Corridor Transportation Management for Highway

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority

y NOTE WONOERLAND 7 THERE HOLDERS Of PREPAID PASSES. ON DECEMBER , 1977 WERE 22,404 2903 THIS AMOUNTS TO AN ESTIMATED (44 ,608 ) PASSENGERS PER DAY, NOT INCLUDED IN TOTALS BELOW REVERE BEACH I OAK 8R0VC 1266 1316 MALOEN CENTER BEACHMONT 2549 1569 SUFFOLK DOWNS 1142 ORIENT< NTS 3450 WELLINGTON 5122 WOOO ISLANC PARK 1071 AIRPORT SULLIVAN SQUARE 1397 6668 I MAVERICK LCOMMUNITY college 5062 LECHMERE| 2049 5645 L.NORTH STATION 22,205 6690 HARVARD HAYMARKET 6925 BOWDOIN , AQUARIUM 5288 1896 I 123 KENDALL GOV CTR 1 8882 CENTRAL™ CHARLES^ STATE 12503 9170 4828 park 2 2 766 i WASHINGTON 24629 BOYLSTON SOUTH STATION UNDER 4 559 (ESSEX 8869 ARLINGTON 5034 10339 "COPLEY BOSTON COLLEGE KENMORE 12102 6102 12933 WATER TOWN BEACON ST. 9225' BROADWAY HIGHLAND AUDITORIUM [PRUDENTIAL BRANCH I5I3C 1868 (DOVER 4169 6063 2976 SYMPHONY NORTHEASTERN 1211 HUNTINGTON AVE. 13000 'NORTHAMPTON 3830 duole . 'STREET (ANDREW 6267 3809 MASSACHUSETTS BAY TRANSPORTATION AUTHORITY ricumt inoicati COLUMBIA APFKOIIUATC 4986 ONE WAY TRAFFIC 40KITT10 AT RAPID TRANSIT LINES STATIONS (EGLESTON SAVIN HILL 15 98 AMD AT 3610 SUBWAY ENTRANCES DECEMBER 7,1977 [GREEN 1657 FIELDS CORNER 4032 SHAWMUT 1448 FOREST HILLS ASHMONT NORTH OUINCY I I I 99 8948 3930 WOLLASTON 2761 7935 QUINCY CENTER M b 6433 It ANNUAL REPORT Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2014 https://archive.org/details/annualreportmass1978mass BOARD OF DIRECTORS 1978 ROBERT R. KILEY Chairman and Chief Executive Officer RICHARD D. BUCK GUIDO R. PERERA, JR. "V CLAIRE R. BARRETT THEODORE C. LANDSMARK NEW MEMBERS OF THE BOARD — 1979 ROBERT L. FOSTER PAUL E. MEANS Chairman and Chief Executive Officer March 20, 1979 - January 29. -

Ocm57326772-1934.Pdf (340.9Kb)

*6^ 5-7 36" Public Document No. 142 <5hr Cnmmnnruralth nf Mw&aatliUBtttB ANNUAL REPORT OF THE DIVISION OF METROPOLITAN PLANNING FOR THE YEAR ENDING NOVEMBER 30 1934 Publication of this Document Approved by the Commission on Administration and Finance 300—4-'35. Order 4293. Oil)? Cummnttuwaltlj of M&BmtfyuwttB DIVISION OF METROPOLITAN PLANNING 20 Somerset St., Boston, November 30, 1934. To the Honorable Senate and House of Representatives in General Court' Assembled: The Division of Metropolitan Planning herewith respectfully submits its annual report for the year ending November 30, 1934. Special Reports In accordance with instructions from the General Court, this Division has been engaged this year in the investigation and preparation of reports on the following matters having to do with proposed rapid transit extensions or im- provements in the District. 1. Removal of the Washington Street Elevated Structure in Boston, Rox- bury and West Roxbury and substitution therefor of a subway in accordance with Chapter 36 of the Resolves of 1933. This resolve called for a joint report by the Metropolitan Planning Division and the Boston Transit Department. 2. Advisibility of extending the Cambridge Subway to Arlington and the rapid transit system from Lechmere Square in Cambridge to Arlington in accordance with Chapter 22 of the Resolves of 1934. 3. Advisability of extending the rapid transit system in the city of Boston from Forest Hills Station to Spring St. or the Dedham line in accordance with Chapter 40 of the Resolves of 1934. These reports must be filed early in December of 1934. In none of these re- ports is the Division making definite recommendations but we feel that a sin- cere effort must be made to provide for the future financing of desirable and needed rapid transit extensions or improvements and therefore we are filing a bill providing for the setting up of a fund which will accumulate for this purpose and make such improvements possible without the burden of long- term bond issues. -

