Is Comment Free? Ethical, Editorial and Political Problems of Moderating Online News

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Swedish General Election 2014 and the Representation of Women

Research and Information Service Research Paper 1 October 2014 Michael Potter The Swedish General Election 2014 and the Representation of Women NIAR 496-14 This paper reviews the Swedish general election of September 2014 from the perspective of the representation of women in politics. Paper 93/14 01 October 2014 Research and Information Service briefings are compiled for the benefit of MLAs and their support staff. Authors are available to discuss the contents of these papers with Members and their staff but cannot advise members of the general public. We do, however, welcome written evidence that relates to our papers and this should be sent to the Research and Information Service, Northern Ireland Assembly, Room 139, Parliament Buildings, Belfast BT4 3XX or e-mailed to [email protected] NIAR 496-014 Research Paper Key Points This paper seeks to explain the relatively high proportion of female political representatives in Sweden (45% in national and 43% in local legislatures) through analysis of the general election to the Swedish parliament (Riksdag) on 14 September 2014. Some contributory factors to consider are as follows: Context – Sweden has a range of provisions to facilitate women’s participation in wider society and to promote gender equality, for example: o Equality mainstreaming in government policy, including in budgets o Relatively generous parental leave, part of which must be taken by the second parent o Public childcare provision o Legislation considered conducive to the protection and autonomy of women o Statutory -

World Trademark Review's 50 Market Shapers

Feature By Trevor Little World Trademark Review’s 50 market shapers To mark World Trademark Review’s 50th edition, we on the basis of their daily work, but rather for their contributions identify 50 of the people, companies, cases and big- to particular debates (after all, if you are seeking potential legal picture issues that have defined the market on which partners, we offer the World Trademark Review 1000 – The World’s Leading Trademark Professionals for just that purpose). The list is we have been reporting for the last eight years presented alphabetically and is therefore ranked in no particular order; but it does provide a snapshot of the industry in which we all operate. Before we reveal the 50, it is important to acknowledge the single biggest influence on our evolution to date: you. Since World Trademark Review first hit subscribers’ desks in 2006, Without the loyalty of our subscribers, the World Trademark many aspects of the trademark world have changed beyond Review platform would not be where it is today, and you have measure. However, peruse that first issue and what instantly stands been integral to every step that we have taken along the way. out is how much remains familiar. The cover story focused on And I say ‘platform’ rather than ‘magazine’ quite deliberately. the fight between Anheuser-Busch and Bude jovický Budvar over Although the inaugural issue of World Trademark Review was the Budweiser brand – a battle that would rage on for a further published in April 2006, we can trace the origins of the title back eight years. -

FAIFE Newsletter

Issue 5: July 2012 FAIFE Newsletter Message from the Chair………………….…..p.1 FAIFE Speaker´s corner at WLIC……….….p. 2 New Spotlights for you……………………….p. 3 The newsletter of the International Federation of Library Associations’ IFLA Code of Ethics for Librarians in its final Committee on Freedom of Access to stages …………………………………………….….p. 3 Information and Freedom of FAIFE Books Club begins discussion of Ray Expression Bradbury´s “Fahrenheit 451”………………p. 4 Message from the Chair Kai Ekholm . Maker's mark 1) The successful FAIFE Advent calendar Panu Somerma, Entresse library 2) FAIFE Book Club Jonathan Kelley, ALA 3) ALA and most banned books in USA 2011-2 Barbara Jones Dear Faifeans! . Promoting CLM/FAIFE session / I hope this newsletter reaches you in good Päivikki Karhula health and spirit. We are happy to announce our program in Helsinki and . Promoting Speaker's corner / Kai invite you to join us. Your attendance is Ekholm highly appreciated. Secondly we invite you to FAIFE/CLM We are hoping to see you all in Helsinki joint session on Wednesday 15th August and at our sessions, starting on Sunday 9.30 – 12.45 around topics of copyright, 12th August 13.45 – 15.45 after Opening privacy and internet censorship and session. data surveillance. Our theme is as usual, a cheeky one MASTER OF CONTENTS OR HOW TO WIN SLEEPWALKING INTO A CONTROL THE BATTLE OVER FREEDOM IN SOCIETY? CYBERSPACE, 15th August 9.30 – 12.45 in Session Room 1 You will meet the following speakers and themes: 9.30-9.50 Privatization of cyberspace - case Google, Siva Vaidhyanathan, Media . -

