Hong Kong in 1963–1964: Adventures of a Budding China Watcher Hong Kong Law Journal, Volume 47, Part 1 of 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Modern Hong Kong

Modern Hong Kong Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Asian History Modern Hong Kong Steve Tsang Subject: China, Hong Kong, Macao, and/or Taiwan Online Publication Date: Feb 2017 DOI: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190277727.013.280 Abstract and Keywords Hong Kong entered its modern era when it became a British overseas territory in 1841. In its early years as a Crown Colony, it suffered from corruption and racial segregation but grew rapidly as a free port that supported trade with China. It took about two decades before Hong Kong established a genuinely independent judiciary and introduced the Cadet Scheme to select and train senior officials, which dramatically improved the quality of governance. Until the Pacific War (1941–1945), the colonial government focused its attention and resources on the small expatriate community and largely left the overwhelming majority of the population, the Chinese community, to manage themselves, through voluntary organizations such as the Tung Wah Group of Hospitals. The 1940s was a watershed decade in Hong Kong’s history. The fall of Hong Kong and other European colonies to the Japanese at the start of the Pacific War shattered the myth of the superiority of white men and the invincibility of the British Empire. When the war ended the British realized that they could not restore the status quo ante. They thus put an end to racial segregation, removed the glass ceiling that prevented a Chinese person from becoming a Cadet or Administrative Officer or rising to become the Senior Member of the Legislative or the Executive Council, and looked into the possibility of introducing municipal self-government. -

Laws Governing Homosexual Conduct

THE LAW REFORM COMMISSION OF HONG KONG REPORT LAWS GOVERNING HOMOSEXUAL CONDUCT (TOPIC 2) LAWS GOVERNING HOMOSEXUAL CONDUCT WHEREAS : On 15 January 1980, His Excellency the Governor of Hong Kong Sir Murray MacLehose, GBE, KCMG, KCVO in Council directed the establishment of the Law Reform Commission of Hong Kong and appointed it to report upon such of the laws of Hong Kong as may be referred to it for consideration by the Attorney General and the Chief Justice; On 14 June 1980, the Honourable the Attorney General and the Honourable the Chief Justice referred to this Commission for consideration a Topic in the following terms : "Should the present laws governing homosexual conduct in Hong Kong be changed and, if so, in what way?" On 5 July 1980, the Commission appointed a Sub-committee to research, consider and then advise it upon aspects of the said matter; On 28 June 1982, the Sub-committee reported to the Commission, and the Commission considered the topic at meetings between July 1982 and April, 1983. We are agreed that the present laws governing homosexual conduct in Hong Kong should be changed, for reasons set out in our report; We have made in this report recommendations about the way in which laws should be changed; i NOW THEREFORE DO WE THE UNDERSIGNED MEMBERS OF THE LAW REFORM COMMISSION OF HONG KONG PRESENT OUR REPORT ON LAWS GOVERNING HOMOSEXUAL CONDUCT IN HONG KONG : Hon John Griffiths, QC Hon Sir Denys Roberts, KBE (Attorney General) (Chief Justice) (祈理士) (羅弼時) Hon G.P. Nazareth, OBE, QC Robert Allcock, Esq. -

1 December 1993 1141 OFFICIAL RECORD of PROCEEDINGS

HONG KONG LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL — 1 December 1993 1141 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 1 December 1993 The Council met at half-past Two o'clock PRESENT THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE JOHN JOSEPH SWAINE, C.B.E., LL.D., Q.C., J.P. THE CHIEF SECRETARY THE HONOURABLE MRS ANSON CHAN, C.B.E., J.P. THE FINANCIAL SECRETARY THE HONOURABLE NATHANIEL WILLIAM HAMISH MACLEOD, C.B.E., J.P. THE ATTORNEY GENERAL THE HONOURABLE JEREMY FELL MATHEWS, C.M.G., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALLEN LEE PENG-FEI, C.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS SELINA CHOW LIANG SHUK-YEE, O.B.E., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE DAVID LI KWOK-PO, O.B.E., LL.D., J.P. THE HONOURABLE NGAI SHIU-KIT, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE PANG CHUN-HOI, M.B.E. THE HONOURABLE SZETO WAH THE HONOURABLE ANDREW WONG WANG-FAT, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU WONG-FAT, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE RONALD JOSEPH ARCULLI, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MARTIN GILBERT BARROW, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS PEGGY LAM, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS MIRIAM LAU KIN-YEE, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU WAH-SUM, O.B.E., J.P. 1142 HONG KONG LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL — 1 December 1993 DR THE HONOURABLE LEONG CHE-HUNG, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE JAMES DAVID McGREGOR, O.B.E., I.S.O., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS ELSIE TU, C.B.E. THE HONOURABLE PETER WONG HONG-YUEN, O.B.E., J.P. -

