LIII December 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Modern Hong Kong

Modern Hong Kong Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Asian History Modern Hong Kong Steve Tsang Subject: China, Hong Kong, Macao, and/or Taiwan Online Publication Date: Feb 2017 DOI: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190277727.013.280 Abstract and Keywords Hong Kong entered its modern era when it became a British overseas territory in 1841. In its early years as a Crown Colony, it suffered from corruption and racial segregation but grew rapidly as a free port that supported trade with China. It took about two decades before Hong Kong established a genuinely independent judiciary and introduced the Cadet Scheme to select and train senior officials, which dramatically improved the quality of governance. Until the Pacific War (1941–1945), the colonial government focused its attention and resources on the small expatriate community and largely left the overwhelming majority of the population, the Chinese community, to manage themselves, through voluntary organizations such as the Tung Wah Group of Hospitals. The 1940s was a watershed decade in Hong Kong’s history. The fall of Hong Kong and other European colonies to the Japanese at the start of the Pacific War shattered the myth of the superiority of white men and the invincibility of the British Empire. When the war ended the British realized that they could not restore the status quo ante. They thus put an end to racial segregation, removed the glass ceiling that prevented a Chinese person from becoming a Cadet or Administrative Officer or rising to become the Senior Member of the Legislative or the Executive Council, and looked into the possibility of introducing municipal self-government. -

Race for Distinction a Social History of Private Members' Clubs in Colonial Kenya

Race for Distinction A Social History of Private Members' Clubs in Colonial Kenya Dominique Connan Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of History and Civilization of the European University Institute Florence, 09 December 2015 European University Institute Department of History and Civilization Race for Distinction A Social History of Private Members' Clubs in Colonial Kenya Dominique Connan Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of History and Civilization of the European University Institute Examining Board Prof. Stephen Smith (EUI Supervisor) Prof. Laura Lee Downs, EUI Prof. Romain Bertrand, Sciences Po Prof. Daniel Branch, Warwick University © Connan, 2015 No part of this thesis may be copied, reproduced or transmitted without prior permission of the author Race for Distinction. A Social History of Private Members’ Clubs in Colonial Kenya This thesis explores the institutional legacy of colonialism through the history of private members clubs in Kenya. In this colony, clubs developed as institutions which were crucial in assimilating Europeans to a race-based, ruling community. Funded and managed by a settler elite of British aristocrats and officers, clubs institutionalized European unity. This was fostered by the rivalry of Asian migrants, whose claims for respectability and equal rights accelerated settlers' cohesion along both political and cultural lines. Thanks to a very bureaucratic apparatus, clubs smoothed European class differences; they fostered a peculiar style of sociability, unique to the colonial context. Clubs were seen by Europeans as institutions which epitomized the virtues of British civilization against native customs. In the mid-1940s, a group of European liberals thought that opening a multi-racial club in Nairobi would expose educated Africans to the refinements of such sociability. -

Focus on South Africa

Focus on South Africa africanhuntinggazette.com 1 Volume 19 • Issue 43 Hunting the great continent of Africa Summer 2014 2 africanhuntinggazette.com africanhuntinggazette.com 3 Contents KIMBER MOUNTAIN RIFLES. The springbok is the only gazelle species occurring Brooke’s Editorial Unequaled accuracy, dependability & light weight. in southern Africa, My Personal Proust Questionnaire 7 which has an estimated population of 500,000 to 800,000 animals, News & Letters mostly on private game An Ode to the African Hunting Gazette! By Robert von Reitnauer 8 ranches in South Africa, Botswana and Namibia. In Response to Article on Wingshooting in South Africa (AHG 19.2) Photo © Adrian Purdon By André van der Westhuizen 10 Regarding the Lee-Enfield By Stefan Serlachius 11 • Published quarterly, a quality journal presenting Announcement: Winner of the CZ 550 Magnum Lux 12 all aspects of hunting available in Africa. Fan Letter from South African Abroad By Carel Nolte 12 • The traditions and tales, the professional hunters of today, and the legends of yesteryear. On the Subject of Rhino Images in AHG Volume 19, Issue 2 By Duncan Nebbe 12 • Reporting on the places to go, the sport available and all the equipment to use. Hunters Do Good: Zimbabwe • Examining the challenges of managing wildlife Rifa Camp – An International Treasure? By Robert Deitz 14 as a sustainable resource and the relationship between Africa’s game and its people. Gear & Gadgets Publisher & Editor-in-Chief Barnes Bullets – 25th Anniversary of the X-Bullet 16 Richard Lendrum [email protected] Technoframes Domotic Display 16 Ruger Hawkeye African Bolt-action Rifle 17 Editor – Brooke ChilversLubin Meopta’s MeoStar R2 1-6x24 RD 17 [email protected] John Morris Safari Photography 18 Managing Editor – Esther Sibanda DVD Review: “Preparing Yourself for Stopping the Charge!” The lightest production hunting ri es ever o ered, [email protected] By Four Eyes 20 Mountain Ascent™ (top) and Montana™ models weigh as little as 4 pounds, 13 ounces. -

