Education Quality in South Africa and Sub

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

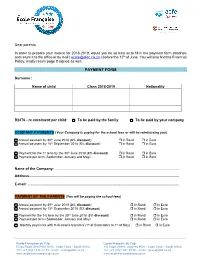

Payment Form Attached and Return It to the Office Or by Mail ( [email protected] ) Before the 12Th of June

Dear parents, In order to prepare your invoice for 2018-2019, would you be so kind as to fill in the payment form attached and return it to the office or by mail ( [email protected] ) before the 12th of June. You will also find the Financial Policy, kindly return page 8 signed as well. PAYMENT FORM Surname : Name of child Class 2018-2019 Nationality R2376 - re enrolment per child: To be paid by the family To be paid by your company COMPANY PAYMENTS (Your Company is paying for the school fees or will be reimbursing you) Annual payment by 30th June 2018 (8% discount) in Rand in Euro Annual payment by 15th September 2018 (5% discount) in Rand in Euro Payment for the 1st term by the 30th June 2018 (3% discount) in Rand in Euro Payment per term (September, January and May) in Rand in Euro Name of the Company: ............................................................................................................................ Address...................................................................................................................................................... E-mail: ....................................................................................................................................................... PAYMENT BY THE PARENTS (You will be paying the school fees) Annual payment by 30th June 2018 (8% discount) in Rand in Euro Annual payment by 15th September 2018 (5% discount) in Rand in Euro Payment for the 1st term by the 30th June 2018 (3% discount) in Rand in Euro Payment per -

School Leadership Under Apartheid South Africa As Portrayed in the Apartheid Archive Projectand Interpreted Through Freirean Education

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2021 SCHOOL LEADERSHIP UNDER APARTHEID SOUTH AFRICA AS PORTRAYED IN THE APARTHEID ARCHIVE PROJECTAND INTERPRETED THROUGH FREIREAN EDUCATION Kevin Bruce Deitle University of Montana, Missoula Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Deitle, Kevin Bruce, "SCHOOL LEADERSHIP UNDER APARTHEID SOUTH AFRICA AS PORTRAYED IN THE APARTHEID ARCHIVE PROJECTAND INTERPRETED THROUGH FREIREAN EDUCATION" (2021). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 11696. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/11696 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SCHOOL LEADERSHIP UNDER APARTHEID SCHOOL LEADERSHIP UNDER APARTHEID SOUTH AFRICA AS PORTRAYED IN THE APARTHEID ARCHIVE PROJECT AND INTERPRETED THROUGH FREIREAN EDUCATION By KEVIN BRUCE DEITLE Dissertation presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in International Educational Leadership The University of Montana Missoula, Montana March 2021 Approved by: Dr. Ashby Kinch, Dean of the Graduate School -

Apartheid Space and Identity in Post-Apartheid Cape Town: the Case of the Bo-Kaap

Apartheid Space and Identity in Post-Apartheid Cape Town: The Case of the Bo-Kaap DIANE GHIRARDO University of Southern California The Bo-Kaap district spreads out along the northeastern flanks of cheaper housing, they also standardized windows and doors and Signal Hill in the shadow of CapeTown's most significant topograplucal eliminated the decorative gables and parapets typical of hgher income feature, Table Mountain, and overlooks the city's business &strict. areas.7 While the some of the eighteenth century terraces exhibited Accordmg to contemporary hstorical constructions, the district includes typical Cape Dutch detads such as undulating parapets, two panel portals, four areas - Schotschekloof, Schoonekloof, Stadzicht and the Old and fixed upper sash and movable lower sash windows, the arrival of Malay Quarter, but none of these names appear on official maps (except the British at the end of the eighteenth century altered the style once Schotschekloof, which is the official name for the entire area).' The again. Typical elements of Georgian architecture such as slim windows, first three were named after the original farmsteads which were paneled double doors and fanlights, found their way into housing of all transformed into residential quarters, Schoonekloof having been social classes, includng the rental housing in the BO-K~~~.~At the end developed in the late nineteenth century and Schotschekloof and of the nineteenth century, new housing in the Bo-Kaap began to include Stadzicht during and immediately following World War 11.' pitched roofs, bay windows, and cast iron work on balconies and Schotschekloof tenements - monotonous modernist slabs - were verandahs, at a time when a larger number of houses also became the erected for Cape Muslims during the 1940s as housing to replace slums property of the occupant^.^ A dense network of alleys and narrow, leveled as a result of the 1934 Slum Act. -