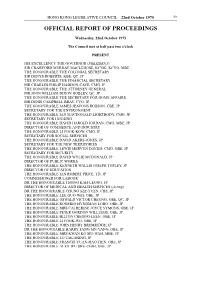

![OFFICIAL REPORT of PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 2Nd December 1970 the Council Met at Half Past Two O'clock [MR PRESIDENT in the Chair]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2949/official-report-of-proceedings-wednesday-2nd-december-1970-the-council-met-at-half-past-two-oclock-mr-president-in-the-chair-2542949.webp)

OFFICIAL REPORT of PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 2Nd December 1970 the Council Met at Half Past Two O'clock [MR PRESIDENT in the Chair]

HONG KONG LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL―2nd December 1970. 209 OFFICIAL REPORT OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 2nd December 1970 The Council met at half past Two o'clock [MR PRESIDENT in the Chair] PRESENT HIS EXCELLENCY THE ACTING GOVERNOR (PRESIDENT) SIR HUGH SELBY NORMAN-WALKER, KCMG, OBE, JP THE HONOURABLE THE COLONIAL SECRETARY (Acting) MR DAVID RONALD HOLMES, CMG, CBE, MC, ED, JP THE HONOURABLE THE ATTORNEY GENERAL (Acting) MR GRAHAM RUPERT SNEATH, QC, JP THE HONOURABLE THE SECRETARY FOR HOME AFFAIRS (Acting) MR DENIS CAMPBELL BRAY, JP THE HONOURABLE THE FINANCIAL SECRETARY SIR JOHN JAMES COWPERTHWAITE, KBE, CMG, JP THE HONOURABLE ROBERT MARSHALL HETHERINGTON, DFC, JP COMMISSIONER OF LABOUR THE HONOURABLE DAVID RICHARD WATSON ALEXANDER, MBE, JP DIRECTOR OF URBAN SERVICES THE HONOURABLE DONALD COLLIN CUMYN LUDDINGTON, JP DISTRICT COMMISSIONER, NEW TERRITORIES THE HONOURABLE JOHN CANNING, JP DIRECTOR OF EDUCATION DR THE HONOURABLE GERALD HUGH CHOA, JP DIRECTOR OF MEDICAL AND HEALTH SERVICES THE HONOURABLE PAUL TSUI KA-CHEUNG, OBE, JP COMMISSIONER FOR RESETTLEMENT THE HONOURABLE RICHARD CHARLES CLARKE, ISO, JP DIRECTOR OF PUBLIC WORKS (Acting) THE HONOURABLE ERNEST IRFON LEE, JP DIRECTOR OF COMMERCE AND INDUSTRY (Acting) THE HONOURABLE KAN YUET-KEUNG, CBE, JP THE HONOURABLE WOO PAK-CHUEN, OBE, JP THE HONOURABLE SZETO WAI, OBE, JP THE HONOURABLE WILFRED WONG SIEN-BING, OBE, JP THE HONOURABLE ELLEN LI SHU-PUI, OBE, JP THE HONOURABLE WILSON WANG TZE-SAM, JP THE HONOURABLE HERBERT JOHN CHARLES BROWNE, JP DR THE HONOURABLE CHUNG SZE-YUEN, OBE, JP THE HONOURABLE LEE QUO-WEI, OBE, JP THE HONOURABLE OSWALD VICTOR CHEUNG, QC, JP THE HONOURABLE GERALD MORDAUNT BROOME SALMON, JP THE HONOURABLE ANN TSE-KAI, OBE, JP THE HONOURABLE LO KWEE-SEONG, JP IN ATTENDANCE THE CLERK TO THE LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL MR RODERICK JOHN FRAMPTON 210 HONG KONG LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL―2nd December 1970. -

