University of Oklahoma Graduate College

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chief (Tin Doi) Tendoy 1834 -1907 Leader of a Mixed Band of Bannock

Introducing 2012 Montana Cowboy Hall of Fame Inductee… Chief (Tin Doi) Tendoy 1834 -1907 Leader of a mixed band of Bannock, Lemhi, Shoshone & Tukuarika tribes Chief Tendoy (Tin Doi) was born in the Boise River region of what is now the state of Idaho in approximately 1834. The son of father Kontakayak (called Tamkahanka by white settlers), a Bannock Shoshone and a"Sheep Eater" Shoshone mother who was a distant cousin to the mother of Chief Washakie. Tendoy was the nephew of Cameahwait and Sacajewea. Upon the murder of Chief Old Snag by Bannack miners in 1863 Tendoy became chief of the Lemhi Shoshone. Revered by white settlers as a peacemaker Chief Tendoy kept members of his tribe from joining other tribes in their war with the whites. He led his people, known as Tendoy's Band, more than 40 years. He was a powerful force to reckoned with in negotiations with the federal government and keeping his tribe on peaceful terms with oncoming white settlers. In 1868, with his band of people struggling to survive as miners and settlers advanced upon their traditional hunting, fishing and gathering grounds, Chief Tendoy and eleven fellow Lemhi and Bannock leaders signed a treaty surrendering their tribal lands in exchange for an annual payment by the federal government as well as two townships along the north fork of the Salmon River. The treaty, having never been ratified, forced the tribe to move to a desert reservation known as Fort Hall, created for the Shoshone tribes in 1867. Chief Tendoy refused, expecting what the government had promised. -

Guide to NATIVE AMERICAN HISTORY RESOURCES

Guide to NATIVE AMERICAN HISTORY RESOURCES Crow man and woman inside tipi, 1902-1910 Richard Throssel Papers #02394. Compiled By: Kim Mainardis 1998 Revised By: James Deagon and Leslie Waggener 2008 INTRODUCTION The American Heritage Center (AHC) is ON-LINE ACCESS the University of Wyoming’s archives, Bibliographic access to materials can be rare books and manuscripts repository. reached through University of Wyoming’s AHC collections go beyond Wyoming or library catalog, OCLC (Online Computer the region’s borders to include the Library Center), or the Rocky Mountain American West, the mining and petroleum Online Archive (www.rmoa.org). industries, U.S. politics and world affairs, environment and natural resources, HOURS OF SERVICE journalism, transportation, the history of Monday 10:00am- 9:00pm books, and 20th century entertainment. Tuesday- Friday 8:00am-5:00 pm The American Heritage Center traces its FOR MORE INFORMATION beginnings to the efforts of Dr. Grace PLEASE CALL OR WRITE Raymond Hebard, an engineer, lawyer, American Heritage Center suffragist, historian, and University of University of Wyoming Wyoming professor, librarian, and trustee. Dept. 3924 From approximately 1895 to 1935, 1000 E. University Ave. Hebard collected source materials relating Laramie, WY 82071 to the history of Wyoming, the West, (307)766-4114 (Main number) emigrant trails, and Native Americans. (307)766-3756 (Reference Department) (307)766-5511 (FAX) In 1945, University Librarian Lola Homsher established the Western History Collection at the University of Wyoming, with the materials gathered by Hebard as its nucleus. An active collecting program ensued, and in 1976, the name was changed to the American Heritage Center to reflect the archives’ broad holdings relating to American history. -

The Biography of James K

The Biography of James K. Moore From Original Manuscript Compiled by Evelyn Bell Copyright ©2004 by Henry E. Stamm, IV, editor INTRODUCTION During the reservation era of the late 19th century, it took political connections and well-placed references to win contracts as either military sutlers or Indian reservation traders. James Kerr Moore, the Indian trader for the Wind River Reservation and military sutler at Fort Washakie, Wyoming, from the 1870s until the early 1900s, had both. His successes, however, came from hard work, a willingness to learn, good timing, and honesty in his business dealings. FAMILY HISTORY & EARLY YEARS James K. Moore was born into a family of middling means—his paternal grandfather, James Moore, had emigrated from Ireland about 1801 and joined the printing firm of Blanchard-Mohun in Washington, D.C. His duties included printing the newspaper, The National Intelligencer. Later, he worked for the U.S. Department of the Treasury as an accountant, and remained in that position until his death in 1853. James’s father, Robert Lowry Moore, was born in 1815 and moved to Henry County, Georgia about 1838, with hopes of participating in one of the land lotteries sponsored by Georgia. (Georgia passed a series of lotteries, beginning in 1805, as a means to disperse the lands that were taken from the Creek and Cherokee Indians). He was too late, as the last lottery took place in 1832, but his new father-in-law, William H. Agnew, was one of the lucky winners. Robert’s first wife, Ann Johnson Askew, died in September 1840 (probably in childbirth), whereupon he married her younger sister, Mary, a month later. -