Lance Corporal J. P. HARMAN, V.C

2019 www.BritishMilitaryHistory.co.uk Author: Robert PALMER The Cross of Sacrifice Imphal War Cemetery A CONCISE BIOGRAPHY OF: LANCE CORPORAL J. P. HARMAN, V.C. (OF LUNDY) A concise biography of Lance Corporal John Pennington HARMAN, V.C., a soldier in the British Army between 1940 and 1944, who was awarded posthumously the Victoria Cross for gallantry during the Siege of Kohima. In addition, a biography of Sergeant Stanley James TACON, who was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal in the same action. Copyright ©www.BritishMilitaryHistory.co.uk (2019) 13 October 2019 [LANCE CORPORAL J. P. HARMAN, V.C.] A Concise Biography of Lance Corporal J. P. HARMAN, V.C. Version: 4_4 Dated: 13 October 2019 ISBN: Not yet allocated. All rights reserved. No part of the publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means including; electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, scanning without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Author: Robert PALMER, M.A. (copyright held by author) Assisted By: Stephen HEAL Published privately by: The Author – Publishing as: www.BritishMilitaryHistory.co.uk The Author wishes to extend his grateful thanks to Mr. Bob STREET, author of: ‘We Fought at Kohima’ for permission to use three maps from his book. In addition, to Mr Bob COOK, Curator at the Kohima Museum, Imphal Barracks, York for his support in preparing this booklet, and to the TACON family for supplying information and photographs about Stanley TACON. 1 13 October 2019 [LANCE CORPORAL J. P. HARMAN, V.C.] Contents Pages Introduction 3 Early Life and Lundy 4 – 5 The Second World War – Jack Enlists 6 HARMAN Joins the Royal West Kents 7 – 8 Kohima 9 – 19 Stanley James TACON 20 – 26 Epilogue 27 Bibliography and Sources 28 2 13 October 2019 [LANCE CORPORAL J. -

Laws Governing Homosexual Conduct

THE LAW REFORM COMMISSION OF HONG KONG REPORT LAWS GOVERNING HOMOSEXUAL CONDUCT (TOPIC 2) LAWS GOVERNING HOMOSEXUAL CONDUCT WHEREAS : On 15 January 1980, His Excellency the Governor of Hong Kong Sir Murray MacLehose, GBE, KCMG, KCVO in Council directed the establishment of the Law Reform Commission of Hong Kong and appointed it to report upon such of the laws of Hong Kong as may be referred to it for consideration by the Attorney General and the Chief Justice; On 14 June 1980, the Honourable the Attorney General and the Honourable the Chief Justice referred to this Commission for consideration a Topic in the following terms : "Should the present laws governing homosexual conduct in Hong Kong be changed and, if so, in what way?" On 5 July 1980, the Commission appointed a Sub-committee to research, consider and then advise it upon aspects of the said matter; On 28 June 1982, the Sub-committee reported to the Commission, and the Commission considered the topic at meetings between July 1982 and April, 1983. We are agreed that the present laws governing homosexual conduct in Hong Kong should be changed, for reasons set out in our report; We have made in this report recommendations about the way in which laws should be changed; i NOW THEREFORE DO WE THE UNDERSIGNED MEMBERS OF THE LAW REFORM COMMISSION OF HONG KONG PRESENT OUR REPORT ON LAWS GOVERNING HOMOSEXUAL CONDUCT IN HONG KONG : Hon John Griffiths, QC Hon Sir Denys Roberts, KBE (Attorney General) (Chief Justice) (祈理士) (羅弼時) Hon G.P. Nazareth, OBE, QC Robert Allcock, Esq. -

