Urbanization with and Without Industrialization∗

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Poverty of Cities in Developing Regions

The Poverty of Cities in Developing Regions MARTIN BROCKERHOFF ELLEN BRENNAN A LONG-STANDING BELIEF in development studies holds that, on the whole, living conditions in developing countries are superior for residents of large cities than for persons living in smaller cities, towns, and villages. The con- cept of big cities as “islands of privilege” (Harrison 1982: 145) is funda- mental to otherwise discrepant theories of modernization, dependency, world systems of cities, and the global division of labor, each of which pos- its long-lasting disadvantages for populations outside of major urban cen- ters.1 It is also supported by evidence from numerous developing countries of lower child mortality rates, greater income-earning opportunities, less fre- quent and less severe famines, and better access to publicly conferred entitle- ments in big cities than in smaller areas in the era since World War II. Since the late 1980s, however, the presumed superiority of large cit- ies in developing countries has been widely disputed. One argument, in- formed by evidence of rapid population growth and economic stagnation in many cities, and by perceptions of associated negative externalities im- posed on city environments, asserts deteriorating or relatively unfavorable living conditions for big-city residents, on average, as compared with con- ditions for inhabitants of smaller cities and towns. Paul Kennedy (1993: 26) observes that “Asian, Latin American, and Central American mega- cities of 20 million inhabitants have become increasingly centers of pov- erty and social collapse.”2 The International Labour Organization reports that by around 1990, most residents of Bombay, Cairo, and Lagos were living in slums (Oberai 1993: 8). -

Paper-20 Urban Sociology

MA SOCIOLOGY P-20 URBAN SOCIOLOGY Author Dr. P.K.Kar 1 Unit-I: Evolution of Cities in History based on Major Functions:Growth of Urbanization in India, City type and functions in India, The Rural-Urban dichotomy and continum in India and Theories of Unrbanization Unit-II:Social Institutions in the Urban Milieu:Family and Marriage Caste, Religion, Economy, Polity Unit-III: The new Social Structures in Urban India:Informal Sector: Various Occupations , Formal Sector: Various Professions and Secondary Institutions: Educational, Leisure and Recreation, Voluntary Organizations. Unit-IV: Problems of Urban India: Housing, Transport, Communication, Pollution, Sanitation, And Crime. UNIT-I Evolution of Cities in History based on Major Functions: CONTENTS 1.0. OBJECTIVES 1.1. EVOLUTION OF CITIES IN HISTORY BASED ON FUCTIONS 1.1.1 Ancient Cities 1.1.2 Medieval cities 1.1.3 Modern Cities 1.1.4 Pre-lndustrial Cities 1.1.5 Industrial Cities 1.2. GROWTH OF URBANIZATION IN INDIA 1.3. REGIONAL URBANISATION PROCESS: 1.4. FORMATION OF URBAN AGGLOMERATION 2 1.5. TRENDS AND PATTERNS OF URBANIZATION IN INDIA 1.5.1 Demographic approach 1.5.2 Geographic approach 1.6. URBAN ECONOMIC GROWTH 1.6.1. Size of total NDP by sectors and per capita NDP 1.7. COMPOUND ANNUAL GROWTH 1.8. CITY TYPE AND FUCTIONS IN INDIA 1.9. RURAL URBAN DICHOTOMY AND CONTINUUM 1.10. DISTINCTION BETWEEN RURAL AND URBAN COMMUNITIES 1.11. THEORIES OF URBAN GROWTH 1.11.1. Concentric zone model 1.11.2. Sectors model 1.11.3. Multiple nuclei model 1.11.4. -

Urbanization, Urban Concentration and Growth

CORE DISCUSSION PAPER 2003/76 Urbanization, Urban Concentration and Economic Growth in Developing Countries Luisito BERTINELLI1 and Eric STROBL2 October 2003 Abstract We investigate how urban concentration and urbanization affect economic growth in developing countries. Using semi-parametric estimation techniques on a cross-country panel of 39 countries for the years 1960-1990 we discover a U-shaped relationship for urban concentration. This suggests the existence of an urban-concentration trap where marginal increases in urban concentration would reduce growth for about a third of our sample. Furthermore, there appears to be no systematic relationship between urbanization and economic growth. Keywords: urban concentration, economic development, LDCs, semiparametric estimations JEL classification: R11, O18, C14 1Université du Luxembourg, 162A avenue de la Faïencerie 1511 Luxembourg, and CORE, 34 Voie du Roman Pays 1348 Louvain-La-Neuve, Belgium. E-mail: [email protected]. 2CORE, 34 Voie du Roman Pays 1348 Louvain-La-Neuve, Belgium. E-mail: [email protected]. Financial support from a European Commission Marie Curie Fellowship is gratefully acknowledged. Both authors are grateful to James Davis and Vernon Henderson for making their data available. Section I: Introduction It has been argued that strong urban economies are the backbone and motor of the wealth of nations (Jacobs (1984)). As countries become more reliant on manufacturing and services and less on agriculture, urban areas are more likley to become important for fostering marshallian externalities, nourishing innovation, providing a hub for trade, and encouraging human capital accumulation. Such economies should be particularly important for developing countries since trends in urbanization show that the share of the urban population has increased substantially in these since the 1950s. -