28 July 1982 1073

HONG KONG LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL―28 July 1982 1073 OFFICIAL REPORT OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 28 July 1982 The Council met at half past two o’clock PRESENT HIS EXCELLENCY THE ACTING GOVERNOR (PRESIDENT) THE HONOURABLE THE CHIEF SECRETARY SIR CHARLES PHILIP HADDON-CAVE, K.B.E., C.M.G., J.P. THE HONOURABLE THE FINANCIAL SECRETARY MR. JOHN HENRY BREMRIDGE, O.B.E. THE HONOURABLE THE ATTORNEY GENERAL MR. JOHN CALVERT GRIFFITHS, Q.C. THE HONOURABLE THE SECRETARY FOR HOME AFFAIRS (Acting) MR. DAVID AKERS-JONES, C.M.G., J.P. THE HONOURABLE DAVID GREGORY JEAFFRESON, C.B.E., J.P. SECRETARY FOR ECONOMIC SERVICES THE HONOURABLE ALAN JAMES SCOTT, C.B.E., J.P. SECRETARY FOR TRANSPORT THE HONOURABLE ERIC PETER HO, C.B.E., J.P. SECRETARY FOR SOCIAL SERVICES THE HONOURABLE JAMES NEIL HENDERSON, J.P. COMMISSIONER FOR LABOUR THE HONOURABLE JOHN MORRISON RIDDELL-SWAN, O.B.E., J.P. DIRECTOR OF AGRICULTURE AND FISHERIES THE HONOURABLE DONALD LIAO POON-HUAI, O.B.E., J.P. SECRETARY FOR HOUSING THE HONOURABLE GRAHAM BARNES, J.P. REGIONAL SECRETARY (HONG KONG AND KOWLOON), CITY AND NEW TERRITORIES ADMINISTRATION THE HONOURABLE COLVYN HUGH HAYE, J.P. SECRETARY FOR EDUCATION (Acting) DIRECTOR OF EDUCATION THE HONOURABLE IAN FRANCIS CLUNY MACPHERSON, J.P. SECRETARY FOR CITY AND NEW TERRITORIES ADMINISTRATION (Acting) REGIONAL SECRETARY (NEW TERRITORIES), CITY AND NEW TERRITORIES ADMINISTRATION THE HONOURABLE MRS. ANSON CHAN, J.P. DIRECTOR OF SOCIAL WELFARE (Acting) THE HONOURABLE CHAN NAI-KEONG, J.P. SECRETARY FOR LANDS AND WORKS (Acting) DR. THE HONOURABLE LAM SIM-FOOK, O.B.E., J.P. -

Biographies of Directors and Officers

Annual Report 2004 17 Qin Jia Yuan Media Services Company Limited BIOGRAPHIES OF DIRECTORS AND OFFICERS EXECUTIVE DIRECTORS Dr. LEUNG Anita Fung Yee Maria, aged 55, is the co-founder and the Chief Executive Officer of the Group. She is responsible for corporate planning, business development strategy and overall direction of the Group. She also participates in the provision of concepts and ideas for TV programme production. Dr. Leung holds a Doctorate degree (major in Chinese History) from The Chinese University of Hong Kong. She has more than 34 years’ experience in media industry in relation to TV programme production, public relations, advertising and marketing. Dr. Leung worked for a number of renowned companies in Hong Kong in senior management position, including Sun Hung Kai Securities Limited, the Hong Kong branch of Ogilvy & Mather Advertising (successor of Michael Stevenson Public Relations Company Ltd.) and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited (the “Stock Exchange”). Dr. Leung operated one of the first Hong Kong recruitment agencies which took the lead in introducing Filipino domestic helpers for families in Hong Kong during the period from late 70’s to mid 80’s. Dr. Leung is also a renowned novelist in both Hong Kong and the People’s Republic of China (the “PRC”) and has written more than 100 novels and books since 1989. In 1992, Dr. Leung was awarded the Writer of the Year 1991 Award by the Hong Kong Artist’s Guild and the Novelist of the Year 1992 Award awarded by the Urban Council of Hong Kong and the Artists Alliance. -

