Dave Chappell 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Key Data Report Hayfield Pyramid Spring 2019 Release

Learning Provision Organisation: Key Data Report Hayfield Pyramid Spring 2019 Release Analysis of school and childcare provision within the Hayfield pyramid. 1 Final Vs. 02/2019 Contents 1. Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................. 4 1a. Demographic ................................................................................................................................. 4 1b. Schools .......................................................................................................................................... 4 1c. Childcare and Early Years .............................................................................................................. 5 1d. SEND ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….5 1e. Key Points ...................................................................................................................................... 5 2. The Pyramid in Context ....................................................................................................................... 6 2a. Overview ....................................................................................................................................... 6 2b. Demographics and Population ...................................................................................................... 6 2c. Pyramid Profile ............................................................................................................................. -

Allocations Document

East Riding Local Plan 2012 - 2029 Allocations Document PPOCOC--L Adopted July 2016 “Making It Happen” PPOC-EOOC-E Contents Foreword i 1 Introduction 2 2 Locating new development 7 Site Allocations 11 3 Aldbrough 12 4 Anlaby Willerby Kirk Ella 16 5 Beeford 26 6 Beverley 30 7 Bilton 44 8 Brandesburton 45 9 Bridlington 48 10 Bubwith 60 11 Cherry Burton 63 12 Cottingham 65 13 Driffield 77 14 Dunswell 89 15 Easington 92 16 Eastrington 93 17 Elloughton-cum-Brough 95 18 Flamborough 100 19 Gilberdyke/ Newport 103 20 Goole 105 21 Goole, Capitol Park Key Employment Site 116 22 Hedon 119 23 Hedon Haven Key Employment Site 120 24 Hessle 126 25 Hessle, Humber Bridgehead Key Employment Site 133 26 Holme on Spalding Moor 135 27 Hornsea 138 East Riding Local Plan Allocations Document - Adopted July 2016 Contents 28 Howden 146 29 Hutton Cranswick 151 30 Keyingham 155 31 Kilham 157 32 Leconfield 161 33 Leven 163 34 Market Weighton 166 35 Melbourne 172 36 Melton Key Employment Site 174 37 Middleton on the Wolds 178 38 Nafferton 181 39 North Cave 184 40 North Ferriby 186 41 Patrington 190 42 Pocklington 193 43 Preston 202 44 Rawcliffe 205 45 Roos 206 46 Skirlaugh 208 47 Snaith 210 48 South Cave 213 49 Stamford Bridge 216 50 Swanland 219 51 Thorngumbald 223 52 Tickton 224 53 Walkington 225 54 Wawne 228 55 Wetwang 230 56 Wilberfoss 233 East Riding Local Plan Allocations Document - Adopted July 2016 Contents 57 Withernsea 236 58 Woodmansey 240 Appendices 242 Appendix A: Planning Policies to be replaced 242 Appendix B: Existing residential commitments and Local Plan requirement by settlement 243 Glossary of Terms 247 East Riding Local Plan Allocations Document - Adopted July 2016 Contents East Riding Local Plan Allocations Document - Adopted July 2016 Foreword It is the role of the planning system to help make development happen and respond to both the challenges and opportunities within an area. -