The Southern Arizona Guest Ranch As a Symbol of the West

The Southern Arizona guest ranch as a symbol of the West Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Norris, Frank B. (Frank Blaine), 1950-. Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 07/10/2021 15:00:58 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/555065 THE SOUTHERN ARIZONA GUEST RANCH AS A SYMBOL OF THE WEST by Frank Blaine Norris A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF GEOGRAPHY, REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT, AND URBAN PLANNING In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS WITH A MAJOR IN GEOGRAPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 1 9 7 6 Copyright 1976 Frank Blaine Norris STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfill ment of requirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowl edgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the copyright holder. SIGNED: APPROVAL BY THESIS DIRECTOR This thesis has been approved on the date shown below: ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This thesis is the collective effort of many, and to each who played a part in its compilation, I am indebted. -

The Plains Sioux and US Coloniali

Cambridge University Press 0521793467 - The Plains Sioux and U. S. Colonialism from Lewis and Clark to Wounded Knee Jeffrey Ostler Index More information Index Act of March 2, 1889. See treaties and American Fur Company, 28, 30, 31 agreements American Horse, 110n.4, 110n.5, 139n.39, Adams,David Wallace, 153 364n.8 Adas,Michael, 250 at Carlisle, 155 Afraid of the Enemy, 348 and Crazy Horse, 100, 101 Afraid of Hawk, 197n.12 and 1889 agreement, 237, 238 Agard,Louis, 227n.28 and Ghost Dance, 272, 310, 310n.62, agencies 311 Indians’ perceptions of, 54 and McGillycuddy, 204, 205 purposes of, 54 and Red Cloud, 203, 205 see also names of specific agencies and Wounded Knee, 346, 365–6 agency bands. See nonmilitants American Horse,Robert, 152 Agency Council. See Pine Ridge Agency American Indian Movement, 363n.5 Council Anderson,Gary, 121 agents Anderson,Harry H., 78 colonial tools of, 159, 164, 166, 174–6, annuities 177, 204, 278 control of, 204 contradictory acts of, 196 and Crook Commission, 234 goals of, 54 in 1868 Treaty, 50, 129 resistance to, 54 problems with, 130 agriculture. See farming antelope. See small game alcohol Apaches, 60 Americans’ abuse of, 215 Apiatan, 254n.29 and fur trade, 29–30 Arapahoes, 34, 45, 52, 59, 60, 69, 102 Sioux fears of, 215 and Ghost Dance, 243, 246, 279 at Wounded Knee, 336, 352 Arikaras, 22, 25, 32 Allen,Alvaren, 214 army officers Allison Commission, 61 attitude toward reformers of, 47, 120 Allison,William B., 61 “mastery” of “savagery” by, 94 allotment and western army in 1880s, 304–5 in Dawes Severalty Act, 221 see also names of specific officers Sioux opposition to, 221–2, 231–2 Arrow Creek,battle of, 53 Sioux support for, 230–1 artifacts see also Dawes Sioux Bill acquisition of, 146 Ambrose,Stephen, 92 Ash Hollow, 41, 42, 43 371 © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 0521793467 - The Plains Sioux and U. -

Chapter 3 – Community Profile

Chapter 3: COMMUNITY PROFILE The Physical Environment, Socio-Economics and History of Fremont County Natural and technological hazards impact citizens, property, the environment and the economy of Fremont County. These hazards expose Fremont County residents, businesses and industries to financial and emotional costs. The risk associated with hazards increases as more people move into areas. This creates a need to develop strategies to reduce risk and loss of lives and property. Identifying risks posed by these hazards, and developing strategies to reduce the impact of a hazard event can assist in protecting life and property of citizens and communities. Physical / Environment Geology Much of Fremont County is made up of the 8,500 square mile Wind River Basin. This basin is typical of other large sedimentary and structural basins in the Rocky Mountain West. These basins were formed during the Laramide Orogeny from 135 to 38 million years ago. Broad belts of folded and faulted mountain ranges surround the basin. These ranges include the Wind River Range on the west, the Washakie Range and Owl Creeks and southern Big Horn Mountains on the north, the Casper Arch on the east, and the Granite Mountains on the south. The center of the basin is occupied by relatively un-deformed rocks of more recent age. Formations of every geologic age exist in Fremont County. These create an environment of enormous geologic complexity and diversity. The geology of Fremont County gives us our topography, mineral resources, many natural hazards and contributes enormously to our cultural heritage. Topography Fremont County is characterized by dramatic elevation changes. -

