Past Problems and Current Issues in Canadian Telecommunication Policy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Four Courts of Sir Lyman Duff

THE FOUR COURTS OF SIR LYMAN DUFF RICHARD GOSSE* Vancouver I. Introduction. Sir Lyman Poore Duff is the dominating figure in the Supreme Court of Canada's first hundred years. He sat on the court for more than one-third of those years, in the middle period, from 1906 to 1944, participating in nearly 2,000 judgments-and throughout that tenure he was commonly regarded as the court's most able judge. Appointed at forty-one, Duff has been the youngest person ever to have been elevated to the court. Twice his appointment was extended by special Acts of Parliament beyond the mandatory retirement age of seventy-five, a recogni- tion never accorded to any other Canadian judge. From 1933, he sat as Chief Justice, having twice previously-in 1918 and 1924 - almost succeeded to that post, although on those occasions he was not the senior judge. During World War 1, when Borden considered resigning over the conscription issue and recommending to the Governor General that an impartial national figure be called upon to form a government, the person foremost in his mind was Duff, although Sir Lyman had never been elected to public office. After Borden had found that he had the support to continue himself, Duff was invited to join the Cabinet but declined. Mackenzie King con- sidered recommending Duff for appointment as the first Canadian Governor General. Duff undertook several inquiries of national interest for the federal government, of particular significance being the 1931-32 Royal Commission on Transportation, of which he was chairman, and the 1942 investigation into the sending of Canadian troops to Hong Kong, in which he was the sole commissioner . -

Government Series RG 8-20 Despatches of the Department of the Provincial Secretary

List of: Government Series RG 8-20 Despatches of the Department of the Provincial Secretary Reference File Item Title and Physical Description Date Ordering Information Code Code RG 8-20 100.001 Imperial Cancer Research Fund 1910-1911 To view, order RG 8-20, in 1 file of textual records container B224124 RG 8-20 100.002 Judge D.W. McIntyre, Judge of County Court at Whitby 1910 To view, order RG 8-20, in 1 file of textual records container B224124 RG 8-20 100.003 Indian and Ordinance Lands 1910-1943 To view, order RG 8-20, in 1 file of textual records container B224124 RG 8-20 100.004 Erasures from the Medical and Dental Register 1909-1933 To view, order RG 8-20, in 1 file of textual records container B224124 RG 8-20 100.005 Privy Council Minutes for January 17th 1910 To view, order RG 8-20, in 1 file of textual records container B224124 RG 8-20 100.006 Complaints of [Name withheld under the Freedom of 1910 To view, order RG 8-20, in Information and Protection of Privacy Act] of Lynden, container B224124 Ontario, against H.E.P.C. 1 file of textual records RG 8-20 100.007 Request by Secretary of State for copy of Ontario 1910-1931 To view, order RG 8-20, in sessional papers container B224124 1 file of textual records RG 8-20 100.008 Appointment of A.J. Comber of Port Arthur, as the 1910 To view, order RG 8-20, in Consular Agent of the U.S.A. -

Uot History Freidland.Pdf

Notes for The University of Toronto A History Martin L. Friedland UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO PRESS Toronto Buffalo London © University of Toronto Press Incorporated 2002 Toronto Buffalo London Printed in Canada ISBN 0-8020-8526-1 National Library of Canada Cataloguing in Publication Data Friedland, M.L. (Martin Lawrence), 1932– Notes for The University of Toronto : a history ISBN 0-8020-8526-1 1. University of Toronto – History – Bibliography. I. Title. LE3.T52F75 2002 Suppl. 378.7139’541 C2002-900419-5 University of Toronto Press acknowledges the financial assistance to its publishing program of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council. This book has been published with the help of a grant from the Humanities and Social Sciences Federation of Canada, using funds provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. University of Toronto Press acknowledges the finacial support for its publishing activities of the Government of Canada, through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program (BPIDP). Contents CHAPTER 1 – 1826 – A CHARTER FOR KING’S COLLEGE ..... ............................................. 7 CHAPTER 2 – 1842 – LAYING THE CORNERSTONE ..... ..................................................... 13 CHAPTER 3 – 1849 – THE CREATION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO AND TRINITY COLLEGE ............................................................................................... 19 CHAPTER 4 – 1850 – STARTING OVER ..... .......................................................................... -

