank -

National Code of Countries and Nationalities

National Code of Countries and Nationalities According to the (Country Codes – ISO 3166) February 2017 Codes and Classifications Codes & Classifications National Code of Countries & Nationalities Introduction The code of countries and nationalities is a world-standardized classification for countries that is set as per the Country Codes ISO 3166 issued by the International Organization for Standardization, another United Nations standard-setting body, which makes the list that defines codes for the names of countries, provinces and states. The code is the language of numbers that saves time and avoids mistakes when using names of the countries for statistical purposes. For example, numbers set on passports can be understood by everyone to refer for nationalities and names of countries. Countries and nationalities were divided into the following groups: • Countries by group are (the GCC countries, other Arab League countries, non-Arab Islamic countries, non-Arab non-Islamic Asian countries, non-Arab non-Islamic African countries, EU countries, European non-EU member states, North American countries, South American countries, Oceania countries and others) • Nationalities by group are (nationalities of the GCC countries, other Arab League countries, non-Arab Islamic countries, non-Arab non-Islamic Asian countries, non-Arab non-Islamic African countries, EU countries, European non-EU member states, North American countries, South American countries, Oceania countries and others) The Saudi code is divided into three sections: • Alpha-2: A two-letter code that stands for names of the countries. It is common on internet for referring to country codes. • Alpha-3: A three-letter code that stands for the official name of a country which is clearer than the two-letter codes. -

Greenfield Versus Merger & Acquisition

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Davies, Ronald B.; Desbordes, Rodolphe; Ray, Anna Working Paper Greenfield versus merger & acquisition FDI: Same wine, different bottles? UCD Centre for Economic Research Working Paper Series, No. WP15/03 Provided in Cooperation with: UCD School of Economics, University College Dublin (UCD) Suggested Citation: Davies, Ronald B.; Desbordes, Rodolphe; Ray, Anna (2015) : Greenfield versus merger & acquisition FDI: Same wine, different bottles?, UCD Centre for Economic Research Working Paper Series, No. WP15/03, University College Dublin, UCD School of Economics, Dublin This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/109729 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents -

Mobile Money, Rural Household Welfare and Remittances: Panel Evidence from Uganda

Mobile Money, Rural Household Welfare and Remittances: Panel Evidence from Uganda Ggombe Kasim Munyegera ƒ and Tomoya Matsumoto ℘ February 2014 Abstract Mobile money service in Uganda has expanded rapidly, penetrating as much as over 30 percent of the adult population in just four years since its inception. We investigate the impact of this financial innovation on household welfare, using household survey panel data from rural Uganda. Results from our preferred specification reveal that adopting mobile money services increases household per capita consumption by 69 percent. The mechanism of this impact is the facilitation of remittances; user households are more likely to receive remittances, receive remittances more frequently and the total value received is significantly higher than that of non-user households. Our results are robust to a number of robustness checks. Key words: Mobile money, financial inclusion, household welfare. JEL Classification: O16, O17, O33, I131 ƒ Corresponding author. National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies. 7-22-1 Roppongi, Minato-ku 106- 8677 Tokyo Japan. Contact: [email protected] ℘ National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies. 7-22-1 Roppongi, Minato-ku 106-8677 Tokyo Japan. 1 I. Introduction Financial inclusion 1 plays an integral role in reducing rural poverty as it facilitates saving and borrowing as well as empowering the poor to smooth consumption and insure themselves against a number of vulnerabilities in their lives (World Bank, 2012). However, a large fraction of the population in developing countries lacks access to the basic financial services (Asli and Klapper, 2012). Lack of access to basic financial services restricts the ability of the rural poor to make savings and investments and engage in both formal and informal insurance mechanisms aimed at smoothing consumption and curbing poverty (Dupas and Robinson, 2008).