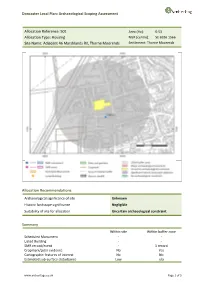

Doncaster Local Plan: Archaeological Scoping Assessment

Doncaster Local Plan: Archaeological Scoping Assessment Allocation Reference: 501 Area (Ha): 0.53 Allocation Type: Housing NGR (centre): SE 6936 1566 Site Name: Adjacent 46 Marshlands Rd, Thorne Moorends Settlement: Thorne Moorends Allocation Recommendations Archaeological significance of site Unknown Historic landscape significance Negligible Suitability of site for allocation Uncertain archaeological constraint Summary Within site Within buffer zone Scheduled Monument - - Listed Building - - SMR record/event - 1 record Cropmark/Lidar evidence No Yes Cartographic features of interest No No Estimated sub-surface disturbance Low n/a www.archeritage.co.uk Page 1 of 3 Doncaster Local Plan: Archaeological Scoping Assessment Allocation Reference: 501 Area (Ha): 0.53 Allocation Type: Housing NGR (centre): SE 6936 1566 Site Name: Adjacent 46 Marshlands Rd, Thorne Moorends Settlement: Thorne Moorends Site assessment Known assets/character: The SMR does not record any features within the site. One findspot is recorded within the buffer zone, a Bronze Age flint arrowhead. No listed buildings or Scheduled Monuments are recorded within the site or buffer zone. The Magnesian Limestone in South and West Yorkshire Aerial Photographic Mapping Project records levelled ridge and furrow remains within the buffer zone. The Historic Environment Characterisation records the present character of the site as modern commercial core- suburban, probably associated with the construction of Moorends mining village in the first half of the 20th century. There is no legibility of the former parliamentary enclosure in this area. In the western part of the buffer, the landscape character comprises land enclosed from commons and drained in 1825, with changes to the layout between 1851 and 1891 in association with the construction of a new warping system. -

Secondary Planning Area Report Hayfield and Rossington

Learning Provision Organisation: Secondary Planning Area Report Hayfield and Rossington 2020 Release Analysis of school and childcare provision within the Hayfield and Rossington pyramids. 1 Contents 1. Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................. 4 1a. Demographic ................................................................................................................................. 4 1b. Schools .......................................................................................................................................... 4 1c. Childcare and Early Years .............................................................................................................. 4 1d. SEND .............................................................................................................................................. 5 1e. Key Points ...................................................................................................................................... 5 2. The Locality in Context ........................................................................................................................ 6 2a. Overview ....................................................................................................................................... 6 2b. Demographics and Population ...................................................................................................... 6 2c. Locality Profile .............................................................................................................................. -

Town & Country Planning Act 1990

Town Planning & Development Consultants TOWN & COUNTRY PLANNING ACT 1990 Joint Applications by Peel Environmental Ltd & Tetron Finningley LLP Proposal: Finningley Quarry Restoration Scheme Site at: Finningley Quarry, Old Bawtry Road, Austerfield, Doncaster, DN10 6HL STATEMENT IN SUPPORT OF SECTION 73 PLANNING APPLICATIONS TO REMOVE & VARY CONDITIONS ATTACHED TO PREVIOUS PLANNING PERMISSIONS Prepared by Paul Semple BA(Hons) MRTPI November 2012 © Copyright JWPC Ltd: All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be copied, reproduced or transmitted in any format, or the format of the report be used, without prior permission from JWPC Ltd. 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 This Planning Support Statement has been prepared to accompany three applications to vary or remove conditions attached to planning permissions related to restoration of previous sand and gravel workings at Finningley Quarry, Old Bawtry Road, Austerfield, Doncaster. They have been submitted by Peel Environmental Ltd, owners of the quarry and Tetron Finningley LLP, the intended operators. 1.2 The applications are made pursuant to Section 73 of the Town & Country Planning Act 1990 (as amended) and seek to vary or remove conditions attached to planning permission 10/03132/WCC, 10/03137/WCC and 10/03140/WCC, as a result of a change to the vehicular access to the quarry, the subsequent phasing of restoration work and the use of different materials for infilling. 1.3 The Statement is in six sections and comprises: 1.0 Introduction 2.0 Site & Surrounding Area 3.0 Relevant Planning History 4.0 Planning Applications 5.0 Planning Policies 6.0 Planning Considerations 1.4 The planning applications are accompanied by reports by AAe on: a Restoration Dust Management Strategy a Noise Monitoring Scheme a Hydrogeological Risk Assessment 2.0 SITE & SURROUNDING AREA 2.1 Finningley Quarry has a long history of mineral extraction as a sand and gravel quarry since the 1950s. -