Piracy and the Politics of Social Media

social sciences $€ £ ¥ Article Piracy and the Politics of Social Media Martin Fredriksson Almqvist Department for Culture Studies, Linköping University, 601 74 Norrköping, Sweden; [email protected]; Tel.: +46-11-363-492 Academic Editor: Terri Towner Received: 13 June 2016; Accepted: 20 July 2016; Published: 5 August 2016 Abstract: Since the 1990s, the understanding of how and where politics are made has changed radically. Scholars such as Ulrich Beck and Maria Bakardjieva have discussed how political agency is enacted outside of conventional party organizations, and political struggles increasingly focus on single issues. Over the past two decades, this transformation of politics has become common knowledge, not only in academic research but also in the general political discourse. Recently, the proliferation of digital activism and the political use of social media are often understood to enforce these tendencies. This article analyzes the Pirate Party in relation to these theories, relying on almost 30 interviews with active Pirate Party members from different parts of the world. The Pirate Party was initially formed in 2006, focusing on copyright, piracy, and digital privacy. Over the years, it has developed into a more general democracy movement, with an interest in a wider range of issues. This article analyzes how the party’s initial focus on information politics and social media connects to a wider range of political issues and to other social movements, such as Arab Spring protests and Occupy Wall Street. Finally, it discusses how this challenges the understanding of information politics as a single issue agenda. Keywords: piracy; Pirate Party; political mobilization; political parties; information politics; social media; activism 1. -

Julian Assange by Swedish Authorities

Assange & Sweden Miscellaneous Information: Part 5 Part 5: 1 July 2012 – 27 October 2012 This is a somewhat random collection of news clippings and other items relating to accusations of sexual misconduct that have been made against Julian Assange by Swedish authorities. Much of the material is in Swedish, but I believe that at least half is in English. The quality and reliability of the various items vary widely. In some places I have added clarifications, warnings, etc. [in italics, within square brackets and initialed--A.B.]. But there is nothing systematic about that, either, and everything in this document should be interpreted with due caution. Questions and comments regarding any of the information included here are welcome and may be addressed to me via e-mail at: [email protected] – Al Burke Nordic News Network Links to other parts of the series Documents in PDF format Require Adobe Reader or similar program Part 1: 14 August 2010 – 16 December 2010 www.nnn.se/nordic/assange/docs/case1.pdf Part 2: 17 December 2011 – 17 February 2011 www.nnn.se/nordic/assange/docs/case2.pdf Part 3: 20 February 2011 – 17 July 2011 www.nnn.se/nordic/assange/docs/case3.pdf Part 4: 8 August 2011 – 30 June 2012 www.nnn.se/nordic/assange/docs/case3.pdf For more and better-organized information: www.nnn.se/nordic/assange.htm How Julian Assange's private life helped conceal the real triumph of WikiLeaks Without the access to the US secret cables, the world would have no insight into how their governments behave Patrick Cockburn The Independent 1 July 2012 As Julian Assange evades arrest by taking refuge in the Ecuadorian embassy in Knightsbridge to escape extradition to Sweden, and possibly the US, British com- mentators have targeted him with shrill abuse. -