![[1(!] J:!Ljj Oolj0 £Ffilli1\1 GJ1\7Lfl Ru =RJ ~ a CJ;H 00 Jli!\CI'li!\[ID () ~ Edi.To1: Ann Westcott, Friendship, Guineaford, Barnstaple, N.Devon EX3 1 4EA](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0070/1-j-ljj-oolj0-%C2%A3ffilli1-1-gj1-7lfl-ru-rj-a-cj-h-00-jli-cili-id-edi-to1-ann-westcott-friendship-guineaford-barnstaple-n-devon-ex3-1-4ea-2120070.webp)

[1(!] J:!Ljj Oolj0 £Ffilli1\1 GJ1\7Lfl Ru =RJ ~ a CJ;H 00 Jli!\CI'li!\[ID () ~ Edi.To1: Ann Westcott, Friendship, Guineaford, Barnstaple, N.Devon EX3 1 4EA

[1(!] J:!lJJ OOlJ0 £ffilli1\1 GJ1\7lFl ru =RJ ~ a CJ;h 00 Jli!\CI'li!\[ID () ~ Edi.to1: Ann Westcott, Friendship, Guineaford, Barnstaple, N.Devon EX3 1 4EA. Telephone (027 1) 42259 EDITORIAL Abbreviations: WMN - Western Morning News: NDJ - North Devon Journal: NDA - North Devon Advertiser. WORKING PARTIES 1994 John Morgan has decided to step down as co - organiser of LFS working parties as from the AGM and we would like to thank him for all his hard work. We have, therefore, decided that this will provide an opportunity to streamline the organisation of working parties. Old Light West is now available for use by volunteers for most weeks throughout the year and the Warden, Andrew Gibson, is keen to utilise it to the full. So, we effectively have the opportunity to supply him with small groups of volunteers for a large part of the year and you can decide when you would like to take part. Numbers will be limited to four per week, allocated on a first come first served basis, so the sooner you contact me with your preferred dates the more likely they are to be available. The LFS also have the option of having larger groups of volunteers (maximum 10) staying in Quarters for the weeks 18th-26th March and 1st-8th October. If there is insufficient interest in these weeks to warrant retaining these bookings Old Light West should be available for a 4 person working party. The Field Society make a contribution of £24 per person which will cover your boat fare and a proportion of your food. -

1 December 1993 1141 OFFICIAL RECORD of PROCEEDINGS

HONG KONG LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL — 1 December 1993 1141 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 1 December 1993 The Council met at half-past Two o'clock PRESENT THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE JOHN JOSEPH SWAINE, C.B.E., LL.D., Q.C., J.P. THE CHIEF SECRETARY THE HONOURABLE MRS ANSON CHAN, C.B.E., J.P. THE FINANCIAL SECRETARY THE HONOURABLE NATHANIEL WILLIAM HAMISH MACLEOD, C.B.E., J.P. THE ATTORNEY GENERAL THE HONOURABLE JEREMY FELL MATHEWS, C.M.G., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALLEN LEE PENG-FEI, C.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS SELINA CHOW LIANG SHUK-YEE, O.B.E., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE DAVID LI KWOK-PO, O.B.E., LL.D., J.P. THE HONOURABLE NGAI SHIU-KIT, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE PANG CHUN-HOI, M.B.E. THE HONOURABLE SZETO WAH THE HONOURABLE ANDREW WONG WANG-FAT, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU WONG-FAT, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE RONALD JOSEPH ARCULLI, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MARTIN GILBERT BARROW, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS PEGGY LAM, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS MIRIAM LAU KIN-YEE, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU WAH-SUM, O.B.E., J.P. 1142 HONG KONG LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL — 1 December 1993 DR THE HONOURABLE LEONG CHE-HUNG, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE JAMES DAVID McGREGOR, O.B.E., I.S.O., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS ELSIE TU, C.B.E. THE HONOURABLE PETER WONG HONG-YUEN, O.B.E., J.P. -

