Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Genetic Markers in Lung Cancer Diagnosis: a Review

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review Genetic Markers in Lung Cancer Diagnosis: A Review Katarzyna Wadowska 1 , Iwona Bil-Lula 1 , Łukasz Trembecki 2,3 and Mariola Sliwi´ ´nska-Mosso´n 1,* 1 Department of Medical Laboratory Diagnostics, Division of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Haematology, Wroclaw Medical University, 50-556 Wroclaw, Poland; [email protected] (K.W.); [email protected] (I.B.-L.) 2 Department of Radiation Oncology, Lower Silesian Oncology Center, 53-413 Wroclaw, Poland; [email protected] 3 Department of Oncology, Faculty of Medicine, Wroclaw Medical University, 53-413 Wroclaw, Poland * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +48-71-784-06-30 Received: 1 June 2020; Accepted: 25 June 2020; Published: 27 June 2020 Abstract: Lung cancer is the most often diagnosed cancer in the world and the most frequent cause of cancer death. The prognosis for lung cancer is relatively poor and 75% of patients are diagnosed at its advanced stage. The currently used diagnostic tools are not sensitive enough and do not enable diagnosis at the early stage of the disease. Therefore, searching for new methods of early and accurate diagnosis of lung cancer is crucial for its effective treatment. Lung cancer is the result of multistage carcinogenesis with gradually increasing genetic and epigenetic changes. Screening for the characteristic genetic markers could enable the diagnosis of lung cancer at its early stage. The aim of this review was the summarization of both the preclinical and clinical approaches in the genetic diagnostics of lung cancer. The advancement of molecular strategies and analytic platforms makes it possible to analyze the genome changes leading to cancer development—i.e., the potential biomarkers of lung cancer. -

Invasive Cervical Cancer Audit; EU Guidelines for Quality Assurance

The 4th EFCS Annual Tutorial Ospedale Universitario di Cattinara, Strada di Fiume, Trieste Handouts for lectures and workshops – I I - Gynaecological cytopathology Mrs Rietje Salet‐van‐de Pol, Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Centre, Nijmegen, The Netherlands Gynecological cytology: technical aspects ............................................................................... 2 Non‐neoplastic gynecological cytology .................................................................................... 6 • Dr Giovanni Negri, General Hospital of Bolzano, Bozano SIL and cancer; ASC‐US, ASC‐H, diagnostic pitfalls and look‐alikes; glandular abnormalities 11 • Dr Amanda Herbert, Guy’s & St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, London Invasive cervical cancer audit; EU guidelines for quality assurance ...................................... 17 1 Gynecological cytology: technical aspects Rietje Salet-van de Pol Important in specimen processing is to obtain as much as possible well preserved cells for microscopically evaluation. The quality of the smear depends on cell sampling, fixation and staining. For obtaining enough cervical material you are dependent on the cell sampler. For cervical cytology two types of specimen are available: conventional smears and liquid based cytology (LBC). Conventional, Thinprep and Surepath slides In conventional cytology the cell sampler makes the smear and is responsible for the fixation of the cells. Reasons for unsatisfactory conventional smears can be obscuring blood or inflammatory cells, thick smears with overlapping cells, poor preservation of the cells due to late fixation and low cellularity. In LBC the cell sampler immediately transferred the cellular material into a vial with fixative (fixating solution) which gives a better preservation of the cells. The laboratory is responsible for processing of the smear. LBC gives equally distribution of the cells in a thin cell layer of well preserved cells. The rate of unsatisfactory smears is lower. -