Draft TIP Transit Programming MBTA Project

MBTA Federal Capital Program ‐ FTA Formula Funds FFY 2018‐2023 TIP Project Descriptions ‐ Provided for Informational Purposes For Presentation to the Boston MPO on 3/22/2018 TIP Project Name Project Description 5307 ‐ Revenue Vehicle Program Commuter Rail Locomotive Reliability This program will restore coaches and locomotives, beyond their useful life, to a state of Program good repair to support service and winter resilliency efforts Procurement of 60‐foot Dual Mode Articulated (DMA) buses to replace the existing fleet of DMA Bus Replacement 32 Silver Line Bus Rapid Transit buses and to provide for ridership expansion projected as a result of Silver Line service extension to Chelsea. Green Line Light Rail Fleet Replacement ‐ Development of technical specifications for the procurement of light rail vehicles to replace Design the existing fleet that is approaching the end of its service life. Overhaul of locomotives in operation on commuter rail lines systemwide in order to improve Locomotive Overhaul reliability. Replacement of major systems and refurbishment of seating and other customer facing MBTA Catamaran Overhaul components on two catamarans (Lightning and Flying Cloud). Midlife Overhaul of 25 New Flyer Allison Overhaul of 25 hybrid buses, brought into service in 2009 and 2010, to enable optimal Hybrid 60 ft Articulated Buses reliability through the end of their service life. Overhaul of 32 Neoplan 60' DMA Buses Overhaul of the Neoplan 60' Dual Mode Articulated buses that operate on the MBTA Silver (5307) Line Bus Rapid Transit routes. Overhaul of 33 Kawasaki 900 Series Bi‐Level Overhaul and upgrade of existing systems on commuter rail coaches that were brought into Coaches service in 2005 to enable optimal reliability through the end of their service life. -

Federal Register/Vol. 68, No. 109/Friday, June 6, 2003/Notices

Federal Register / Vol. 68, No. 109 / Friday, June 6, 2003 / Notices 33967 ADDRESS: Foster Armstrong House, or faxed comments should be submitted the significance of these properties Montague NJ 07827. by June 23, 2003. under the National Register criteria for evaluation may be forwarded by United The agenda will include reports from Carol D. Shull, Citizen Advisory Commission members States Postal Service, to the National Keeper of the National Register of Historic Register of Historic Places, National including setting dates and times for Places. future meetings, and other topics as Park Service, 1849 C St. NW., 2280, deemed necessary by the members. ILLINOIS Washington, DC 20240; by all other carriers, National Register of Historic Acting Superintendent Doyle Nelson Pike County will give a report on various park issues, Places, National Park Service, 1201 Eye Shastid, John, House, 326 East Jefferson, St. NW., 8th floor, Washington DC including an update on the park’s Pittsfield, 03000579. historic leasing program. The agenda is 20005; or by fax, 202–371–6447. Written set up to invite the public to bring MARYLAND or faxed comments should be submitted issues of interest before the Baltimore Independent City by June 23, 2003. Commission. These issues typically Baltimore City College, 3320 The Alameda, Carol D. Shull, include treatment of historic buildings Baltimore (Independent City), 03000573. Keeper of the National Register of Historic within the recreation area, monitoring of Places. waste water facilities outside the MASSACHUSETTS recreation area but empyting into the Norfolk County ALASKA Delaware River, and wildlife Blue Hills Parkway, (Metropolitan Park Juneau Borough—Census Area management issues. -