Asking Price Of: £300,000

F 46 Old Road Holme On Spalding Moor Chartered Surveyors YO43 4AE Beautifully appointed family Outstanding landscaped home gardens Asking Price Of: Double garage Extended accommodation £300,000 Multiple car parking on the drive within easy access of M62 01377 253456 www.ullyotts.co.uk [email protected] 46 Old Road HOLME ON SPALDING MOOR Holme-on-Spalding-Moor (also known as Holme-upon- Holme On Spalding Moor Spalding-Moor) is a large village and civil parish in the YO43 4AE East Riding of Yorkshire. It is situated approximately 8 miles north-east of Howden and 5 miles south-west of Market Weighton. It lies on the A163 road where it joins the A614 road. In terms of major cities, the village is closest to York which is just under 20 miles away, while Hull is 23 miles away. ACCOMMODATION HALLWAY With staircase off leading to the first floor. Fitted oak flooring. Victorian style radiator and built-in cupboard housing a gas fired boiler. CLOAKROOM/WC With contemporary white suite having push button WC and fitted vanity unit with mixer tap basin. Part- Located within a prime residential area within tiled walls and ladder style radiator. Fitted oak Holme on Spalding Moor and having been flooring. attractively extended, this is simply an outstanding detached residence offering beautifully appointed LIVING ROOM family orientated accommodation with plentiful off- 23' 3" x 12' 11" (7.11m x 3.96m) street parking and a delightful garden ideal for Been slightly 'L' shaped with double glazed window entertaining. to the front aspect. Fitted oak flooring and feature reconstituted stone fireplace with inset electric fire. -

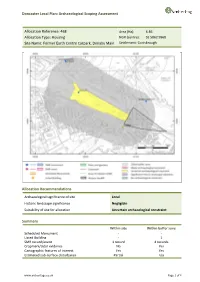

Doncaster Local Plan: Archaeological Scoping Assessment

Doncaster Local Plan: Archaeological Scoping Assessment Allocation Reference: 468 Area (Ha): 6.86 Allocation Type: Housing NGR (centre): SE 5062 9968 Site Name: Former Earth Centre Carpark, Denaby Main Settlement: Conisbrough Allocation Recommendations Archaeological significance of site Local Historic landscape significance Negligible Suitability of site for allocation Uncertain archaeological constraint Summary Within site Within buffer zone Scheduled Monument - - Listed Building - 1 SMR record/event 1 record 4 records Cropmark/Lidar evidence No Yes Cartographic features of interest Yes Yes Estimated sub-surface disturbance Partial n/a www.archeritage.co.uk Page 1 of 4 Doncaster Local Plan: Archaeological Scoping Assessment Allocation Reference: 468 Area (Ha): 6.86 Allocation Type: Housing NGR (centre): SE 5062 9968 Site Name: Former Earth Centre Carpark, Denaby Main Settlement: Conisbrough Site assessment Known assets/character: The SMR records one monument within the site, the site of the 19th-century Providence Glassworks, located at the western side of the site. Four findspots are located within the buffer zone, all surface finds of flint artefacts, mainly dating to the Mesolithic period and recovered from near Cadeby Cliff to the northeast of the site and the Ings to the northwest. No Scheduled Monuments or listed buildings are recorded within the site. One grade II listed milepost is located within the buffer zone. The Magnesian Limestone in South and West Yorkshire Aerial Photographic Mapping Project did not record any features within the site. Within the buffer, 20th-century air raid shelters and post-medieval terraced ground in the southern part of the buffer. Historic Environment Characterisation records the landscape character within the site as a mixture of Modern Regenerated Scrubland and Suburban Commercial Core. -

Economic Recovery Update

COVID-19 RESILIENCE, RENEWAL AND RECOVERY COMMITTEE: ECONOMIC RECOVERY UPDATE Status: Not yet started Active Active but paused Completed Theme Timeline Business Specific January 2021 Update Goal actions Between Job creation Support the Measures aimed at supporting a green recovery: in response to the now and programme hardest-hit economic impacts of COVID-19, the Council continues to offer creative March sectors improvements to the housing stock, reinforcing Nottinghamshire as a 2021 great place to live, work, visit and relax. Recent approvals will help some of Nottinghamshire’s more vulnerable fuel-poor households living in poorly insulated homes. - The £4.3M Warm Homes Hub two-year partnership with EoN and local authority partners means eligible homeowners and tenants (+ 500 houses) will be able to improve the warmth and comfort of their home and benefit from free services such as grid connection and first- time central heating. While halted initially due to COVID-19, the programme is now being rolled out across the County. To date, there has been eight new gas heating system installations with a further 25 households going through the process. In addition, E.ON are planning delivery to a site of 72 Flats - designs are being drawn up for 72 individual gas central heating systems, alongside a complete district heating network. A further 837 households have been supported against the 1,000 households target. An extra £1M (serving an additional 100+ homes at least) was secured for additional measures. - A bid is currently under consideration by Government for an additional £2.3M to facilitate additional energy efficiency measures to more communities under the Green Homes Grant Local Authority Delivery Phase 1B. -