Global and National Sources of Political Protest: Third World Responses to the Debt Crisis*

GLOBAL AND NATIONAL SOURCES OF POLITICAL PROTEST: THIRD WORLD RESPONSES TO THE DEBT CRISIS* JoHN WALTON CHARLES RAGIN University of California -Davis Northwestern University In recent years international financial institutions have required Third World debtor coun tries to adopt various austerity policies designed to restore economic viability and ensure debt repayment. The hardships created by these policies have provoked unprecedented protests in debtor countries, ranging from mass demonstrations to organized strikes and riots. We examine variation among Third World debtor countries in the presence and severity ofprotests against austerity policies. Results show that the principal conditions for the occurrence and severity of austerity p~otests are overurbanization and involvement of international agencies in domestic political-economic policy. We offer a theoretical inter pretation that integrates global and national sources ofcontemporary political protest in the Third World. or more than a decade, the international debt private banks rose from one-third to over one F crisis has provoked a wave of mass protests half (Moffitt 1983). against austerity policies imposed on the devel From the mid-1970s on, a few smaller countries oping countries. These protests are rooted in the (e.g:, Peru and Jamaica) began experiencing se global political economy, not in the singular di vere balance of payment problems and threat lemmas of Third World countries. With the pos ened bankruptcy. However, the international debt sible exception of the European revolutions of crisis was not widely recognized as such until 1848, these protests constitute an unprecedented 1982 when Mexico announced the exhaustion of wave of international protest. They provide a its foreign exchange reserves. -

Demography, Urbanization and Development

WPS7333 Policy Research Working Paper 7333 Public Disclosure Authorized Demography, Urbanization and Development Rural Push, Urban Pull and … Urban Push? Public Disclosure Authorized Remi Jedwab Luc Christiaensen Marina Gindelsky Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Africa Region Office of the Chief Economist June 2015 Policy Research Working Paper 7333 Abstract Developing countries have urbanized rapidly since 1950. rapid urban growth and urbanization may also be linked To explain urbanization, standard models emphasize rural- to demographic factors, such as rapid internal urban urban migration, focusing on rural push factors (agricultural population growth, or an urban push. High urban natu- modernization and rural poverty) and urban pull factors ral increase in today’s developing countries follows from (industrialization and urban-biased policies). Using new lower urban mortality, relative to Industrial Europe, where historical data on urban birth and death rates for seven higher urban deaths offset urban births. This compounds countries from Industrial Europe (1800–1910) and the effects of migration and displays strong associations thirty-five developing countries (1960–2010), this paper with urban congestion, providing additional insight argues that a non-negligible part of developing countries’ into the phenomenon of urbanization without growth. This paper is a product of the Office of the Chief Economist, Africa Region of the World Bank, in collaboration with George Washington University. It is part of a larger effort by the World Bank to provide open access to its research and make a contribution to development policy discussions around the world. Policy Research Working Papers are also posted on the Web at http://econ.worldbank.org. -

Protestant Ethic and the Not-So-Sociology of World Religions

Bangladesh e-Journal of Sociology. Volume 1. Number 1. January 2004. 52 Protestant Ethic and the Not-So-Sociology of World Religions - Nazrul Islam * Probably the most talked about sociologist, definitely the most influential of them all, Max Weber, is known for many great works. He is known most for his analysis of the Protestant ethic, as for his theory of action, for his political sociology, sociology of music and his sociology of religion. But his lifetime work seems to be in the area of what has come to be known as the “world religions”. He undertook the colossal project of making sense of the major religions of the world but left it incomplete as his life was, unfortunately, shortened. Yet, what he achieved in that short life is the envy of most scholars, definitely of all sociologists. Like most sociologists I have unbounded appreciation for the amount he achieved but unlike most sociologists I fail to see much sociology in his work, particularly in his study of the world religions. In this paper I shall focus on his seminal work on the Protestant ethic and the other world religions and try to show why these are not so sociological . The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (2003a) seems to have launched Weber into a life long quest for unraveling the secret that religions held in terms of their hitherto unheard of influence on economics. For much of history and for most religions economics or the mundane pursuit of life is beyond the sphere of godly virtues. Poverty and asceticism are the most virtuous quality for the faithful and the key to unending happiness in the world beyond. -