HACKERS EN POLITIQUE Politisation Du Cyberespace Et Hacktivisme

AIX-MARSEILLE UNIVERSITÉ INSTITUT D’ÉTUDES POLITIQUES D’AIX-EN-PROVENCE MÉMOIRE pour l’obtention du Diplôme HACKERS EN POLITIQUE Politisation du cyberespace et hacktivisme Par Madame Sophie ANDRIOL Mémoire réalisé sous la direction de Madame Stéphanie DECHEZELLES Année universitaire 2013-2014 L’IEP n’entend donner aucune approbation ou improbation aux opinions émises dans ce mémoire. Ces opinions doivent être considérées comme propres à leur auteur. MOTS CLEFS Hackers – Internet – Politique - Politisation Communauté – Mouvement social – Mobilisations Hacking – Hacktivisme – Activisme RÉSUMÉ Pirates des temps modernes ou corsaires du cyberespace ? Au-delà de l’anonymat cher aux hackers, ce travail de recherche sociologique a pour ambition de décrypter les modalités de leur entrée en politique. L’analyse des trajectoires individuelles des hackers et du spectre de leurs engagements permet de prendre la mesure de la politisation du mouvement et d’explorer ses modalités, du hacktivisme anonyme venant en aide aux populations des révolutions arabes, au militantisme partisan en Europe. Ainsi, au travers de l’étude des structures et des contextes qui portent le mouvement ou le condamnent, nous éclairons ici les dynamiques d’un processus de politisation qui ont fait d’un club de mordus de l’informatique d’une prestigieuse université américaine le mouvement protéiforme et engagé que l’on connaît aujourd'hui, sur la Toile comme dans les Parlements. REMERCIEMENTS J’adresse toute ma gratitude aux hackers et hackeuses qui ont m’ont généreusement accordé leur temps et leur confiance, et ont été une grande source d’inspiration. La réalisation de ce mémoire a dépendu de leur participation, et leur est donc dédiée. -

SELECTED PAPERS Leadership and New Trends in Political

Autunn o 08 Emiliana De Blasio, Matthew Hibberd, Michele Sorice (eds) Leadership and New Trends in Political Communication SELECTED PAPERS Merja Almonkari, Ali Fuat Borovali, Mesut Hakki Caşin, Nigar Degirmenci, Alejandro De Marzo, Enrico Gandolfi, Gianluca Giansante, Pekka Isotalus, Darren G. Lilleker, Denisa Kasl Kollmannova, Ruben Arnoldo Gonzalez Macias, Karolina Koc-Michalska, Bianca Marina Mitu, Antonio Momoc, Zeynep Hale Oner, Mari K. Niemi, Norman Melchor Robles Peña, Lorenza Parisi, Giorgia Pavia, Francesco Pira, Ville Pitkanen, Kevin Rafter, Rossella Rega, Mariacristina Sciannamblo, Donatella Selva, Iryna Sivertsava, Agnese Vardanega CMCS Working Papers 2 CMCS Working Papers Leadership and new trends in political communication 3 Emiliana De Blasio – Matthew Hibberd – Michele Sorice (Eds) Leadership and New Trends in Political Communication Selected Papers Rome CMCS Working Papers © 2011 4 CMCS Working Papers Leadership and new trends in political communication 5 Published by Centre for Media and Communication Studies “Massimo Baldini” LUISS University Department of History and Political Sciences Viale Romania, 32 – 00197 Roma RM – Italy Copyright in editorial matters, CMCS © 2011 Copyright CMCS WP03/2011 – Leadership and new trends in political communication – The Authors © 2011 ISBN 978-88-6536-008-8 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission in writing of the publisher nor be issued to the public or circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published. In the interests of providing a free flow of debate, views expressed in this CMCS WP are not necessarily those of the editors or the LUISS University. -