The Sacagawea Mystique: Her Age, Name, Role and Final Destiny Columbia Magazine, Fall 1999: Vol

History Commentary - The Sacagawea Mystique: Her Age, Name, Role and Final Destiny Columbia Magazine, Fall 1999: Vol. 13, No. 3 By Irving W. Anderson EDITOR'S NOTE The United States Mint has announced the design for a new dollar coin bearing a conceptual likeness of Sacagawea on the front and the American eagle on the back. It will replace and be about the same size as the current Susan B. Anthony dollar but will be colored gold and have an edge distinct from the quarter. Irving W. Anderson has provided this biographical essay on Sacagawea, the Shoshoni Indian woman member of the Lewis and Clark expedition, as background information prefacing the issuance of the new dollar. THE RECORD OF the 1804-06 "Corps of Volunteers on an Expedition of North Western Discovery" (the title Lewis and Clark used) is our nation's "living history" legacy of documented exploration across our fledgling republic's pristine western frontier. It is a story written in inspired spelling and with an urgent sense of purpose by ordinary people who accomplished extraordinary deeds. Unfortunately, much 20th-century secondary literature has created lasting though inaccurate versions of expedition events and the roles of its members. Among the most divergent of these are contributions to the exploring enterprise made by its Shoshoni Indian woman member, Sacagawea, and her destiny afterward. The intent of this text is to correct America's popular but erroneous public image of Sacagawea by relating excerpts of her actual life story as recorded in the writings of her contemporaries, people who actually knew her, two centuries ago. -

Wsgs-2002-Gn-74.Pdf (5.967Mb)

WWyyoommiinngg GGeeoo--nnootteess NNuummbbeerr7744 In this issue: Hoback Basin and northern Overthrust Belt 3-D interactive images: Landscapes and Wyoming State Geological Survey landslides Lance Cook, State Geologist The Blue Trail Slide Laramie, Wyoming July, 2002 Wyoming Geo-notes No. 74 July, 2002 Featured Articles Hoback Basin and northern Overthrust Belt . 2 3-D interactive images: Landscapes and landslides . 28 The Blue Trail Slide in the Snake River Canyon . 30 Contents Minerals update ...................................................... 1 Geologic hazards update .................................. 27 Overview............................................................... 1 Highway-affecting landslides of the Snake Calendar of upcoming events ............................ 5 River Canyon–Part III, Blue Trail Slide........ 30 Oil and gas update............................................... 6 Publications update .............................................. 34 Coal update......................................................... 13 New publications available from the Coalbed methane update.................................. 18 Wyoming State Geological Survey ............... 34 Industrial minerals and uranium update....... 19 Ordering information ........................................ 35 Metals and precious stones update ................. 22 Location maps of the Wyoming State Rock hound’s corner: Calcite and onyx .......... 23 Geological Survey ........................................... 36 Geologic mapping and hazards update ............ -

Bringing the Story of the Cheyenne People to the Children of Today Northern Cheyenne Social Studies Units Northern Cheyenne Curriculum Committee 2006

Indian Education for All Bringing the Story of the Cheyenne People to the Children of Today Northern Cheyenne Social Studies Units Northern Cheyenne Curriculum Committee 2006 Ready - to - Go Grant Elsie Arntzen, Superintendent • Montana Office of Public Instruction • www.opi.mt.gov LAME DEER SCHOOLS NORTHERN CHEYENNE SOCIAL STUDIES CURRICULUM TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction & Curriculum Framework ........................................................................3 Core Understandings & Learning Objectives ...............................................................8 Glossary for Lesson Content .......................................................................................17 Northern Cheyenne Recommended Grade Level Content ..........................................21 Northern Cheyenne Social Studies Model Lessons Grades 1-12 With Northern Cheyenne Content Resources .........................................................23 APPENDIX Pertinent Web Sites ....................................................................................................... 2 Protocol for Guest Speakers.......................................................................................... 3 Day of the Visit ............................................................................................................. 4 Chronology of Northern Cheyenne Government (Board Approved) .......................... 5 Amended Constitution & Bylaws of the Northern Cheyenne Tribe ............................ 9 Treaties with the Northern Cheyenne Tribe .............................................................. -