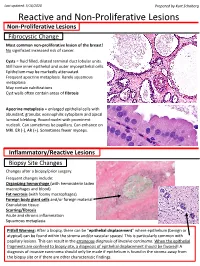

Reactive and Non-Proliferative Lesions

Last updated: 5/16/2020 Prepared by Kurt Schaberg Reactive and Non-Proliferative Lesions Non-Proliferative Lesions Fibrocystic Change Most common non-proliferative lesion of the breast! No significant increased risk of cancer. Cysts = fluid filled, dilated terminal duct lobular units. Still have inner epithelial and outer myoepithelial cells. Epithelium may be markedly attenuated. Frequent apocrine metaplasia. Rarely squamous metaplasia May contain calcifications Cyst walls often contain areas of fibrosis Apocrine metaplasia = enlarged epithelial cells with abundant, granular, eosinophilic cytoplasm and apical luminal blebbing. Round nuclei with prominent nucleoli. Can sometimes be papillary. Can enhance on MRI. ER (-), AR (+). Sometimes fewer myoeps. Inflammatory/Reactive Lesions Biopsy Site Changes Changes after a biopsy/prior surgery. Frequent changes include: Organizing hemorrhage (with hemosiderin laden macrophages and blood) Fat necrosis (with foamy macrophages) Foreign body giant cells and/or foreign material Granulation tissue Scarring/fibrosis Acute and chronic inflammation Squamous metaplasia Pitfall Warning: After a biopsy, there can be “epithelial displacement” where epithelium (benign or atypical) can be found within the stroma and/or vascular spaces! This is particularly common with papillary lesions. This can result in the erroneous diagnosis of invasive carcinoma. When the epithelial fragments are confined to biopsy site, a diagnosis of epithelial displacement should be favored! A diagnosis of invasive carcinoma should -

Primary Immature Teratoma of the Thigh Fig

CORRESPONDENCE 755 8. Gray W, Kocjan G. Diagnostic Cytopathology. 2nd ed. London: Delete all that do not apply: Elsevier Health Sciences, 2003; 677. 9. Richards A, Dalrymple C. Abnormal cervicovaginal cytology, unsatis- Cervix, colposcopic biopsy/LLETZ/cone biopsy: factory colposcopy and the use of vaginal estrogen cream: an obser- vational study of clinical outcomes for women in low estrogen states. Diagnosis: NIL (No intraepithelial lesion WHO 2014) J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2015; 41: 440e4. LSIL (CIN 1 with HPV effect WHO 2014) 10. Darragh TM, Colgan TJ, Cox T, et al. The lower anogenital squamous HSIL (CIN2/3 WHO 2014) terminology standardization project for HPV-associated lesions: back- Squamous cell carcinoma ground and consensus recommendation from the College of American Immature squamous metaplasia Pathologists and the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS, HGGA) e Adenocarcinoma Pathology. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2012; 136: 1267 97. Atrophic change 11. McCluggage WG. Endocervical glandular lesions: controversial aspects e Extending into crypts: Not / Idenfied and ancillary techniques. J Clin Pathol 2013; 56: 164 73. Epithelial stripping: Not / Present 12. World Health Organization (WHO). Comprehensive Cervical Cancer Invasive disease: Not / Idenfied / Micro-invasive Control: A Guide to Essential Practice. 2nd ed. Geneva: WHO, 2014. Depth of invasion: mm Transformaon zone: Not / Represented Margins: DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pathol.2019.07.014 Ectocervical: Not / Clear Endocervical: Not / Clear Circumferenal: Not / Clear p16 status: Negave / Posive Primary immature teratoma of the thigh Fig. 3 A proposed synoptic reporting format for pathologists reporting colposcopic biopsies and cone biopsies or LLETZ. Sir, Teratomas are germ cell tumours composed of a variety of HSIL, AIS, micro-invasive or more advanced invasive dis- somatic tissues derived from more than one germ layer 12 ease. -

Non-Hodgkin's Gastrointestinal Lymphoma Presenting As Acute

Cirujano CLINICAL CASE General July-September 2019 Vol. 41, no. 3 / p. 208-216 Non-Hodgkin’s gastrointestinal lymphoma presenting as acute abdomen Linfoma no Hodgkin gastrointestinal presentándose como abdomen agudo CLINICAL CASES Arcenio Luis Vargas-Ávila,* Alan Hernández-Rosas,** José Roldán-Tinoco,*** Levi Alan Guzmán-Peña,*** Julián Vargas-Flores,**** Julio Adán Campos-Badillo,*** CASOS CLÍNICOS Rubén Mena-Maldonado***** Keywords: Lymphoma, small ABSTRACT RESUMEN intestine, hemorrhage, acute abdomen. Non-Hodgkin lymphoma is an uncommon cancer, but El linfoma no Hodgkin es una neoplasia poco común, when it is a primary lymphoma, the gastrointestinal tract pero cuando se trata de un linfoma primario, el tracto Palabras clave: is the most commonly involved and one of the most gastrointestinal es el sitio más comúnmente implicado y Linfoma, intestino common extra-nodal sites. Multiple risk factors have una de las presentaciones extranodales más frecuentes. delgado, hemorragia, been associated. However, its etiology is still unknown. Se han asociado múltiples factores de riesgo; sin embar- abdomen agudo. Nowadays there exist histochemical markers to distinguish go, aún se desconoce su etiología. Actualmente existen different cell types, criteria, and scales to differentiate marcadores histoquímicos que permiten diferenciar los between primary and secondary intestinal lymphomas. distintos tipos celulares así como los criterios y escalas The definitive diagnosis is obtained with a histopathologic para distinguir entre linfomas intestinales primarios y and immunohistochemical study of the extracted surgical secundarios. El diagnóstico definitivo se logra con el piece. Some studies such as endoscopy, CAT scan or estudio histopatológico e inmunohistoquímico de la pieza capsule endoscopy and double balloon enteroscopy have extraída quirúrgica o endoscópicamente. -