Governing Hong Kong ______

GOVERNING HONG KONG _______________________________________________________ AdministrativeAdministrative OcersOfficers from from the the NineteenthNineteenth Century Century toto thethe Handover Handover toto China, China, 1862-19971862–1997 Steve Tsang Hong Kong University Press 14/F Hing Wai Centre 7 Tin Wan Praya Road Aberdeen Hong Kong © Steve Tsang 2007 First published 2007 Reprinted 2008, 2010 ISBN 978-962-209-874-9 This edition published by Hong Kong University Press is available in Mainland China, Hong Kong, Macau, North and South Korea. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior written permission from the publisher. Secure On-line Ordering http://www.hkupress.org Printed and bound by The Green Pagoda Press Ltd., Hong Kong, China. From camera-ready copy edited and typeset by Oxford Publishing Services, Oxford. CONTENTS ___________________ Acronyms and Abbreviations vii Preface viii 1. Governance in a colonial society 1 Managing the expatriate community 3 Governing the local Chinese 6 Institutional inadequacies 9 2. The cadet scheme 13 Origins 13 From language cadets to bureaucratic high flyers 19 Impact on colonial administration 23 3. Benevolent paternalism 27 Learning about the Chinese 29 Life and work as a cadet 33 The making of an elite 43 4. Effects of the Pacific War 51 End of the colour bar 52 A new outlook 58 5. Expansion 67 From cadets to administrative officers 69 Ever expanding scope of government activities 72 The last of the old guard 75 Rapid growth and changes 84 Contents 6. Meeting the challenges of a Chinese community 87 Life and work of a modern district officer 87 The life and work of a CDO 94 Life and work at the secretariat 99 Life and work in departments 104 Fighting corruption 110 7. -

Appendix 1 - Table of Law Reform Agency Budgets

APPENDIX 1 - TABLE OF LAW REFORM AGENCY BUDGETS All budgets have been converted to sterling. Unless otherwise stated in the text, the exchange rate used is the rate applicable in August 1988, to the nearest £100 sterling. Most budgets were taken from the replies to question 8 of the questionnaire. The budgets of Vic toria, Westem Australia and Queensland were taken from LRC of Tasmania, Thirteenth Annual Report, transcript, p. 11. The letter 'x' in the "Period" column indicates that the period to which the budget applies is not known. AGENCY PERIOD AMOUNT £ STERLING I.Canada-Federal 1986-87 CAN$4,799,000 2,323,500 2.England and Wales 1986-87 £2.062,300 2,062.300 3. Australia • Federal X AUS$2,800.000 1.300.000 4.New Zealand 1988-89 NZ$2,800,000 1,120.000 S.Victoria (L.Reform Commission) 1986-87 AUS$l,600.000 740,800 6.Ontario X CANS 1,200,000 580,000 7.New South Wales X AUS$1,100,000 510,000 8.Louisiana 1987-88 US$650,138 380.000 9.Western Australia 1986-87 AUS$700,000 324.000 lO.California X US$525,000 308,800 ll.Ireland 1988 IR£310,000 267.800 12.Brilish Columbia X CAN$550.000 267.000 13.New Jersey X US$400,000 235,000 14.Manitoba X CAN$366,000 17.800 IS.Arkansas X US$271,356 160.000 (Appendix 1 is continued on the next page) Appendix 1 248 16.Quecnsland 1986-87 AUSS250.000 115,800 n.Connecticut (salaries only) X US$148,904 87,600 ^•Newfoundland X CANS 100.000 48,500 19.Tanzania 1987-88 T.Sh.5,200,000 46,400 2O.Tasmania 1986-87 AUSS93.00O 43,000 21.Sri Lanka X Rs. -

