Gendarmeries in Denmark Through History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abstract @On Ita (17 Dic

RETE OPERATIVA @ON PER IL CONTRASTO AI GRUPPI CRIMINALI ORGANIZZATI MAFIA-STYLE ________________________________________________________________________________ ABSTRACT 1. PREMESSA La DIA sta sostenendo con sempre maggior impegno l’azione di contrasto internazionale alle mafie , non solo sul piano operativo, ma anche attraverso una più energica opera di sensibilizzazione degli omologhi stranieri finalizzata a dare nuova e rafforzata consapevolezza del fenomeno transnazionale della criminalità organizzata e di quella di tipo mafioso. In tale contesto, è stato ritenuto necessario perfezionare, nel corso del Semestre italiano di Presidenza del Consiglio Europeo, uno strumento che integrasse a livello operativo gli strumenti di cooperazione di polizia già esistenti. Al riguardo, il Consiglio GAI 1 in data 4 dicembre 2014, su iniziativa italiana ha approvato l’istituzione della Rete Operativa Antimafia @ON. 2. COS’È @ON La Rete @ON , in collaborazione con Europol, rende possibile l’impiego sul posto di investigatori specializzati 2 delle Forze di Polizia aderenti al Network, per il contrasto delle organizzazioni criminali “gravi” e mafia-style presenti nell’Unione Europea e non, favorendo lo scambio di buone prassi ed il necessario rapporto fiduciario. I gruppi criminali attenzionati sono principalmente italiani, di etnia albanese, euroasiatici, bande di motociclisti, ma anche quelli emergenti (mafie nigeriane, cinesi, turche, ecc.) che pongono un serio rischio per la sicurezza e l’economia dell’U.E. La Rete @ON ed il suo progetto di finanziamento europeo denominato ONNET , si basano su un network di Paesi e su un “Core Group” (Italia, Francia, Germania, Spagna, Belgio e Paesi Bassi ) che funge da cabina di regia per la selezione delle investigazioni da supportare. -

General Information Pursuant to Section 55 of the Federal Data

General information pursuant to Section 55 of the Federal Data Protection Act (Bundesdatenschutzgesetz - BDSG) regarding data processing by customs authorities in the context of criminal offences and infringements of rules of law (Last updated: December 2018) Preface Among the functions of Customs are the prevention, detection, investigation and prosecution of certain offences and infringements of rules of law including the enforcement of the fines imposed by the customs authorities. In order to fulfil this role, the customs services are entitled to process personal data. The information detailed in this letter concerns: • Controls under aspects of customs and movement of cash law • Procedures concerning tax-related criminal offences and infringements of rules of law • Procedures concerning criminal offences and infringements in non-tax relevant areas (excluding the Financial Monitoring Unit to Control Unreported or Illicit Employment) The information contained herein only concerns the processing of personal data by the customs authorities (main customs offices, customs investigation offices, the German Customs Criminological Office, the Federal Treasury and its branches, and the General Customs Directorate). Data processing by the tax administration (tax offices, regional finance directorates, state offices for finance, Federal Central Tax Office) is not addressed. “Personal data” means any information that directly relates to an identified or identifiable natural person. When financial authorities “process” personal data, it means that they collect, save, apply, transfer, make available for retrieval, edit or delete data. In the following we will provide information about the kind of personal data that we collect, who we collect it from, and what we do with this data. In addition, we will inform you about your privacy rights in relation to data protection and advise you on whom to contact if you have any questions or complaints. -

The AFP Is Well Informed of the Criminal Practices and Illicit Trading Taking Place on the Dark Web

