Art History Specimen Booklet Front Pages.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Summons of Death on the Medieval and Renaissance English Stage

The Summons of Death on the Medieval and Renaissance English Stage The Summons of Death on the Medieval and Renaissance English Stage Phoebe S. Spinrad Ohio State University Press Columbus Copyright© 1987 by the Ohio State University Press. All rights reserved. A shorter version of chapter 4 appeared, along with part of chapter 2, as "The Last Temptation of Everyman, in Philological Quarterly 64 (1985): 185-94. Chapter 8 originally appeared as "Measure for Measure and the Art of Not Dying," in Texas Studies in Literature and Language 26 (1984): 74-93. Parts of Chapter 9 are adapted from m y "Coping with Uncertainty in The Duchess of Malfi," in Explorations in Renaissance Culture 6 (1980): 47-63. A shorter version of chapter 10 appeared as "Memento Mockery: Some Skulls on the Renaissance Stage," in Explorations in Renaissance Culture 10 (1984): 1-11. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Spinrad, Phoebe S. The summons of death on the medieval and Renaissance English stage. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. English drama—Early modern and Elizabethan, 1500-1700—History and criticism. 2. English drama— To 1500—History and criticism. 3. Death in literature. 4. Death- History. I. Title. PR658.D4S64 1987 822'.009'354 87-5487 ISBN 0-8142-0443-0 To Karl Snyder and Marjorie Lewis without who m none of this would have been Contents Preface ix I Death Takes a Grisly Shape Medieval and Renaissance Iconography 1 II Answering the Summon s The Art of Dying 27 III Death Takes to the Stage The Mystery Cycles and Early Moralities 50 IV Death -

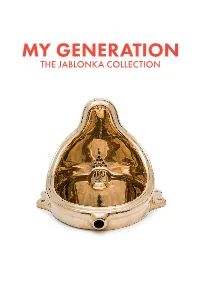

My Generation the Jablonka Collection

MY GENERATION THE JABLONKA COLLECTION Exhibition Facts Duration 2 October 2020 – 21 February 2021 Venue Bastion Hall & Colonade Hall Curators Rafael Jablonka Elsy Lahner, ALBERTINA Works ca. 110 Catalogue Available for EUR 32.90 (English & German) onsite at the Museum Shop as well as via www.albertina.at Contact Albertinaplatz 1 | 1010 Vienna T +43 (01) 534 83 0 [email protected] www.albertina.at Opening Hours Daily 10 am – 6 pm Wednesdays & Fridays 10 am – 9pm Press contact Fiona Sara Schmidt T +43 (01) 534 83 511 | M +43 (0)699 12178720 [email protected] Sarah Wulbrandt T +43 (01) 534 83 512 | M +43 (0)699 10981743 [email protected] My Generation The Jablonka Collection 2 October 2020 – 21. February 2021 With this exhibition, the Albertina Museum presents the most recent addition to its holdings: the collection of Rafael and Teresa Jablonka, which, comprising more than 400 works, ranks among the most distinguished collections of American and German art of the 1980s. Rafael Jablonka was born in Poland in 1952. After moving to Germany and taking the detour of working as an exhibition curator, he subsequently founded Galerie Jablonka with venues in Cologne, Berlin, and Zurich, eventually turning from a renowned art dealer into an important and passionate collector. Featuring, among others, Francesco Clemente, Roni Horn, Mike Kelley, Sherrie Levine, and Andreas Slominski, the Jablonka Collection includes artists with whom Rafael Jablonka has worked over the years, whom he promoted, and some of whom he discovered. However, he also collected works by artists beyond the program of his gallery—artists he greatly admired and whose works he ultimately wished to conserve for posterity. -

Skulls in 1499, When He Jim Dine: Pop Artist

1. Skull Symbolism in Art History 3. Leonardo da Vinci & Anatomy 5. Artists’ use of a Skull: Key words This drawing dates from around 1510, although Leonardo (highlighted) Vanitas had first started looking at human skulls in 1499, when he Jim Dine: Pop artist. Repeatedly uses the The term originally comes from the opening got access to human cadavers from the hospital of Santa skull to find different emotions to lines of the Book of Ecclesiastes in the Bible: Maria Novella in Florence. He used innovative techniques, express. Certain pieces feel foreboding, ‘Vanity of vanities, all is vanity.’ Vanitas are such as injecting molten wax, to locate and draw the cavities while others evoke calmness, sadness, LINK closely related to memento mori still lifes around the brain in the bones of the cranium. playfulness and even joy. which are artworks that remind the viewer of He was keen to find the seat the shortness and fragility of life (memento Extended of the human soul. The spine Pablo Picasso: Picasso was superstitious mori is a Latin phrase meaning ‘remember was thought to be the most Reading about death. He kept a skull in his studio you must die’) and include symbols such as likely location. Leonardo and had included human or animal skulls skulls and extinguished candles. However showed that the brain and in his work as early as 1908. vanitas still-lifes also include other symbols spine were connected but such as musical instruments, wine and books never identified where the Human anatomy is the study of to remind us explicitly of the vanity (in the LINK human soul lies. -