Official Report of Proceedings

HONG KONG LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL—22nd October 1975 59 OFFICIAL REPORT OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 22nd October 1975 The Council met at half past two o'clock PRESENT HIS EXCELLENCY THE GOVERNOR (PRESIDENT) SIR CRAWFORD MURRAY MACLEHOSE, KCMG, KCVO, MBE THE HONOURABLE THE COLONIAL SECRETARY SIR DENYS ROBERTS, KBE, QC, JP THE HONOURABLE THE FINANCIAL SECRETARY MR CHARLES PHILIP HADDON-CAVE, CMG, JP THE HONOURABLE THE ATTORNEY GENERAL MR JOHN WILLIAM DIXON HOBLEY, QC, JP THE HONOURABLE THE SECRETARY FOR HOME AFFAIRS MR DENIS CAMPBELL BRAY, CVO, JP THE HONOURABLE JAMES JEAVONS ROBSON, CBE, JP SECRETARY FOR THE ENVIRONMENT THE HONOURABLE IAN MACDONALD LIGHTBODY, CMG, JP SECRETARY FOR HOUSING THE HONOURABLE DAVID HAROLD JORDAN, CMG, MBE, JP DIRECTOR OF COMMERCE AND INDUSTRY THE HONOURABLE LI FOOK-KOW, CMG, JP SECRETARY FOR SOCIAL SERVICES THE HONOURABLE DAVID AKERS-JONES, JP SECRETARY FOR THE NEW TERRITORIES THE HONOURABLE LEWIS MERVYN DAVIES, CMG, OBE, JP SECRETARY FOR SECURITY THE HONOURABLE DAVID WYLIE MCDONALD, JP DIRECTOR OF PUBLIC WORKS THE HONOURABLE KENNETH WALLIS JOSEPH TOPLEY, JP DIRECTOR OF EDUCATION THE HONOURABLE IAN ROBERT PRICE, TD, JP COMMISSIONER FOR LABOUR DR THE HONOURABLE THONG KAH-LEONG, JP DIRECTOR OF MEDICAL AND HEALTH SERVICES (Acting) DR THE HONOURABLE CHUNG SZE-YUEN, CBE, JP THE HONOURABLE LEE QUO-WEI, OBE, JP THE HONOURABLE OSWALD VICTOR CHEUNG, OBE, QC, JP THE HONOURABLE ROGERIO HYNDMAN LOBO, OBE, JP THE HONOURABLE MRS CATHERINE JOYCE SYMONS, OBE, JP THE HONOURABLE PETER GORDON WILLIAMS, OBE, JP THE HONOURABLE HILTON CHEONG-LEEN, -

The Universities Service Centre for China Studies – Present at the Creation Draft, January 2015

Jerome A. Cohen The Universities Service Centre for China Studies – Present at the Creation Draft, January 2015. The Universities Service Centre for China Studies – Present at the Creation Jerome A. Cohen* For the benefit of our “revolutionary successors”, I submit this brief memoir on the origins of the Universities Service Centre for China Studies (USC or the Centre), on behalf of the handful of scholars who were its first beneficiaries. I regret that I cannot be with you in person but am confident that my distinguished colleague and friend, Professor Ezra Vogel, who was also “present at the creation”, can convey more of the atmosphere, aspirations and achievements associated with the Centre’s establishment and our early attempts to analyze developments in the “new China.” SETTLING INTO COLONIAL HONG KONG BEFORE THERE WAS A CENTRE TO HELP First, a few paragraphs about the mundane challenges that Hong Kong presented to most itinerant academics in that distant era. In the summer of 1963, without an organization such as the USC to offer assistance, it was difficult for a visiting scholar to set up shop in Hong Kong for a family of five and to find a place to carry out research on China. The fact that my area of interest was the Mainland’s criminal justice system, even then a very politically sensitive topic, did not make it any easier. Housing was plainly the most urgent requirement. We had no one to help us. I was a young American law school professor and had hoped to develop an academic affiliation for the year but at that time no Hong Kong university had established a law school. -