Urbanization with and Without Industrialization∗

Urbanization with and without Industrialization∗ a Douglas GOLLIN Rémi JEDWABb Dietrich VOLLRATHc a Department of International Development, University of Oxford b Department of Economics, George Washington University c Department of Economics, University of Houston This Version: October 1st, 2013 Abstract: Many theories link urbanization with industrialization; in partic- ular, with the production of tradable (and typically manufactured) goods. We document that the expected relationship between urbanization and the level of industrialization is not present in a sample of developing economies. The breakdown occurs due to a large sub-sample of resource exporters that have urbanized without increasing output in either manufacturing or in- dustrial services such as finance. To account for these stylized facts, we construct a model of structural change that accommodates two different paths to high urbanization rates. The first involves the typical movement of labor from agriculture into industry, as in many models of structural change; this stylized pattern leads to what we term “production cities” that produce tradable goods. The second path is driven by the income effect of natural resource endowments: resource rents are spent on urban goods and services, which gives rise to “consumption cities” that are made up pri- marily of workers in non-tradable services. We document empirically that there is such a distinction in the employment composition of cities between developing countries that rely on natural resource exports and those that do not. Our model and the supporting data suggest that urbanization is not a homogenous event, and this has possible implications for long-run growth. Keywords: Structural Change; Urbanization; Industrialization JEL classification: L16; N10; N90; O18; O41; R10 ∗Douglas Gollin, University of Oxford (e-mail: [email protected]). -

DPCC Country Codes V1.2 (PDF)

DPCC Country Codes List v1.2 DPCC Country Codes List v1.2 - ISO 3166 Standard DPCC State Province Codes List v1.2 - ISO 3166-2 Standard ISO Country Name ISO Country Code NCBI Country Name ISO Country Name ISO Country Code ISO State Province Code ISO State Province Name Afghanistan AFG Afghanistan United States of America USA US-AL Alabama Aland Islands ALA United States of America USA US-AK Alaska Albania ALB Albania United States of America USA US-AZ Arizona Algeria DZA Algeria United States of America USA US-AR Arkansas American Samoa ASM American Samoa United States of America USA US-CA California Andorra AND Andorra United States of America USA US-CO Colorado Angola AGO Angola United States of America USA US-CT Connecticut Anguilla AIA Anguilla United States of America USA US-DE Delaware Antarctica ATA Antarctica United States of America USA US-DC District of Columbia Antigua and Barbuda ATG Antigua and Barbuda United States of America USA US-FL Florida Argentina ARG Argentina United States of America USA US-GA Georgia Armenia ARM Armenia United States of America USA US-HI Hawaii Aruba ABW Aruba United States of America USA US-ID Idaho Australia AUS Australia United States of America USA US-IL Illinois Austria AUT Austria United States of America USA US-IN Indiana Azerbaijan AZE Azerbaijan United States of America USA US-IA Iowa Bahamas BHS Bahamas United States of America USA US-KS Kansas Bahrain BHR Bahrain United States of America USA US-KY Kentucky Bangladesh BGD Bangladesh United States of America USA US-LA Louisiana Barbados -

Urbanization in the People's Republic of China: Continuity and Change

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1989 Urbanization in the People's Republic of China: Continuity and Change Jing Zhang Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Zhang, Jing, "Urbanization in the People's Republic of China: Continuity and Change" (1989). Master's Theses. 3611. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/3611 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1989 Jing Zhang I URBANIZATION IN THE PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC OF CHINA: CONTINUITY AND CHANGE By Jing Zhang A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Loyola Un~versity of Chicago In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts September 1989 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my thesis committee, Dr. Kathleen I Mccourt, Dr. Richard Block and Dr. Philip Nyden, for their patient help and guidance in my writing this thesis. I would like to thank Lauree Garvin who helped correct my faulty English. All the shortcomings will be my responsibility. I am indebted to Dr. Kirsten Gronbjerg, Dr. Kenneth Johnson, Dr. Marilyn Fernandez, and Dr. David Fasenfast for their encouragement and suggestions at different stages. I am also grateful to the Department of Sociology and Anthropology and the Graduate School at Loyola University of Chicago for their financial support in my graduate study. -