Action Research to Build the Capacity of Nyikina Indigenous Australians

Culturally sensitive and confidential material not to be reproduced without permission of the author. Action Research to Build the Capacity of Nyikina Indigenous Australians Anne Poelina Master of Arts (Indigenous Social Policy): The University of Technology, Sydney Master of Education (Research): Curtin University of Technology, WA Master of Public Health and Tropical Medicine: James Cook University, North Queensland Graduate Diploma in Education Studies (Aboriginal Education): Armidale College of Advanced Education (now University of New England), NSW Associate Diploma in Health Education: Western Australian College of Advanced Education (now Edith Cowan University) Registered Nurse: Western Australian School of Nursing A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of New England December 2008 Culturally sensitive and confidential material – not to be reproduced without permission of the author. Acknowledgements I am grateful to Dr David Plummer who was my principal supervisor in the early period of my study. David inspired me to continue learning and to think from multiple perspectives. I thank Dr Jeanne Madison, Head of School of Health who continued to encourage me when she took on the role of principal supervisor, following David’s international posting. I acknowledge Dr Myfanwy Maple, School of Health as a supervisor with new ideas and a structure that moved the writing of the study into its final format. I also appreciate the assistance of Dr Helen Edwards, School of Education who provided the technical guidance which enabled me to finalise this research project. To my friend and colleague, Colleen Hattersley, who provided invaluable editorial comment, all the while reinforcing in me the importance our collective narrative on Nyikina resilience and resourcefulness. -

National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form REGISTER

NFS Form 10-900-b OMB ^fo 1024-0018 (Jan 1987) F j United States Department of the Interior | National Park Service ^^ National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form REGISTER This form is for use in documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16), Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Type all entries. A. Name of Multiple Property Listing Pioneer Ranches/Farms in Fremont County, Wyoming, ca. 1865-1895_________ B. Associated Historic Contexts Ranching/Farming in Fremont County. Wyoming, ca. 1865-18Q5_____________ C. Geographical Data_____ Fremont County, Wyoming See continuation sheet D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirerjaeots set forth in 36 CFR Part 60 and the Secretary of the Interior's Standards for Planning and Evaluation. Signature of certifying official Date State or Federal agency and bureau I, hereby, certify that this multiple property documentation form has been approved by the National Register as a basis for evaluating related properties for listing in the National Register. Jjv Signature of the Keeper of the National Register Date E. Statement of Historic Contexts Discuss each historic context listed in Section B. -

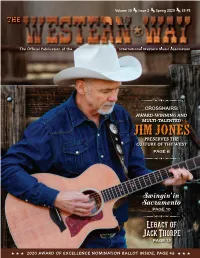

Spring 2020 $5.95 THE

Volume 30 Issue 2 Spring 2020 $5.95 THE The Offi cial Publication of the International Western Music Association CROSSHAIRS: AWARD-WINNING AND MULTI-TALENTED JIM JONES PRESERVES THE CULTURE OF THE WEST PAGE 6 Swingin’ in Sacramento PAGE 10 Legacy of Jack Thorpe PAGE 12 ★ ★ ★ 2020 AWARD OF EXCELLENCE NOMINATION BALLOT INSIDE, PAGE 46 ★ ★ ★ __WW Spring 2020_Cover.indd 1 3/18/20 7:32 PM __WW Spring 2020_Cover.indd 2 3/18/20 7:32 PM 2019 Instrumentalist of the Year Thank you IWMA for your love & support of my music! HaileySandoz.com 2020 WESTERN WRITERS OF AMERICA CONVENTION June 17-20, 2020 Rushmore Plaza Holiday Inn Rapid City, SD Tour to Spearfish and Deadwood PROGRAMMING ON LAKOTA CULTURE FEATURED SPEAKER Virginia Driving Hawk Sneve SESSIONS ON: Marketing, Editors and Agents, Fiction, Nonfiction, Old West Legends, Woman Suffrage and more. Visit www.westernwriters.org or contact wwa.moulton@gmail. for more info __WW Spring 2020_Interior.indd 1 3/18/20 7:26 PM FOUNDER Bill Wiley From The President... OFFICERS Robert Lorbeer, President Jerry Hall, Executive V.P. Robert’s Marvin O’Dell, V.P. Belinda Gail, Secretary Diana Raven, Treasurer Ramblings EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Marsha Short IWMA Board of Directors, herein after BOD, BOARD OF DIRECTORS meets several times each year; our Bylaws specify Richard Dollarhide that the BOD has to meet face to face for not less Juni Fisher Belinda Gail than 3 meetings each year. Jerry Hall The first meeting is usually in the late January/ Robert Lorbeer early February time frame, and this year we met Marvin O’Dell Robert Lorbeer Theresa O’Dell on February 4 and 5 in Sierra Vista, AZ.