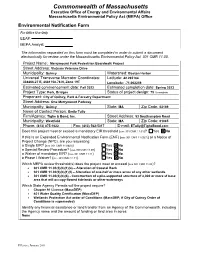

Commonwealth of Massachusetts Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs Massachusetts Environmental Policy Act (MEPA) Office

Commonwealth of Massachusetts Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs Massachusetts Environmental Policy Act (MEPA) Office Environmental Notification Form For Office Use Only EEA#: MEPA Analyst: The information requested on this form must be completed in order to submit a document electronically for review under the Massachusetts Environmental Policy Act, 301 CMR 11.00. Project Name: Merrymount Park Pedestrian Boardwalk Project Street Address: Vietnam Veterans Drive Municipality: Quincy Watershed: Boston Harbor Universal Transverse Mercator Coordinates: Latitude: 42.265164 334866.27 E, 4681158.76 N, Zone 19T Longitude: -71.002239 Estimated commencement date: Fall 2022 Estimated completion date: Spring 2023 Project Type: Park, Bridges Status of project design: 75 %complete Proponent: City of Quincy, Park & Forestry Department Street Address: One Merrymount Parkway Municipality: Quincy State: MA Zip Code: 02169 Name of Contact Person: Emily Tully Firm/Agency: Tighe & Bond, Inc. Street Address: 53 Southampton Road Municipality: Westfield State: MA Zip Code: 01085 Phone: (413) 875-1622 Fax: (413) 562-5317 E-mail: [email protected] Does this project meet or exceed a mandatory EIR threshold (see 301 CMR 11.03)? Yes No If this is an Expanded Environmental Notification Form (ENF) (see 301 CMR 11.05(7)) or a Notice of Project Change (NPC), are you requesting: a Single EIR? (see 301 CMR 11.06(8)) Yes No a Special Review Procedure? (see 301CMR 11.09) Yes No a Waiver of mandatory EIR? (see 301 CMR 11.11) Yes No a Phase I Waiver? (see -

Charles W. Bradley III, AIA, NCARB Charles W

the ARCH Resume Professional Group inc. architecture & planning Charles W. Bradley III, AIA, NCARB Charles W. Bradley III, aia PrincipalPrincipal Education Professional Experience Office: 260Massachusetts Blue Hills Parkway Institute of Technology Mr. Bradley is President and founder of The Arch Professional Milton,Cambridge, MA 02186 Massachusetts Group, Inc. (APG). The Firm’s past and present body of M.S. Architectural Studies. 1983 work includes Residential, Commercial, Educational, and c:Rensselaer617.538.1515 Polytechnic Institute Institutional projects with construction budgets ranging from f:Troy,617.296.3633 New York $300,000 to $1.5 Million. M.S. Environmental Studies. 1981 Bachelor of Architecture. 1981 Project Experience: Bachelor of Science in Building Sciences. 1980 [email protected] Historic Restoration / Adaptive Re-use Architectural Registration • 234 Berkeley Street, Boston, MA Massachusetts – License No. 9499 - Senior Designer/Draftsperson for the $2.8 Million renovation North Carolina – License No. 10300 to the old Bonwit Teller Building into new retail space for Georgia – License No. RA012393 Louis Boston. NCARB-National Council of Architectural Registration Boards - Certificate No. 49337 Renovation • Department of Veterans’ Affairs Headquarters, Washington, Certifications DC Minority Owned Business Enterprise (MBE) - Project Architect - Construction Administration - Massachusetts Supplier Diversity Office (SDO) • 745 Boylston Street, Boston, MA - Junior Designer/Technical Staff for the renovation for Disadvantaged Business Enterprise (DBE) office/retail use. - Massachusetts Supplier Diversity Office (SDO) • 40 Summer Street, Boston, MA Academic - Junior Designer/Technical Staff for the renovation for office/retail use. • Wentworth Institute of Technology - Part-time Instructor (1992-1993 academic year) Institutional / Office • M.I.T. - Research Affiliate [1992-1993]; Visiting Scholar [1991- 1992]; Teaching Assistant [1982] • Morning Star Baptist Church, Mattapan, MA • R.P.I. -