The AFP is well informed of the criminal practices and illicit trading taking place on the dark web. We are working with our partners to combat all forms of technology-enabled crime. In recent years there has been a steady increase in the number of seizures of all drug types via the mail system detected at the Australian border. High frequency-low volume importations such as ones through our mail system pose a considerable cumulative threat. These shipments contribute towards supplying the Australian market and exacerbate social problems within Australia associated with drug harm. Seizing these smaller importations can impact on disrupting the drug trade. The AFP and other Australian law enforcement agencies are well aware of this method of drug importation and are committed to targeting and combating it. The AFP works alongside its partner agencies on this matter, including Border Force and state and territory police. While it is not an offence to access websites that provide access to sellers of illegal substances, it is an offence to import or attempt to import a border controlled drug including synthetic drugs into Australia purchased from such a website. Offenders should be aware that if they seek to import illicit and synthetic drugs they will be subject of law enforcement scrutiny and investigation. Recently, a national co-ordinated policing campaign focused on detecting drugs being distributed via the Australian postal service saw a total of 62 illicit drugs or illegally obtained prescription medications seized by police. Operation Vitreus was co-ordinated by the National Methylamphetamine Strategy Group, which is currently lead by SA Police (SAPOL), but involved all State and Territory police agencies, working in conjunction with the Australian Federal Police, Australian Border Force (ABF), the Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission and AUSTRAC. -

Status of the Baltic/Wadden Sea Population of the Common Eider Somateria M

Baltic/Wadden Sea Common Eider 167 Status of the Baltic/Wadden Sea population of the Common Eider Somateria m. mollissima M. Desholm1, T.K. Christensen1, G. Scheiffarth2, M. Hario3, Å. Andersson4, B. Ens5, C.J. Camphuysen6, L. Nilsson7, C.M. Waltho8, S-H. Lorentsen9, A. Kuresoo10, R.K.H. Kats5,11, D.M. Fleet12 & A.D. Fox1 1Department of Coastal Zone Ecology, National Environmental Research Institute, Grenåvej 12, 8410 Rønde, Denmark. Email: [email protected]/[email protected]/[email protected] 2Institut für Vogelforschung, ‘Vogelwarte Helgoland’, An der Vogelwarte 21, D - 26386 Wilhelmshaven, Germany. Email: [email protected] 3Finnish Game and Fisheries Research Institute, Söderskär Game Research Station. P.O.Box 6, FIN-00721 Helsinki, Finland. Email: [email protected] 4Ringgatan 39 C, S-752 17 Uppsala, Sweden. Email: [email protected] 5Alterra, P.O. Box 167, 1790 AD Den Burg, Texel, The Netherlands. Email:[email protected]/[email protected] 6Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research (Royal NIOZ), P.O. Box 59, 1790 AB Den Burg, Texel, The Netherlands. Email: [email protected] 7Department of Animal Ecology, University of Lund, Ecology Building, S-223 62 Lund, Sweden. Email: [email protected] 873 Stewart Street, Carluke, Lanarkshire, Scotland, UK, ML8 5BY. Email: [email protected] 9Norwegian Institute for Nature Research. Tungasletta 2, N-7485 Trondheim, Norway Email: [email protected] 10Institute of Zoology and Botany, Riia St. 181, 51014, Tartu, Estonia. Email: [email protected] 11Department of Animal Ecology, University of Groningen, Kerklaan 30, 9751 NH, Groningen, The Netherlands. -

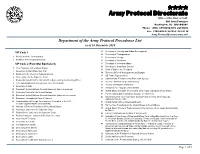

Army Protocol Directorate

Army Protocol Directorate Office of the Chief of Staff 204 Army Pentagon Washington, DC 20310-0204 Phone: (703) 697-0692/DSN 227-0692 Fax: (703)693-2114/DSN 223-2114 [email protected] Department of the Army Protocol Precedence List as of 10 December 2010 VIP Code 1 27 Secretary of Housing and Urban Development 28 Secretary of Transportation 1 President of the United States 29 Secretary of Energy 2 Heads of State/Reigning Royalty 30 Secretary of Education VIP Code 2 (Four Star Equivalent) 31 Secretary of Veterans Affairs 32 Secretary of Homeland Security 3 Vice President of the United States 33 Chief of Staff to the President 4 Governors in Own State (see #42) 34 Director, Office of Management and Budget 5 Speaker of the House of Representatives 35 US Trade Representative 6 Chief Justice of the Supreme Court 36 Administrator, Environmental Protection Agency 7 Former Presidents of the United States (by seniority of assuming office) 37 Director, National Drug Control Policy 8 U.S. Ambassadors to Foreign Governments (at post) 38 Director of National Intelligence 9 Secretary of State 39 President Pro Tempore of the Senate 10 President, United Nations General Assembly (when in session) 40 United States Senators (by seniority; when equal, alphabetically by State) 11 Secretary General of the United Nations 41 Former United States Senators (by date of retirement) 12 President, United Nations General Assembly (when not in session) 42 Governors when not in own State (by State date of entry; when equal by 13 President, International Court of Justice alphabetically) (see #4) 14 Ambassadors to Foreign Governments Accredited to the U.S. -