Doncaster Metropolitan Borough Council

DONCASTER METROPOLITAN BOROUGH COUNCIL PLANNING COMMITTEE - 13th March 2012 Application 01 Application 11/03356/FULM Application 19th March 2012 Number: Expiry Date: Application Planning FULL Major Type: Proposal Erection of biomass renewable energy facility, associated landscaping Description: and vehicular access At: Land Off A614 Lindholme Doncaster For: Vulcan Renewables Third Party Reps: 0 Parish: Hatfield Parish Council Ward: Thorne Author of Report Mark Sewell MAIN RECOMMENDATION: GRANT 1.0 Reason for Report 1.1 The application is being presented to the Planning Committee as it represents a departure from the adopted development plan. 2.0 Proposal and Background 2.1 The proposed development involves the construction of a locally sourced biomass fuelled, renewable energy facility. The proposed facility will convert approximately 35000 tonnes of locally sourced biomass into biogas per annum, which will be transferred into the gas network for local and national use. 2.2 The proposal comprises of plant and structures for the storage of feedstock material and bio-fertiliser, a biogas digester, biogas holder, leachate storage tank, gas to grid processing unit, attenuation pond, earth bunding and ancillary structures and buildings. The facility will consist primarily of three tanks (9m height x 23m diameter; 13m height x 28m diameter; 13m height x 34m diameter), together with a silage clamp of earth bund design covering 6000 sq. metres. 2.3 The application site itself is located on the western side of the A614 road, opposite the junction with Vulcan Way, Lindholme village. The site is currently agricultural land, with an area of approximately 5 hectares, and surrounding by similar agricultural land to the north, south and west. -

Newsletter Then the 'Read More' Tags Will Take You to the Appropriate Pages on the Website Where You Will Find More Details About the Particular Topic Or Event

Working together: what we do best Volume 2, Issue 10, June 2016 Bring the past to life with the 'Discover Nottingham's History' app. More than just history, uncover the highlights and rarities of Nottingham Central Library's extensive Local Studies collection. Launching on Thursday 30 June, download this free app to your apple or android device and get started exploring the unusual and captivating history of Nottingham - its people, industry and way of life - revealed through over 600 years of materials …Read more. Nottingham's Historic Green Spaces, Programme of Events Nottingham’s Historic Green Spaces Project is arranging a series of events that will happen over the summer. Some are for adults and some for children, and some suitable for all ages. We hope that everyone will find something to their taste and will join us at least once. Please put these dates in your diary. Breathing Spaces Community Play • 16 July Queen's Walk Recreation Ground (noon) • 17 July The Forest (noon) and Victoria Park (4:30pm) • 24 July The Arboretum (noon and 4:00pm) Victorian Children's Games • 16 July Queen's Walk Recreation Ground • 24 July The Arboretum • 16 August Local Studies Library (Nottingham Central Library) Exhibition Local Studies Library (Nottingham Central Library) throughout August Poetry Competition Read more. Are you aware of the Nottingham Heritage Strategy? As you might or might not know stakeholders throughout Nottingham launched a Heritage Strategy for the City last year. The heritage strategy documents can be viewed at: www.nottinghamcity.gov.uk/article/30396/Nottingham-Heritage-Strategy As part of the strategy there is a plan to establish a heritage partnership/forum for the City that will be open to all those groups and individuals who have a stake in heritage within Nottingham… Read more. -