Changes to Transit Service in the MBTA District 1964-Present

Changes to Transit Service in the MBTA district 1964-2021 By Jonathan Belcher with thanks to Richard Barber and Thomas J. Humphrey Compilation of this data would not have been possible without the information and input provided by Mr. Barber and Mr. Humphrey. Sources of data used in compiling this information include public timetables, maps, newspaper articles, MBTA press releases, Department of Public Utilities records, and MBTA records. Thanks also to Tadd Anderson, Charles Bahne, Alan Castaline, George Chiasson, Bradley Clarke, Robert Hussey, Scott Moore, Edward Ramsdell, George Sanborn, David Sindel, James Teed, and George Zeiba for additional comments and information. Thomas J. Humphrey’s original 1974 research on the origin and development of the MBTA bus network is now available here and has been updated through August 2020: http://www.transithistory.org/roster/MBTABUSDEV.pdf August 29, 2021 Version Discussion of changes is broken down into seven sections: 1) MBTA bus routes inherited from the MTA 2) MBTA bus routes inherited from the Eastern Mass. St. Ry. Co. Norwood Area Quincy Area Lynn Area Melrose Area Lowell Area Lawrence Area Brockton Area 3) MBTA bus routes inherited from the Middlesex and Boston St. Ry. Co 4) MBTA bus routes inherited from Service Bus Lines and Brush Hill Transportation 5) MBTA bus routes initiated by the MBTA 1964-present ROLLSIGN 3 5b) Silver Line bus rapid transit service 6) Private carrier transit and commuter bus routes within or to the MBTA district 7) The Suburban Transportation (mini-bus) Program 8) Rail routes 4 ROLLSIGN Changes in MBTA Bus Routes 1964-present Section 1) MBTA bus routes inherited from the MTA The Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA) succeeded the Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA) on August 3, 1964. -

Regionwide Suburban Transit Opportunities Study Phase II

Regionwide Suburban Transit Opportunities Study Phase II A report produced by the Central Transportation Planning Staff for the Boston Region Metropolitan Planning Organization Regionwide Suburban Transit Opportunities Study Phase II Project Manager Clinton Bench Authors Thomas J. Humphrey Heather Ostertog Contributing Staff Paul Reim Cartography Mary McShane Cover Design Jane M. Gillis Cover Photographs Carol Gautreau Bent Kenneth Dumas Central Transportation Planning Staff, directed by the Boston Region Metropolitan Planning Organization. The MPO is com- posed of state and regional agencies and authorities, and local governments. December 2005 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. SUMMARY OF FINDINGS.................................................................................................1 Overview...........................................................................................................................1 Suggested Routes .............................................................................................................2 Wellesley .........................................................................................................................2 Winchester.......................................................................................................................2 Westwood........................................................................................................................2 Canton..............................................................................................................................3 -

Annual Report of the Metropolitan District Commission

Public Document No. 48 W$t Commontoealtfj of iWa&sacfmsfetta ANNUAL REPORT OF THE Metropolitan District Commission For the Year 1935 Publication or this Document Approved by the Commission on Administration and Finance lm-5-36. No. 7789 CONTENTS PAGE I. Organization and Administration . Commission, Officers and Employees . II. General Financial Statement .... III. Parks Division—Construction Wellington Bridge Nonantum Road Chickatawbut Road Havey Beach and Bathhouse Garage Nahant Beach Playground .... Reconstruction of Parkways and Boulevards Bridge Repairs Ice Breaking in Charles River Lower Basin Traffic Control Signals IV. Maintenance of Parks and Reservations Revere Beach Division .... Middlesex Fells Division Charles River Lower Basin Division . Bunker Hill Monument .... Charles River Upper Division Riverside Recreation Grounds . Blue Hills Division Nantasket Beach Reservation Miscellaneous Bath Houses Band Concerts Civilian Conservation Corps Federal Emergency Relief Activities . Public Works Administration Cooperation with the Municipalities . Snow Removal V. Special Investigations VI. Police Department VII. Metropolitan Water District and Works Construction Northern High Service Pipe Lines . Reinforcement of Low Service Pipe Lines Improvements for Belmont, Watertown and Arlington Maintenance Precipitation and Yield of Watersheds Storage Reservoirs .... Wachusett Reservoir . Sudbury Reservoir Framingham Reservoir, No. 3 Ashland, Hopkinton and Whitehall Reservoirs and South Sud- bury Pipe Lines and Pumping Station Framingham Reservoirs Nos. 1 and 2 and Farm Pond Lake Cochituate . Aqueducts Protection of the Water Supply Clinton Sewage Disposal Works Forestry Hydroelectric Service Wachusett Station . Sudbury Station Distribution Pumping Station Distribution Reservoirs . Distribution Pipe Lines . T) 11 P.D. 48 PAGE Consumption of Water . 30 Water from Metropolitan Water Works Sources used Outside of the Metropolitan Water District VIII. -