Kaplan USMLE Step 2 CK Surgery Lecture Notes2018

USMLE ® • UP-TO-DATE ® STEP 2 CK STEP Updated annually by Kaplan’s all-star faculty STEP2 CK • INTEGRATED Lecture Notes 2018 Notes Lecture Packed with bridges between specialties and basic science Lecture Notes 2018 • TRUSTED Used by thousands of students each year to ace the exam USMLE Surgery Surgery Tell us what you think! Visit kaptest.com/booksfeedback and let us know about your book experience. ISBN: 978-1-5062-2822-8 kaplanmedical.com 9 7 8 1 5 0 6 2 2 8 2 2 8 USMLE® is a joint program of The Federation of State Medical Boards of the United States, Inc. and the National Board of Medical Examiners. USMLE® is a joint program of the Federation of State Medical Boards (FSMB) and the National Board of Medical Examiners (NBME), neither of which sponsors or endorses this product. 978-1-5062-2822-8_USMLE_Step2_CK_Surgery_Course_CVR.indd 1 6/21/17 10:58 AM ® STEP 2 CK Lecture Notes 2018 USMLE Surgery USMLE® is a joint program of The Federation of State Medical Boards of the United States, Inc. and the National Board of Medical Examiners. S2 Surgery.indb 1 6/20/17 9:15 AM USMLE® is a joint program of the Federation of State Medical Boards (FSMB) and the National Board of Medical Examiners (NBME), neither of which sponsors or endorses this product. This publication is designed to provide accurate information in regard to the subject matter covered as of its publication date, with the understanding that knowledge and best practice constantly evolve. The publisher is not engaged in rendering medical, legal, accounting, or other professional service. -

Tumours of the Stomach Seen in Distal Disease, Whereas Diffuse Cancers Are Poorly Differentiated and Seen in Cardia Cancers

OESOPHAGUS AND STOMACH Intestinal cancers are usually well differentiated and more often Tumours of the stomach seen in distal disease, whereas diffuse cancers are poorly differentiated and seen in cardia cancers. Metastatic spread is by William H Allum direct infiltration, via lymphatics to regional and distant lymph nodes, haematogenous and transcoelomic, spreading throughout body cavities. Nodal status is based on the Japanese classification Abstract of lymph node drainage, which is divided into three tiers that are e Gastric tumours are either epithelial or stromal in origin. Benign tumours related to the principal arterial supply to the stomach (N1 3, are rare with the majority being malignant and mostly adenocarcinomas. Table 2). Classification of nodal stage has been modified Gastric lymphomas, gastrointestinal stromal tumours (GISTs) and gastric according to the number of nodes involved in relation to the carcinoid are less common and have variable cancer biology. Gastric number of nodes resected. The TNM classification has recently e adenocarcinoma is the eighth-commonest cancer in the UK. Proximally been revised TNM 7. In the revision oesophageal cancer situated cancers are most frequent. It is characterized by late presentation includes all cancers within 5 cm of the squamo-columnar junc- with 80% of patients presenting with locally advanced or distant meta- tion. All other cancers are classified as gastric. This is a pathological static disease. Recognition of early gastric cancer remains a challenge classification which has been recommended for implementation by in low-incidence areas. Improvements in imaging techniques have allowed more individualized, tailored and stage-related treatments. Outcome in localized cancers has improved with multi-modality therapies yet overall survival remains poor. -