Harvard Fall Tournament XIII Edited by Jon Suh with Assistance From

Harvard Fall Tournament XIII Edited by Jon Suh with assistance from Raynor Kuang, Jakob Myers, and Michael Yue Questions by Jon Suh, Michael Yue, Ricky Li, Kelvin Li, Robert Chu, Alex Cohen, Kevin Huang, Justin Duffy, Raynor Kuang, Chloe Levine, Jakob Myers, Thomas Gioia, Erik Owen, Michael Horton, Luke Minton, Olivia Murton, Conrad Oberhaus, Jiho Park, Alice Sayphraraj, Patrick Magee, and Eric Mukherjee Special thanks to Will Alston, Jordan Brownstein, Robert Chu, Stephen Eltinge, and Olivia Murton Round 5 Tossups 1. The English version of this art form was developed by Marie Rambert and Ninette de Valois and takes influence from the Cecchetti [“chih-KET-ee ”] method, while other variations of it include the Bournonville and Vaganova. Sissones [“SEE-sohns”] in this art form can be done both ouverte or fermé, meaning ‘open’ or ‘closed.’ Cesare Negri established this art form’s (*) five fundamental positions, and its Balanchine style predominates its neoclassical form. A pas de deux [“pah duh douh”] in this art form is a duet, and a grand jeté [“grahn zuht”] in it is a leap with legs extended. In the en pointe [“on point”] stance in this performance art, the dancer stands on the tips of their toes. For 10 points, name this dance form often performed in a tutu. ANSWER: ballet [Ed’s note: The original writer worded it “For 10 pointes.”] <Sayphraraj> 2. Dividing the total curvature of an immersed path by twice this number yields the turning number. Barbier’s theorem states that all Reuleaux polygons have perimeter equal to width multiplied by this number. -

To the Ottoman Turks

DECLINE AND FALL OF BYZANTIUM TO THE OTTOMAN TURKS BY DOUKAS An Annotated Translation of "Historia Turco-Byzantine" by Harry I Magoulias, Wayne State University Wayne State University Press Detroit 1975 C y 2Wa.yAn iuersit ess, Detroit,, Micchigan5482 rightsarereserved No part of this book naybe reproduced without formal permission. Library of Congress Catalogingin Publication Data Ducas, fl. 1455. Decline and fall of Byzantium tothe Ottoman Turks. First ed. published under title:Historia Byzantina. Bibliography: P. Includes index. 1. Byzantine Empire History.2. TurkeyHistory-1288-1453 A2D813Magot949.5 Harry 75 9949 itle. DF631 ISBN 0-8143-1540-2 To Ariadne vuvevvoc KaX4 re Kl 7aO7 CONTENTS Chronology 9 Introduction 23 Decline and Fall of Byzantium to the Ottoman Turks 55 Notes 263 Bibliography 325 Index 331 7 ILLUSTRATIONS Old City of Rhodes 42 John VI Kantakouzenos 43 Manuel II Palaiologos 44 Emperor John VIII Palaiologos 45 Monastery of Brontocheion, Mistra 46 Palace of Despots, Mistra 47 Walls of Constantinople 48 Walls of Constantinople with Moat 49 Mehmed H the Conqueror 50 Emperor Constantine XI 51 MAPS The Byzantine World Before the Fall 1453 52 Greece and Western Anatolia Before the Fall 1453 53 Constantinople 54 8 CHRONOLOGY CHAPTER I page 57 Listing of the years and generations from Adam to the Fourth Crusade, 12 April 1204. CHAPTER II page 59 Reigns of the emperors of Nicaea to the recapture of Constantinople in 1261. Conquests of the Seljuk Turks and appearance of the Ottomans. Reigns of Andronikos II and Michael IX, Andronikos III, John V and John VI Kantakouze- nos. Turks occupy Gallipoli (1354). -