Introduction

backhouse 02text (xi-322) 4/22/04 4:06 PM Page 3 INTRODUCTION Y about to meet Mrs. Elizabeth Bethune Campbell, a woman of formidable intellect, wit, and sarcasm, with the determination of steel. Her book, Where Angels Fear to Tread, written in and self- published in from her home in the rectory of St. John’s Episcopalian Church in Jamaica Plain, Boston, raised considerable controversy when it first appeared. Mrs. Campbell’s fascinating entan- glement with the law spanned fourteen years. It began in , when she first came across an unsigned copy of her mother’s will while sort- ing through musty family trunks. The saga peaked in , when Mrs. Campbell appeared on her own behalf to argue her case in front of the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in London. The legal battle finally ended in , when the Ontario Court of Appeal issued its last decision on the matter of costs relating to the complex web of litiga- tion spawned by Mrs. Campbell’s inheritance. The story that Mrs. Campbell tells is extraordinary, and not only because she appears to have been the first woman to argue in front of the Law Lords at the Privy Council. Mrs. Campbell’s description of the barriers she surmounted before emerging victorious in England unveils the intricate, multilayered world of overlapping intrigue and influence that constituted the early-twentieth-century Ontario legal system. From her unique vantage point as both an insider and an out- sider, she comments on the actions of lawyers and judges with acuity and perspicacity. Others might have thought as she did. -

“A Matter of Deep Personal Conscience”: the Canadian Death-Penalty Debate, 1957-1976

“A Matter of Deep Personal Conscience”: The Canadian Death-Penalty Debate, 1957-1976 by Joel Kropf, B.A. (Hons.) A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario July 31,2007 © 2007 Joel Kropf Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Library and Bibliotheque et Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-33745-5 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-33745-5 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce,Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve,sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet,distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform,et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

OFSAA Championship 2018 - 2/27/2018 to 2/28/2018 Results

Windsor Aquatic Club HY-TEK's MEET MANAGER 7.0 - 6:34 PM 2/28/2018 Page 1 OFSAA Championship 2018 - 2/27/2018 to 2/28/2018 Results Event 1 Girls 13-19 200 SC Meter Freestyle Open OFSAA Record: 2:00.40 R 2013 Victoria Chan HAVC 2:18.40 OFSA OFSAA Name Age Team Prelim Time Finals Time A - Final 1 Mage, Lauren 15 D8 St Benedict Css-Cwossa 2:07.23 2:03.32 OFSA 29.21 1:00.56 1:32.00 2:03.32 2 Meklensek, Tori 14 Waterloo Ci-Cwossa 2:10.80 2:07.73 OFSA 29.80 1:02.21 1:35.01 2:07.73 3 Richard, Sophie 14 Waterloo Ci-Cwossa 2:10.44 2:08.53 OFSA 30.24 1:02.90 1:36.02 2:08.53 4 Mehare, Amy 13 Glendale High School-wo 2:12.23 2:09.79 OFSA 30.51 1:03.62 1:37.00 2:09.79 5 Storm, Jordan 15 Glebe Collegiate Inst Ncssaa 2:10.36 2:09.93 OFSA 30.83 1:03.49 1:37.13 2:09.93 6 Reibel, Jessica 15 Bluevale Collegiate-cwossa 2:10.67 2:10.43 OFSA 30.70 1:03.82 1:37.85 2:10.43 7 Studebaker, Gabby 16 Niagara Christian Coll-sossa 2:11.66 2:11.23 OFSA 30.47 1:03.24 1:37.94 2:11.23 8 Fenton, Chilyn 16 Innisdale -gbssa 2:13.55 2:14.95 OFSA 31.02 1:04.94 1:40.12 2:14.95 B - Final 9 Lloyd, Andie 13 Sir Winston Churchill-sossa 2:13.93 2:13.29 OFSA 30.73 1:04.43 1:39.16 2:13.29 10 Singh, Angelique 13 Mayfield Ss-Ropssaa 2:14.53 2:13.83 OFSA 31.12 1:05.07 1:39.96 2:13.83 11 Vi, Kyanna 15 D8 St Benedict Css-Cwossa 2:16.50 2:14.39 OFSA 30.75 1:04.49 1:39.31 2:14.39 12 Ashton, Clare 15 Southwood Ss-Cwossa 2:16.35 2:15.05 OFSA 31.65 1:06.14 1:41.09 2:15.05 13 Milutinovic, Jovana 16 Lorne Park Ss-Ropssaa 2:16.40 2:15.84 OFSA 31.16 1:05.54 1:40.45 2:15.84 14 Schlotzhauer, Hanna 13 -