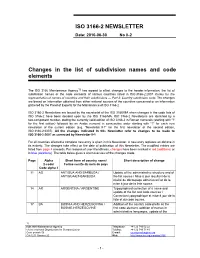

ISO 3166-2 NEWSLETTER Changes in the List of Subdivision Names And

ISO 3166-2 NEWSLETTER Date: 2010-06-30 No II-2 Changes in the list of subdivision names and code elements The ISO 3166 Maintenance Agency1) has agreed to effect changes to the header information, the list of subdivision names or the code elements of various countries listed in ISO 3166-2:2007 Codes for the representation of names of countries and their subdivisions — Part 2: Country subdivision code. The changes are based on information obtained from either national sources of the countries concerned or on information gathered by the Panel of Experts for the Maintenance of ISO 3166-2. ISO 3166-2 Newsletters are issued by the secretariat of the ISO 3166/MA when changes in the code lists of ISO 3166-2 have been decided upon by the ISO 3166/MA. ISO 3166-2 Newsletters are identified by a two-component number, stating the currently valid edition of ISO 3166-2 in Roman numerals (starting with "I" for the first edition) followed by an Arabic numeral in consecutive order starting with "1" for each new newsletter of the current edition (e.g. "Newsletter II-1" for the first newsletter of the second edition, ISO 3166-2:2007). All the changes indicated in this Newsletter refer to changes to be made to ISO 3166-2:2007 as corrected by Newsletter II-1. For all countries affected a complete new entry is given in this Newsletter. A new entry replaces an old one in its entirety. The changes take effect on the date of publication of this Newsletter. The modified entries are listed from page 4 onwards. -

Country Codes in ISO 3166 Page 1 of 10 Country Codes in ISO 3166

Country codes in ISO 3166 Page 1 of 10 Country codes in ISO 3166 Page last modified: 2003-07-25 Data last modified: 2003-07-25 This file lists the codes for each country provided in ISO 3166. There are two tables: existing codes and withdrawn codes (codes can be withdrawn because the country no longer exists, the name has significantly changed, or one or more codes has altered). Each country or territory has three codes: l a two letter code l a three letter code l a three digit code The numeric code identifies a physical territory, and the letters a country name. Thus when Germany reunified, it kept DE/DEU but changed from 280 to 276, while when Southern Rhodesia was renamed Zimbabwe it stayed 716 but changed from RH/RHO to ZW/ZWE. There is also a numeric version of the two letter code not given here, calculated as 1070+30a+b, where a and b are the two letters of the code converted by A=1, B=2, etc. So AA=1101, AB=1102, BA=1131, and ZZ=1876. Changes to ISO 3166 are managed by the ISO 3166 Maintenance Agency (ISO3166/MA). Codes withdrawn from use may not be reused for five years. The two letter codes AA, QM to QZ, XA to XZ, and ZZ, all three letter codes beginning with those pairs, and numeric codes beginning 9, are available for individual use and will not be allocated to countries. The codes OO, OOO, and 000 are designated for use as "escape codes" to indicate that additional codes are being used. -

Debt, Structural Adjustment, and Non-Governmental Organizations: a Cross-National Analysis of Maternal Mortality

DEBT, STRUCTURAL ADJUSTMENT, AND NON-GOVERNMENTAL ORGANIZATIONS: A CROSS-NATIONAL ANALYSIS OF MATERNAL MORTALITY John M. Shandra Department of Sociology State University of New York at Stony Brook [email protected] Carrie L. Shandra Department of Sociology Hofstra University [email protected] Bruce London Department of Sociology Clark University [email protected] ABSTRACT We begin this study by considering dependency theory claims regarding the harmful influence of both debt and structural adjustment on maternal mortality. We expand upon previous research by conducting the first cross-national study to examine the impact of health and women’s non-governmental organizations on maternal mortality. In doing so, we use lagged dependent variable panel regression for a sample of sixty-five poor nations. We find substantial support for dependency theory that higher levels of debt service, structural adjustment, and multinational corporate investment are associated with increased maternal mortality. Initially, we find no support for world polity theory that health and women’s non-governmental organizations are significantly related to maternal mortality. However, we respecify our original models in order to test the idea that democratic nations provide a "political opportunity structure" that improves the ability of health and women’s non-governmental organizations to deliver health and other social services. We find substantial support for this hypothesis. The results indicate that both health and women’s non-governmental organizations are associated with decreased maternal mortality in nations with higher levels of democracy than in nations with lower levels of democracy. We conclude with a discussion of the findings, theoretical implications, methodological implications, policy implications, and potential directions for future research.