Forze Di Polizia, Forze Armate E Capitanerie Di Porto

9 dicembre 2020 Censimento permanente delle Istituzioni Pubbliche: Forze di polizia, Forze armate e Capitanerie di porto. Anni 2015 e 2017 I censimenti permanenti della popolazione e delle unità economiche rappresentano un’importante innovazione nell’ambito della statistica ufficiale, fino al 2011 caratterizzata da censimenti generali a cadenza decennale. Quelli effettuati sulle unità economiche sono accomunati dalla medesima strategia e si basano su due elementi cardine: l’uso di un registro statistico, realizzato dall’Istat attraverso l’integrazione di diverse fonti amministrative e statistiche e aggiornato annualmente; una rilevazione diretta a forte valenza tematica, necessaria a completare, a cadenza periodica (per le istituzioni pubbliche biennale e dalla prossima edizione triennale; per imprese e istituzioni non profit triennale), il quadro informativo e consentire l’analisi in serie storica del profilo di istituzioni pubbliche, imprese e istituzioni non profit. La strategia censuaria prevede, a regime, che negli anni non coperti da rilevazione diretta il rilascio dei dati sia di fonte registro. Nel 2016, l’Istat ha avviato la prima edizione del Censimento permanente delle istituzioni pubbliche (data di riferimento 31/12/2015)1, basato sull’integrazione del Registro di base delle istituzioni pubbliche con le informazioni desunte dall’indagine statistica diretta. Da quest’ultima sono state escluse le scuole statali (oltre 40mila), vista la disponibilità di informazioni di fonte amministrativa. L’indagine diretta a supporto del Registro delle istituzioni pubbliche si basa su una parte di informazioni core, da acquisire con continuità, e su un set di informazioni di approfondimento da raccogliere a cadenza pluriennale. Rispetto al precedente Censimento generale a cadenza decennale, il Censimento permanente delle istituzioni pubbliche ha esteso la rilevazione2 a Forze di polizia, Forze armate e Capitanerie di porto, secondo specifiche modalità condivise in accordo con i Ministeri competenti. -

Trafficking in Human Beings

TemaNord 2014:526 TemaNord Ved Stranden 18 DK-1061 Copenhagen K www.norden.org Trafficking in Human Beings Report from a conference on Identification of victims and criminals Trafficking in Human Beings – why we do not notice them In the Nordic countries, most of the reported cases of trafficking in human beings today concern women and girls trafficked for sexual exploitation, but experiences from Europe indicate that human trafficking has increased also in farming, household work, construction, and house building, as well as in begging, shoplifting and thefts. The conference Identification of victims and criminals – why we do not notice them on 30–31 May 2013 in Tallinn, Estonia formed the conclusion of a Nordic-Baltic-Northwest Russian cooperation project. Around 80 participants attended the two-day conference to discuss ways of identifying victims and criminals and to find answer to the question of why we do not notice victims or criminals, even though we now have available to us facts, figures, research and knowledge about human trafficking as a part of international organized crime. TemaNord 2014:526 ISBN 978-92-893-2767-1 ISBN 978-92-893-2768-8 (EPUB) ISSN 0908-6692 conference proceeding TN2014526 omslag.indd 1 09-04-2014 07:18:39 Trafficking in Human Beings Report from a conference on Identification of victims and criminals – why we do not notice them TemaNord 2014:526 Trafficking in Human Beings Report from a conference on Identification of victims and criminals - why we do not notice them ISBN 978-92-893-2767-1 ISBN 978-92-893-2768-8 (EPUB) http://dx.doi.org/10.6027/TN2014-526 TemaNord 2014:526 ISSN 0908-6692 © Nordic Council of Ministers 2014 Layout: Hanne Lebech Cover photo: Beate Nøsterud Photo: Reelika Riimand Print: Rosendahls-Schultz Grafisk Copies: 516 Printed in Denmark This publication has been published with financial support by the Nordic Council of Ministers. -