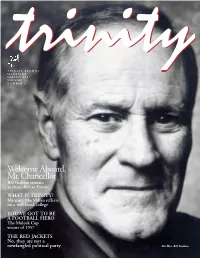

Welcome Aboard, Mr.Chancellor

17915 Trinity 4/25/07 2:09 PM Page 1 TRINITY ALUMNI MAGAZINE SPRING 2007 VOLUME 44 NUMBER 2 Welcome Aboard, Mr.Chancellor Bill Graham returns, as chancellor, to Trinity WHAT IS TRINITY? Margaret MacMillan reflects on a well-loved college YOU’VE GOT TO BE A FOOTBALL HERO The Mulock Cup victors of 1957 THE RED JACKETS No, they are not a newfangled political party The Hon. Bill Graham 17915 Trinity 4/25/07 2:09 PM Page 2 FromtheProvost The Last Word In her final column as Provost, Margaret MacMillan takes her leave with a fervent ‘Thank you, all’ hen I became Provost of this college five years not mean slavishly keeping every tradition, but picking out what was ago, I discovered all sorts of unexpected duties, important in what we inherited and discarding what was not. Estab- such as the long flower bed along Hoskin lished ways of doing things should never become a straitjacket. In W Avenue. When Bill Chisholm, then the build- my view, Trinity’s key traditions are its openness to difference, ing manager, told me on a cold January day that the Provost whether in ideas or people, its generous admiration for achievement always chose the plants, I did the only sensible thing and called in all fields, its tolerance, and its respect for the rule of law. my mother. She has looked after it ever since, with the results that I have made some changes while I have been here. Perhaps the so many of you have admired every summer. I also learned that I ones I feel proudest of are creating a single post of Dean of Students had to write this letter three times a year for the magazine. -

Tam CANADA YMAR BOOK 1905. July 24. George Hadley Vicars Bulyea of Regina, to Be Lieutenant from 1St September Lieutenant Governor of the Province of Governors

xl tAM CANADA YMAR BOOK 1905. July 24. George Hadley Vicars Bulyea of Regina, to be Lieutenant from 1st September Lieutenant Governor of the province of Governors. Alberta. July 24. Amed^e Emmanuel Forget, of Regina, to be from 1st September Lieutenant Governor of the province of Sas katchewan. May 22. Charles Smith Hyman, a member of the king's Ministerial Privy Council for Canada, to be Minister of Public Works in changes. the room and stead of Hon. James Sutherland, deceased. Oct. 16. Allen Bristol Aylesworth, a member of the king's Privy Council for Canada, to be Postmaster General of Canada in the room and stead of the Hon. Sir William Mulock resigned. Jan. 7. James Henry Ashdown of Winnipeg, to be a member Commis of the Commission to inquire into and report upon questions sioners. affecting the transportation of Canadian products to the markets of the world through and by Canadian ports, etc., in the room and stead of John Bertram, Esq., deceased. Jan. 7. James P. Mabee of Toronto, bariister-at-law, and Louis Coste of Ottawa, civil engineer, to be members of the International Commission to investigate and report upon the conditions and uses of the waters adjacent to the boundary line between the United States and Canada. William Frederick King, chief astronomer, was appointed a member of the Com mission by Order in Council of December 3, 1904. Feb. 6. Albert Clement Killam of Ottawa, to be the Chief Commissioner of the Board of Railway Commissioners in the room and stead of Hon. Andrew George Blair, resigned. -