Claude B. Ayo Chief Financial Officer, Enko Capital Claude Started His Career in 1991 with Ernst & Young France, Providing A

Claude B. Ayo Chief Financial Officer, Enko Capital Claude started his career in 1991 with Ernst & Young France, providing auditing, consulting, M&A and pre IPO services to international corporations in the banking, oil and gas and retail industries. In 2000, he returned to his home country and worked as an economic advisor and head of a national project at the ministry of economy and finance in Gabon. Claude joined the venture capital and private equity industry in 2008 and has since been living in South Africa, where he currently serves as the CFO of Enko Capital, a 50 million US Dollars fund focusing on Africa. Mr. Ayo holds a Bachelor degree from a French business school, an accounting qualification and an MBA degree from Harvard Business School. Philippe Bataille Director of the Indian Ocean Regional Office, Agence universitaire de la Francophonie Director of the office of the Indian Ocean AUF since March 2013, Philippe Bataille is an architect and doctor in urban geography. From 1997 to 2013 he was Director General of the National School of Architecture in Nantes (France). Within the same school, from 1990 to 1997, he was a teacher and researcher in a research laboratory, a laboratory which he contributed towards its creation. Before these functions in higher education, he worked as an architect in private agencies and public bodies . Christian Bellevenue Director of the local center of CIEP (Centre international d’études pédagogiques) in Reunion Island Christian Bellevenue is a senior executive of the French Ministry of National Education, Higher Education and Research. He was holding the position of an inspector in France for 10 years. -

A Neighborhood in Change

A neighborhood in change A case study on gentrification in Bo-Kaap, Cape Town Emilia Lundqvist & Matilda Pettersson Stadsbyggnad, stadsutveckling och planering / Urban Development and Planning. Kandidatuppsats, 20 HP Vårterminen 2020 Handledare: Defne Kadioglu 1 A special thanks to SIDA for providing us with a scholarship that made it possible for us to do our research in South Africa. Thanks to Hoai Anh Tran for supporting us when applying for the scholarship. And the biggest thanks to our supervisor Defne Kadioglu for providing us with much needed help during our difficult times. Our original plan was to do an 8 weeklong case study in Bo-Kaap, but because of Covid-19 and the impact that the pandemic has had on both the Swedish and the South African societies, this has affected our case study. We were forced to leave South Africa five weeks prior to our original plan. Because of this we had to make several of our interviews online which may have affected our end result. 2 Abstract When neighborhoods and cities fall in decline, cities and investors see an opportunity to turn the declining sites into profitable new projects, this happens all over the world in different renewal projects, or under the term gentrification. The outcome of gentrification can be considered to be both positive and negative, and the term is widely discussed in today's media. This study aims to get an understanding of how a small neighborhood in Cape Town called Bo-Kaap, that is famous for its rich culture and strong community, is affected by investors wanting to develop the neighborhood. -

DST-NRF Centre of Excellence “Birds As Keys to Biodiversity Conservation” Percy Fitzpatrick Institute, UCT