Julian Assange - Wikileaks

Julian Assange - WikiLeaks Warrior for Truth by Valerie Guichaoua & Sophie Radermecker Virtual Words Translations - Natasha Cloutier With the collaboration of Franck Bachelin Julian Assange - WikiLeaks Warrior for Truth Published by Cogito Media Group. Copyright ©2011 Valerie Guichaoua & Sophie Radermecker The reproduction or transmission of any part of this publication in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording, or otherwise, or storage in a retrieval system, without prior consent of the publisher, is an infringe- ment of copyright law. In the case of photocopying or other reprographic production of the material, a license must be obtained from the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright) before proceeding. ISBN: 978-1-926893-55-6 Cover design: François Turgeon and Kayo Tomura Text design and composition: Benjamin Roland Cover photo: © Photography by Jillian Edelstein, CAMERA PRESS LONDON Authors photography: © Arber Kucana Cogito Media Group 279 Sherbrooke Street West Suite#305 Montréal, Quebec H2X 1Y2 CANADA Phone : + 1.514.273.0123 www.cogitomedias.com Printed and Bound in the United States of America Contents Acknowledgments 9 Foreword 13 Climax 19 Part I 25 1. Magnetic Island 27 2. Élise 33 Part II 43 3. Mendax 45 4. Hackers’ dialogue 52 5. Sophox 63 Part III 69 6. Élise and Xavier 71 7. Life Experience 79 Part IV 93 8. Maternal Influence 95 9. Inspiration and Reference 101 Part V 109 10. The Genesis of WikiLeaks 111 11. The Organization 116 12. The First Leaks 128 13. Julian as seen by Élise 139 Part VI 149 14. A Chain of Leaks 151 15. Project B 161 Part VII 177 16. -

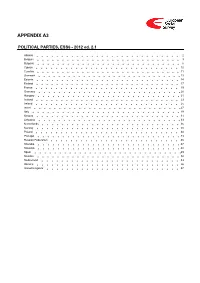

ESS6 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS6 - 2012 ed. 2.1 Albania 2 Belgium 3 Bulgaria 6 Cyprus 10 Czechia 11 Denmark 13 Estonia 14 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Israel 27 Italy 29 Kosovo 31 Lithuania 33 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 43 Russian Federation 45 Slovakia 47 Slovenia 48 Spain 49 Sweden 52 Switzerland 53 Ukraine 56 United Kingdom 57 Albania 1. Political parties Language used in data file: Albanian Year of last election: 2009 Official party names, English 1. Partia Socialiste e Shqipërisë (PS) - The Socialist Party of Albania - 40,85 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Partia Demokratike e Shqipërisë (PD) - The Democratic Party of Albania - 40,18 % election: 3. Lëvizja Socialiste për Integrim (LSI) - The Socialist Movement for Integration - 4,85 % 4. Partia Republikane e Shqipërisë (PR) - The Republican Party of Albania - 2,11 % 5. Partia Socialdemokrate e Shqipërisë (PSD) - The Social Democratic Party of Albania - 1,76 % 6. Partia Drejtësi, Integrim dhe Unitet (PDIU) - The Party for Justice, Integration and Unity - 0,95 % 7. Partia Bashkimi për të Drejtat e Njeriut (PBDNJ) - The Unity for Human Rights Party - 1,19 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Socialist Party of Albania (Albanian: Partia Socialiste e Shqipërisë), is a social- above democratic political party in Albania; it is the leading opposition party in Albania. It seated 66 MPs in the 2009 Albanian parliament (out of a total of 140). It achieved power in 1997 after a political crisis and governmental realignment. In the 2001 General Election it secured 73 seats in the Parliament, which enabled it to form the Government. -