University of Pardubice Faculty of Arts and Philosophy the Poetics Of

University of Pardubice Faculty of Arts and Philosophy The Poetics of Robert Blair Antonín Mrvík Thesis 2010 Prohlašuji: Tuto práci jsem vypracoval samostatně. Veškeré literární prameny a informace, které jsem v práci využil, jsou uvedeny v seznamu použité literatury. Byl jsem seznámen s tím, že se na moji práci vztahují práva a povinnosti vyplývající ze zákona č. 121/2000 Sb., autorský zákon, zejména se skutečností, že Univerzita Pardubice má právo na uzavření licenční smlouvy o užití této práce jako školního díla podle § 60 odst. 1 autorského zákona, a s tím, že pokud dojde k užití této práce mnou nebo bude poskytnuta licence o užití jinému subjektu, je Univerzita Pardubice oprávněna ode mne požadovat přiměřený příspěvek na úhradu nákladů, které na vytvoření díla vynaložila, a to podle okolností až do jejich skutečné výše. Souhlasím s prezenčním zpřístupněním své práce v Univerzitní knihovně Univerzity Pardubice. V Pardubicích dne 25.06 . 2010 Antonín Mrvík Acknowledgements: I would like to express my undying gratitude to prof. PhDr. Bohuslav Mánek, CSc. for all his time, valuable advice and encouraging support. Special thanks to my family and friends for their continued encouragement and support. ABSTRACT The aim of this work is to provide and summarize the information about the life, work, and poetics of the Reverend Robert Blair, with particular stress placed on his poem of renown, ―The Grave‖. The first part focuses on introducing the reader to the historical contexts of the times of Robert Blair, and is accompanied by a compiled biography of the poet, along with a short account of his most prominent friends and acquaintances. -

MARTIN-DISSERTATION.Pdf (538.7Kb)

DAPHNE IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY: THE GROTESQUE IN MODERN POETRY A Dissertation by THOMAS HENRY MARTIN Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2008 Major Subject: English DAPHNE IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY: THE GROTESQUE IN MODERN POETRY A Dissertation by THOMAS HENRY MARTIN Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved by: Chair of Committee, Paul Christensen Richard Golsan M. Jimmie Killingsworth Janet McCann Head of Department, M. Jimmie Killingsworth May 2008 Major Subject: English iii ABSTRACT Daphne in the Twentieth Century: The Grotesque in Modern Poetry. (May 2008) Thomas Henry Martin, B.A., The University of Texas at Austin; M.A., Texas A&M University Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. Paul Christensen This dissertation seeks to expose the importance of the grotesque in the poetry and writings of Trans-Atlantic poets of the early twentieth century, particularly Ezra Pound, H.D., William Carlos Williams, Mina Loy, Marianne Moore and T.S. Eliot. Prior scholarship on the poets minimizes the effect of the grotesque in favor of the more objective elements found in such movements as Imagism. This text argues that these poets re-established the grotesque in their writing after World War I mainly through Hellenic myths, especially myths concerning the motif of the tree. The myths of Daphne and Apollo, Baucis and Philemon, and others use the tree motif as an example of complete metamorphosis into a new identity. -

VHSL Regular Season Round #1

VHSL Regular Season Round 16 First Period, Fifteen Tossups 1. Fluid movement across these entities is calculated by the Starling equation. In the kidney, the glomerulus is formed of these entities, whose activity was first observed by Marcello Malphigi. A "fenestrated" type of these allows small amounts of protein and small molecules to diffuse through it. Many of these structures are only one cell thick. Oxygen is delivered to cells by diffusing across the walls of these vessels. For 10 points, name these smallest blood vessels in the human body. ANSWER: capillaries [or capillary; or capillary bed before mentioned] 032-09-2-01101 2. This President was nicknamed "Ice Veins" because of his cold personality. This man helped settle a boundary dispute between Great Britain and Venezuela. One controversial bill signed by this President gave disability pensions to veterans even if their injury was not from combat. This man worked with the "Billion Dollar Congress" and signed the Sherman Anti-Trust Act, the Sherman Silver Purchase Act, and the McKinley Tariff. For 10 points, name this President, the grandson of William Henry Harrison. ANSWER: Benjamin Harrison [prompt on Harrison] 021-09-2-01102 3. These particles can undergo an inelastic scattering process described by the Klein-Nishina formula; that process consists of them losing energy when they collide with matter due to Compton Scattering. When one of these particles imparts enough energy to an electron for it to exceed the work function, that electron may be emitted from the surface of a metal in an effect described in a 1905 Einstein paper. -