East Riding Historic Designed Landscapes

YORKSHIRE GARDENS TRUST East Riding Historic Designed Landscapes NESWICK HALL PARKLAND Report by David and Susan Neave May 2013 1. CORE DATA 1.1 Name of site: Neswick Hall Parkland, Neswick 1.2 Grid reference: SE 975530 1.3 Administrative area: Bainton Civil Parish, East Riding Unitary Authority 1.4 Current site designation: Not registered 2. SUMMARY OF HISTORIC INTEREST The former parkland of Neswick Hall with its boundary plantations provides a good example of the typical layout of a modest mid-18th century designed landscape. Of particular interest is the restored walled kitchen garden. 3. HISTORIC DEVELOPMENT OF THE SITE 3.1 Estate owners The Neswick estate was held by the Salvin family of Kilham and Nafferton for two hundred years until it was sold to Thomas Anlaby of Etton in 1613. It descended in the Anlaby family until the death c. 1710 of Matthew Anlaby of Lebberston (North Riding) when the estate was divided between his five daughters. In 1714 Thomas Eyres, a Hull surgeon, husband of one of the heiresses, purchased the other four shares and became sole owner of Neswick. (Neave & Needham, ‘Neswick Hall’, 12) Esther, one of Eyres’ two daughters and eventual heiresses, married Robert Grimston, attorney, of Bridlington. Esther Grimston inherited half the Neswick estate by 1743, then three years later Robert Grimston purchased the other half. On the death of Robert’s grandson John Grimston in 1846 the estate passed in turn to the younger sons of his elder sister Lucy, wife of Sir Robert Wilmot, Bt. When the fourth son John Wilmot (1807-79) succeeded to the estate in 1860 he took the name of Grimston. -

“Making It Happen” PPOC-EOOC-E

East Riding Local Plan 2012 - 2029 Allocations Document PPOCOC--L Adopted July 2016 “Making It Happen” PPOC-EOOC-E Contents Foreword i 1 Introduction 2 2 Locating new development 7 Site Allocations 11 3 Aldbrough 12 4 Anlaby Willerby Kirk Ella 16 5 Beeford 26 6 Beverley 30 7 Bilton 44 8 Brandesburton 45 9 Bridlington 48 10 Bubwith 60 11 Cherry Burton 63 12 Cottingham 65 13 Driffield 77 14 Dunswell 89 15 Easington 92 16 Eastrington 93 17 Elloughton-cum-Brough 95 18 Flamborough 100 19 Gilberdyke/ Newport 103 20 Goole 105 21 Goole, Capitol Park Key Employment Site 116 22 Hedon 119 23 Hedon Haven Key Employment Site 120 24 Hessle 126 25 Hessle, Humber Bridgehead Key Employment Site 133 26 Holme on Spalding Moor 135 27 Hornsea 138 East Riding Local Plan Allocations Document - Adopted July 2016 Contents 28 Howden 146 29 Hutton Cranswick 151 30 Keyingham 155 31 Kilham 157 32 Leconfield 161 33 Leven 163 34 Market Weighton 166 35 Melbourne 172 36 Melton Key Employment Site 174 37 Middleton on the Wolds 178 38 Nafferton 181 39 North Cave 184 40 North Ferriby 186 41 Patrington 190 42 Pocklington 193 43 Preston 202 44 Rawcliffe 205 45 Roos 206 46 Skirlaugh 208 47 Snaith 210 48 South Cave 213 49 Stamford Bridge 216 50 Swanland 219 51 Thorngumbald 223 52 Tickton 224 53 Walkington 225 54 Wawne 228 55 Wetwang 230 56 Wilberfoss 233 East Riding Local Plan Allocations Document - Adopted July 2016 Contents 57 Withernsea 236 58 Woodmansey 240 Appendices 242 Appendix A: Planning Policies to be replaced 242 Appendix B: Existing residential commitments and Local Plan requirement by settlement 243 Glossary of Terms 247 East Riding Local Plan Allocations Document - Adopted July 2016 Contents East Riding Local Plan Allocations Document - Adopted July 2016 Foreword It is the role of the planning system to help make development happen and respond to both the challenges and opportunities within an area.