Official Report of Proceedings

HONG KONG LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL — 17th December 1975 309 OFFICIAL REPORT OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 17th December 1975 The Council met at half past two o'clock PRESENT HIS EXCELLENCY THE ACTING GOVERNOR (PRESIDENT) SIR DENYS ROBERTS, KBE, QC, JP THE HONOURABLE THE FINANCIAL SECRETARY (Acting) MR DEREK JOHN CLAREMONT JONES, JP THE HONOURABLE THE ATTORNEY GENERAL MR JOHN WILLIAM DIXON HOBLEY, QC, JP THE HONOURABLE THE SECRETARY FOR HOME AFFAIRS MR DENIS CAMPBELL BRAY, CVO, JP THE HONOURABLE JAMES JEAVONS ROBSON, CBE, JP SECRETARY FOR THE ENVIRONMENT DR THE HONOURABLE GERALD HUGH CHOA, CBE, JP DIRECTOR OF MEDICAL AND HEALTH SERVICES THE HONOURABLE IAN MACDONALD LIGHTBODY, CMG, JP SECRETARY FOR HOUSING THE HONOURABLE LI FOOK-KOW, CMG, JP SECRETARY FOR SOCIAL SERVICES THE HONOURABLE DAVID AKERS-JONES, JP SECRETARY FOR THE NEW TERRITORIES THE HONOURABLE LEWIS MERVYN DAVIES, CMG, OBE, JP SECRETARY FOR SECURITY THE HONOURABLE DAVID WYLIE McDONALD, JP DIRECTOR OF PUBLIC WORKS THE HONOURABLE KENNETH WALLIS JOSEPH TOPLEY, JP DIRECTOR OF EDUCATION THE HONOURABLE IAN ROBERT PRICE, TD, JP COMMISSIONER FOR LABOUR DR THE HONOURABLE CHUNG SZE-YUEN, CBE, JP THE HONOURABLE LEE QUO-WEI, OBE, JP THE HONOURABLE OSWALD VICTOR CHEUNG, OBE, QC, JP THE HONOURABLE ROGERIO HYNDMAN LOBO, OBE, JP THE HONOURABLE MRS CATHERINE JOYCE SYMONS, OBE, JP THE HONOURABLE JAMES WU MAN-HON, OBE, JP THE HONOURABLE HILTON CHEONG-LEEN, OBE, JP THE HONOURABLE LI FOOK-WO, OBE, JP THE HONOURABLE JOHN HENRY BREMRIDGE, JP DR THE HONOURABLE HARRY FANG SIN-YANG, OBE, JP THE HONOURABLE MRS -

Report on Laws on Insurance (Topic 9)

THE LAW REFORM COMMISSION OF HONG KONG REPORT ON LAWS ON INSURANCE (TOPIC 9) TERMS OF REFERENCE On 15 January 1982 the Honourable Attorney General and the Honourable Chief Justice referred to this Commission for consideration a topic in the following terms :- “ Laws on Insurance : (1) The present law permits an insurer to avoid his liability under the Policy if : (a) the insured, at the inception of the policy, failed to disclose or otherwise misrepresented a material fact; or (b) was in breach of the conditions of the policy without regard to whether the particular non-disclosure, misrepresentation or breach of condition played any part in the causation of, or had any relevance to, the accident in respect of which the claim is made. Should such law, and any other law related thereto, be changed, and if so in what way? (2) Whether any, and if so what, change is required in the laws governing the manner in which contracts of insurance are made (in particular the communication of the terms thereof to prospective policyholders) and including the activities of intermediaries such as brokers and agents, and whether there should be any regulation, and if so in what form, of such intermediaries." We have considered the topic and now present our report. ii Now therefore do we the following members of the Law Reform Commission of Hong Kong present our report on Laws on Insurance Hon Michael Thomas CMG QC (Attorney General) Hon Sir Denys Roberts KBE (Chief Justice) Mr J J O'Grady (Law Draftsman) Mr Robert Allcock Mr Graham Cheng JP Hon Mr Justice