Tilley Award 2005

Tilley Award 2005 Application form The following form must be competed in full. Failure to do so will result in disqualification from the competition. Please send competed application forms to Tricia Perkins at [email protected] All entries must be received by noon on the 29 April 2005. Entries received after that date will not be accepted under any circumstances. Any queries on the application process should be directed to Tricia Perkins on 0207 035 0262. 1. Details of application Title of the project ‘The Human Chassis Number’ Name of force/agency/CDRP: Hertfordshire Constabulary – Central Area Road Policing Tactical Team Name of one contact person with position/rank (this should be one of the authors): Sergeant Greg O’Toole 742 Email address: greg.o’[email protected] Full postal address: Welwyn Garden City Police station The Campus Welwyn Garden City Hertfordshire AL8 6AF Telephone number: 01707 - 638035 Fax number 01707 638009 Name of endorsing senior representatives(s) Simon Ash Position and rank of endorsing senior representatives(s) Deputy Chief Constable Full address of endorsing senior representatives(s) Hertfordshire Police Headquarters Stanborough Road Welwyn Garden City Hertfordshire AL8 6XF 2. Summary of application 1 ‘THE HUMAN CHASSIS NUMBER’ SCANNING In September 2003, Hertfordshire Constabulary set up a road policing team to proactively target criminals using motor vehicles to commit crime. The team found that the potential benefit of Automatic Number-Plate Recognition (ANPR) technology was not being fully realised due to technical limitations. There was no capability to link intelligence, on the national ANPR databases, with known individuals in the absence of a number-plate match. -

The Bosnian Train and Equip Program: a Lesson in Interagency Integration of Hard and Soft Power by Christopher J

STRATEGIC PERSPECTIVES 15 The Bosnian Train and Equip Program: A Lesson in Interagency Integration of Hard and Soft Power by Christopher J. Lamb, with Sarah Arkin and Sally Scudder Center for Strategic Research Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University The Institute for National Strategic Studies (INSS) is National Defense University’s (NDU’s) dedicated research arm. INSS includes the Center for Strategic Research, Center for Complex Operations, Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs, Center for Technology and National Security Policy, and Conflict Records Research Center. The military and civilian analysts and staff who comprise INSS and its subcomponents execute their mission by conducting research and analysis, publishing, and participating in conferences, policy support, and outreach. The mission of INSS is to conduct strategic studies for the Secretary of Defense, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the unified com- batant commands in support of the academic programs at NDU and to perform outreach to other U.S. Government agencies and the broader national security community. Cover: President Bill Clinton addressing Croat-Muslim Federation Peace Agreement signing ceremony in the Old Executive Office Building, March 18, 1994 (William J. Clinton Presidential Library) The Bosnian Train and Equip Program The Bosnian Train and Equip Program: A Lesson in Interagency Integration of Hard and Soft Power By Christopher J. Lamb with Sarah Arkin and Sally Scudder Institute for National Strategic Studies Strategic Perspectives, No. 15 Series Editor: Nicholas Rostow National Defense University Press Washington, D.C. March 2014 Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the contributors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Defense Department or any other agency of the Federal Government. -

NATO ARMIES and THEIR TRADITIONS the Carabinieri Corps and the International Environment by LTC (CC) Massimo IZZO - LTC (CC) Tullio MOTT - WO1 (CC) Dante MARION