![OFFICIAL REPORT of PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 2Nd December 1970 the Council Met at Half Past Two O'clock [MR PRESIDENT in the Chair]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2949/official-report-of-proceedings-wednesday-2nd-december-1970-the-council-met-at-half-past-two-oclock-mr-president-in-the-chair-2542949.webp)

OFFICIAL REPORT of PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 2Nd December 1970 the Council Met at Half Past Two O'clock [MR PRESIDENT in the Chair]

HONG KONG LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL―2nd December 1970. 209 OFFICIAL REPORT OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 2nd December 1970 The Council met at half past Two o'clock [MR PRESIDENT in the Chair] PRESENT HIS EXCELLENCY THE ACTING GOVERNOR (PRESIDENT) SIR HUGH SELBY NORMAN-WALKER, KCMG, OBE, JP THE HONOURABLE THE COLONIAL SECRETARY (Acting) MR DAVID RONALD HOLMES, CMG, CBE, MC, ED, JP THE HONOURABLE THE ATTORNEY GENERAL (Acting) MR GRAHAM RUPERT SNEATH, QC, JP THE HONOURABLE THE SECRETARY FOR HOME AFFAIRS (Acting) MR DENIS CAMPBELL BRAY, JP THE HONOURABLE THE FINANCIAL SECRETARY SIR JOHN JAMES COWPERTHWAITE, KBE, CMG, JP THE HONOURABLE ROBERT MARSHALL HETHERINGTON, DFC, JP COMMISSIONER OF LABOUR THE HONOURABLE DAVID RICHARD WATSON ALEXANDER, MBE, JP DIRECTOR OF URBAN SERVICES THE HONOURABLE DONALD COLLIN CUMYN LUDDINGTON, JP DISTRICT COMMISSIONER, NEW TERRITORIES THE HONOURABLE JOHN CANNING, JP DIRECTOR OF EDUCATION DR THE HONOURABLE GERALD HUGH CHOA, JP DIRECTOR OF MEDICAL AND HEALTH SERVICES THE HONOURABLE PAUL TSUI KA-CHEUNG, OBE, JP COMMISSIONER FOR RESETTLEMENT THE HONOURABLE RICHARD CHARLES CLARKE, ISO, JP DIRECTOR OF PUBLIC WORKS (Acting) THE HONOURABLE ERNEST IRFON LEE, JP DIRECTOR OF COMMERCE AND INDUSTRY (Acting) THE HONOURABLE KAN YUET-KEUNG, CBE, JP THE HONOURABLE WOO PAK-CHUEN, OBE, JP THE HONOURABLE SZETO WAI, OBE, JP THE HONOURABLE WILFRED WONG SIEN-BING, OBE, JP THE HONOURABLE ELLEN LI SHU-PUI, OBE, JP THE HONOURABLE WILSON WANG TZE-SAM, JP THE HONOURABLE HERBERT JOHN CHARLES BROWNE, JP DR THE HONOURABLE CHUNG SZE-YUEN, OBE, JP THE HONOURABLE LEE QUO-WEI, OBE, JP THE HONOURABLE OSWALD VICTOR CHEUNG, QC, JP THE HONOURABLE GERALD MORDAUNT BROOME SALMON, JP THE HONOURABLE ANN TSE-KAI, OBE, JP THE HONOURABLE LO KWEE-SEONG, JP IN ATTENDANCE THE CLERK TO THE LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL MR RODERICK JOHN FRAMPTON 210 HONG KONG LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL―2nd December 1970. -