Squamous Metaplasia of the Tracheal Epithelium in Children

Thorax: first published as 10.1136/thx.31.2.167 on 1 April 1976. Downloaded from Thorax (1976), 31, 167. Squamous metaplasia of the tracheal epithelium in children AVINASH MITHAL' and JOHN L. EMERY2 The Chest Clinic, Lincoln' and The Children's Hospital, Sheffield' Mithal, A. and Emery, J. L. (1976). Thorax, 31, 167-171. Squamous metaplasia of the tracheal epithelium in children. Thirty-seven (16%) tracheas from 2170 children showed squamous metaplasia. (Cases with tracheo-oesophageal fistula and congenital heart disease were excluded.) The metaplasia extended into the bronchi in 15 cases. Features of pulmonary retention were present in seven cases. Respiratory infection, probably viral, seemed to be the most significant causative factor in 20 children, including those with cystic fibrosis. Tracheal instrumentation was a possible factor in 11 cases but oxygen therapy alone did not seem important. The metaplasia was almost certainly congenital in one child and probably in two others but no stillborn infants showed metaplasia. In many children the metaplasia seemed to be due to a combination of factors. Squamous metaplasia of the trachea in childhood Tracheas from children with tracheo-oesophageal has been described in cases of measles (Gold- fistula and those with congenital heart disease or zieher, 1918), influenza (Askanazy, 1919), cystic other gross deformities were excluded. There were fibrosis of the pancreas (Zuelzer and Newton, thus 2331 tracheas available for study. Epithelium 1949), and following intubation of the trachea was absent in 16 cases. This left 2170 tracheas for http://thorax.bmj.com/ (Rasche and Kuhns, 1972) and tracheostomy histological analysis. (Sara, 1967; Sara and Reye, 1969). -

Squamous Metaplasia of Normal and Carcinoma in Situ of HPV 16-Immortalized Human Endocervical Cells1

[CANCER RESEARCH 52. 4254-4260, August I, 1992] Squamous Metaplasia of Normal and Carcinoma in Situ of HPV 16-Immortalized Human Endocervical Cells1 Qi Sun, Kouichiro Tsutsumi, M. Brian Kelleher, Alan Pater, and Mary M. Pater2 Division of Basic Medical Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, Memorial University of Newfoundland, St. John's, Newfoundland, Canada A1B ÌV6 ABSTRACT genomic DNA, most frequently of HPV 16, has been detected in 90% of the cervical carcinomas and are found to be actively The importance of cervical squamous metaplasia and human papil- expressed (6, 7). HPV 16 DNA has been used to transform lomavirus 16 (HPV 16) infection for cervical carcinoma has been well human foreskin and ectocervical keratinocytes (8, 9). It immor established. Nearly 87% of the intraepithelial neoplasia of the cervix occur in the transformation zone, which is composed of squamous meta- talizes human keratinocytes efficiently, producing cell clones plastic cells with unclear origin. HPV DNA, mostly HPV 16, has been with indefinite life span in culture. Different approaches have found in 90% of cervical carcinomas, but only limited experimental data been taken to examine the behavior of these immortalized cell are available to discern the role of HPV 16 in this tissue specific onco- lines in conditions allowing squamous differentiation (10, 11). genesis. We have initiated in vivo studies of cultured endocervical cells After transplantation in vivo, the HPV 16-immortalized kerat as an experimental model system for development of cervical neoplasia. inocytes retain thépotential for squamous differentiation, Using a modified in vivo implantation system, cultured normal endocer forming abnormal epithelium without dysplastic changes at vical epithelial cells formed epithelium resembling squamous metapla early passages and with various dysplastic changes only after sia, whereas those immortalized by HPV 16 developed into lesions long periods of time in culture (10). -

Immunohistochemistry Stain Offerings

immunohistochemistry stain offerings TRUSTED PATHOLOGISTS. INVALUABLE ANSWERS.™ MARCHMAY 20172021 www.aruplab.com/ap-ihcaruplab.com/ap-ihc InformationInformation in this brochurein this brochure is current is current as of as May of March 2021. 2017. All content All content is subject is subject to tochange. change. Please contactPlease ARUPcontact ClientARUP Services Client Services at 800-522-2787 at (800) 522-2787 with any with questions any questions or concerns.or concerns. ARUP LABORATORIES As a nonprofit, academic institution of the University of Utah and its Department We believe in of Pathology, ARUP believes in collaborating, sharing and contributing to laboratory science in ways that benefit our clients and their patients. collaborating, Our test menu is one of the broadest in the industry, encompassing more sharing and than 3,000 tests, including highly specialized and esoteric assays. We offer comprehensive testing in the areas of genetics, molecular oncology, pediatrics, contributing pain management, and more. to laboratory ARUP’s clients include many of the nation’s university teaching hospitals and children’s hospitals, as well as multihospital groups, major commercial science in ways laboratories, and group purchasing organizations. We believe that healthcare should be delivered as close to the patient as possible, which is why we support that provide our clients’ efforts to be the principal healthcare provider in the communities they serve by offering highly complex assays and accompanying consultative support. the best value Offering analytics, consulting, and decision support services, ARUP provides for the patient. clients with the utilization management tools necessary to prosper in this time of value-based care. -

Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Breast As a Clinical Diagnostic Challenge

582 MOLECULAR AND CLINICAL ONCOLOGY 8: 582-586, 2018 Squamous cell carcinoma of the breast as a clinical diagnostic challenge KATARZYNA JAKUBOWSKA1, LUIZA KAŃCZUGA‑KODA1, WOJCIECH KISIELEWSKI2, MARIUSZ KODA3 and WALDEMAR FAMULSKI1,2 1Department of Pathomorphology, Comprehensive Cancer Center, 15‑027 Białystok; Departments of 2Medical Pathomorphology and 3General Pathomorphology, Medical University of Białystok, 15‑269 Białystok, Poland Received September 17, 2017; Accepted December 14, 2017 DOI: 10.3892/mco.2018.1581 Abstract. Squamous cell carcinoma (SqCC) of the breast metaplasia of ductal and lobular epithelial cells can be should be differentiated between the primary skin keratinizing linked with fat necrosis and infracted ademonas. Squamous squamous carcinoma and squamous metaplastic cancer. In the cell carcinoma should be differentiated between lesions of current study, the cases of two patients who were diagnosed keratinizing squamous carcinoma and squamous metaplasia with SqCC originated from skin and the breast were discussed. associated to mammary carcinoma (2). The characteristic A fine-needle aspiration biopsy confirmed the presence features of metaplastic cell carcinoma include: i) primary of atypical squamous cells. In both cases, the microscopic carcinoma without other neoplastic components such as ductal examination of the surgical specimen revealed a malignant or mesenchymal elements, ii) the tumor origin is independent neoplasm differentiated into SqCC characterized by keratin- of the overlying skin and nipple and iii) absence of primary izing cancer cells with abundant eosiphilic cytoplasm with epidermoid tumors present in other site (oral cavity, bronchus, large, hyperchromatic vesicular nuclei. Immunohistochemical esophagus, bladder, cervix ect.) (3). However, squamous studies showed negative for progesterone and estrogen recep- metaplastic carcinoma should be also differentiated with pure tors and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2. -

Chapter 1 Cellular Reaction to Injury 3

Schneider_CH01-001-016.qxd 5/1/08 10:52 AM Page 1 chapter Cellular Reaction 1 to Injury I. ADAPTATION TO ENVIRONMENTAL STRESS A. Hypertrophy 1. Hypertrophy is an increase in the size of an organ or tissue due to an increase in the size of cells. 2. Other characteristics include an increase in protein synthesis and an increase in the size or number of intracellular organelles. 3. A cellular adaptation to increased workload results in hypertrophy, as exemplified by the increase in skeletal muscle mass associated with exercise and the enlargement of the left ventricle in hypertensive heart disease. B. Hyperplasia 1. Hyperplasia is an increase in the size of an organ or tissue caused by an increase in the number of cells. 2. It is exemplified by glandular proliferation in the breast during pregnancy. 3. In some cases, hyperplasia occurs together with hypertrophy. During pregnancy, uterine enlargement is caused by both hypertrophy and hyperplasia of the smooth muscle cells in the uterus. C. Aplasia 1. Aplasia is a failure of cell production. 2. During fetal development, aplasia results in agenesis, or absence of an organ due to failure of production. 3. Later in life, it can be caused by permanent loss of precursor cells in proliferative tissues, such as the bone marrow. D. Hypoplasia 1. Hypoplasia is a decrease in cell production that is less extreme than in aplasia. 2. It is seen in the partial lack of growth and maturation of gonadal structures in Turner syndrome and Klinefelter syndrome. E. Atrophy 1. Atrophy is a decrease in the size of an organ or tissue and results from a decrease in the mass of preexisting cells (Figure 1-1).