NATO ARMIES AND THEIR TRADITIONS The Carabinieri Corps and the International Environment by LTC (CC) Massimo IZZO - LTC (CC) Tullio MOTT - WO1 (CC) Dante MARION The Ancient Corps of the Royal Carabinieri was instituted in Turin by the King of Sardinia, Vittorio Emanuele 1st by Royal Warranty on 13th of July 1814. The Carabinieri Force was Issued with a distinctive uniform in dark blue with silver braid around the collar and cuffs, edges trimmed in scarlet and epaulets in silver, with white fringes for the mounted division and light blue for infantry. The characteristic hat with two points was popularly known as the “Lucerna”. A version of this uniform is still used today for important ceremonies. Since its foundation Carabinieri had both Military and Police functions. In addition they were the King Guards in charge for security and honour escorts, in 1868 this task has been given to a selected Regiment of Carabinieri (height not less than 1.92 mt.) called Corazzieri and since 1946 this task is performed in favour of the President of the Italian Republic. The Carabinieri Force took part to all Italian Military history events starting from the three independence wars (1848) passing through the Crimean and Eritrean Campaigns up to the First and Second World Wars, between these was also involved in the East African military Operation and many other Military Operations. During many of these military operations and other recorded episodes and bravery acts, several honour medals were awarded to the flag. The participation in Military Operations abroad (some of them other than war) began with the first Carabinieri Deployment to Crimea and to the Red Sea and continued with the presence of the Force in Crete, Macedonia, Greece, Anatolia, Albania, Palestine, these operations, where the basis leading to the acquirement of an international dimension of the Force and in some of them Carabinieri supported the built up of the local Police Forces. -

Combating Political Violence Movements with Third-Force Options Doron Zimmermann ∗

Between Minimum Force and Maximum Violence: Combating Political Violence Movements with Third-Force Options Doron Zimmermann ∗ Introduction: Balancing the Tools of Counter-Terrorism In most liberal democratic states it is the responsibility of the police forces to cope with “internal” threats, including terrorism, since in such states terrorism is invariably defined as a criminal act rather than a manifestation of insurgent political violence. In many such instances, the resultant quantitative and qualitative overtaxing of law en- forcement capabilities to keep the peace has led to calls by sections of the public, as well as by the legislative and executive branches of government, to expand both the le- gal and operational means available to combat terrorism, and to boost civilian agen- cies’ capacity to deal with terrorism in proportion to the perceived threat. The deterio- rating situation in Ulster in Northern Ireland between 1968 and 1972 and beyond is an illustrative case in point.1 Although there have been cases of successfully transmogrifying police forces into military-like formations, the best-known and arguably most frequent example of aug- mented state responses to the threat posed by insurgent political violence movements is the use of the military in the fight against terrorism and in the maintenance of internal security. While it is imperative that the threat of a collapse of national cohesion due to the overextension of internal civil security forces be averted, the deployment of all branches of the armed forces against a terrorist threat is not without its own pitfalls. Paul Wilkinson has enunciated some of the problems posed by the use of counter-ter- rorism military task forces, not the least of which is that [a] fully militarized response implies the complete suspension of the civilian legal system and its replacement by martial law, summary punishments, the imposition of curfews, military censorship and extensive infringements of normal civil liberties in the name of the exigencies of war. -

Border Management Reform in Transition Democracies

Border Management Reform in Transition Democracies Editors Aditya Batara G Beni Sukadis Contributors Pierre Aepli Colonel Rudito A.A. Banyu Perwita, PhD Zoltán Nagy Lieutenant-Colonel János Hegedűs First Edition, June 2007 Layout Front Cover Lebanese-Israeli Borders Downloaded from: www.michaelcotten.com Printed by Copyright DCAF & LESPERSSI, 2007 The Geneva Centre for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces FOREWORD Suripto, SH Vice Chairman of 3rd Commission, Indonesian House of Representatives And Chariman of Lesperssi Founder Board Border issues have been one of the largest areas of concern for Indonesia. Since becoming a sovereign state 61 years ago, Indonesia is still facing a series of territorial border problems. Up until today, Indonesia has reached agreements with its neighbouring countries related to demarcation and state border delineation. However, the lack of an unequivocal authority for border management has left serious implications for the state’s sovereignty and its citizen’s security. The Indonesian border of today, is still having to deal with border crime, which includes the violation of the territorial border, smuggling and terrorist infiltration, illegal fishing, illegal logging and Human Rights violations. These kinds of violations have also made a serious impact on the state’s sovereignty and citizen’s security. As of today, Indonesia still has an ‘un-settled’ sea territory, with regard to the rights of sovereignty (Additional Zone, Economic Exclusive Zone, and continent plate). This frequently provokes conflict between the authorised sea-territory officer on patrol and foreign ships or fishermen from neighbouring countries. One of the principal border problems is the Sipadan-Ligitan dispute between Indonesia and Malaysia, which started in 1969.