Report of the Board of Metropolitan Park Commissioners (1898)

A Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/reportofboardofm00mass_4 PUBLIC DOCUMENT No. 48. REPORT ~ Board of Metropolitan Park Commissioners. J^ANUARY, 1899. BOSTON : W RIGHT & POTTER PRINTING CO., STATE PRINTERS, 18 Post Office Square. 1899. A CONTENTS. PAGE Report of the Commissioners, 5 Report of the Secretary, 18 Report of the Landscape Architects, 47 Report of the Engineer, 64 Financial Statement, . 86 Analysis of Payments, 99 Claims (chapter 366 of the Acts of 1898), 118 KEPOKT. The Metropolitan Park Commission presents herewith its sixth annual report. At the presentation of its last report the Board was preparing to continue the acquirement of the banks of Charles River, and was engaged in the investigation of avail- able shore frontages and of certain proposed boulevards. Towards the close of its last session the Legislature made an appropriation of $1,000,000 as an addition to the Metropolitan Parks Loan, but further takings were de- layed until the uncertainties of war were clearly passed. Acquirements of land and restrictions have been made or provided for however along Charles River as far as Hemlock Gorge, so that the banks for 19 miles, except where occu- pied by great manufacturing concerns, are in the control either of this Board or of some other public or quasi public body. A noble gift of about 700 acres of woods and beau- tiful intervales south of Blue Hills and almost surroundingr Ponkapog Pond has been accepted under the will of the late ' Henry L. Pierce. A field in Cambridge at the rear of « Elm- wood," bought as a memorial to James Russell Lowell, has been transferred to the care of this Board, one-third of the purchase price having been paid by the Commonwealth and the remaining two-thirds by popular subscription, and will be available if desired as part of a parkway from Charles River to Fresh Pond. -

Appendix E Detailed Case Studies

Guidelines for Providing Access to Public Transportation Stations APPENDIX E DETAILED CASE STUDIES Revised Final Report 2011 Page E-1 Detailed Case Studies Guidelines for Providing Access to Public Transportation Stations TABLE OF CONTENTS Case Study Summary ............................................................................................................................... E-3 Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) .............................................................................................................. E-7 Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority (Metro) ........................................... E-21 Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority (MARTA) ................................................................ E-33 Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA) ..................................................................... E-41 Metro-North Railroad ............................................................................................................................. E-57 New Jersey Transit (NJT) ....................................................................................................................... E-67 OC Transpo .............................................................................................................................................. E-81 Regional Transit District Denver (RTD) ............................................................................................... E-93 Sound Transit ........................................................................................................................................ -

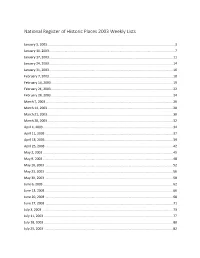

National Register of Historic Places Weekly Lists for 2003

National Register of Historic Places 2003 Weekly Lists January 3, 2003 ............................................................................................................................................. 3 January 10, 2003 ........................................................................................................................................... 7 January 17, 2003 ......................................................................................................................................... 11 January 24, 2003 ......................................................................................................................................... 14 January 31, 2003 ......................................................................................................................................... 16 February 7, 2003 ......................................................................................................................................... 18 February 14, 2003 ....................................................................................................................................... 19 February 21, 2003 ....................................................................................................................................... 22 February 28, 2003 ....................................................................................................................................... 24 March 7, 2003 ............................................................................................................................................