Labor Legislation in Canada William Renwick Riddell

University of Minnesota Law School Scholarship Repository Minnesota Law Review 1921 Labor Legislation in Canada William Renwick Riddell Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/mlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Riddell, William Renwick, "Labor Legislation in Canada" (1921). Minnesota Law Review. 2510. https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/mlr/2510 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Minnesota Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Minnesota Law Review collection by an authorized administrator of the Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MINNESOTA LAW REVIEW Vol. V JANUARY, 1921 No. 2 LABOR LEGISLATION IN CANADA By WILLIAm RENWICK RIDDELL* THE economical problems of Canada are not different from those of the United States except in unimportant minutiae; and the answers attempted in the one country may not be without interest in the other. In these papers some account will be given of the legislation in Canada in the matter of labor, strikes, and the like.' The earliest legislation of the Dominion followed somewhat closely the existing legislation in England. The Imperial Parlia- ment in 1896 passed an act2 of which the principle as stated by its proposer was "to endeavor to establish a system of settling 3 disputes between employers and employed, by conciliation. It *Justice of the Supreme Court of Ontario, Toronto, Canada. 1 There is no pretence at originality in these papers; nearly all of the materials for them will be found in an article by Mr. F. A. -

Illuminating the Past Brightening the Future

1903 –2003 By Edward E. Seymour • Local Union 353 • International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers • AN ILLUSTRATED HISTORY • International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers • Local Union 353 • 1903 –2003 By Edward E. Seymour 1903 2003 ILLUMINATING THE PAST YEARS of Electrifying Progress BRIGHTENING THE FUTURE BRIGHTENING THE FUTURE AN ILLUSTRATED HISTORY AN ILLUSTRATED HISTORY • International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers Local Union 353 1903 –2003 ILLUMINATING THE PAST By Edward E. Seymour 1903 2003 ILLUMINATING THE PAST YEARS of Electrifying Progress BRIGHTENING THE FUTURE AN ILLUSTRATED HISTORY International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers Local Union 353 1903 –2003 By Edward E. Seymour 1903 2003 YEARS of Electrifying Progress Edward E. Seymour Edward E. Seymour is the owner of Solidarity Consulting, a labour relations consulting firm for unions. He is also a partner with Michael Lyons and Sherril Murray in Resolutions Unlimited (2000), a firm that concentrates on resolving harassment and discrimina- tion issues in the work place. Ed serves as a nominee on arbitration boards for several unions including the Ontario Public Service Employees Union, the Canadian Union of Public Employees and the Communications Energy and Paper Workers Union. Born in Port aux Basques, Newfoundland and raised in Sydney, Nova Scotia, Ed moved to Ontario in 1958. His trade union experience dates from 1962 when he became a member of Lodge 1246 of the International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers. He received his Bachelor of Arts in Political Science from the University of Waterloo in 1974 after attending classes during the day and working at night. Ed was the Canadian Education and Publicity Director for the Textile Workers Union of America (now part of U.N.I.T.E.) from 1970 to 1977. -