DST-NRF Centre of Excellence “Birds as Keys to Biodiversity Conservation” Percy FitzPatrick Institute, UCT ANNUAL REPORT 2013 Reporting Period 1 January - 31 December 2013 CONTENTS Page Executive Summary 2 Progress Report 4 Scientific research 4 Education and training 6 Information brokerage 8 Networking 12 Service rendering 15 Gender and equity impacts of research 20 Human Resources 23 Finances 26 Appendix 1 – Publications for 2013 31 Appendix 2 – Most cited PFIAO papers 44 CoE Identification Name of Director : Acting Director Assoc. Prof. Peter Ryan Name of CoE : DST-NRF Centre of Excellence at the Percy FitzPatrick Institute of African Ornithology Abbreviated CoE name : PFIAO CoE Host Institution : University of Cape Town Date completed : 3 March 2013 Page 1 of 45 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. Funding of the CoE for 2013 DST/NRF CoE funding for 2013 : 5,892,112 DST/NRF additional bursaries : 660,000 Carry forward from 2012 : 809,499 Interest earned during 2012 : 90,321 UCT URC support for the Pazvolski Chair in 2013 : 196,124* UCT URC support for Hotbirds project in 2013 : 355,000* UCT URC support for research page charges in 2013 : 40,561* Funding from other sources for the CoE in 2013 : 6,518,000** Total funding : R 12, 544,289 * represents UCT’s contribution to the CoE; R591 685 of R5 892 112 = 10.04% ** funding for CoE projects from sources other than the DST/NRF or UCT URC grants 2. Summary of progress against Five Key Performance Areas (i) Scientific Research A record 111 papers carrying the CoE address were published in peer-reviewed journals during 2013; 103 in impact factor rated journals and eight in non-rated journals, 38 in journals with an impact factor ≥3.5, 15 in journals with a rating ≥5 and five in journals with a rating ≥10. -

Advert Template

Western Cape Government Wes-Kaapse Regering PROVINCE OF THE WESTERN CAPE PROVINSIE WES-KAAP Provincial Gazette Provinsiale Koerant 7186 7186 Friday, 11 October 2013 Vrydag, 11 Oktober 2013 Registered at the Post Offıce as a Newspaper As ’n Nuusblad by die Poskantoor Geregistreer CONTENTS INHOUD (*Reprints are obtainable at Room M21, Provincial Legislature Building, (*Herdrukke is verkrygbaar by Kamer M21, Provinsiale Wetgewersgebou, 7 Wale Street, Cape Town 8001.) Waalstraat 7, Kaapstad 8001.) No. Page No. Bladsy Provincial Notices Provinsiale Kennisgewings 340 City of Cape Town Municipality (Table Bay District): 340 Stad Kaapstad Munisipaliteit (Tafelbaai-distrik): Wet op Removal of Restrictions Act............................................... 2710 Opheffing van Beperkings .................................................. 2710 341 City of Cape Town Municipality: Removal of Restrictions 341 Stad Kaapstad Munisipaliteit: Wet op Opheffing van Act....................................................................................... 2710 Beperkings .......................................................................... 2710 342 Cederberg Municipality: Removal of Restrictions Act ...... 2710 342 Cederberg Munisipaliteit: Wet op Opheffing van Beperkings. 2710 343 City of Cape Town Municipality (Tygerberg Region): 343 Stad Kaapstad Munisipaliteit (Tygerberg-streek): Wet op Removal of Restrictions Act............................................... 2711 Opheffing van Beperkings .................................................. 2711 344 -

The Effects of Gentrification and Sustainable Cultural Tourism Development in the Bo-Kaap, Cape Town