Memory of the Nazi Camps in Poland, 1944-1950

Arrested Mourning WARSAW STUDIES IN CONTEMPORARY HISTORY Edited by Dariusz Stola / Machteld Venken VOLUME 2 Zofia Wóycicka Arrested Mourning Memory of the Nazi Camps in Poland, 1944-1950 Translated by Jasper Tilbury Bibliographic Information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data is available in the internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de. This publication is funded by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Poland. Editorial assistance by Jessica Taylor-Kucia. Cover image: A Red Army soldier liberating a camp prisoner (Za Wolność i Lud, 1-15 Apr. 1950). Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Wóycicka, Zofia, author. [Przerwana żałoba. English] Arrested mourning : memory of the Nazi camps in Poland, 1944-1950 / Zofia Wóycicka. pages cm. -- (Warsaw studies in contemporary history; volume 2) Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-3-631-63642-8 1. Collective memory--Poland. 2. World War, 1939-1945--Prisoners and prisons, German. 3. World War, 1939-1945--Concentration camps--Poland. I. Title. HM1027.P7W6813 2013 940.54'7243--dc23 2013037453 ISSN 2195-1187 ISBN 978-3-631-63642-8 (Print) E-ISBN 978-3-653-03883-5 (E-Book) DOI 10.3726/978-3-653-03883-5 Open Access: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial No Derivatives 4.0 unported license. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ © Zofia Wóycicka, 2013 Peter Lang – Frankfurt am Main · Bern · Bruxelles · New York · Oxford · Warszawa · Wien This book is part of the Peter Lang Edition list and was peer reviewed prior to publication. -

Colonia Tournament Round #1

Colonia Tournament Round 1 First Period, 20 Tossups 1. This artist's portrait of Pope Innocent the Tenth was modified by the modern painter Francis Bacon. This artist painted the god Bacchus crowning a drunken reveler with laurels in his work Los borrachos. This man painted himself holding a palette and wearing a black robe with a cross on it in his another painting. That painting by this man also depicts a girl stepping on a dog, and a dwarf attending to the Infanta Margarita. For 10 points, name this court painter to Philip IV who painted Maids of Honor in his Las Meninas. ANSWER: Diego Velazquez 015-10-14-01101 2. This element forms cluster compounds with iron, and those cluster compounds are important to enzymes like coenzyme Q-cytochrome c reductase (CO-EN-zime "Q" SY-toe-krome "C" ree-DUCK-tase). Bonds between two of this element, which form between cysteine (SIS-teen) residues, are critical to protein conformation. This element has an isotope that forms an eight-atom ring. For 10 points, name this element associated with the smell of rotten eggs, with atomic number sixteen. ANSWER: sulfur 022-10-14-01102 3. This man was the victorious commander at a battle that saw the bribing of the grain outpost commander at Clastidium and in which his half-brother Mago opened with an ambush. In addition to defeating Tiberius Sempronius Longus at Trebia, this man ambushed Gaius Flaminius and drove Roman forces into Lake Trasimene. This man's brother's head was thrown into his camp at one point. -

Occultism in Western Theater and Drama

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Studies in Romance Languages Series University Press of Kentucky 2005 Stages of Evil: Occultism in Western Theater and Drama Robert Lima Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/srls_book Part of the Dramatic Literature, Criticism and Theory Commons, English Language and Literature Commons, and the Modern Literature Commons Stages of Evil Studies in Romance Languages: 49 John E. Keller, Editor Occultism in Western Theater and Drama ROBERT LIMA THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY Publication of this volume was made possible in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Copyright © 2005 by The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved. Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008 www.kentuckypress.com 09 08 07 06 05 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lima, Robert. Stages of evil : occultism in Western theater and drama / Robert Lima. -

Shadows of the Past by Michael Baumann

SHADOWS OF THE PAST SHADOWS OF THE PAST A STORMBRINGER 5th EDITION ADVENTURE BY MICHAEL BAUMANN & MATTHEW HARTLEY The following adventure is designed for four to six moderately experienced Stormbringer characters, but Game Master's the adventure is easily increased in difficulty by adjusting the skill level and/or number of NPC Synopsis opponents. With a bit of work it can be modified for the Corum or Hawkmoon games as well. If the party is extremely skilled, has several bound demons, This adventure takes place after the events in The contrivances, or technological devices the Game Sands of Time. An alternate beginning is presented Master will have to radically redesign the opposition. for those Game Masters who choose to run this Information to be read to the players is always in scenario on its own. Italics while GM information is in plain type. The adventure begins as the characters awaken This adventure catapults the party to the Shadow on the Broken Plains of the Shadow Plane. Their Plane. This horrid place lies close to the plane of The unconscious selves are about to become the dinner Young Kingdoms. Moorcock's writings indicate that it for a band of roaming demons. Undoubtedly, they is a place of banishment for those who offend the will object to this and a fight will ensue. Once the Lords of the Higher Worlds. While it is easy to get to demons have been beaten off they will find a ginger- the Shadow Plane, leaving is an altogether different bearded dwarf inside a sack carried by one of the matter.