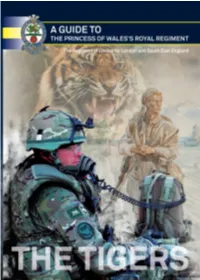

Guide to the Regiment Journal 2015

3 Her Majesty Queen Margrethe II of Denmark THE COLONEL-IN-CHIEF Contents PART I A Brief History Page 2 PART II The Regiment Today Page 33 PART III Regimental Information Page 46 Our Regiment, ‘The Tigers’, has I hope that you enjoy reading the now ‘come of age’, passed its Third Edition of this unique history twenty-first birthday and forged and thank the author, Colonel For further information its own modern identity based on Patrick Crowley, for updating the on the PWRR go to: recent operational experiences in content. I commend this excellent www.army.mod. Iraq and Afghanistan and its well- guide to our fine Regiment. uk/infantry/ known professionalism. Our long regiments/23994 heritage, explained in this Guide, Signed makes us proud to be the most New Virtual Museum web site: senior English Regiment of the www.armytigers.com Line and the Regiment of choice in London and the South East. If you are connected with the counties of Surrey, Kent, Sussex, Hampshire and the Isle of Wight, Middlesex and the Channel Islands, we are your regiment. We take a fierce pride Brigadier Richard Dennis OBE in our close connections with the The Colonel of The Regiment south of England where we recruit our soldiers and our PWRR Family consists of cadets, regular and reserve soldiers, veterans and their loved ones. In this Regiment, we celebrate the traditional virtues of courage, self-discipline and loyalty to our comrades and we take particular pride in the achievements of our junior ranks, like Sergeant Johnson Beharry, who won the Victoria Cross for his bravery under fire in Iraq. -

28 July 1982 1073

HONG KONG LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL―28 July 1982 1073 OFFICIAL REPORT OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 28 July 1982 The Council met at half past two o’clock PRESENT HIS EXCELLENCY THE ACTING GOVERNOR (PRESIDENT) THE HONOURABLE THE CHIEF SECRETARY SIR CHARLES PHILIP HADDON-CAVE, K.B.E., C.M.G., J.P. THE HONOURABLE THE FINANCIAL SECRETARY MR. JOHN HENRY BREMRIDGE, O.B.E. THE HONOURABLE THE ATTORNEY GENERAL MR. JOHN CALVERT GRIFFITHS, Q.C. THE HONOURABLE THE SECRETARY FOR HOME AFFAIRS (Acting) MR. DAVID AKERS-JONES, C.M.G., J.P. THE HONOURABLE DAVID GREGORY JEAFFRESON, C.B.E., J.P. SECRETARY FOR ECONOMIC SERVICES THE HONOURABLE ALAN JAMES SCOTT, C.B.E., J.P. SECRETARY FOR TRANSPORT THE HONOURABLE ERIC PETER HO, C.B.E., J.P. SECRETARY FOR SOCIAL SERVICES THE HONOURABLE JAMES NEIL HENDERSON, J.P. COMMISSIONER FOR LABOUR THE HONOURABLE JOHN MORRISON RIDDELL-SWAN, O.B.E., J.P. DIRECTOR OF AGRICULTURE AND FISHERIES THE HONOURABLE DONALD LIAO POON-HUAI, O.B.E., J.P. SECRETARY FOR HOUSING THE HONOURABLE GRAHAM BARNES, J.P. REGIONAL SECRETARY (HONG KONG AND KOWLOON), CITY AND NEW TERRITORIES ADMINISTRATION THE HONOURABLE COLVYN HUGH HAYE, J.P. SECRETARY FOR EDUCATION (Acting) DIRECTOR OF EDUCATION THE HONOURABLE IAN FRANCIS CLUNY MACPHERSON, J.P. SECRETARY FOR CITY AND NEW TERRITORIES ADMINISTRATION (Acting) REGIONAL SECRETARY (NEW TERRITORIES), CITY AND NEW TERRITORIES ADMINISTRATION THE HONOURABLE MRS. ANSON CHAN, J.P. DIRECTOR OF SOCIAL WELFARE (Acting) THE HONOURABLE CHAN NAI-KEONG, J.P. SECRETARY FOR LANDS AND WORKS (Acting) DR. THE HONOURABLE LAM SIM-FOOK, O.B.E., J.P. -