Introducing Darwinism to Toronto's Post-1887 Reconstituted

Introducing Darwinism to Toronto’s Post-1887 Reconstituted Medical School JOHN P. M. COURT “The boys sang their best songs and cheered with renewed vigour.” —The Mail (Toronto), 1890 Abstract. Charles Darwin’s scientific paradigm was largely welcomed in Cana- dian academic biology and medicine, while reaction among other faculty and laypeople ranged from interest to outrage. In 1874, Ramsay Wright, a Darwin- ian-era biologist from Edinburgh, was appointed to the University of Toronto’s Chair of Natural History. Over his 38-year career Wright integrated the evolu- tionary perspective into medical and biology teaching without accentuating its controversial source. He also applied the emerging German experimental research model and laboratory technology. This study identifies five categories of scientific and personal influences upon Wright through archival research on biographical sources and his writings. Keywords. natural history, biology, Darwinian evolution, medical education Résumé. Les théories de Charles Darwin ont été largement acceptées au Canada en médecine et en biologie, alors que les réactions au sein d’autres dis- ciplines et parmi la population allaient de l’intérêt à l’indignation. En 1874, Ramsay Wright, un biologiste d’Édinbourg, devint titulaire de la chaire d’his- toire naturelle à l’Université de Toronto. Pendant 38 ans de carrière, Wright a intégré la perspective évolutionniste dans son enseignement en médecine et en biologie, mais sans faire part de sa source controversée. Il a aussi utilisé la tech- nologie de laboratoire et le modèle de recherche expérimentale allemands, alors en émergence. Cette étude identifie cinq catégories d’influences personnelles et scientifiques perceptibles chez Wright, partant de ses écrits et de documents d’archives à caractère biographique. -

ONTARIO (Canada) Pagina 1 Di 3 ONTARIO Denominato Dal Lago Ontario, Che Prese Il Suo Nome Da Un Linguaggio Nativo Americano

ONTARIO (Canada) ONTARIO Denominato dal Lago Ontario, che prese il suo nome da un linguaggio nativo americano, derivante da onitariio=lago bellissimo, oppure kanadario=bellissimo, oppure ancora dall’urone ontare=lago. A FRANCIA 1604-1763 A GB 1763-1867 - Parte del Quebec 1763-1791 - Come Upper Canada=Canada Superiore=Alto Canada 24/08/1791-23/07/1840 (effettivamente dal 26/12/1791) - Come Canada Ovest=West Canada 23/07/1840-01/07/1867 (effettivo dal 5/02/1841) (unito al Canada Est nella PROVINCIA DEL CANADA) - Garantito Responsabilità di Governo 11/03/1848-1867 PROVINCIA 1/07/1867- Luogotenenti-Governatori GB 08/07/1792-10/04/1796 John GRAVES SIMCOE (1752+1806) 20/07/1796-17/08/1799 Peter RUSSELL (f.f.)(1733+1808) 17/08/1799-11/09/1805 Peter HUNTER (1746+1805) 11/09/1805-25/08/1806 Alexander GRANT (f.f.)(1734+1813) 25/08/1806-09/10/1811 Francis GORE (1°)(1769+1852) 09/10/1811-13/10/1812 Sir Isaac BROCK (f.f.)(1769+1812) 13/10/1812-19/06/1813 Sir Roger HALE SHEAFFE (f.f.)(1763+1851) 19/06/1813-13/12/1813 Francis DE ROTTENBURG, BARON DE ROTTENBURG (f.f.) (1757+1832) 13/12/1813-25/04/1815 Sir Gordon DRUMMOND (f.f.)(1771+1854) 25/04/1815-01/07/1815 Sir George MURRAY (Provvisorio)(1772-1846) 01/07/1815-21/09/1815 Sir Frederick PHILIPSE ROBINSON (Provvisorio)(1763+1852) 21/09/1815-06/01/1817 Francis GORE (2°) 11/06/1817-13/08/1818 Samuel SMITH (f.f.)(1756+1826) 13/08/1818-23/08/1828 Sir Peregrine MAITLAND (1777+1854) 04/11/1828-26/01/1836 Sir John COLBORNE (1778+1863) 26/01/1836-23/03/1838 Sir Francis BOND HEAD (1793+1875) 05/12/1837-07/12/1837