Pirate Politics: Information Technologies and the Reconfiguration of Politics

Master Programe in Global Studies Master Thesis 30hp Pirate Politics: Information Technologies and the Reconfiguration of Politics December 2012 Author: Bruno Monico Chies Supervisor: Michael Schulz 1 Abstract This thesis sets out to address the question of how Information Technologies (ITs) become politically relevant, both by drawing on different theoretical approaches and by undertaking a qualitative study about the Swedish Pirate Party. The first source of puzzlement that composes our main research question is the phenomena of how ITs have been taking center stage in recent political disputes, such as controversial legislations in Sweden and abroad (ACTA, Data Retention Directive, etc.), and how a new public became engaged in the formation of a political party regarding these issues. This work will address different theoretical approaches, especially Actor- network Theory, in order to revisit how recent developments in information and communication technologies can be of political relevance. It will thus be proposed a political genealogy of ITs – from the moment they are developed to the moment they result in issues to be debated and resolved in the institutional political arena. It is the latter moment in particular, represented in the research of how the “pirates” make sense of ITs, that will be of significance in this thesis. The focus will be laid upon the role they see themselves playing in this larger process of politicization of ITs and how they are actively translating fundamental political values of democracy and freedom of speech. Keywords: Pirate Party; Information Technologies; Actor-Network Theory; Issues; Politics 2 Acknowledgements I am grateful to my interviewees, for dedicating their time to a foreign master student, to my supervisor Michael Schulz, for the patience of listening to a confused mind, to Anders Westerström, for helping me out with translations and finally to my beloved parents, my sambo Madelene Grip and friends for all the emotional support. -

AI for Better Health a Report on the Present Situation for Competitive Swedish AI in the Life Sciences Sector

AI for better health A report on the present situation for competitive Swedish AI in the life sciences sector Marcus Österberg and Lars Lindsköld – 1 – AI for better health A report on the present situation for competitive Swedish AI in the life sciences sector A lot is happening in artificial intelligence (AI). So far, not much of it has found its way into health and medical services, but this doesn’t mean there’s a lack of interest in future issues, only that it’s too early to evaluate a possible breakthrough for contemporary interest in AI. AI for better health should be seen from several different parallel time perspectives. • Yesterday’s AI for medical imaging and other expert systems, which has been in use for quite some time. • Today’s AI, which is held back by regulatory uncertainties and legislation that hinders progress and which appears to put protec- tion of an individual’s privacy above the individual’s health. • Tomorrow’s more general AI, which can behave like a human, understand and process human speech, and probably a lot more. Such an advance is probably not very far off if we can eliminate today’s challenges. Our clinical quality registers and personal ID numbers are often mentioned as being among our strengths, but if Sweden is not to lag behind it must get to grips with a number of things in addition to the rules and regulations. We need to work with digital sustainability issues, become even more digitally mature and not just focus on AI re- search, but rather make sure that AI gets implemented. -

The Evolving Agenda of European Pirate Parties

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Helsingin yliopiston digitaalinen arkisto International Journal of Communication 9(2015), 870–889 1932–8036/20150005 From File Sharing to Free Culture: The Evolving Agenda of European Pirate Parties JOHANNA JÄÄSAARI1 JOCKUM HILDÉN University of Helsinki, Finland In this article, we explore the challenge of shaping Pirate policies to match political context: how to safeguard the unity of digital rights, freedom of expression, privacy, and access while adapting to local political realities. The article examines the political programs of the Pirate Party in five countries to present a representative image of contemporary Pirate politics. The analysis shows that the Pirate Party platform has extended to more broad notions of culture, participation, and self-expression. While the trinity of digital rights persists, a process of reframing and reconfiguring Pirate politics is detectable where the political arm of the movement has gradually drifted apart from core activists holding on to the idea of preserving digital rights as a single issue. Keywords: piracy, Pirate Party, privacy, copyright, digital rights Introduction The Pirate Party was first launched in Sweden in 2006 following a protest against the raid of the file-sharing site The Pirate Bay by the Swedish police (Ilshammar, 2010). What began as a protest against antipiracy measures in one single country has since transformed into a transnational network of party organizations campaigning for cyberlibertarian reforms. The Swedish Pirate Party’s initial success in raising the file-sharing debate within the formal political decision-making system inspired like-minded individuals to establish national Pirate parties in several other countries, including Germany, France, and Austria in 2006, the same year that the Swedish party was founded.