Horn of the Hunter

HORN OF THE HUNTER RR_HOH_reprint_book.indb 1 9/18/2012 11:16:12 AM Books by Robert C. Ruark HORN OF THE HUNTER GRENADINE’S SPAWN ONE FOR THE ROAD I DIDN’T KNOW IT WAS LOADED GRENADINE ETCHING RR_HOH_reprint_book.indb 2 9/18/2012 11:16:12 AM HORN OF THE HUNTER Robert C. Ruark With 32 Drawings by the Author and 32 Pages of Photographs Safari Press Inc. RR_HOH_reprint_book.indb 3 9/18/2012 11:16:13 AM DEDICATION This book is for Harry Selby of Nanyuki, Kenya and for our good friends Juma, Kidogo, Adem, Chabani, Chalo, Katunga, Ali, Karioki, Chege, Mala, Gitau, Gathiru, Kaluku, and Kibiriti, all good men of assorted tribes RR_HOH_reprint_book.indb 5 9/18/2012 11:16:13 AM Author’s Note This is a book about Africa in which I have tried to avoid most of the foolishness, personal heroism, and general exaggeration that usually attend works of this sort. It is a book important only to the writer and has no sociological significance whatsoever. RR_HOH_reprint_book.indb 7 9/18/2012 11:16:13 AM HORN OF THE HUNTER RR_HOH_reprint_book.indb 9 9/18/2012 11:16:13 AM RR_HOH_reprint_book.indb 10 9/18/2012 11:16:13 AM Chapter 1 T WAS very late the first day out of Nairobi when Harry turned the jeep off the dim track he was following through Ithe high, dusty grass and veered her toward a black jagged- ness of trees. The moon was rising high over a forlorn hill, and it had begun to turn nasty cold. -

Battle of Kohima, the Debt They Owe to Their Forebears, and the Inspiration That North East India Can Be Derived from Their Stories

261670_kohima_cover 1/4/04 11:29 Page 1 SECOND WORLD WAR TH ‘A nation that forgets its past has no future’. These words by Winston Churchill could not be more apt to describe the purpose of this series of booklets, of which this is the first. 60ANNIVERSARY These booklets commemorate various Second World War actions, and aim not only to remember and commemorate those who fought and died, but also to remind future generations of The Battle of Kohima, the debt they owe to their forebears, and the inspiration that North East India can be derived from their stories. 4 April – 22 June 1944 They will help those growing up now to be aware of the veterans’ sacrifices, and of the contributions they made to our security and to the way of life we enjoy today. ‘The turning point in the war with Japan’ 261670_kohima_cover 1/4/04 11:30 Page 3 The Ridge Kohima showing the main landmarks and the location of principal regiments. KOHIMA, THE CAPITAL OF NAGALAND IN THE NORTH EAST OF INDIA PAKISTAN DELHI BURMA INDIA KOLKATA Acknowledgements This booklet has been produced with the help of: BHUTAN Commonwealth War Graves Commission Confederation of British Service and Ex-Service Organisations (COBSEO) INDIA Department for Education and Skills Dimapur• Imperial War Museum •Kohima Major G Graham MC & Bar •Imphal New Opportunities Fund BANGLADESH Royal Military Academy Sandhurst BURMA The Burma Star Association DHAKA• KEY FACTS The Royal British Legion Remembrance Travel • The Victoria Cross and George Cross Association KOLKATA Kohima is: Veterans Agency • 5000 feet above sea level • 40 miles from Dimapur Photography All photography reproduced with the permission of the Imperial War Museum, Commonwealth War Graves • 80 miles from Imphal Commission and HMSO.