THE EFFECTS OF GENTRIFICATION AND SUSTAINABLE CULTURAL TOURISM DEVELOPMENT IN THE BO-KAAP, CAPE TOWN by MISHKAH BASSADIEN Dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Master of Technologiae: Tourism and Hospitality Management in the Faculty of Business and Management Sciences at the Cape Peninsula University of Technology Supervisor: Professor JP Spencer Cape Town Campus JANUARY 2017 CPUT copyright information The dissertation may not be published either in part (in scholarly, scientific or technical journals), or as a whole (as a monograph), unless permission has been obtained from the University. DECLARATION I, Mishkah Bassadien, student number 207154511, declare that the content of this research represents my own unaided work, and that the dissertation has not previously been submitted for academic examination towards any qualification. Furthermore, it represents my own opinions and not necessarily those of the Cape Peninsula University of Technology. ………………………………………… …………………………………….. MISHKAH BASSADIEN DATE ii ABSTRACT The study site is the Bo-Kaap area in Cape Town. Negative and positive changes within interrelated physical, social and economic spheres have resulted from gentrification, an urban development phenomenon. These changes need to be managed responsibly. This study problem sought to establish whether the traditional inhabitants of the Bo-Kaap are being replaced by a ‘new generation’ of inhabitants because of gentrification, and how negative and positive changes in the Bo-Kaap could be minimised and maximised respectively, through gentrification, by adopting a sustainable cultural tourism approach. A historical background of the Bo-Kaap reveals the history, culture and religion of this area, and highlights the special customs and traditions within the Bo-Kaap as potential areas of sustainable cultural tourism development to mitigate gentrification. -

Cape Town’S Creative Software Design and Development Sector

Digital gateway to Africa Cape Town’s Creative Software Design and Development sector Publication jointly compiled by Wesgro, City of Cape Town and PwC March 2013 ©Wesgro ©Wesgro 2 Digital Gateway to Africa March 2013 Foreword by the Executive Mayor of Cape Town It gives me great pleasure to present this publication to not only the people of Cape Town, but also South Africa and international investors and businesses. This unique publication on Cape Town’s Creative Software Design and Development sector, presents us with current trends and investment opportunities in the sector. The City of Cape Town collaborated with Wesgro and PwC in developing this brochure. We believe that partnerships like these are essential to achieve our goals of building, as articulated in the five key pillars of this administration namely; to build an opportunity city, a safe city, a caring city, an inclusive city and a well-run city. Information and Communications Technology (ICT) is one of the priority areas in the Integrated Development Plan. It is aligned to our goal of building an opportunity city that creates the enabling environment for economic growth and job creation to take place. It also has strong linkages to our plans to build a well-run city by using cutting edge technology to boost our capacity to deliver services efficiently. To this end the City is making considerable investment in infrastructure projects that will position Cape Town as a modern global city. These include the integrated rapid transport system that will, once completed, connect residents to centres and opportunities throughout the metro and the roll-out of broadband infrastructure that is expected to deliver major benefits to the economy of Cape Town. -

Ruan Hoffmann South Africa B. 1971 Education

“‘I was at high school in the eighties during Botha’s many States of Emergency [the National Party’s attempts to maintain power during the dying days of apartheid]. South Africa has always Been a highly charged and volatile environment to grow up and live in and I think that makes for interesting art.” Indifference, 2018 Earthenware, Ceramic Paperclay, underglaze, copper oxide and onglaze Ruan Hoffmann South Africa b. 1971 South African Born, Ruan Hoffmann originally studied art at the University of Pretoria Before emBarking on his artistic career. Using ceramic earthenware as his preferred medium, he chooses familiar objects such as plates, containers and tiles as his canvases, however the resulting works are not presented as homely pieces emanating from the domestic sphere But as willful, irregular and misshapen forms on which the artist’s unedited observations on life’s experiences flow in constant, noisy glimpses of thought. Ruan Hoffmann’s imagery ranges from classical engineering and Roman lettering, nature and self-portraiture to aBstraction and phallic forms. The mood can shift dramatically from anger, rage and provocation to humour, introspection and even vulnerability. The intent is to comment, confront and provoke. Hoffmann adorns the surfaces of his plates with a vast array of images and text that can Be unapologetic, politically confrontational, improper and even sometimes rude. It is work that fuses the contemporary criticality of art with the wantonly sensual aesthetics of making. It is unashamedly loud, uncompromising -

Lessons from Madiba

International Boys' IBSC Schools Coalition LESSONS FROM MADIBA INTERNATIONAL BOYS’ SCHOOLS CAO LITION 22ND ANNUAL CONFERENCE BISHOPS | CAPE TOWN | 7 – 10 JULY 2015 BISHOPS RONDEBOSCH SA COLLEGE WYNBERG WP COLLEGE AND PREP BOYS’ SCHOOL JUNIOR AND HIGH SCHOOLS BOYS’ HIGH AND JUNIOR SCHOOLS PREPARATORY CONFERENCE AT A GLANCE Day 1 Day 2 Day 3 Day 4 Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday 07 08 09 10 July July July July 12:30 – 2:30 PM 9:00 – 10:15 AM 9:00 – 10:15 AM 9:00 – 10:00 AM Registration Plenary Session Morning Plenary Indaba 6 featuring Keynote Session and Keynote Details, page 57 1:15 – 2:30 PM Speaker: Judge Edwin Speaker featuring Gourmet ‘Boerie’ Rolls Cameron Dr Wilhelm Verwoerd 10:00 – 10:45 AM Details, page 12 Details, page 13 Tea 3:00 – 5:00 PM Conference Plenary 10:15 – 10:45 AM 10:15 – 10:45 AM 11:00 AM – 12:30 PM Opening and Keynote Tea Tea Closing Plenary Speakers: Archbishop Ceremony and 10:45 – 11:45 AM Emeritus Desmond 11:00 AM – 12:30 PM Keynote Speaker Indaba 1 Tutu and Professor Indaba 4 Mr Rory Steyn Details, page 17 Khalil Osiris Details, page 39 Details, page 13 Details, page 11 12 NOON – 1:00 PM 12:30 – 1:45 PM 12:30 PM Indaba 2 Lunch 5:00 – 6:30 PM Buses leave for hotels Details, page 19 South African Heads Sampling of Constantia and airport Lunch Valley Wines 1:00 – 1:45 PM Details, page 57 Lunch 2:00 – 3:00 PM 6:00 – 8:00 PM New IBSC Members Indaba 5 Supper on campus Reception Details, page 46 2:00 – 3:00 PM Indaba 3 3:15 – 5:15 PM Details, page 34 Buses depart for a celebratory wine 3:00 – 3:45 PM tasting at Groot Tea Constantia Wine Farm Details, page 38 3:45 PM – 5:15 PM Plenary Session 5:30 – 6:00 PM featuring IBSC Annual Scenic drive from Business Meeting and Constantia, via Keynote Speaker Atlantic Coast, to Ms Suzie Nkambule Waterfront Details, page 12 6:30 PM 5:30 PM Dinner at the Home Dinner with Waterfront Cape Town Educators Details, page 38 or free time • The schedule and all conference information are subject to change. -

The Cost of the Cup: a Case Study on the Political and Economic Impacts

University of Pennsylvania Masthead Logo ScholarlyCommons CUREJ - College Undergraduate Research College of Arts and Sciences Electronic Journal 4-2019 The oC st of the Cup: A Case Study on the Political and Economic Impacts of Hosting Mega Sporting Events George J. Avdellas University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/curej Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Avdellas, George J., "The osC t of the Cup: A Case Study on the Political and Economic Impacts of Hosting Mega Sporting Events" 01 April 2019. CUREJ: College Undergraduate Research Electronic Journal, University of Pennsylvania, https://repository.upenn.edu/curej/222. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/curej/222 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The oC st of the Cup: A Case Study on the Political and Economic Impacts of Hosting Mega Sporting Events Abstract In the modern world, sports have become a new form of geopolitical signaling. Countries who are entrusted with hosting mega sporting events, from the Olympic Games to the World Cup are seen as capable and competent nations. For developing nations, these games can bring political legitimacy, as it shows that their respective teams can not only compete in global events, but their governments can host safe, secure, and well run events. In this thesis, I will be examining South Africa’s process in bidding, building and hosting the 2010 World Cup and the subsequent political and economic effects. South Africa was able to leverage the World Cup, as the first African nation to host a major international sporting event, to gain not only regional signaling—as it is still the only African nation to host one of these events—but place itself in the international spotlight and gain geopolitical legitimacy through its successful event.